The roles of storyteller and play-by-play announcer are not as inherently married as Vin Scully made them appear. A storyteller knows his ending before he begins, and as such has total freedom over the structure and pacing of his tale, adding or subtracting details to go on for as long or as short as he wishes. Being a play-by-play announcer, on the other hand, is about reacting to spontaneous events: finding the words as you go while waiting for the end to be revealed to you. When narrating a broadcast, these two jobs sit in a precarious balance. A heavy emphasis on stories minimizes the on-field action that you're supposed to augment, while too much straightforward play-by-play dulls the experience for the listener.

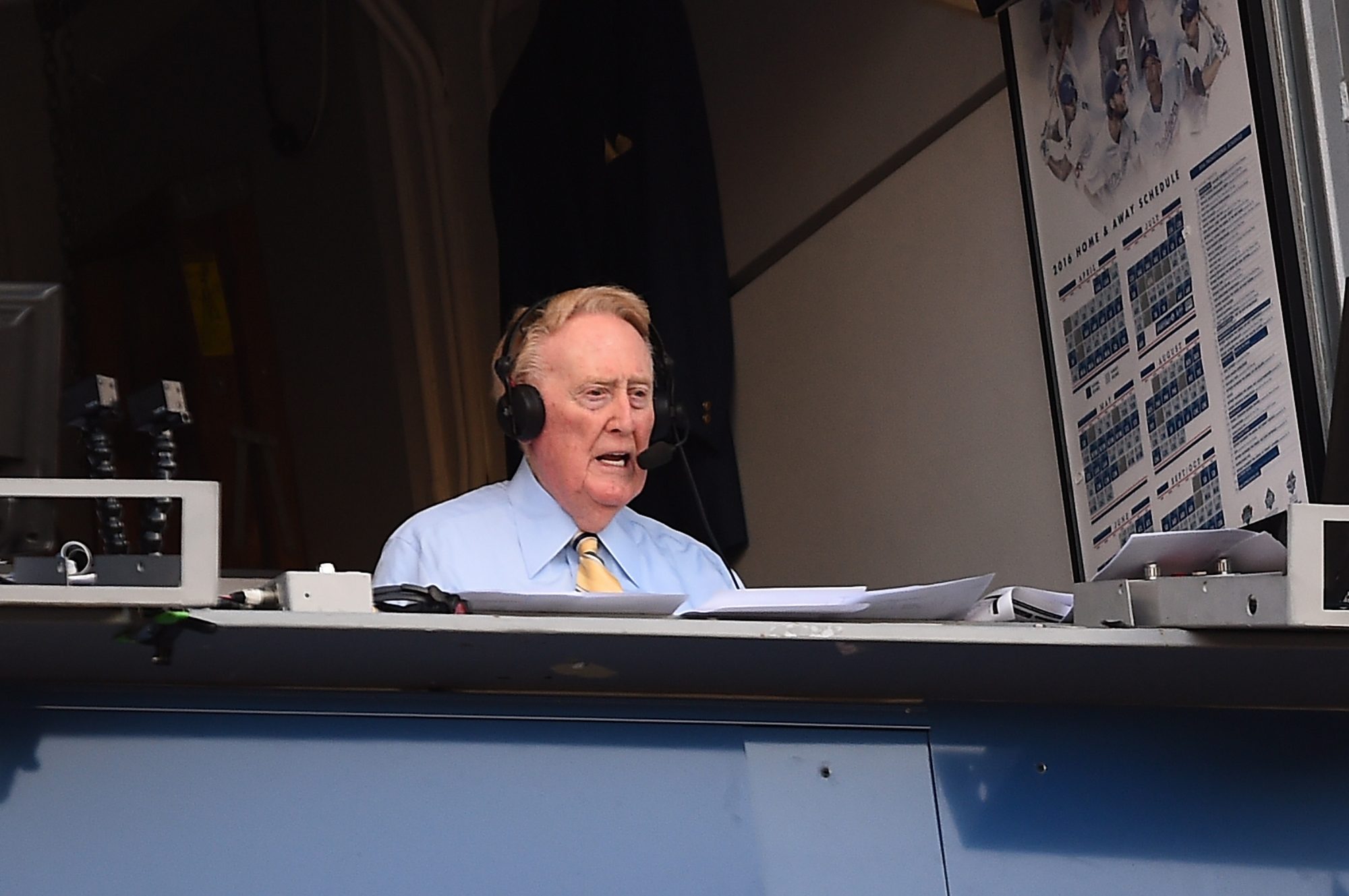

Scully, who died Tuesday at age 94, seemed to always get it just right. The stories he told in the booth weren't just unpredictable, compelling, and intelligent, though they were all of those things, but they also slotted perfectly into whatever was happening in the ballgame, as if the Dodgers announcer had a script that allowed him to know how many pitches he'd have before anything on the field would require his full attention. Armed with a deep well of knowledge about but not limited to the sport, and typically freed from the need to accommodate a partner on the broadcast, Scully's soliloquies on the microphone were so precisely paced and snugly placed within the play-by-play that they often gave the impression that the developments on the diamond were being dictated by the words from the booth, and not the other way around.

