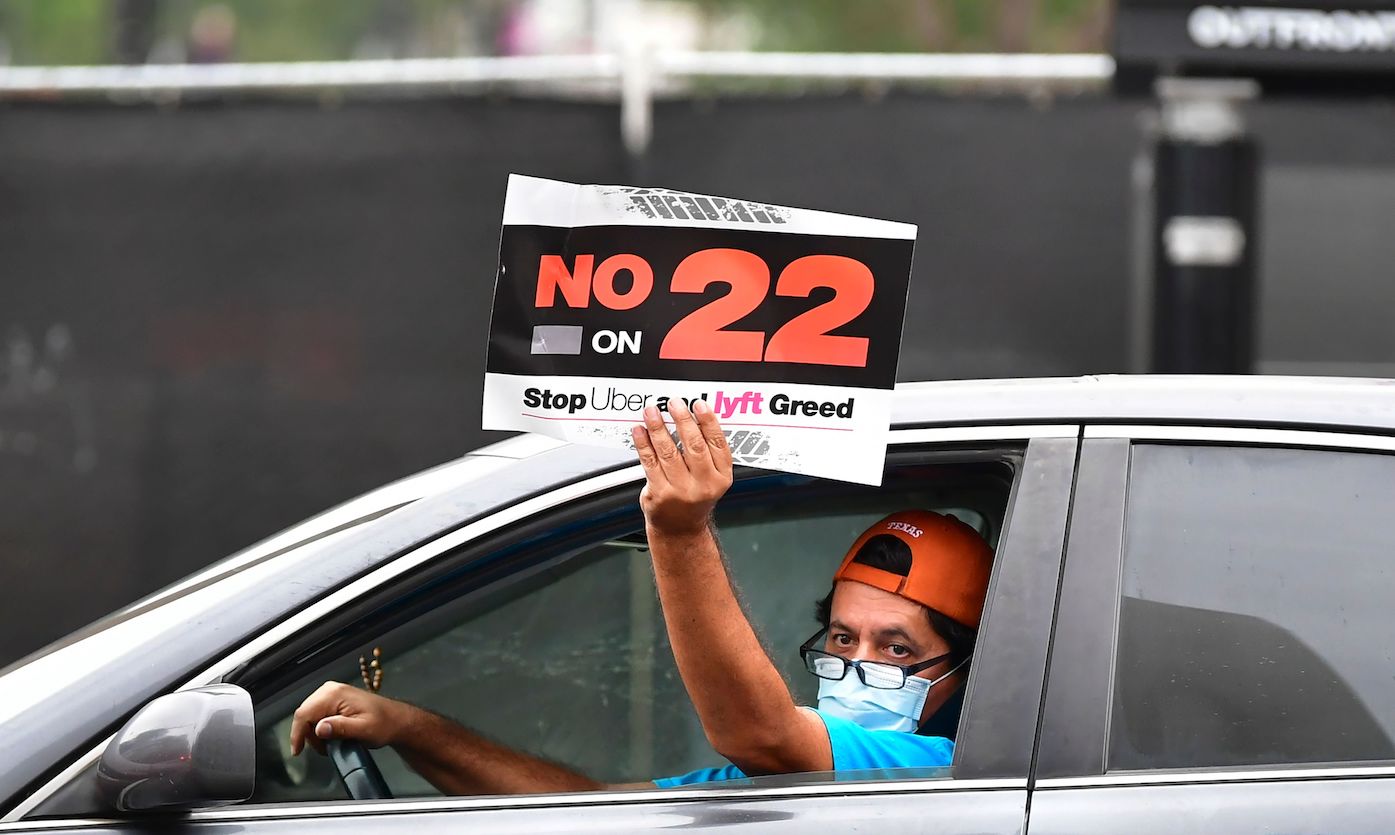

On Tuesday, Californians will vote on 12 state ballot measures. We will have to decide, as a state, whether parolees should vote and how dialysis clinics should operate and whether so-called "gig economy" companies can etch the permanent exploitation of their contract workforce into the law. California's 55 electoral votes are not really in doubt, but the future of labor law very much is.

If you live in the state, you have almost certainly been inundated with messages about the importance of passing Proposition 22. If you open up the Lyft app right now on your phone, you will be greeted by a banner urging you to vote yes on Prop 22 to ensure flexibility and protection for drivers. If you request a ride through the Uber app, you're warned that voting no on Prop 22 will cause you to pay more for increasingly scant rides. If you work as a driver for either company, or for similar companies like like DoorDash and InstaCart, you have been alternately bombarded by pro-Prop 22 messaging and asked to help promote the ballot measure.

