This week, Defector has turned itself over to a guest editor. Brandy Jensen, former editor at Gawker (RIP) and The Outline (RIP), and writer of the Ask A Fuck Up advice column (subscribe here!), has curated a selection of posts around the theme of Irrational Attachments. Enjoy!

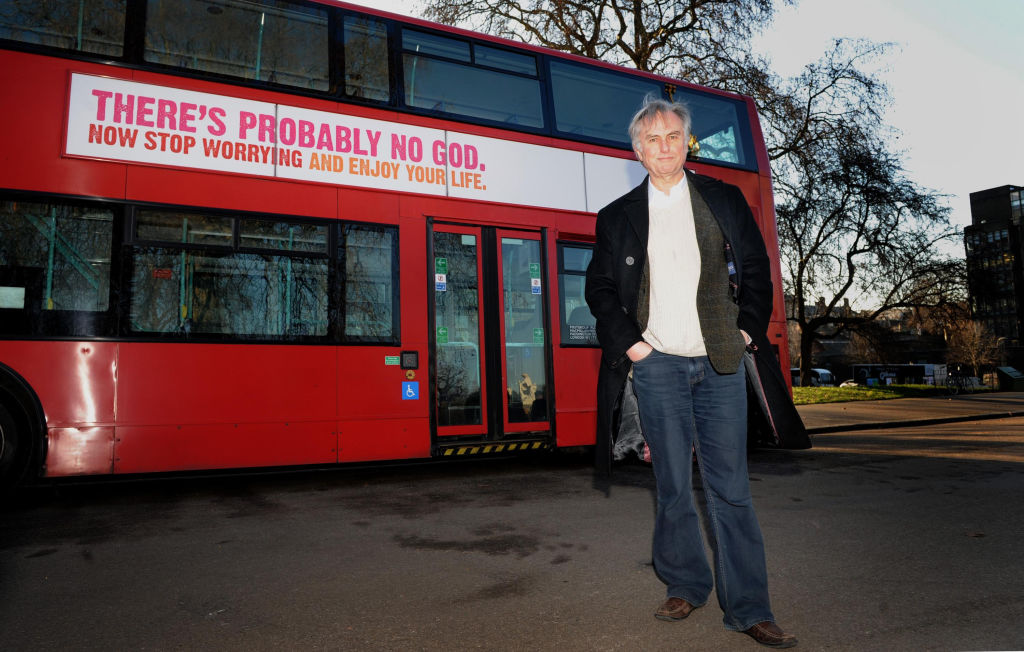

New Atheism feels today like Livestrong bracelets or Animal Collective: an embarrassing relic of the aughts. It has now been 13 years since Christopher Hitchens got to discover at last whether hell is real. The philosopher Daniel Dennett, by far the most intellectually reputable of the so-called “Four Horsemen” of New Atheism, is now dead too. Its living eminences mostly resurface to remind the world of how obnoxious they are. Richard Dawkins, evolutionary biologist, New Atheist polemicist, and author of some of the most unhinged tweets of all time, made headlines in April for referring to himself as a “cultural Christian,” as part of a broader tirade in defense of Western chauvinism. Sam Harris, the last of the Four Horsemen, has been podcasting apologies for Israel’s massacre in Gaza for months: You’ll be shocked to learn that he too sees it as a war between Western civilization and Islamic barbarism. A lesser-known New Atheist equestrian named Jerry Coyne—author of a blog titled, with the philosophical sophistication characteristic of the movement, Why Evolution Is True—is alleged to have spit on an anti-genocide protestor at the University of Chicago, where he is an emeritus professor of ecology. (Coyne told the Chicago Maroon that he "did not spit on demonstrators or on anybody else.") These are not serious people.

The easy thing to do would be to take these latest humiliations as a kind of Scooby-Doo unmasking: Turns out it was bog-standard neoconservatism all along! Not so scary anymore. Critics who have charged since its early days that New Atheism is a mirror image of its religious fundamentalist nemeses have plenty of reason to feel vindicated by the antics of figures like Dawkins, doing everything but announcing the formation of a new secular branch of Focus on the Family. The spectacle the movement’s senescent standard-bearers have made of themselves since October practically cries out for a religious horseshoe theory: Extremes converging, as they tend to do.

But we should hold off on publishing New Atheism’s obituary. I think the relevant image here is not Scooby-Doo but Obi-Wan Kenobi. Struck down in its old age, New Atheism has become more powerful than ever, transforming into an invisible, miasmatic presence: nowhere and yet everywhere, a ghostly whisper in the ear of unsuspecting proteges. Everything that distinguishes New Atheism from mere secularism—its crude worship of the supposed Western tradition of Reason, its smug contempt for the irrational masses, its insistence that every disagreement with its perspective can be explained by ideologically motivated ignorance—increasingly infects mainstream liberal discourse on a range of disparate topics. A miniature Richard Dawkins, like the worm that consumed part of Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s brain, seems to have insinuated itself into the cranial cavity of the respectable centrist media. And now it’s going to town.

