When 16-year-old Allana Slater stood at the end of the vault runway before her timer warm-up during the third rotation of the 2000 Olympics women’s all-around final in Sydney, she almost immediately knew that something was off. “I was looking at it and thinking, ‘That looks wrong. That looks low.’”

The Australian gymnast recalled saying as much to the other athletes around her, but her fellow competitors were too focused on preparing to warm-up for their third rotation of the all-around final to respond. Slater considered the possibility that she was losing it, or just feeling extra sensitive a few days after falling twice on the vault, her weakest apparatus, in the team qualification round. Slater and her coach had spent a lot of time on vault before the all-around event, trying to work out her technical issues and ultimately deciding to downgrade her vaults to one she was guaranteed to hit in competition. As she prepared for her timer, which is an easy vault that a gymnast performs in the warm-ups to get a feel for the apparatus before they warm-up their difficult tricks, she knew full well that this event was hard enough when everything was where it was supposed to be.

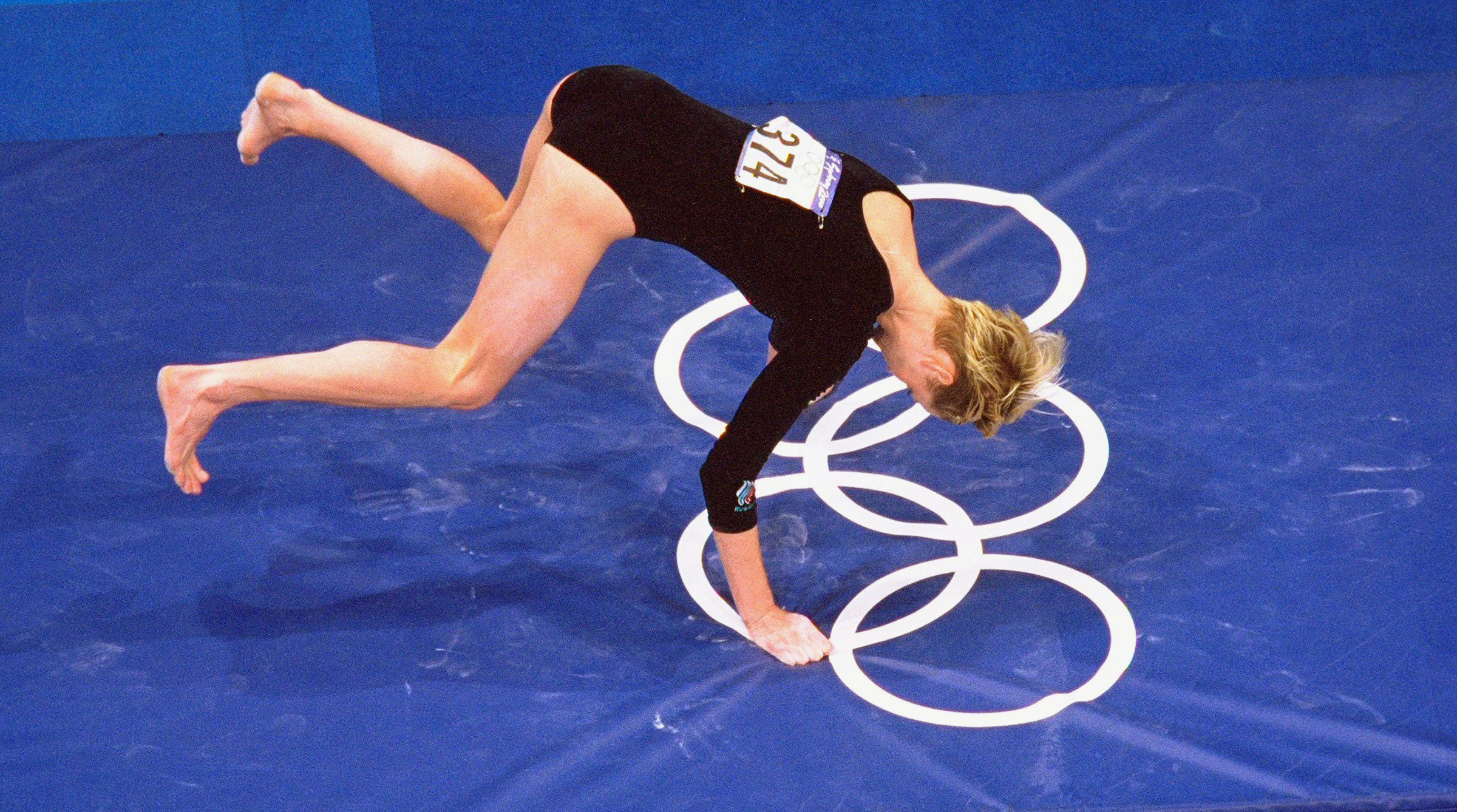

Slater was up first in the rotation, and by the time she got to the end of the 70-foot runway she knew that everything was not where it was supposed to be. “I knew as I was entering onto the horse that it was wrong,” she said. Then just five feet tall, Slater was used to hitting straight into the side of the horse rather than dropping down from a high angle, which she said never happened. This time, though, she did. After rolling out of her timer, she wanted to take a closer look. “I walked up to it and I was sort of measuring it up against me,” Slater explained. “Everyone knows roughly where the vault comes up to on their body.” And so she stayed on the mat, grinding the typically chaotic vault warm-ups — springboards are moved closer or farther depending on the needs of the gymnasts, coaches and competitors add chalk marks to the runway to signal to the athlete where to hurdle — to a halt. Slater knew something was off, and if it was off for her it would have an impact on every other competitor. It was the beginning, but by no means the end, of the most wildly messed-up major event in the history of women’s gymnastics.

