Elementary school ends, and the Harlem kid heads right to the candy store. The baseball cards are out. The kid opens a pack of Topps, is greeted by the intoxicating aroma of cardboard and gum. (Yes, he eats the gum.) Flipping through, everything stops. He’s stunned by the drawings, a breathtaking departure from the normal, staid shots. These cards move him. It’s 1952.

“Years go by, and then I’m into the field,” Dick Perez recalled nearly 70 years later. “And I said, 'Why not bring that thing that excited me? Why not bring that back?'”

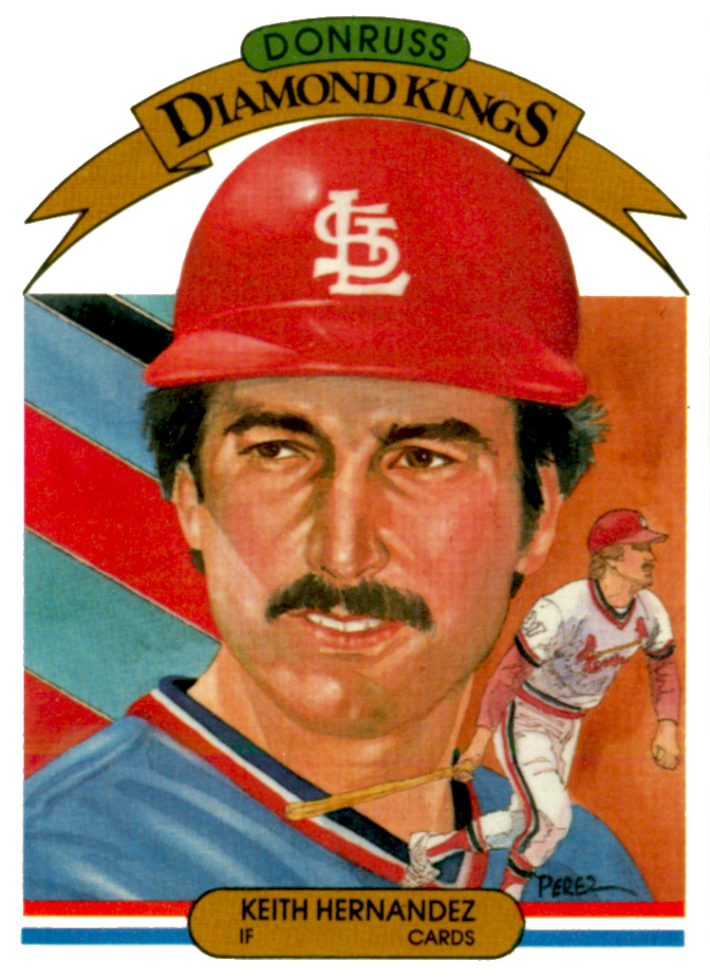

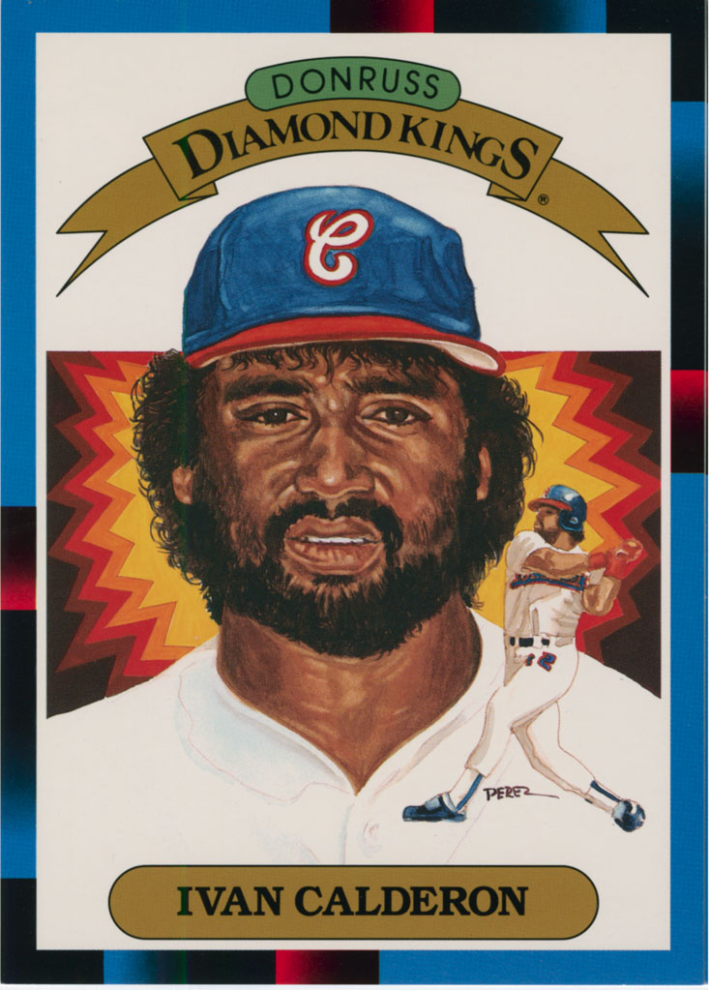

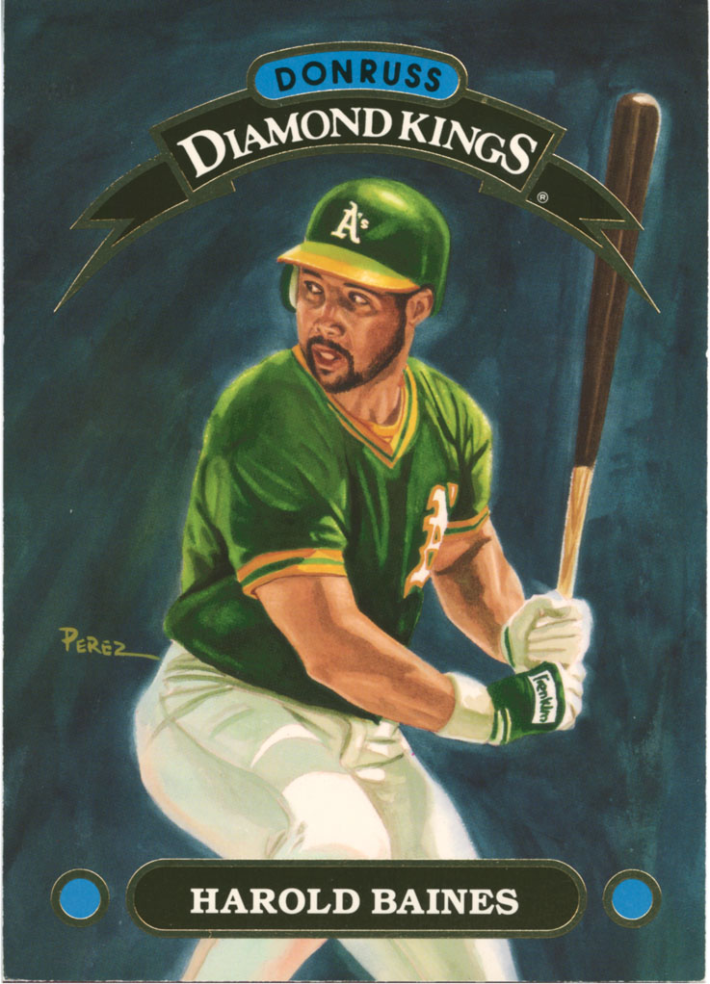

From 1982 to 1996, Perez painted an astounding 400 ballplayer portraits for Donruss’s Diamond Kings subset. Those cards, evocative watercolor portraits of ballplayers hand-picked by Perez and his longtime friend and business partner, Frank Steele, glowed among the posed shots of weary men with frozen smiles or standard game action pics that made up the rest of those sets, and every other set of the era. The cards balanced an unusual visual grandness with the randomness that defines the experience of opening a pack of cards. Yes, you might get a superstar, but also every team was represented in the set, and not every team had a superstar, and Perez hated to repeat himself. And so you might pull a luminous and stylized portrait of, say, Ivan Calderon or Glenn Hubbard. During a time when sports coverage was largely limited to a fan’s part of the country and the odd national game, Diamond Kings elevated unfamiliar players and recognizable all-stars alike to something very much like art.

