This is what the Defector staff enjoyed reading in 2020.

Such a Fun Age, by Kiley Reid

It's hard to recommend a book for a year like this. What do you recommend to a friend who can't stop looking at their phone (me)? What do you recommend to someone depressed over the state of the country (everyone)? How do you even focus for long enough to read a whole-ass book instead of just zoning out in your little cocoon of sadness and fear? All year I have pointed to Kiley Reid's debut novel, Such a Fun Age. The opening two chapters are enticing in exactly the way good gossip used to be: alluding to a bigger issue, but not exactly telling you what happened. The novel tells the story of Emira Tucker, a young black nanny living in Philadelphia who works for a white woman named Alix Chamberlain. The book opens with Emira taking Alix's young daughter to the grocery store to get her out of the house at Alix's request and promptly being accused (because she is young and black and dressed for the party she just came from) of kidnapping this white child.

At its heart, the book is a story about transactional relationships, about white privilege, about trying to figure out who you are at 25 years old, and about how our past never really leaves us. - Kelsey McKinney

Vernon Subutex 1 and Vernon Subutex 2, by Virginie Despentes

I went into 2020 with the goal of reading 50 books. I haven’t read that much since college, and since I was unemployed at the start of the year, I figured I’d put my free time to good use. Then the pandemic happened, and my desire to do anything but stay in bed and quietly moan at the misery of the world around me won out. However, before quarantine kicked in, I did manage to read 10 books. The best of those books, and one-half of the best thing I read in 2020, was Vernon Subutex 1, a novel written by French author Virginie Despentes.

Set in present-day Paris and following its titular protagonist and a large cast of supporting characters, Vernon Subutex 1 has a flimsy main plot driving the action: Alex Bleach, a famous rock star who dies of an overdose at the start of the book, left behind tapes of self-recorded interview monologues with Subutex, who is thrown onto the streets of the city after his rent payments stop clearing. There is a hunt for both the man and the tapes, colored with Despentes’s open disdain for French society, a disdain best exhibited by the point-of-view characters she writes. There is a lecherous producer, a hard-right fascist who everyone tolerates, a caricature of an academic liberal ... the whole nine. The books might be fictional narratives, but the real juice comes from the absurd social commentary on French culture, the government, and capitalism as a failed entity.

The second book in the trilogy—the third has not been translated to English yet, and my brain is too weak these days to dust off my French—sees the group of characters find Subutex and, somehow, turn him into their homeless messiah. It’s a wild plot shift, but an increased focus on Bleach and more of the commentary and humor turns the second novel into a better work. Without spoiling much, I will say that it left me waiting for that translation of the third book, because the first two were the most engaging reads I had this year, a year that started off so promisingly for my reading habits but turned into a slog when I wasn’t zooming along the literary streets of Paris, with all of its profane warts and blemishes on full display. - Luis Paez-Pumar

