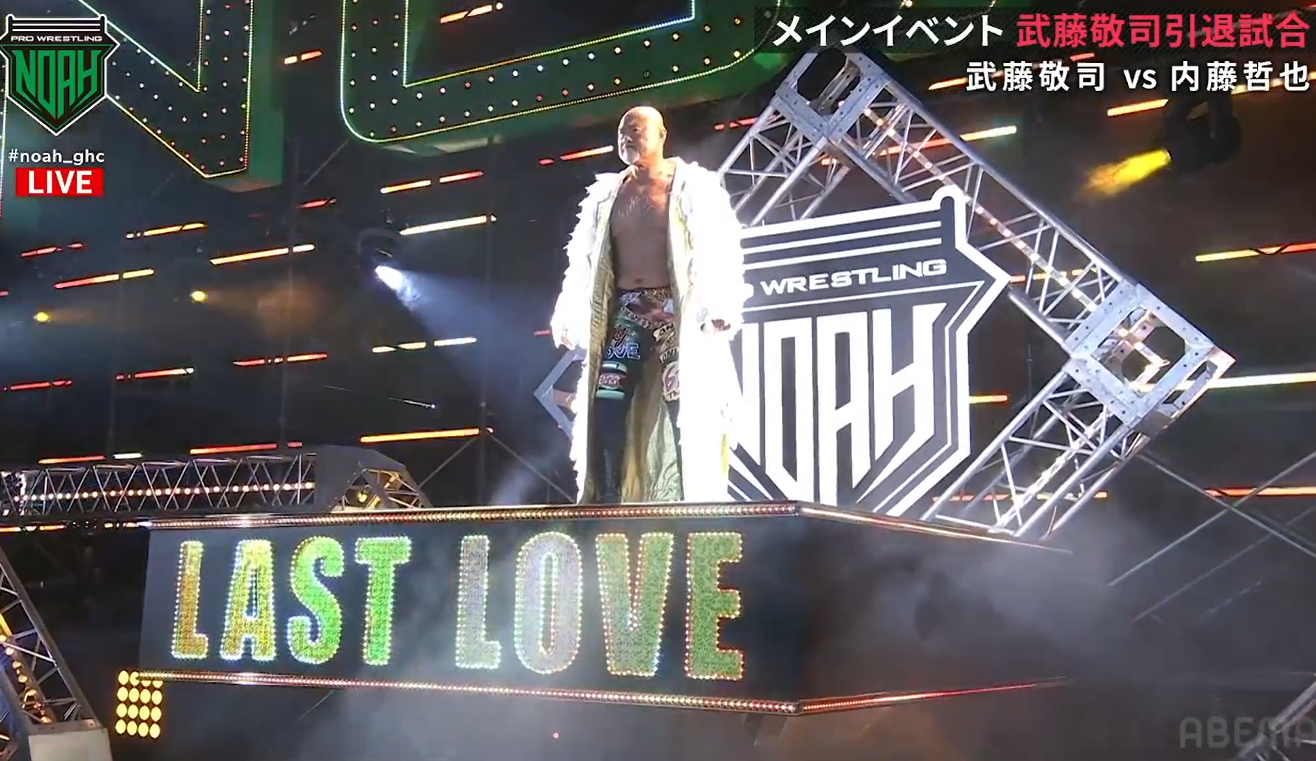

Every retiring legend, not just in wrestling but in pro sports too, deserves a final entrance like the one Keiji Muto got in front of 30,000 fans at the Tokyo Dome on Tuesday. After a three-minute intro of music and lights, Muto ascended through a billow of smoke on a platform decorated with the words "LAST LOVE." The crowd, which can finally cheer again after years of COVID limitations in Japan, serenaded him with his name, and the pyro exploded so ostentatiously that Muto himself was briefly startled as he walked by himself down the endless ramp.

That Muto, the 60-year-old wrestling institution better known to American fans as The Great Muta, was even physically capable of getting into the ring was a victory. This last match, the headliner of an event officially titled "Keiji Muto Grand Final Pro-Wrestling 'Last' Love," was preceded by a lengthy retirement tour that took an even greater toll on a body that long ago already looked too damaged to keep up with modern-day performers. A few weeks ahead of this entrance, following high-profile matches that included such names as Sting, Hiroshi Tanahashi, and Shinsuke Nakamura, Muto was spotted using a wheelchair, and he spoke of injuries to his knee, hip, back, and hamstrings. If this sounds like pro wrestling exaggeration, you haven't seen Muto struggle to move around a ring in his later years.