Those cards could only have existed at that moment in the industry, when a number of new companies were trying new things—not always wisely, or well—in what had become a staid business. At a moment in the trading card business defined by a headlong glut of tossed-off cards, Perez and Donruss somehow managed to make something memorable.

“There’s always some guy who’s the bridge between the old and the new,” says illustrator Tom La Padula, “That’s an argument you can have over a lot of beers. But he was. Perez was that bridge.”

In 1980, Fleer, a struggling card manufacturer, won an antitrust suit against Topps. For years, Topps had been the only player in the industry. With that ruling, the field for baseball cards was wide open.

Back then, Bill Madden, the longtime baseball columnist for the New York Daily News, wrote a baseball cards column for The Sporting News. He recognized that the ruling was huge and called Marvin Miller, the longtime executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association, who died in 2012. Here’s how Madden remembers the conversation:

“We’re giving out our first license in a few weeks,” Miller said.

“That’s for Fleer, right?

“No, it’s for Donruss.”

“Donruss? What is that?”

Donruss was a subsidiary of General Mills. It did have experience in non-sports cards and decided to get into the baseball card game after the Fleer ruling. “We figured that if anybody should be involved, it ought to be us,” Donruss president Stewart Lyman told the Memphis Press-Scimitar in March 1981. After all, he told the Cincinnati Enquirer in February 1981, the company knew about the business.

Madden had no idea. He called Lyman, who died in July 2022. Madden introduced himself, explained his column and asked his first question, which was, “Who are you?”

The executive laughed. “‘We’re just a little confectionary business down here in Memphis, Tennessee,’” Madden recalls Lyman saying. “‘I have to be honest with you: We know nothing about baseball cards and we know nothing about baseball.’”

“I guess this is a perfect marriage,” Madden joked, “because nobody knows anything about you either.”

“We need help down here,” Lyman said. “Do you know anybody who might be able to do the bios and the stats?”

“Yeah, you’re talking to him,” Madden said.

Soon, Madden was pounding out bio sheets on a typewriter, filling out stats in pencil on the bottom. “I almost had a nervous breakdown,” he says. ”I had to do 660 of these things. It was primitive as primitive could be—and those cards looked it, too.”

Donruss needed something to differentiate itself from the packs. Perez, who had become one of baseball’s premier artists thanks to his art postcards portraying members of the Baseball Hall of Fame, would become the answer.

Perez’s Hall of Fame gig came through an attorney and baseball memorabilia collector named Frank Steele, whom Perez met through a mutual acquaintance. Steele was a member of the New York Stock Exchange. He knew people. To succeed as an artist, Perez says, requires a good amount of luck. A patron helps, too, and Steele, who became his friend and mentor, filled that role. The pair opened a gallery in 1979 with the intention of selling the kind of classic cards they adored, and Steele became a relentless advocate for the younger artist. He was the perfect partner for the mellower Perez—passionate, savvy, and relentless.

“Dick’s work certainly spoke for itself,” says Vince Nauss, the longtime Philadelphia Phillies publicity director who worked with Perez in Philadelphia and later at Donruss. “Frank would be more, ‘How can we utilize Dick’s talent more?” The arrangement was simple, Nauss said. Steele would present the idea, and then Perez would excel at it “like no one I had ever known.”

“Dick was not someone who hung around the ballparks and necessarily knew his subjects,” Nauss adds. “It was an inherent, God-given talent that he had that he could capture the person.“

Steele worked out the deal for the Hall of Fame postcards and, Madden said, broached the idea of getting Perez to do cards for Donruss. Madden, who loved the Steele-Perez Hall of Fame postcards—he bought the sets and three of Perez’s original paintings—was game. Madden proposed an annual art subset and Donruss accepted; Perez, in a sense, was now free to return to the candy store.

