Mel Greenberg, who will be honored by the Basketball Hall of Fame this weekend, is something like women’s basketball’s walking society pages. He tells stories exhaustive in detail and dense with names (mostly first names), each of them liable to explode into another four or five anecdotes without warning. If you're unfamiliar with the world he's shaped and charmed for 50 years, you might find yourself, mid-conversation, wishing for footnotes or a glossary.

Let's start with some immersion. I'll do my best to translate: At a recent party ESPN threw to honor Carol (Stiff, the network's head of women's sport's programming) for being inducted into the Women's Basketball Hall of Fame in Knoxville, Greenberg caught up with Robin (Roberts, the broadcaster), who cried, "Oh, the legend's in the house!" when she saw him; spotted Connie (Hurlbut, a senior associate commissioner at the West Coast Conference); and told Lynn (Holtzmann, the NCAA's vice president for women's basketball) he didn't have her cell number, just her office line. He wanted to ask her about something about Rick (Nixon, an NCAA associate director). Lauren (Jackson, the seven-time WNBA All-Star), a member of both the Knoxville and Springfield classes this year, couldn't make to it to the States for either ceremony because of coronavirus protocols for re-entry in Australia. The scattered absences aside, the Knoxville trip went well; last year's event was canceled amid the pandemic, so it was nice to see old friends again. "I kind of feel like we've got to do a whole bunch of reconnecting and starting over," a coach told Greenberg the other night, a feeling that rang true for him, too. Anyhow, the WBHOF ceremonies have become a little less glamorous over the years. Debbie (Antonelli, the basketball analyst) does the opening remarks, but they don't do introduction videos anymore and at some point they got rid of the orchestra. Did you get all of that?