But Prop 22 is not the attempt to guarantee flexibility or increased driver benefits that the near-infinite stream of mailers would suggest. Instead, the initiative is an attempt to continue squeezing the independent contractors working in the gig economy, as it would irreversibly prevent them from being classified and paid as employees. It is a brazen gambit, an attempt by some of the most powerful and exploitative forces in the state to use the sheer, ugly force of money to escape the regulatory scrutiny already enacted by state lawmakers. The twin ideas behind the push—that major companies are to be governed by a different, softer-edged set of laws and that those companies can grease any wheel with cash—are both true, if not exactly novel. What's different is just how overt it all is. This is an attempt to buy an indulgence that would exempt companies from a law that would complicate their business model. All the chicanery and astroturfing and bad faith direct-mail obfuscation can't conceal that.

The heft of the Prop 22's attempted stiff-arm is historic, but what truly sets it apart as a noteworthy case is the inherent admission by its funders that their multibillion dollar companies are not in fact the cutting-edge technology firms their founders have long touted. They are instead something older and simple—parasites, mostly, whose entire value hinges on how thoroughly they can manage to monopolize industries before regulations catch up to them. That's the game, and not only in this case, in this state. Prop 22 is more than an attempt to outrun legislation in California. It is the first of many battles to come across the nation, all of which will be fought to legitimize just this sort of exploitation.

The fight between disrupto-capital and gig labor that made Prop 22 possible began in April 2018, when the California Supreme Court decided Dynamex Operations West. v. Superior Court against Dynamex, ruling that the company had been misclassifying their drivers as independent contractors. The ruling established a new, stricter definition of independent contractor; going forward, employers that wanted to classify workers as contractors rather than employees would have to prove that all three prongs of what's known as the "ABC Test" applied to the worker in question. Those prongs were (A) the worker is free from company control; (B) the work being performed "is outside the usual course of the hiring entity’s business"; and (C) the worker has established that they are "customarily engaged" in the trade they're being contracted for.

Shortly after the Dyanmex decision, California lawmakers passed Assembly Bill 5, which cemented the court's decision as precedent and applied the ABC Test to every contract employer in the state. If the prospect of workers needing to switch from a 1099 to a W-2 seems like a minor change to you, rest assured that companies like Uber and Lyft feel quite differently when it comes to having to cover the benefits and protections offered only to employees, such as minimum wage, unemployment insurance, worker's comp, OSHA protection, and the legal right to unionize. AB-5 is a significant attempt to claw back labor rights for workers who have been unfairly misclassified as contractors and denied benefits they deserve. This is where Proposition 22 comes in.

The fact that big tech has railed against AB-5 is no surprise, but vociferous opposition from freelancers and small-time employers who rely on contract labor have made it one of the most contentious bits of recent state legislation. Labor law is so broken in this country, and union membership is in such a dismal state, and labor in general so atomized and fractured, that AB-5 invariably produced a few legitimate pain points. Confusing inclusions, such as the infamous limit of 35 pieces per media outlet per year for writers, infuriated the very constituencies the bill sought to protect. That 35-piece cap was one of over 100 exemptions for contractors in various industries that have since been carved out of the bill. Prop 22, which seeks such an exemption for app-based drivers, continuing to allow Lyft and Co. to underpay a fleet of contract-based full-time-ish drivers and seize more market share, looks deceptively like another one of those. This particular fight was always coming for AB-5, which was then and still is today aimed at the heart of the behemoths of the "gig economy."

Please note the quotes, there. As law professor Veena Dubal told me earlier this year, the "gig economy" is used euphemistically to promote the amorphous and debatable virtue of flexibility over something much more concrete—the inherent misclassification of workers that makes the business model of a company like Uber work in even the narrowest sense. In practice, earning anything close to a full-time wage through driving for a site like Uber requires long hours; over 70 percent of drivers work over 30 hours per week. The gig, which we might as well afford the dignity of calling a job, is also among the most dangerous in the country. “By not adhering to basic labor standards that employees have, drivers are often making far below the minimum wage,” an organizer with Rideshare Drivers United told me in January. “If this is your main source of income, that means you’re driving 40, 50, 60 hours a week. That doesn’t seem very flexible.”