Baseball cards in the 1980s were undistinguished, says Dave Jamieson, who wrote the fantastic history of the baseball card business, Mint Condition. Specialty cards—league leaders, record-breakers—were always a part of sets, but always bland. The business of making baseball cards was more or less just that; no one was trying too hard. “The Diamond Kings cards felt like a treat in the way that those other specialty cards did not generally,” he says.

They were, says baseball card industry veteran Tracy Hackler, mesmerizing works of art. This sort of thing is subjective, but that assessment is not hyperbole. Illustrator La Padula sees the influence of fine art on Perez’s work. Artists such as Joaquin Sorolla and 17th-century Spanish master Diego Velázquez used skin tones to bring striking and unusual realism to their portraiture; Perez, La Padula says, “gets this really great electric color where maybe the cheek tones are a little too red or the chin is a little too gray because the guy didn’t shave that day.”

Cable wasn’t yet a household commodity; the Internet was years away from being even a curiosity. Cards offered a chance to meet unfamiliar ballplayers only known from box scores or maybe This Week in Baseball. “I had never seen something like that,” says the illustrator Cuyler Smith, who collected cards in the early 1990s, and is known for his pop culture trading card homages. “They were actually my favorite cards to collect, due to having these players that I love so much just being represented in a different way, something that was unique from just a photo or an image.”

As new competitors popped up during the beginning of the baseball card boom, Donruss offered something no other manufacturer could provide—the chance to open a pack and find something so different. “It’s like something no one ever did before,” La Padula says. “We talked about Topps having that monopoly. Now, all of a sudden, Topps looks like Grandpa. Who wants Grandpa? You want the new, hip thing.”

The hip, new thing embedded into the sensibilities of current and future artists. Andrew Farago, curator of the Cartoon Art Museum in San Francisco, saw Perez’s impact on the covers for Beckett’s monthly price guides. “Both of those combined inspired maybe millions of high school art projects as kids drew their own renditions of Mike Schmidt and Kirby Puckett and Ken Griffey, Jr,” he says. Smith remembered spending hours replicating a Frank Thomas Diamond King in his youth, trying to figure out Perez’s tricks. The illustrator Andrew DeGraff marveled at the playfulness of the Diamond Kings as a kid, and says he learned from them, too. A background could “be anything. Just take the colors and remix the colors of the palette, to create a geometric (pattern), and it looks great.”

Perez and Steele enjoyed total creative control, including choosing the players that Perez would paint. (Madden says he selected players as well.) “Donruss knew nothing about baseball,” Perez says, and he made the most of the freedom that afforded him. He experimented with colors. He went abstract. He included a tiny in-set painting of a player in action to accompany the portrait. Some approaches flopped, he admits, but the work was indisputably his.

Normal bored Perez—he didn’t want his work to resemble a photograph, and went so far as to combine elements from different photos or tweaking a player’s pose to get the look he wanted. The artist drew inspiration from magazines, the pictures taken by Donruss’s team of photographers, and his own library of 400 baseball books. He painted during the season’s home stretch, when the teams’ stars were established. “I’d rather work knowing that those are for sure the guys, rather than draw or paint something and then have to redo it,” Perez says. Using watercolors, which dry quickly, he could complete a Diamond King in a few hours. It was all about reps, he says, and “nothing to do with some God-given anything. It’s just the idea that you just got good at something, and therefore, you just take advantage of it.” In an industry defined, in that moment and throughout its long history, by craven and unapologetic commerce, Perez somehow found himself making his art, his way. For a while, at least.

As the 1990s progressed and the boom market in baseball cards spiked ever higher, Perez found himself souring on Donruss. The realization that the baseball card market was driven by scarcity—the thrill of the chase, of finding something special, but also of finding something rare enough to be valuable—had not yet arrived. Donruss, like its competitors, was dedicated to giving its consumers as much of what they thought they wanted as they possibly could. “I’m doing Ken Griffey, Jr., like, three times,” says Perez, who created other subsets for Donruss, including its annual puzzle portrait. “How many Ken Griffeys does a kid want?”