Start here: by the time Slater alerted the officials, half of the 36 women in the field had competed on the low vault. The first two rotations on the apparatus had been filled with falls, many of them from gymnasts who seldom fell. And some of those falls were downright terrifying, with gymnasts barely getting their hands onto the apparatus or missing it entirely. Annika Reeder of Great Britain suffered a lower body injury in the second rotation and had to withdraw from the rest of the competition, which would turn to be her last of her career. It could have been worse. The margin for error was incredibly small on the old vaulting horse, which was easy to miss even when the equipment was set up properly. In the late 1980s, as the Yurchenko-style vault — a roundoff onto the springboard back handspring into the vault — became popular, the sport saw a number of serious spinal cord injuries; some were even fatal. (Recognizing the safety risks posed by the narrow horse, the International Gymnastics Federation (FIG) switched to a much safer vaulting table in 2001, a change which had been planned before the vault debacle of 2000.)

“It’s the Olympic Games all-around finals,” Slater said. “I’m sure the judges were looking at me, thinking, ‘What is she doing? She lost her mind?’” But Slater stayed put and told coach Nikolai Lapchine that the vault was set wrong, standing next to the vault to show that it hit her almost at her hip, lower than it usually did. “I haven’t grown overnight,” she told him. Lapchine stood next to it to measure it against himself. Once Slater had convinced her coach that there was a problem with the apparatus, Lapchine went to talk to the judges and officials and she finally got off the mats and waited.

“Before I knew it, there’s a tape measure coming out,” Slater remembers. “There are all these officials from the top WAG [women’s artistic gymnastics] technical committee standing around the vault.” Finally, Kym Dowdell of the Australian delegation motioned upwards with her hand, instructing the apparatus officials to raise the vault. It had been set one notch — that’s five centimeters — below the international elite standard for the women.

On that day, thankfully, there were just a lot of scary near misses, and one open question that has persisted over the two decades since the women’s all-around in 2000 — what if the vault had been set at the right height? “It affected everybody on that day,” Slater said. “It affected everybody’s outcome. You know, what would have been?”