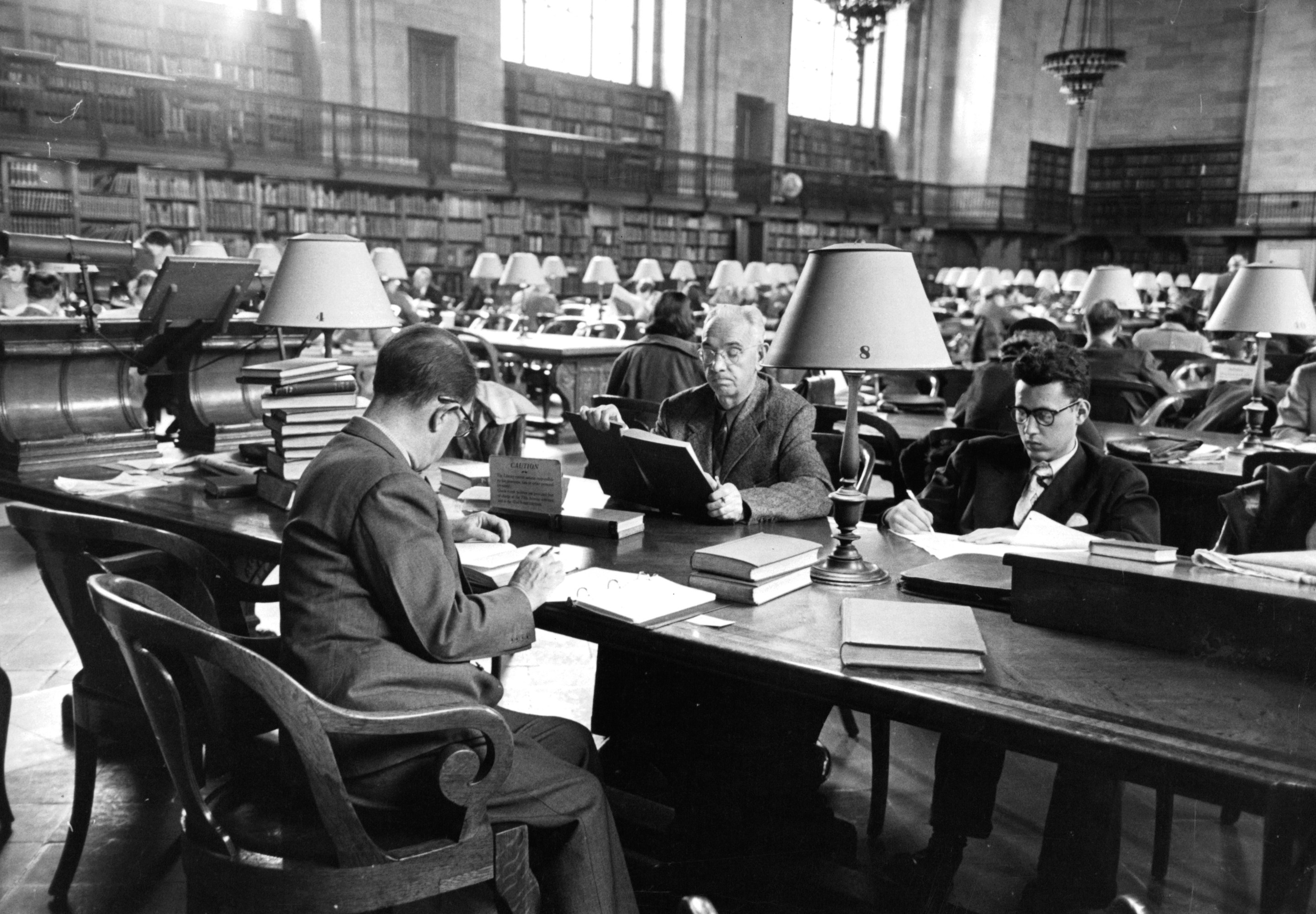

Cuyahoga, by Pete Beatty

Recently our own Barry Petchesky noted that he’d read 115 books during 2020, which is the sort of claim that would be frankly implausible if you were not familiar with Barry’s whole thing. There has been no year in which I’ve approached that number—which is fine, as attempting to live any facet of Barry’s lifestyle would surely destroy me—but lord knows this was about as far off as I’ve ever been. The spaces and times in which I’ve read most happily as an adult were, from the end of February to now, more or less all suddenly and irrevocably off-limits. The places I am happiest reading are on a moving train, or in a quiet hour alone, or in a clearly delineated mental space of “vacation/not-working.” I have not had those, and so I have not really been able to read as much as I would like, or to retain even the dwindling amounts of what I read that my deteriorating brain has permitted me in less-afflicted years past.

But I can tell you where I was when I finished reading Pete Beatty’s novel, Cuyahoga, which is a good sign. This was the weekend after Election Day, and we were in a hotel room in Kingston, New York when we were not outside of it, driving around to various places or stubbornly going on overdetermined walks in 48-degree weather, and in every moment that I could justify it I was reaching for the book. I should say here that Pete is a friend and former work associate of mine, although I haven’t seen him in years, and I have always thought he was an excellent writer; that he wrote a novel at all made me happy, and that it was so wild and wonderful and singular made me happier still. (As it happens, this was the second time this year I had that experience; Eric Nusbaum’s Stealing Home was the other book I considered for this entry.) I knew very well that Pete could write, and I suspected strongly that I would enjoy whatever he wrote. I was still not expecting Cuyahoga.