But whether it was adrenaline or medicine, Muto's final appearance as an active wrestler exceeded expectations and delivered a classic. Though Muto isn't known for being especially selfless in the ring, gaining a reputation in his advanced age for clocking out when the focus wasn't solely on him, this mega-card was filled with a spirit of generosity informed by Muto's lifetime of experience, both beautiful and tragic, in the wrestling business. I came away from this show more appreciative of the history of Japanese wrestling without feeling like its past overshadows its future.

The card itself, though it was held under the Pro Wrestling NOAH banner, was like a potluck, with most notable Japanese promotions showcasing some of their top talent in a stacked undercard. That Tetsuya Naito, one of if not the most popular Japanese wrestler of his own generation, was picked as the opponent for the main event spoke to all the wrestling fans inspired by Muto's work, as Naito idolized Muto when he was growing up. (He kept his trademark stoic cool through the show but I thought I saw glimmers of "I can't believe this is my life.") In the match itself, Muto worked in tributes to Giant Baba, Shinya Hashimoto, and Mitsuharu Misawa—all hugely influential Japanese stars who were denied this kind of curtain call by early deaths. After Naito pinned him, Muto directed a challenge to the announcer's table and took one more loss in a quick, touching impromptu match against his close colleague Masahiro Chono—each man the other's very first and very last professional opponent.

AFTER FALLING TO NAITO, KEIJI MUTO CALLED OUT MASAHIRO CHONO FOR AN IMPROMPTU MATCH!#noah_ghc #MutoFinal pic.twitter.com/BnGipLjN53

— Pro Wrestling NOAH Global (@noahglobal) February 21, 2023

The show had the reverence of a jersey retirement ceremony but also the forward-looking excitement of a home-team blowout that sometimes follows it up. Future stars like Miu Watanabe made indelible impressions, cult favorites like Kento Miyahara shone in front of larger crowds than they're used to, and Japan's biggest in-his-prime star, Kazuchika Okada, showing a hard-ass swagger I can only describe as "Diamondbacks Randy Johnson," looked fresh and motivated as he destroyed the upstart Kaito Kiyomiya right before Muto came on. With a Dome crowd that felt truly unleashed for the first time since before the pandemic, these matches were like a new beginning for a scene that spent the last few years muffled by caution and fear.

Ultimately, for all the spotlight Muto's retirement put on the undercard, this show was always going to be about the man himself. The greatest undercard in history would not have been enough to salvage the embarrassment if Muto arrived barely alive, like Ric Flair in his so-called final match last summer. But even though Muto vs. Naito was subject to some extreme physical limitations, it overdelivered on emotion and storytelling. The match was slow—very slow—but the spectacle carried the quiet parts and magnified the discrete moments of action. Little kicks and bursts of energy that would have been unremarkable in any other match felt enthralling when Muto did them at this time, at this place. But it was something he didn't do, near the end of the match's 29 minutes, that sticks with me. Muto hit one of his signature finishers, the Shining Wizard, but failed to get a three-count with it. He looked up to the heavens, moved Naito into position on the mat, and went to the corner as if he was going to do his other big move, the moonsault. But Muto hesitated, realizing that backflips are a whole other animal at age 60, and Naito capitalized on that hesitation. It was the last bit of offense Muto got in his career.

Seeing Muto's face here, and then watching the kind of moonsault he'd hit when his body still did everything he told it to, is as powerful a dramatization of the aging athlete as I've ever seen. I'm too young to have seen Muto's prime, but as I'm looking down the end of the last sports careers that began when I was a kid—Brady, Federer, Ovechkin, Tiger, Pujols, LeBron—I can understand that feeling of loss when a hero becomes a man. The value of pro wrestling is that it can script these careers—mortal to god to mortal again—for maximum poignancy, but that doesn't make the catharsis counterfeit. It's just an enhanced version of a universal experience.