When gymnastics fans talk about the vault debacle at the Sydney all-around final, two gymnasts get mentioned more than any other: American Elise Ray and Russian Svetlana Khorkina. The former took what was probably the most terrifying fall on the low apparatus; the latter was the favorite to win the all-around title, having qualified into the final in first place. She was in first place until she encountered the low vault and crashed to her knees, dashing her hopes of winning the gold medal she coveted. (Khorkina was a decidedly “gold or bust” gymnast.)

Ray was the one who really got the ball rolling on this disaster for her first rotation, the vault. The problem started in her warm-up, when the 18 year old from Maryland completely missed her hands on the apparatus; only by rotating to her back in the air did she avoid landing on her neck. (NBC, which broadcast this competition on a tape delay due to the time differences between Sydney and the states, made sure to get as many reaction shots to Ray’s warmup from gymnasts and coaches as possible.) Ray was fortunate not to be injured, but went into the biggest meet of her life rattled and completely demoralized.

“I didn’t watch that really scary vault until YEARS later when they showed it to me live during an interview,” she told me in an email. Ray, now Ray-Statz, is currently the head coach of the University of Washington’s women’s gymnastics team. “I immediately cried. I was flooded with ‘I’m so lucky that wasn’t worse.’ I thankfully knew where I was in that vault, at least enough to know that I needed to duck my head under.” This was a real testament to her natural air sense and her training.

“Usually I felt a block,” she wrote, “a repulsion off the horse. That block sets up your entire vault. But those vaults, I hardly came in contact with the horse at all, being that I was too high. Basically when you come in contact with the horse, that block propels you to go even higher, leaving you ample space to safely and successfully complete the flips and twists.” Without that block, there's nowhere to go but down.

Like many others who vaulted on the low apparatus, she had no idea why she had so thoroughly overshot the vault during the warmups. She had already done four competitive vaults in that arena on that particular apparatus while in Sydney, not to mention a raft of timers and warm-up vaults and a podium training session. So she did what athletes do. “I blamed myself.” Ray-Statz said. “[I] thought I was nervous, maybe my steps were off?” The gymnast and Kelli Hill, her personal coach, went back and checked the board setting and where her hurdle lines were marked in chalk on the carpet. She also checked her starting place on the tape measure. She never considered that the vault itself was at fault.

Gymnasts, Slater explained, are constantly making small adjustments in competition even under the best of circumstances, generally to account for things like the difference between the feel of a floor mat made by one manufacturer versus another. And there is a difference between competing on a podium and on the floor. The elevated podium, which is used for major competitions like the world championships and the Olympics, can slightly change the dynamics of your movements. “When you run on a podium, your steps become a little longer. Sometimes you have to adjust where you start your run,” Slater said. And some days you just might have more energy and end up taking bigger steps. “It’s so easy to go, ‘Oh well, I just need to make a small adjustment to my technique, my run, whatever it is ... It’s built into an athlete to make these tiny adjustments, easy to question yourself—and it is hard to step back for a moment and go, ‘Hang on a second.’”

When Ray stood at the end of the runway to go for her two competition vaults after her terrifying warm-up, she was not optimistic. “‘Well, here goes nothing,’” she thought. “Usually I had a very scripted mental rehearsal, positive affirmations, positive self-talk ... but after a warm-up like that and still not knowing was wrong, I didn’t know what to do. And there was no time to do anything; it was time to compete,” Ray said. She decided that she would run faster, go harder, try to get the vaults around to her feet even if she didn’t get much—or any—block.

And it worked, sort of. “At least that extra power got me around to sit it when I still had no contact with the horse.” Ray still fell, but not in such a way that she appeared to have narrowly avoided a serious injury. But the average of her two low scores put her in 35th position, second to last in the field.