The book is a fable set in Ohio, during the hazy mythic American prehistory known as “the Martin Van Buren administration,” amid the vague and vicious rivalry between the nascent cities of Cleveland and Ohio City, and centering upon the feats of Big Son, a strapping “American Hercules” who clearcuts whole forests in a single night but struggles to make a living or get the mortals around him to take him seriously. The story is told, in colorful old-timey vernacular language that quickly becomes jarringly easy to read, by Big Son’s younger and less outwardly notable brother, Medium. There are ups and downs and betrayals and upstagings and turns-about and a few disasters of varying sizes; the ending is, in its way, decently biblical. I do not want to give too much away, but I will say that it is not like anything else I’ve ever read, and that it’s astonishing to think that any of it could have come from the brain of someone I once heard say the name “Jacquizz Rodgers” out loud in a bar. All of it is astonishing.

When I have missed books this year, a lot of what I’ve missed has been about the spaces in my life that books have traditionally occupied. They’re things I take with me when I go places, or that I enjoy when I am elsewhere, or that I fit into the little fissures of leisure time that open in the day when and where they appear. I have not had those this year, and can attest that life unfolding as a clear flat pasture of unbroken anxiety under lowering skies absolutely sucks ass. For everything that I loved about Cuyahoga, for how it surprised and delighted and entertained me, the thing I appreciate most in retrospect was how it somehow cleared all that away and made its own space. It fits Big Son, and the whole strutting/stumbling legend at the center of the story, and the bigger enterprise Pete took on. It blew a hole in the heavy everyday and made its own space. - David Roth

Villette, by Charlotte Brontë

Interior fiction is meant to dissolve the space between reader and character, but in Villette, our narrator becomes increasingly a riddle. She is Lucy Snowe, orphaned by some unspoken tragedy and compelled, for no particular reason, to leave England for continental Europe, where she stumbles into work as an English teacher at a pensionnat. I found her strange, mean, and curiously withholding. She complains about everyone in her company, misses no occasion to badmouth Catholics, and at one point, locks a student in a closet. Readers directly experience her callousness, too. The first plot twist of Villette is bested immediately by a second: that Lucy has known the details of the first twist for quite some time but hadn’t bothered to tell us. How rude! How vexing! And still! She inspires our affection. Beneath the caginess, Lucy craves companionship and approval. Forbidding that, she just wants to make peace with her solitude. Who can’t relate? This book about loneliness by a great chronicler of lonely women brought me real comfort in the loneliest year of my life. - Maitreyi Anantharaman

The Small Bow

I basically lost the ability to read books this year. I don't really feel like explaining how or why this happened, but it did.

What I did read a lot of, though, was The Small Bow, a newsletter about being in recovery written by A.J. Daulerio. Each weekly issue shows up in my email inbox overnight, and I cherish the mornings on which I can roll over, light up my phone, and spend the first 15 minutes of the day reading The Small Bow, which feels like putting my brain in a warm bath, instead of scrolling through Twitter, which feels like putting my brain in a microwave.

It seems counterintuitive to say that a newsletter about this specific topic would have such a calming effect on me, but I always find myself feeling a little more centered after each reading. That's because Daulerio, while not being afraid to bring up heavier topics, never leans on salaciousness for its own sake. Instead, he crafts each issue with grace, good humor, and hefty levels of self-reflection, slipping little lessons about how to live a better life into each story he tells.

This isn't a newsletter for rubberneckers or people looking to get scared straight, but for people who want to see what it looks like to better understand one's own mind, to keep pushing through it, and to work every day to create a more peaceful existence. What could have been more useful than that in a year like this one? - Tom Ley

We Both Laughed In Pleasure, by Lou Sullivan

In We Both Laughed In Pleasure, a collection of diaries from 1961 to 1991 by Lou Sullivan, a gay trans man who often gets tagged with stifling and dull labels like “pioneer,” the author emerges as a brilliant, sexy, funny, and soulful presence within a community that subtly becomes larger and larger over the course of his too-short life. Sullivan’s writings—which he was arranging for publication late in his life—became a kind of cult hit in with this release three decades later in 2019, and, as you can tell if you get the gist of these posts, they were the best thing I read in 2020.

