A small part of what sucks about getting old is that rarely a day passes without someone dying whose deeds remind you of your own youthful aspirations. The rest of it is realizing that all those commercials for medications that help ameliorate diseases you didn't know you had are all about you because you're too stupid to know that everything is killing you.

Thus it was when news broke that Robbie Robertson, the core of the seminal late-’60s/mid-’70s band eponymously known as The Band, passed at age 80. Eighty? Yeah. Eighty. One of your idols when you were a youth did eight the hard way, so you know what that means, right? Of course you do.

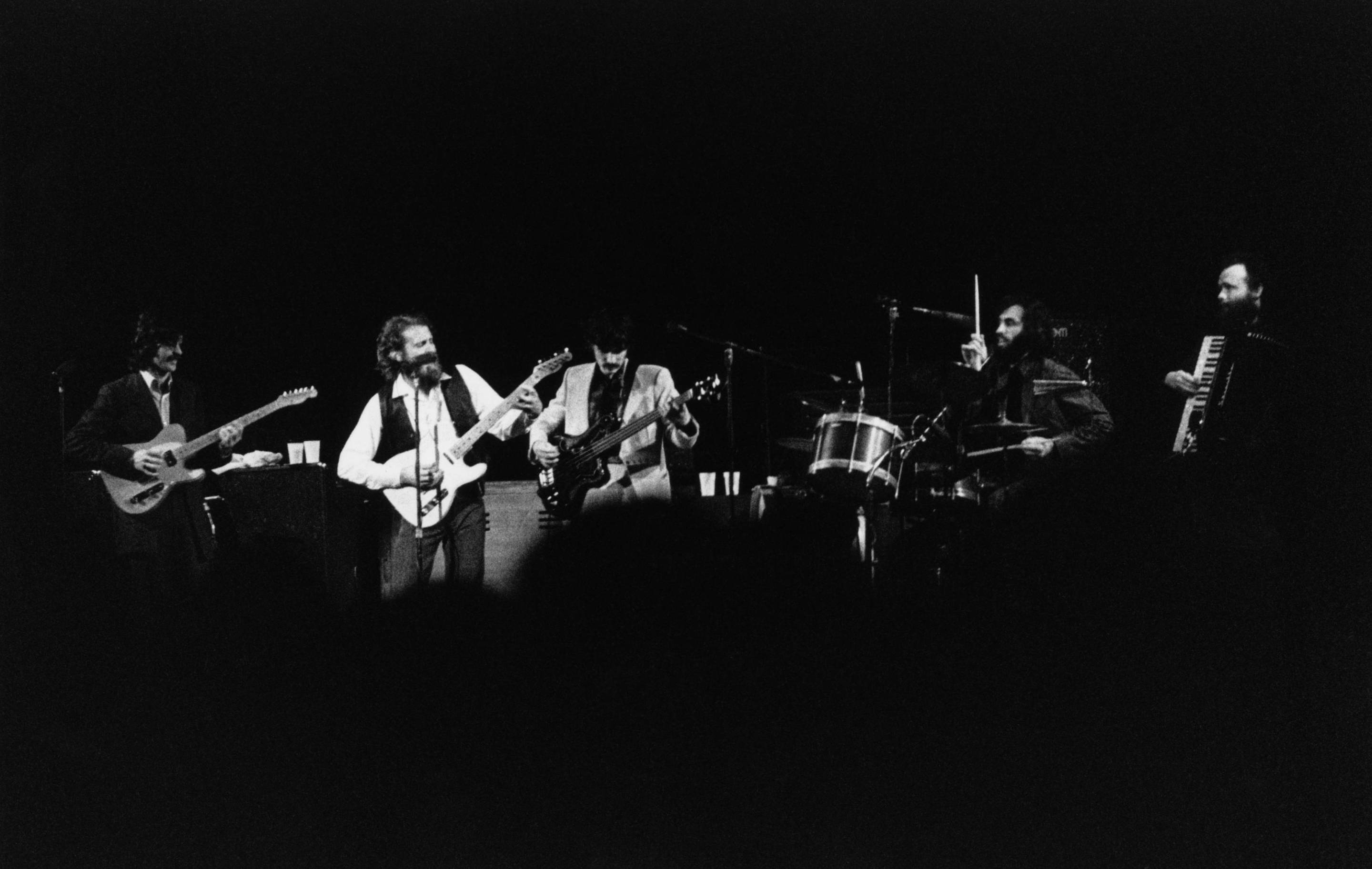

Robertson was the band's lead guitarist, principal songwriter, and principal guide through their eight-year span as the favorite group of music critics everywhere. They zigged when rock music zagged by finding cultural commonalities in a country already defined by its differences; they tied themselves to one of the defining figures of the age in Bob Dylan; created their own genre; captured their own essence in The Last Waltz, in which they allowed Martin Scorsese to help them celebrate themselves in a weirdly admirable but truly self-flattering way; and burned themselves out, all in eight years. They were cool by being uncool, and now with Robertson's death they are down to one surviving original member in keyboardist Garth Hudson.

And it is Hudson rather than Robertson whom we focus on here, not because he remains punching the clock at age 86 but because he was the most accomplished musician not only of the band he was in but perhaps in all of rock history. He played every conceivable keyboard including the accordion, though he was a master on the now anachronistic Lowrey organ, and he played nearly every conceivable woodwind, and sat behind Robertson, pianist Richard Manuel, bassist Rick Danko, and drummer Levon Helm as the musicians' musician, never singing a note but guiding the group's melodic heart by knowing more about the subject than anyone else. Indeed, he joined the band only after convincing his reluctant parents that he was also going to be the group's music teacher—that's how much game he had in a band full of game. He was part Svengali, part Erich von Stroheim, the silent owl in a world only he could see completely but one in which he knew his bandmates would follow.

And we use the past tense of the verb only because the band is gone, not him. He was the ideal musician for people who loved music but distrusted frontmen, because all frontmen have a disturbing level of preen to them. He was one of the very few who led without anyone knowing they were, probably because they sensed that the coolest kind of cool was the one that never revealed itself.

It's hard to explain 50-year-old music to 30-year-olds without video guides, though finding The Band's full discography isn't difficult. You can see them in your minds' eyes by finding The Basement Tapes, the most bootlegged bootleg album ever, and their showmanship could be found in their lack thereof. They took a stage, they played the most intricate songs...

…then they took their bows and went home. They built an ethos out of being the adults in a kids' game, and Hudson was the most adult of them all by virtue of being the oldest, knowing the most, and being whatever you call the glue guy in a musical group. You could barely see him in a live show (The Last Waltz is largely a cinematic tour of the top of his head) because he didn't need to be seen, but he had to be heard for the song being played to have any gravity. Even now, five decades later, there may not be a comp for him in all of contemporary music.

In any event, his will be the last obituary written for a band that could have only existed in the time it did; “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” is probably problematic today when taken from its original context as a lament for a beaten Confederate soldier, and “Shootout In Chinatown” is a forgettable cliche, but most of the catalog is worth cherishing as long as you're willing to consider that there was music before your birth. We totally get it if you don't want to make that concession, because all music is generational, except Motown.

This was just a notation for Garth Hudson, who easily beat the actuarial tables while seeing all the good and bad of an industry that often flew into the sun in pursuit of the warmth of genius. His last appearance on stage was barely four months ago backing Sarah Perrotta at her Flower Hill House concert, so he is a badass among badasses just on that alone. So for all you may read about Robertson in the next few days, the story that transcends is Hudson’s—the giant who made sure you could only imagine his shadow, because he worked in the spaces where the lights didn't shine.