The important thing to understand about New Atheism is that it was never primarily a theological position. Plain old-fashioned atheism is hard to innovate on in that respect. If one does not believe in God, there is not really much more that needs to be said about one’s religious beliefs. In fact, New Atheism was, at its root, not about religion at all. It was about science, and its original enemies were not fundamentalists of any faith but a group of atheist Marxist biologists. Before Richard Dawkins and Daniel Dennett—the oldest of the group—were best known as professional atheists, they came to fame as defenders of the idea now known as evolutionary psychology, which began its life in the 1970s as “sociobiology.” Dawkins and Dennett championed the perspective of the biologist E.O. Wilson, which held that Darwinian evolution by natural selection was able to explain the reasons for a wide range of human behaviors, social patterns, and habits of thought, which were in turn thought to be significantly determined by a person’s genetic makeup. Their opponents, including most famously the leftist Harvard scientists Richard Lewontin and Stephen Jay Gould, maintained that sociobiology was built on shoddy scientific foundations and downplayed the importance of history, not just biology, in explaining why our societies are the way they are. To them, sociobiology was the rebirth of eugenics and social Darwinism in a kinder, gentler disguise.

Around the turn of the millennium, Dawkins, Dennett, and allies like Steven Pinker came to a very clever realization. Fundamentalist Christians also disagreed with them about evolutionary science—because they denied human evolution outright. As a result of the political power the religious right had accumulated since the 1970s, evolution had become a hot-button culture war issue. The sociobiologists (now rebranded, savvily, as evolutionary psychologists) had an opportunity to cast themselves as staunch defenders of science and rationality in debates about high school science education, stem cell research, and the like. Gould and Lewontin, despite their materialist commitments, refused to embrace this framing: Gould, for instance, argued that science and religion were “non-overlapping magisteria” that, properly understood, provided answers to fundamentally different questions and therefore couldn’t be said to be in “conflict.” The evolutionary psychologists exploited their enemies’ weakness for nuance. Any refusal to join Team Science in the fight against Team Religion, they charged, revealed that the supposedly scientific criticisms of sociobiology were really symptoms of an ideologically driven disloyalty to Darwin and the evolutionary paradigm. To “believe in evolution” meant to agree with Dawkins, Dennett, and Pinker—which meant to disagree not only with Jerry Falwell, but also with Lewontin and Gould.

New Atheism came into its own during the Global War on Terror, when secular neoconservatives like Hitchens realized that the arguments being used against Anglo religious fundamentalism could be wielded very conveniently against Islamic radicalism. This offered a way to challenge the common antiwar framing of the U.S. invasion of Iraq and other Bush-era military operations as a new Christian crusade against the Muslim world. Instead they could, against all odds, depict Bush as an almost unwitting agent of a great campaign to defend the Western Liberal Enlightenment Tradition (which reached its height in the great discoveries of modern science) against the cave-dwelling barbarians who wanted to reinstate the Dark Ages. The New Atheists of the aughts constructed an insidious conceptual conveyor belt: rejecting creationism meant believing in capital-S Science, which meant believing in Western Civilization, which in turn meant supporting or at least tolerating imperialist American wars in west Asia. Conversely, disagreeing with the New Atheists—opposing the War on Terror, doubting their just-so-stories about how evolution explained this or that human behavior—meant rejecting capital-S Science, and maybe even rationality itself.

The New Atheists had a convenient explanation handy for why so many apparently respectable, educated Westerners found themselves on the side of irrationality: It was evolutionary. Capitalizing on the prestige attached to the field of behavioral economics, which presented a range of empirical findings on the ways that real humans deviated from neoclassical economists’ models of rationality, evolutionary psychologists have spent much of the 21st century coming up with stories about how evolution has made us, as the title of one book has it, Predictably Irrational. One of the irrationalities they are fondest of pointing out is what they like to call “myside bias”—or, in order to gesture towards an evolutionary explanation, tribalism. As Dawkins observes, there is “disturbing experimental evidence that what we believe is heavily swayed by loyalty to our team (e.g. left or right political leaning) rather than purely, as it should be, by evidence.” The wonders of science never cease.

The irony, of course, is that the New Atheists invoke myside bias to draw their own battle lines: between the team that uses “evidence” to transcend ideology, and everyone else, who are instead irrational, “political,” trapped inside their imaginations. Science vs. Religion has evolved into Rationality vs. Tribalism. Rationality allows one, through rigorous scientific methods, to make contact with reality; those in the throes of Tribalism encounter only the world created by its wishful thinking. The world is divided into people who want to know how things really are and people who refuse that knowledge because it conflicts with their prejudices. At the heart of New Atheism is a fanatical enthusiasm for reality. And like other fandoms, it guards its interpretations of the object of its obsession jealously.