Across 30 years, We Both Laughed In Pleasure gives you a first-person tour through Sullivan’s Beatles-obsessed boyhood in the early 1960s Midwest all the way through his '80s activist endeavors and fights with doctors and growing kinship with other people like him in and around San Francisco. His private scribblings are far more charismatic than anyone’s unedited work has a right to be, alternating back and forth on multiple occasions from gossipy and boy-crazy to thoughtful and inspiring. Lou is so lovable, so overflowing with feeling, that there’s real joy in reading him excitedly describe hook-ups and real pain in reading the entries in which he’s venting about the medical establishment that refuses to comprehend him.

“I’ve tried to learn to live without affection, but I can feel it eating me from inside,” reads perhaps my favorite passage. “It seems so foreign to me when I see how free + open everyone around me is with their bodies. I realize that I don’t even give potential lovers a second glance, or encourage even the slightest any men who are attracted to me. And I know they are. I am beautiful! It hurts me too much to encourage them, or to even notice their attentions to me. I can’t stand to see someone offering themselves, and my having to deal with this fucking body. It’s just not fair. I have to start now to pursue the rest of me.”

But in just the last few pages, it’s all wiped away by AIDS, the diagnosis of which at age 35 comes as a sudden shock in the diaries even if you already know how they’re going to end. Sullivan remains determined in the final entries: "A big fear of mine is that I will die before the gender professionals acknowledge that someone like me exists," he writes. "And then I really won’t exist to prove them wrong." But eventually it becomes more difficult for him to attend Pride. And then more difficult for him to get out of bed. And then, well, the entries stop.

I think about that loss. And then I multiply it by more than 300,000. It’s a level of devastation to the gay community that, as a member of the PrEP generation, I’ve never quite been able to wrap my head around, though I’ve certainly tried to lately. Lou is one of all these people I love whom I could never meet, who’s sort of canonized in my brain because I can’t even imagine what it was like to live and die in their era. I treasure anything that gets me closer to them. - Lauren Theisen

The Elementals, by Michael McDowell

The best haunted-house story ever written is The Haunting of Hill House. But the tier below that is no slouch, containing stone-cold classics like The Turn of the Screw, The Shining, and House of Leaves. Add to that tier Michael McDowell's The Elementals, the best haunted-house book you've probably never read, and never heard of.

There's a good chance you haven't even heard of McDowell. Born in Alabama, McDowell emerged in the early-'80s horror boom as every bit the equal of a King or a Straub, but with a very particular bailiwick: darkly affectionate portraits of deep-south small towns and the people who populate them; hidden secrets that may or may not be metaphorical; domineering matriarchs jealously protecting their people; the power of the very earth and water being instruments, and sometimes operators, of revenge. All of these mesh to best effect in The Elementals, which sees two intermarried clans retreat to their two identical Victorian vacation homes on the Gulf shore, on a remote beach that becomes an island at high tide. There used to be three houses, you see, but one is slowly and inexorably being consumed by the beach itself.

What you have here is a classic, meat-and-potatoes ghost story, with the horror steadily ramping up and never yielding, not even when the action briefly returns to the mainland. But it's the interplay among the characters that provides the seasoning to make this an all-time great. This is a family of big personalities, from the alcoholic "Big Barbara" McCray, who the family has brought to the beach in the hopes of drying out, to relentlessly curious teenage girl India, self-sufficient from more or less raising herself in New York, but wholly unprepared for the entity that lies waiting inside the third house. McDowell clearly has great affection for the people and the corner of the country in which he grew up, and his portrayal never flirts with caricature. He does not romanticize the south, as so much southern gothic literature does, nor does he hold it in disdain. His writing is the real star here, one moment capturing mounting dread, the next breaking the tension with a laugh-out-loud exchange, the next offering an achingly beautiful description of the moon over the waters.