The precise number of people whose livelihoods depend upon driving for such companies is oddly hard to pin down, although a 2016 study noted that almost all post-recession job growth has been in what's called "alternative work" arrangements. Even Google, long the Silicon Valley poster child for high salaries and plush perks, has more contract workers than full-time employees. The shift to contract work has accelerated both within the tech industry and the nation more broadly, but it's not an altogether new phenomenon. FedEx broke into the shipping business and established itself as a behemoth specifically by undercutting UPS through the aggressive hiring of a contract workforce.

But there's a different dynamic at work where the gig economy is concerned. Uber is a notoriously unprofitable company despite paying drivers as little as $5.64/hour, per a 2019 study; if they had to not only pay their fleet of drivers minimum wage but also provide them with employee protections, their already dubious value proposition would change dramatically. It is a perverse fact of life for venture-backed companies like Uber that profitability is not only not essential, but very much beside the point. For a company that aims to bust out established industries like taxi and livery drivers, the only things that matter are maximizing market share and, if mostly for the sake of tech-besotted investors, the Quixotic push for automation. Until cars can drive themselves, the only way to get anywhere near where investors want to be is by paying drivers as little as possible in terms of wages and benefits in hope of keeping prices artificially low. For them, the extraction is the juice.

The CEOs of both Uber and Lyft admitted in a joint op-ed for the San Francisco Chronicle last year that complying with the letter of the law "would pose a risk to our businesses." And so, in the two years since the passage of AB-5, they have fought that law in the courts and in the press while simply refusing to honor its guidelines. Following those rules would be the end of their businesses, and the combination of those companies' towering wealth and a regulatory state atrophied by generations of austerity made it something like a fair fight. It's a testament to the political capital these companies been able to acquire that it took this long for regulators to actually put them in their scopes.

This May, California AG Xavier Becerra sued the rideshare companies for refusing to comply; in August, a California court ordered the two companies to classify their workforce as employees within 10 days. They responded by threatening a capital strike and claiming that they might have to stop operating in California. They transparently would not ever do that—the state accounts for 16 percent of Lyft's business and 9 percent of Uber's, and also both companies are based here. Their bluff worked anyway, and an appeals court gave them another extension to submit an implementation plan.

This brings us back to Prop 22. Because the rideshare companies and similar aspiring monopolists like DoorDash and InstaCart can only thrive in a world without AB-5, they have put a combined $199 million into passing the ballot measure. Uber and Lyft are in for about $50 million each, with DoorDash, InstaCart, and Postmates in for a net $86 million. This makes it by far the most expensive ballot initiative in state history; the ludicrous haul is roughly one-seventh of the total amount of money Joe Biden has raised in his presidential campaign. Prop 22 doesn't just exempt drivers from earning employee protections, either. It makes the change essentially permanent. The full text of the bill reveals that reversing the law would take a 7/8ths majority of legislators. Given how easily Uber and Lyft can buy politicians, the law would effectively be tattooed forever into the books.

California's electoral structure is defined by the ballot measure system, a baroque experiment in direct democracy that, in theory, gives citizens the power to enact legislation. In practice, though, the system uniquely lends itself to powerful people brute-forcing self-serving bespoke laws onto the books. I could get a measure on the ballot that would designate the Golden State Warriors a terrorist organization next year if I simply paid enough money to get the requisite signatures and approvals. Two years ago, Californians voted in favor of a measure requiring all eggs sold in the state to come from cage-free hens by 2022. The Mormon church was able to spend their way into briefly banning gay marriage in 2008. The most infamous ballot measure in state history was 1978's Prop 13, which capped property taxes and has kept billions of dollars from being put to public use ever since. That one's still on the books, too.

The spending on Prop 22 dwarfs decades of competition, and the nine-figure outlay has bought the tech companies behind the effort more than just ubiquitous TV advertising.

- They have spent big on consultants who have harassed and intimidated proponents of labor rights, like Veena Dubal. The 19 big-time PR firms hired by the five companies pushing the law have previously worked with Monsanto, Chevron, and Phillip Morris.

- They have made big ad buys in some of California's biggest newspapers, and the San Jose Mercury News and the San Francisco Chronicle both endorsed 22. Neither disclosed the spending.