The devastating all-around vaults were not the first bump in the road for Ray or the U.S. team in Sydney; most of the U.S. women on the 2000 team describe their Olympic experience and everything that led up to it as a nightmare. In the nine months leading up to Sydney, the American gymnasts were subjected to grueling training camps administered by the autocratic Bela Karolyi; new selection procedures meant that a committee, rather than results from Olympic Trials, determined the team composition, which made the process even less transparent than it normally was. The result was brutal for the athletes: weeks of training with no days off, lineup changes made at the literal very last minute, in this case as the team was marching into the qualification round of competition. The gymnasts did not get to stay in the Athletes’ Village or meet other athletes. “We were robbed of anything Olympic,” Ray wrote. “I had a sticky note calendar on the wall in my room. I would peel off one sticky note each day, which meant I was one day closer to being done.” (Three members of the U.S. team in Sydney—Jamie Dantzscher, Tasha Schwickert, and Morgan White—would later come forward as victims of former USA Gymnastics team doctor Larry Nassar.)

What happened to Ray in the days before the all-around final really informed what her mindset was as she prepared for the biggest competition of her life and how she handled the devastation of those two vaults in the very first rotation.

After what Ray and her teammates had already been through at the Olympics, she was exhausted by the beginning of the biggest competition of her life. After injuring her shoulder on the floor exercise during the first day of competition, she was not at her strongest. And after the devastation of her two vaults in her very first rotation, Ray was shaken. “There’s a certain level of physical and mental activation athletes need when competing,” Ray explained. “To get myself to a competition-ready level mentally and physically that day took everything I had. And I had done it! Before vault, I felt great! But then in one moment, one vault, it was gone. I felt lower than low. Energy gone, confidence gone. Deflated. I had a completely broken spirit because I knew what a fall on the first event meant. My chance at an individual medal was gone. Just like that.”

After falling on her two competition vaults, Ray sat in a chair with her grips half on when she was supposed to be preparing for her next event, which was the uneven bars, Ray’s best. Hill approached her and gently said, “‘Lucy,’ which is what she used to call me, ‘Lucy, you have to get your grips on.’” Then Ray went to the uneven bars and did one of the best routines of her life, introducing a new dismount, a double twisting double layout somersault, which, up until that point, had only been done off of men’s high bar. That dismount, along with two other elements on the uneven bars, now bears her name in the women’s Code of Points. I asked if she was able to enjoy that bar routine and getting another element named for her on her best apparatus. “No,” she replied. “I did not enjoy that moment. I was barely there.”

Khorkina’s hopes were also dashed by the low vault, too, but she started the competition in a better place, both physically and mentally. The day of the all-around final was no different and she had reason to feel confident, although Khorkina seldom lacked for that as a general rule. She was the 1997 world all-around champion and had won the European title the year of the Games; she qualified in first place for the all-around final. She and the Russian team underperformed and placed second behind Romania in the team final, and Khorkina and Elena Produnova ripped their silver medals off in disgust as they walked away from the team medal ceremony. This was a disappointment, but Khorkina doesn’t appear to be the type that internalizes her mistakes. According to her autobiography, Flic Flacs in High Heels, she entered the all-around final in Sydney quite assured that she was going to win. After a strong start on floor exercise she was in a good spot to do so headed into the second rotation, which for her was the vault.

“I’ve seen so many injuries on the competition floor that nothing scared me and at that moment, I was ready for anything and my mind was impenetrable,” Khorkina wrote. “Yes, I flew over the vault several times during the warmup but I thought that I just had too much power and too much excitement...I didn’t even realize that something was wrong with the vault ... No one could even think that the height of the vault was set incorrectly.”

In competition, Khorkina did the same thing as she did in the warmups. “I landed on my knees, smashing them. I couldn’t understand what happened, why the crowd gasped, and what I was doing on the floor.” Khorkina jumped up, saluted the judges and walked back down the runway to take her second vault. She managed to adjust and her second vault went very well. Still, with both scores being averaged, her fall brought her total down far enough that she was no longer a threat for the gold. Khorkina made it clear in the team event that she wasn’t interested in second or third place. “Without understanding that the horse was set incorrectly, I blamed myself. I didn’t just shatter my knees on that fall, I shattered my biggest dream.” (It’s worth noting that while Khorkina might have sustained some injury in the fall, she didn’t actually shatter her knees.)

Khorkina learned that the apparatus had been five centimeters too low shortly before she went to bars, the event where she was the defending world and Olympic champion, and fell on a release, landing on her knees once again.