It happened everywhere. In the 1990s, Jamieson says, there was an overabundance of card companies; they all offered something like the same product, and the market ate it up. “It was just overwhelming for kids and there was no commonality.” Going to a card store, says Nauss, “became like walking down the cereal aisle.”

And there was too much of that variety, says former New York Yankees publicity director and baseball author Marty Appel, who became Topps’ first director of public relations in 1993. “When all the publicity about card shows and values of vintage cards was the talk of the day, what followed was people thinking, ‘Well, I’m going to start hoarding these cards and start paying for my kid’s college education someday,’’’ Appel says. Customers bought cards non-stop but “the companies were meeting demand by producing so much product” that none would approach the value of past cards. In a market in which scarcity drives value, overabundance somehow became the rule. Then the 1994 strike eliminated games—and promotion. Gravity took over, as it tends to do.

When the baseball card bubble burst, the industry had a choice to make—it could remain a hobby, or reimagine itself as something more like an investment vehicle. As it began its evolution from the former to the latter, Perez made a choice of his own. The 1996 Diamond Kings, his “babies," were his last for Donruss.

Frank Steele died in 2000, at 71. Perez is not in touch with Steele’s widow, Peggy, and declined to say why. (Peggy Steele, who founded an internship program in her and her late husband’s name at The Baseball Hall of Fame, did not respond to an interview request made through a Hall spokesperson.) Perez met legendary ballplayers and frequently left disappointed. “I can tell you stories,” he says, “but I’m not going to do that.” He is happy to discuss the work he did with Donruss, but palpably over baseball card collecting, and collectors.

Baseball, Perez believes, can hold a certain type of adult in its sway, and make their nostalgia curdle into something almost poisonous. These collectors, as he sees it, long for the past, and the sport they loved as a child. And so they spend a fortune on the poetic, the ineffable, only to find themselves further and further from what they seek; in trying to turn their memories into possessions, they cheapen both. At an auction for a Ty Cobb painting he’d done, the runner-up found Perez. “I want you to do an exact piece as the guy who won, but I want it bigger,” the man told the artist. “And I don’t care what you want for it.”

Perez refused to be part of the man’s “vengeance.”

“They talk in terms of, ‘I won your piece,’” Perez says. “You didn’t win my piece, you bought my piece. You paid a lot of money for it. Or ‘I lost.’… And then they use it like a type of stock market. They sell it and buy it and sell it.” At 82, the kid in the candy store is tired of the business. He still does commissions and his own work. He doesn’t have to, “but you can’t not do it.” It’s who he is.

But if Perez’s affection for baseball cards, now in another boom market, has waned, his influence has not. Hackler says that Perez’s art has a very clear legacy and lineage in the contemporary card scene. “There are a lot of modern products,” he says, “straight artistic-inspired sets, that were inspired obviously from the Diamond Kings model.” The card company Panini America, which bought Donruss in 2009, has revived it with Court Kings, Gridiron Kings, and Diamond Kings.

Even today, as the industry experiences robust growth in collecting—and speculation—to rival that of the 1990’s, Hackler says that beauty still matters. “It’s about nostalgia and appealing to your sense of art appreciation, and the way that art accentuates the player,” he said. “There are a lot of categories that dictate a purchase or collecting decision other than money. Diamond Kings is the poster concept for that emotion.”

Perez may have been the bridge between the card business now and its more playful past, but he knows where he stands. The legacy of Diamond Kings, he says, is “incredible.” It was built before kids questioned a card’s investment value or preemptively sheathed it in hard plastic to protect their investment. Actual art created for the most common and craven of commercial reasons—to differentiate a then-struggling card company from its competition—has withstood the volatility of collectors’ whims and lodged itself in the memories of former kids and the work of established artists alike.

Perez gets autograph requests four to five times a week through his website, he says. “I don’t get as (much) feedback or anything from the art postcards as I do with Diamond Kings.”

To view a gallery of all the Diamond Kings cards, visit Dick Perez’s website.