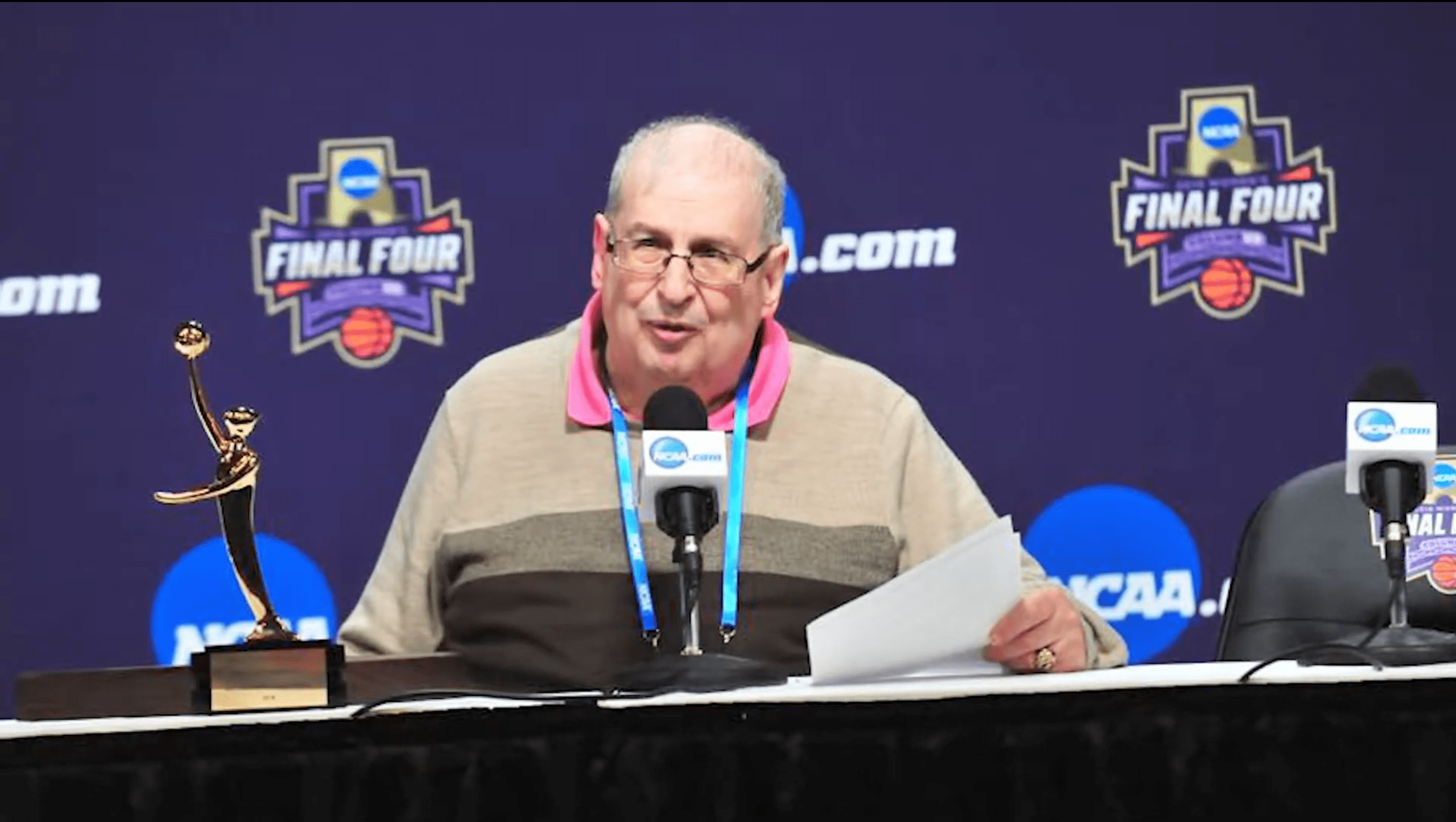

When Greenberg, 74, accepts the Hall's Curt Gowdy Award—a sort of lifetime achievement award given to basketball writers and broadcasters—in Springfield on Saturday, he will be the first women's basketball writer to receive it. In 2010, Greenberg retired from the Philadelphia Inquirer, where he spent 40 years as the paper's "women's hoops guru," chronicling the sport's rise from niche origins to something worthy of its own American professional league.

As a local beat guy, Greenberg, a Temple graduate, covered the glory years at Immaculata; Vivian Stringer's taking the reins at Rutgers; and more or less the entire basketball career of Philadelphia native Dawn Staley, from her high school playing days at Dobbins Tech to her years on the sideline at Temple, which she left for South Carolina in 2012. (Greenberg was first to break the news of her departure.) Their careers have felt somewhat intertwined: When Staley was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2012, she thanked the sportswriter in her speech. And when a ballot went out to WNBA writers this summer asking them to select the 25 best players in WNBA history from a shortlist for the league's 25th anniversary, Greenberg's first call was to Ron (Howard, the WNBA's director of communications) to ask why Dawn wasn't on it. (The answer was that she hadn't met the requisite number of awards criteria to be eligible. The former Ole Miss and Houston Comets coach Van Chancellor called Greenberg to grumble about this.)

Greenberg's primary claim to fame in women's basketball, though, is that he's responsible for launching the first women's college basketball poll in the country, back in 1976, when he worked as a clerk for the Inquirer. "I don't know who's had more firsts, me or George Washington," Greenberg said. "But I know I've crossed the Delaware to get to Trenton more times than him."

The women's poll was a suggestion of Jay Searcy's, the Inquirer's new sports editor at the time and a native of Tennessee—so, "one of Pat's (Summitt, the late Tennessee head coach, though I think you should know this one) mafia," Greenberg said. Searcy, who had written a women's sports column in his previous role at the New York Times and saw a flourishing sport, floated the idea to Greenberg, but given the dominance of just a few programs in women's basketball, Greenberg told Searcy he thought the idea was nuts. Greenberg had little say in the matter; soon, he was wrangling coaches into the new project. “Suddenly women’s intercollegiate basketball is more than an afternoon secret in a hidden gymnasium," he wrote in his column introducing the poll. "Overnight it’s more than Immaculata and Delta State. Now it means scholarships and Olympic medals.”

The results he'd tabulate, often at strange hours, on a Radio Shack TRS-80 computer, using a program that carried codes for different teams, matched everyone's rankings to point values, and could spit out a final list. Greenberg jokes that he and the poll are responsible for half the jobs in women's basketball, but it's not much of a joke. His creation of something prestigious to aspire to led schools to pay more attention to the state of their women's programs. "I am particularly happy that his name will be immortalized alongside the best to play and coach in this game, because he is a major reason women's basketball is where it is today," said Rutgers head coach Vivian Stringer in an email. Cracking the Top 25 inevitably brought less-storied teams some welcome local and national media attention, too. Some of Greenberg's favorite memories from his time running the poll—it's now run by the Associated Press—are calling athletic department staffers to give them a heads-up about their team's first Top 25 appearance and to let them know to expect a few more people at the next press conference.

What Mel brought to women’s basketball is something a generation of fans might take for granted now: basic professionalism, the simple means of measurement and comparison that make following a sport rewarding and, in the narrative sense, interesting. The poll plays kingmaker, forecaster, agenda-setter, rivalry-establisher. It sparks conversation. It illustrates decline—Greenberg remembers scrambling to consult his poll history database when Tennessee fell from the Top 25 in 2016, ending a historic 565-week streak. It announces the exciting, hopeful arrival of less-established contenders each season. And in February, it assured me that No. 1 South Carolina against No. 2 UConn would be a very good game to watch. Which it was.

If there's something Greenberg has done best in his career, it is just showing up and caring. "He'll show up for a 7:00 game at 3:30," said Cindy Griffin, the head coach at St. Joseph's. Ed LeFurge, a sports information director at St. Joe's who did play-by-play for women's basketball games when he was a student at Temple, remembers Greenberg being the only media member consistently there. On rides to and from games with Greenberg over the years, LeFurge has been regularly treated to the writer's stories. "Everywhere we go, he knows a story about the coach or one of the players or the history of the program," LeFurge said. "There's no other way to say it than he knows everything."