Take this story Scully told about a young Jonny Gomes's encounter with a wolf at his grandmother's house. The at-bat lasts six pitches, and Scully begins the story ahead of the third. He sets the scene and then gets to the suspenseful action just as the fifth pitch arrives. "The wolf attacks him, has knocked him down, is on his chest, just about ready to devour him," Scully says during the 2-2 delivery. It's ball three, when a strike would've interrupted the story and broken the tension. Instead Scully is able to seamlessly wrap up the story just as Gomes makes contact for a base hit.

Vin Scully tells the story about when Jonny Gomes survived a wolf attack when he was 12-years-old 🐺 pic.twitter.com/qmAJQJCjDq

— Baseball Quotes (@BaseballQuotes1) December 8, 2020

If the game often felt like it waited until Scully was ready, it was a testament to his command of the rhythms of storytelling. Take this yarn about Giants pitcher Madison Bumgarner killing a snake with an ax, and then his wife helping rescue a baby jackrabbit it ate, which gets spun by Scully without anyone at the plate daring to make contact. Finally, just as he reaches the end, a base hit moves a runner into scoring position and demands a refocus on the field. And then Scully finds a way to add the moral of the story as a postscript in that moment before the critical next batter steps into the box.

Vin Scully talks about the time Madison Bumgarner saved a baby rabbit by killing a snake during an off day in Spring Training 🐍🐰 pic.twitter.com/K8SHa75ocH

— Baseball Quotes (@BaseballQuotes1) January 15, 2021

Here's another animal story, this one about a poodle, and again it's like the game stands still to prevent any distraction that would hinder Scully's telling.

RIP Vin Scully. Here’s an incredible story he told on the air during a national Pirates-Cubs game back in 1988. pic.twitter.com/9NvHXbC7p2

— Andrew Fillipponi (@ThePoniExpress) August 3, 2022

Replaying even the small Scully moments can reveal the amazing way that the road rose to meet him. Here's a bold choice in an otherwise innocuous list of birthdays:

"There's one other birthday that nobody talks about [crack of the bat], as Trumbo fouls it back. Today is also Adolf Hitler's birthday," Scully says, tagging the birthday boy with a pair of scornful Ptooeys. If Trumbo had made more solid contact in between the setup and finish, this could have been a mess. You never want to have to circle back to Hitler's birthday. But the tempo of the game again slowed to let Scully make his point.

What happens when it doesn't quite go as planned? We get a peek behind the curtain, just for a moment, to see the genius at work in this clip, where Scully runs through the importance of beards throughout human history. He starts this digression with two outs in the top of the second, anticipating that he'll return to it throughout the game. But the Padres keep extending the inning, and with each new batter, Scully is able to start a new chapter of beard history but also satisfyingly close it out just before each at-bat ends, so listeners won't be left with a cliffhanger if the game must go to commercial.

My favorite Scully moment, however, defies any kind of analysis. It happens thanks to Sócrates Brito, who played 99 games across four seasons. Scully is enamored with his name and, true to form, is completely prepared to shade his at-bat with information relating to the Greek philosopher, and the hemlock he drank after being sentenced to death. Brito quickly gets into an 1-2 hole, but as usual, the at-bat continues on a little longer than it might have in order to let Scully share what he knows. What's most spectacular is the end, in which Scully says "That's what took Socrates away" literally just as Sócrates swings and misses at strike three.

Here's Vin Scully using the name "Socrates Brito" as an excuse to give a short lesson on the life of Greek philosopher Socrates and what hemlock is, while not missing calling a pitch pic.twitter.com/eH039sdWLw

— ℳatt (@matttomic) August 3, 2022

Scully didn't stumble into his timing and rhythms by chance. He achieved them with his ongoing curiosity about the world and through the work he put in calling thousands and thousands of games. Commit yourself that completely to your craft, and you likely do begin to possess a sixth sense that anticipates the right time to begin an anecdote and the time to hold it off for later. Over the years, Scully's baseball instincts became just as good if not better than the greatest who ever played the game. But for us on the outside, who can't comprehend what it's like to announce 67 seasons of games with the same franchise, we can only really express awe. A mastery of the job as deep and thorough as Vin Scully's can start to sound indistinguishable from magic.