When the horror-fiction boom overfed and imploded, McDowell dabbled in other genres, sometimes under other names, and, delightfully, wrote the screenplays for Beetlejuice and The Nightmare Before Christmas. He worked ever more sparingly as he battled AIDS before dying in 1999. Most of his books fell out of print, the sands of time swallowing his work before an overdue rediscovery and reappraisal in the last few years. (It's no accident that I'm choosing a 1981 book for the best thing I read in 2020.) That he was an unabashedly prolific writer of genre fiction was held against him, though he never felt shame over it, or understood why anyone thought he was supposed to. "I am a commercial writer and I'm proud of that," McDowell told an interviewer. "I am writing things to be put in the bookstore next month." Implicit in that statement is a condemnation of any snobbishness that penalizes fiction for being entertainment. A book written to be sold is, when you get right down to it, a book written to be read. - Barry Petchesky

Essential Essays, by Adrienne Rich and The Puttermesser Papers, by Cynthia Ozick

In 2020, with nowhere to go, I decided to finally set about all the books in my to-read pile. If you've already read Adrienne Rich's Essential Essays or Cynthia Ozick's The Puttermesser Papers, please skip ahead. I would love to not waste your time. If you haven't, these are two books that, though years apart, felt meaningful for me in years of suffering, triumph, and then more suffering.

The very first essay in Rich's collection is a declaration of transformation. From 1971, it's about the rise of women poets claiming their own place alongside men, but you also could say it's about every space in which women have dared to demand more than their allowance. "To the eyes of the feminist, the work of the Western male poets now writing reveals a deep, fatalistic pessimist as to the possibilities of change, whether societal or personal, along with a familiar and threadbare use of women (and nature) as redemptive on the one hand, threatening on the other; and a new tide of phallocentric sadism and over-woman hating which matches the sexual brutality of recent films." This is happening, she writes, because "the creative energy of patriarchy is fast running out; what remains is the self-generating energy for destruction."

From there, the collection spans Rich's work over more than 40 years. I'm choosing to focus on two essays early in the collection, each arguing for a woman writer's place in the canon: Charlotte Bronte's Jane Eyre and the poetry of Emily Dickinson. In each, Rich's analysis pulls from the writers' own work as well as history to make the case that these women's contributions have not just merit, but are key pieces of literature and creative history. Reading them from the light of 2020, I was struck by both the forcefulness of Rich's words and also how effective they were. I read them now as a person who had always assumed the greatness of Bronte and Dickinson, naive to the idea that anyone ever had to fight for them. Rich is no optimist; she sees all the hatred and ugliness in the world. But she demands that women work for change and shows we can achieve it.

Except our battles rarely follow a straight line. In The Puttermesser Papers, Ozick examines just one life, and one that's quite ordinary: Ruth Puttermesser, a person so plain her last name is Yiddish for butterknife.

Ozick declares to her reader there will be no use of Puttermesser as a commodity here. Instead, she tells you, "Puttermesser is not to be examined as an artifact but as an essence. Who made her? No one cares."

Ozick openly flouts the given conventions of modern storytelling. It's called The Puttermesser Papers because the book is five snippets from Puttermesser's life. The gaps are not explained. When Puttermesser is seemingly set up at a chance for love early on, Ozick says in blunt language that will not happen because "the difficulty with Puttermesser is that she is loyal to certain environments." The most beautiful flourishes in the book are reserved for describing the mundane. Here's Ozick on institutions: "The early fits of innovation subsided and gradually the old way of doing things crept back, covering everything over, like grass, as if the building and its workers were together some inexorable vegetable organism with its own laws of substance."

And yet Puttermesser's life does contain flashes of excitement. She builds a golem who makes her mayor of New York City (it does not end well). She falls in love with a man who makes a living copying the artwork of others (it also does not end well). She tries to rescue a cousin from the Soviet Union (who did not need rescuing). Puttermesser, our modern woman, has heard the clarion call of Rich demanding we fight for change. But it never seems to quite work out for her, and that's OK. Ozick is brimming with dazzling love for her all across the page. But love doesn't guarantee you a happy ending.