Ray found out while waiting to go up on the balance beam. “I remember there being a very palpable buzz in the arena,” Ray recalled. There was no time for her to pause and process what she had just learned. The competition hadn’t been halted, not even for the two groups that had competed on the faulty vault, which were at bars and beam when Slater raised the alarm. They had no choice but to salute the judges and keep going. “I literally was about to go compete beam,” she said. “There was no time to internalize what it meant.” Ray mounted the balance beam and fell on her acrobatic series. Ray, Khorkina, and the rest were given the option to redo their botched vaults, but both would be counting a fall regardless since they weren’t given an option to redo any of the events that they competed on after falling on the mis-set vault.

Perhaps the only person who was energized by learning that the vault had been set wrong was Slater. She had trusted her gut, spoken up and been actually heard, and her coach had listened instead of presuming that she was making excuses. “To his credit he actually stopped in that chaos of an Olympic final and looked at me and listened to me and checked and said, ‘Yeah, you're right, this is wrong, we need to question it.'” After Slater’s hunch was proven right, the gymnasts in her rotation were allowed to do additional warm-up vaults. Slater’s went particularly well, boosted by the adrenaline rush she got from saving the last two groups of gymnasts. “I remember saying to my coach, ‘Can I try to layout my difficult vault?’” she said, referring to the vault she had downgraded after crashing on it in qualifications. “He’s like, ‘No, no. We do the tuck. Do it successfully.’” She did.

Ray, too, was successful on do-over vaults in the “fifth" rotation of the women’s all-around. “They felt like all the vaults I did in training for the months and years leading up to the Olympics,” she said. “Of course, the first thought upon landing both to my feet in competition was What if. What if I had landed these vaults [in] my first rotation?”

With her redone vaults and the beam fall, Ray shot up from nearly the bottom of the 36-person field to 14th in the women’s all around, which made her the highest ranking American in the competition.

Khorkina, however, decided against vaulting again. She had already fallen on bars, which meant that no matter how well she did on the vault redo, she wouldn’t be able to climb into first. “I lost my calm and left the arena, sending everyone to hell,” she wrote. (In media accounts of the scene, she is quoted as having said “Get lost” to the Russian media who were trying to question her.)

If you have gotten the sense that Khorkina was A Lot, you are correct. She has always been a polarizing figure, and since retiring in 2004 she has compared WADA to the Nazis and been unrelentingly shitty about Simone Biles, who has surpassed all of Khorkina’s medal tallies and records. But her reaction, and the decision not to vault again in the all-around, are much easier to justify. She refused to participate in the fiction that somehow the results of this all-around event could be made right, and that the incorrectly set vault didn’t delegitimize the entire event. (This isn’t anything against anyone who did vault again; all the gymnasts were caught in an impossible situation.)

The solution that FIG came up with on the fly belied the very nature of the all-around competition. The all-around is not just a tally of scores on four different apparatuses; the different events are all connected and the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. You can’t just redo one of the four and expect to have anything approaching a fair result. I reached out to FIG with questions about the administration of the all-around at the 2000 Olympic Games and haven’t yet received a response. At the time, the FIG’s Slava Corn seemed to minimize the enormity of what had taken place, saying that “mistakes sometimes happen.” Corn also said that the athletes had no recourse in the situation. Sports are supposed to offer life lessons and the gymnasts learned a hard one that day—you are sometimes forced to bear the consequences of other people’s fuck ups.

So what was to be done? “I think the meet should’ve stopped altogether in that moment when the mistake was discovered,” Ray said, echoing what Khorkina wrote in her autobiography. “Athletes and coaches should’ve been filled in on what happened, how it happened, what will be done so that it doesn’t happen again, and, of course, a sincere apology, none of which happened.”

At the time, when her coach asked if she would’ve wanted to redo the whole all-around competition—an option that was never presented to the athletes—Ray said “no way” because she was so beaten down by her whole Olympic experience, she told me back in 2015. She now believes that starting the whole thing over was probably the only appropriate way to address what the damage done by the vault. “In hindsight,” she said, “it seems to be the only fair [way to] even the playing field.” Because FIG opted for a quick fix, it wound up with an event that represents nothing more than institutional failure.