It is this legacy we are still contending with today. Since roughly 2014, takeslingers across the prestige media landscape—and at the New York Times and The Atlantic in particular—have declared their allegiance to Team Rationality in droves, dutifully going to the mat against the forces of Team Tribalism wherever they can be found. (This, it turns out, is mostly on college campuses.) When Steven Pinker wrote, in his 2002 book The Blank Slate, that “discoveries about human nature were greeted with fear and loathing” by critics like Lewontin and Gould “because they were thought to threaten progressive ideals,” he was as often as not received by humanistic-minded liberals as a tendentious crank. Louis Menand delivered the New Yorker’s verdict: “Jesus wept.” Two decades on, the belief that “progressives” instinctually reject any evidence they don’t like is ironclad dogma in opinion pages nationwide.

Recently this premise has loomed especially large in the conversation surrounding two apparently unrelated issues. The first is Palestine, and the student protests against their universities’ investments in companies complicit in the slaughter. This position, it turns out, is just another manifestation of myside bias. Former Iraq War cheerleader Jonathan Chait bemoans the way that “Trumpian conservatives” as well as “radicals on the left” both argue that the Israel-Palestine conflict “pits good against evil and that compromise is unthinkable.” These apparent enemies are really both on Team Tribalism––equally simple-minded in their respective positions that Palestinians should be exterminated, on the one hand, and that genocide is bad, on the other––while members of Team Rationality, like Chait, recognize that the conflict “is complex and has faults on many sides.” Even an opponent of crackdowns on campus protest like Zadie Smith can’t resist assailing the protestors for using language “to flatten and erase unbelievably labyrinthine histories, and to deliver the atavistic pleasure of violent simplicity to the many people who seem to believe that merely by saying something they make it so.” Steven Pinker, who joined other reactionary faculty members in lobbying Harvard administrators to forcibly crush their school’s encampment, couldn’t have put it better himself.

The second issue is trans rights. Just as New Atheism helped to legitimize the War on Terror among self-identified science believers who’d ordinarily never think to ally with evangelical Christians, the charge of progressive irrationality has helped to legitimize transphobia among precisely the same demographic. Again, what appears as a fight between the left and the right turns out to be a conflict between irrationality and a clear-eyed consideration of the evidence. “Right-wing demagogues are not the only ones who have inflamed this debate,” Pamela Paul wrote earlier this year in one of her many New York Times screeds against trans activism. Advocates of trans acceptance, too, “have pushed their own ideological extremism,” according to Paul, while those sober rationalists “who think there needs to be a more cautious approach” have been unfairly “attacked as anti-trans and intimidated into silencing their concerns.” One prominent defender of the Times’ preoccupation with “questioning” the appropriateness of medical care for trans youth has been, go figure, Jonathan Chait, who once again argues that ideologues on both sides have neglected the importance of “carefully following the evidence,” wherever it may lead.

It's not just Chait: The correlation between just-asking-questions transphobia and hostility towards pro-Palestine activists is astonishingly high. Among the community of aging New Atheists, both positions are practically obligatory. Jerry Coyne, the UChicago protest spitter (allegedly!), has also taken an obsessive interest in the issue of trans people’s participation in women’s sports. To determine if “someone is an extreme gender activist,” Coyne writes on his Why Evolution Is True blog, you should “ask them if trans women, born as biological males, should be allowed to compete against biological females in women’s sports.” If they answer in the affirmative, he writes, it means they are “ignoring the palpable data on the physical advantages of transwomen.” Richard Dawkins, meanwhile, when he is not urging Christendom to go to war against Islam, spends his time slandering trans identity as “a distortion of reality.” Your brain on New Atheism, apparently, looks an awful lot like your brain on Fox News propaganda.

There’s nothing wrong, of course, with trying to figure out what reality is like. Some of my best friends are real. The problem is that reality isn’t fixed. It is not merely complex, as liberal handwringers point out incessantly. It is contradictory, riven by forces pulling it in different directions. It changes, and it changes not least because we change it. In trying to freeze reality into a cudgel that can be used to assault political opponents, the New Atheists and the liberal pundits who consciously and unconsciously imitate them end up committing the sin they claim to hate the most: They deny the observable evidence in front of them. It is entirely backwards to try to determine whether sex is immutable “in reality” in order to assess whether it’s “really possible” to change sex. In reality, people change their sex, so it cannot possibly be the case that sex is immutable.

For the same reason, it is a mistake to fault advocates of justice in Palestine for failing to understand the “reality” of the conflict, because it is this reality that they are participating in and reshaping. There is no essential thing called “the Israel-Palestine conflict.” There is just a place between the river and the sea, and the reality there is dependent, for better or for worse, upon the outcome of political struggle. Reality is a historical process, as Lewontin and Gould argued against the sociobiologists long ago. New Atheism will continue to haunt us for as long as we refuse to acknowledge that the way things are always includes the possibility that things could be different.