That skill—just knowing everything—is what makes him, as Stringer put it, "the best in the business." There isn't a whiff of cheerleading or advocacy to the way Greenberg writes and talks about the women’s game—you never get the sense of a women's basketball inferiority complex, that he feels the sport has anything to prove. All that's there is the diligence of an old-school newspaperman, given a beat to cover and ready to cover it. “The highest compliment that I can pay it is to treat it as sports, like I would anything else,” said Jonathan Tannenwald, an Inquirer soccer reporter who considers Greenberg a mentor and confidant. “And I learned that from Mel.” Greenberg is admirably secure in the importance of his world. I liked that he felt comfortable rattling off names of fairly minor women's hoops celebrities without much introduction, but called the Eagles, quaintly, "the local NFL team here."

When we spoke last month, for about four hours one afternoon, Greenberg had the giddy air of someone planning their own wedding. As he recounted his last few hectic weeks of seating charts and guests joining him at the Hall of Fame ceremony and various coded lists, he even made the wedding comparison himself. "Not that I've ever had to be involved in that directly," he said with a chuckle. He expects to see a sizable Philly contingent in Springfield this weekend, given that one of the inductees is Villanova's Jay Wright. The attendance updates trickled in while we talked; Phil (Martelli, formerly the men's head coach at St. Joe's, now an assistant at Michigan) would not be there, one text message informed him. Griffin can't be in Springfield this weekend either but she's promised to take him to dinner to celebrate soon. "Mel likes his free meals," she said.

After some friends ran an unsuccessful campaign to nominate Greenberg for the Gowdy Award in 2006, he had resigned himself to never winning it. "Palmer never won the PGA," he said. "That was his missing major. I said, 'The Gowdy's going to be my PGA.'" I was amused, at first, that Greenberg didn't affect the kind of false modesty or indifference expected of journalists in these situations. But I reminded myself that women's sports coverage demands some degree of constant self-promotion. Too often, the work doesn't get to speak for itself.

Just about everyone I asked in women's basketball used the word "legend" to describe Greenberg, but many of his actual colleagues at the Inquirer were oblivious to what he did while he was there. Once, Greenberg and the poll were profiled in Editor & Publisher and a few newsroom higher-ups were surprised to see Greenberg had gotten the Inquirer such good press when they stumbled upon the feature. "Nobody at the Inquirer knew him for a long time," said Tannenwald. "Even when he went into the Big Five Hall of Fame in 1992. Even when he went into the Women's Basketball Hall of Fame in 2007. I think there were some people in our newsroom who said, 'Wow, didn't realize he was that big a deal.'"

For a while, women's basketball coverage was technically something he did in addition to his eclectic clerk duties, which included retyping wire stories and driving the paper's Pulitzer Prize submissions to New York. In thriftier years for the paper, Greenberg paid for trips to cover the Final Four out of his own pocket. He described his celebrity to me using the analogy of a local baseball game, blacked out in his home market but available to stream everywhere else. (Later, I'd see this joke again on Greenberg's blog, in a roundup of lines he'd decided to cut from his Hall speech for time. Another was, "One day they asked me to show a young sports hire from Brooklyn around the office because they figured l had notoriety. Still, if you think l’m going to take credit for launching Stephen A. Smith, someone else can claim that.")

The joke aside, Greenberg says "making things easier" for the people who come after him is deeply important to him. "Not a lot of people realize how many people over the course of his career he has mentored and sent off into journalism, taught how to cover the sport, brought them inside the ropes, introduced them to people," said Tannenwald. "And that's not something you have to care about in this business. He chooses to."

Early in Greenberg's career, he found himself acting as a war correspondent of sorts, covering women's basketball's formative fight in 1980: the one between the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW), which had governed women's college sports and championships since Title IX, and the NCAA, which swooped in and took over. The tensions that animated the fight have hardly disappeared. A few weeks before we spoke, a report commissioned by the NCAA found disparities between its men's and women's basketball tournaments, exactly what AIAW advocates had feared would be the consequence of ceding women's basketball to a group for whom it wasn't a priority. Greenberg heard from the NCAA that he would be interviewed by the group putting together the report. He says he might have told them about an NCAA official telling him at the tournament this year that a more robust photo service cost too much money for the women's tournament, but the law firm didn't end up calling him.

It was hard not to feel a little optimistic as the conversation drifted, inevitably, to the great basketball he sees each year. He went back through the names. Kim (Mulkey, polarizing head coach at LSU. "We're kind of friends, even though, if you want to say something, I'm not going to argue you.") Marianne (Stanley, champion at Immaculata and head coach of the Indiana Fever. "Used to always say, 'plays like a Philly guard.' She'd be crawling all over the court, getting her knee skinned.") Diana (Taurasi, 10-time WNBA All-Star. "My tormentor! I don't mean that at all as a negative.") Aliyah (Boston, elite center at South Carolina. "A big star.") Paige (Bueckers, last year's UConn freshman sensation. "That was amazing how much extra writing I had to do last winter, on her just breaking precedent after precedent after precedent.") We could have remembered gals all evening.