- They bought the endorsement of the state's NAACP leader for $85,000, and have relentlessly tried to frame keeping drivers as contractors as a social justice issue, somehow.

- Even more cynically, they've funded a widespread faux-progressive mailer campaign sent by fake groups like "Feel The Bern Progressive Voter Guide," "Our Voice, Latino Voter Guide," and "The Council Of Concerned Women Voters," in an attempt to make it seem like Bernie Sanders endorsed the measure and that voting yes on 22 was the progressive choice. Sanders has, of course, come out hard against 22.

Got two identical mailers, one from “the council of concerned women voters” and one called “Feel the Bern Progressive Voting Guide” clearly meant to signal association with Bernie— both saying to vote yes on Prop 22. Nasty, shady bullshit cc @PplsCityCouncil @KNOCKdotLA pic.twitter.com/cKRRxmuIH3

— Brittany Van Horne (@_brittanyv) October 9, 2020

- Users of the apps in question have been flooded with messages about the urgency of passing Prop 22, as well as dire warnings about how drastically their lives will change if app-based services go away or cost more money. (Anecdotally, one friend voted yes on 22 because he thought a no vote would ban all independent contractors.)

This $200 million messaging war is the biggest such undertaking in state history, though for a quintet of companies worth a collective $100 billion, it's a necessary investment. Uber says they'd have to cut three-quarters of their drivers if Prop 22 fails, though Berkeley economist Michael Reich crunched the numbers and disagreed with that scare tactic. If the measure fails, Uber et al. will have to give drivers twice as much per "engaged mile," which will have the cascading effect of higher prices and potentially lower demand. That would not be an issue for most normal companies, which exist to sell goods or services to consumers, but that's not the business model of our pals here. They are in the monopoly business, which means taking on massive debt, aggressively cratering existing industries, and finding cracks in the labor code to leverage. The many millions of dollars they lose every year are all aimed at the long-term goal of not just dominating but becoming their industries.

The public-facing argument from Uber in particular is that it's a technology company. Drivers are not central to our business, they've argued, because it's really about our innovative tech. The lie that Uber is propelled by an algorithm and not the combination of a large contract workforce and shameless regulatory arbitrage is one of the core contradictions of Silicon Valley. Often, what's marketed as slick AI or a bleeding-edge algorithm is really just people, in a room, processing data. I am reminded here of Charles Redheffer, an infamous fraudster from the early 1800s who roved from state to state selling tickets for yokels to come check out his perpetual motion machine. His apparatus was not, as he claimed, an affront to God and the first and second laws of thermodynamics; there was just a little man turning the cranks on his own. Innovations really do exist, but marketing bullshit is much more common.

Even Palantir, the most opaque and menacing of the major tech companies, relies heavily on what was recently reported as RFOP: "Rooms Full of People, meaning the army of analysts required to clean up the data and crunch the numbers." Time and again, these promises of sophisticated algorithms and automation reveal themselves to be janky Juicero-style reinventions of the wheel. Demystifying these sorts of myths is crucial to re-centering labor as we head into a future haunted by both the newfangled threats of artificial intelligence and automation, to the extent that they are also not bullshit, and bosses' longstanding passion for finding ways not to pay the actual people that make businesses work.

The scariest side of Prop 22 is less what it will do to rideshare drivers in California in the immediate future than the ominous precedent it would set. The Labor Department under Donald Trump has pushed to let companies misclassify employees as contractors across the nation, and the attorneys general for 24 states sent a letter to the DOL this week asking for the proposed change to be rescinded. If Trump wins on Tuesday, labor law is going to be fucked whether Prop 22 passes or not. If Joe Biden wins, one of the people in contention for Secretary of Labor will be Seth Harris, who was second-in-command in that department under Barack Obama and also happened to write a policy paper that helped Uber and Lyft form their legal argument for misclassification. As the Prospect wrote, Harris left the Obama White House in 2013 to work for one of the biggest law firms in the world and has pushed for an increase in "independent workers."

Biden has said he's against Prop 22, but clearly this fight is not a partisan issue, or not merely that. It is about something elemental and old, the fundamental conflict between labor and management. Whatever happens with the election tomorrow, both federally and within the state, the future of work in this country is going to look very different in 20 years. Ensuring a better future in the face of catastrophic climate change and, well, robots, will take organization, but it will also be won through one outwardly dull feat of legislation and governance after another. Defeating Prop 22 would be a hell of a start.