It can be hard to see, from the morass of everyday survival, that much of our lives are decided by the choices made by those who came before us. Someone decided that this book or that book is one of the greats. Someone decided that women can do this but cannot do that. Someone decided that public health didn't need funding. In our daily lives, they can add up to a kaleidoscopic jumble, like Puttermesser. Take a longer view, and you can see the forward march of change, like Rich. I have, at various points this year, felt sympathetic to both points of view, depending on the day and the daily news. Together, they feel like a summation of 2020, partly mired in muck, somewhat gazing toward a better future, fighting for a way to get there, and unclear how it all will end. - Diana Moskovitz

The Tiger, by John Vaillant

The Tiger was not published this year, but whatever. It’s about a man-eating Amur Tiger than went on a rampage in the Far East of Russia in the 1990s. I have never been to the Far East of Russia. It’s one of those places on the map I stared at when I was a kid, wondering what it could possibly look like. Thanks to Vaillant, I now feel like I’ve been there. That’s no small gift when you can’t travel anywhere at all. I also learned enough about tigers to have my skull blown: how they think, how they hunt, how they wait, and how they used to peacefully co-exist alongside mankind before mankind decided it wouldn’t peacefully co-exist with anything at all. - Drew Magary

The Yellow House, by Sarah Broom

My friend asked, “What do you think The Yellow House is about?” Like some kid who hadn’t made it past the first three chapters and was in the terrifying spotlight of a book report, I said, “Well, I feel like it’s about family.” So, that was reductive. It’s not wrong, it’s just not fully right, either.

Sarah Broom’s memoir is a lot of things: a story of knowing your roots, an interrogation of the failures that left New Orleans gutted by Hurricane Katrina, a travelogue, a history of the black diaspora within America. And yes, it’s about family. Broom is the youngest of a dozen siblings, she came along when most of her brothers and sisters were far older than her, only to have her father die when she was six months old.

So The Yellow House is a book that contains volumes of life, framed through the experience of one family’s shotgun-style home in New Orleans East. I wasn’t expecting The Yellow House to make me crumple the way it did. It got into my tender and neglected spots, the ones where the connections to your people and the memories you think you know becomes less vague over time. It felt too similar to when I read Angela Flournoy’s The Turner House, a novel that hit me hard enough to make me put the book down and take a break from reading at times.

What my friend wanted me to reflect on was that The Yellow House wasn’t just about family, but about a place, and all those routes and buildings and faces and sensations that are collected in making you. Like I said, it contains volumes. I’m grateful for all of it. - Justin Ellis

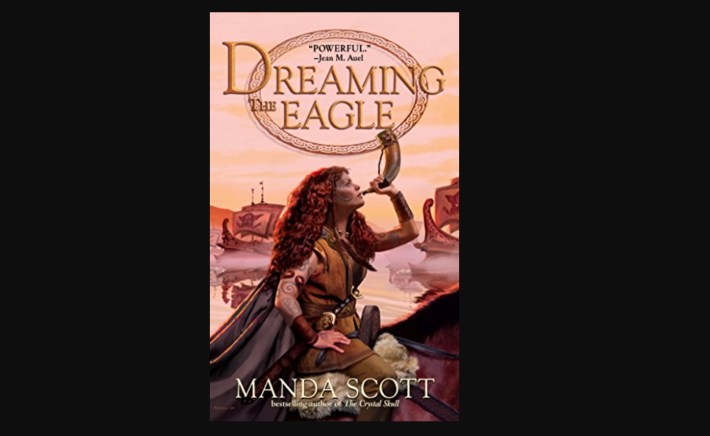

Boudica, by Manda Scott

The best book I read in 2020 was four books, a tetralogy of witchy historical fiction novels about the Celtic warrior Queen Boudica and her ultimately futile resistance to Roman invasion and occupation two-thousand years ago. I don’t think the series ever got much mainstream traction, though a copy of the first book was one of the most sought-after books in the small library of the farm at which I spent most of the first three months of the year. People would take turns reading Boudica on goat walks or sitting around the garden, though since we only had the first one, pursuing the sequels meant you had to look in the outside world. It is important for context that you know the cover of the first one looks like this.

Scottish author Manda Scott suffuses the historical record with a rich layer of Earth-based Celtic magic, largely through an analogous class of seers based on the Druids. The shit rocks, and if you can, trust me that first half of the first book—where the characters’ conflict-free existence is unspooled in painstaking detail and you learn more than you ever need to know about horse genetics—serves as emotional ballast for the events of the inevitable invasion. I think someone is making a vaguely prestige TV show about the Roman invasion of Britannia but I haven’t watched it. - Patrick Redford