The record books for the women’s all-around in Sydney should have no names in it, or asterisks next to every single name. It had no winners.

Two decades after this historic clusterfuck, I’m not going to try to answer who would’ve won the all-around had the correct standards for the equipment been met. There’s no way for us to know short of some Butterfly Effect shit, and playing with the timeline is asking for trouble. Re-set the vault and who knows who might be president.

More to the point, trying to figure out who would’ve won is perhaps the least interesting way to think about this whole debacle. In sports, talk about a level playing field is seldom about the physical field of play upon which athletes actually compete and almost always about doping. The resulting intrusions upon athletes—on their physical beings, their private time that can be interrupted at any moment, their medical information—make them subject to various sports governing bodies. When the debate turns to “sex testing” women athletes, the indignities are even more dramatic. At every level, the institutions of sport have mapped the “level playing field” onto the athlete’s body.

That’s why when Andreea Raducan, the 16-year-old gymnast who won that tainted all-around final in 2000, tested positive for pseudoephedrine, which was then a banned substance, she was stripped of her gold medal. (Of course this story was going to get worse. I do not use the word “clusterfuck” lightly.) Raducan had a cold before the start of the all-around final and was given two cold pills by the Romanian team doctor; he also admitted to giving the same dosage to Simona Amanar, who had placed second behind Raducan, but because Raducan was a lot smaller than her older teammate she tested positive where Amanar did not. Though all parties agreed that Raducan didn’t try to cheat and likely didn’t enjoy any performance enhancement from the drug—that she was, in short, innocent— she was stripped of her gold medal all the same. The same authorities did, however, let Raducan keep her silver on the vault and her gold from the team competition; nor did they strip Romania of its team title, the reason being that Raducan didn’t test positive after the vault final or the team competition. It was the positive test—not an admission of having ingested a banned substance, no matter how intentional—that was taken into account. Raducan appealed to the Court of Arbitration of Sport, where Jacques Rogge, who would go on to be the president of the IOC, argued that while he recognized that Raducan was innocent, he didn’t think she should get her gold medal back. Raducan lost her case. Rogge described this experience as “one the worst experiences I have had in my Olympic life.”

It should be noted that the performance enhancing benefits of pseudoephedrine are debatable; this analysis calls any benefit “marginal” and says that the benefit is equivalent to about what can be derived from caffeine, which is allowed. Other analyses show that dosage matters a lot in terms of performance enhancing effects. A therapeutic dose, say the kind given for a cold, likely has no positive impact on performance, but at significantly higher doses, it might. In 2004, pseudoephedrine was removed from the banned list altogether, but was added back in 2010; the new concentration required to trigger a positive test is higher than it had been when Raducan was stripped of her medal. In 2015, Raducan spoke to IOC president Thomas Bach about being reinstated as the 2000 Olympic champion but her request was denied. (Raducan’s quest to get her gold back is the subject of the HBO Europe documentary, The Golden Girl.)

This means that this one luridly botched event offered two very different offenses against the so-called “level playing field.” One is defined by zero tolerance and saw a gymnast’s name scrubbed from the record books. In the other, only token half measures were taken to address the most fundamental unfairness by the institution entrusted with preventing it. It was convenient to sacrifice a 16-year-old kid for the sake of the system, but notably less convenient to restage an entire competition in the interest of fairness. The fact of this injustice is less surprising than its density; even in gymnastics, it is rare to see misplaced institutional priorities laid out so starkly in a single event.

To find something positive to take away from all this, we have to go back to the beginning—to a different 16-year-old gymnast who had the audacity to speak up, and who was actually listened to by the adults in charge. That alone is no small feat in a sport which has spent decades ignoring the voices of its young athletes. “I look back,” Slater said, “it’s probably one of my proudest moments ... Being courageous and saying something.”