ALL OVER NEWFOUNDLAND — Martin Pond had just finished the flight back to the West Coast from the easternmost of East Coasts when his wife and logistical supervisor Julie showed him a text message. He read it and broke out first into a wide smile and then a prolonged, profound laugh. It was at that moment that the saga of The Brown Smear In Newfoundland took one final, surprising, and oddly rewarding turn. For purposes of foreshadowing, this meant one final spin around a long and twisted track with narrow and uneven roads.

Some stories tell themselves with a single pitch to the editor, who then has to approve the budget; from there, those stories adhere tightly to that from reporting through final product. Others morph slowly into something else as events dictate. A few go from mere narrative to character study.

The story of the Smear, on the other hand, was a bit of a hot mess, pun entirely intended. It took multiple forms over the course of the week because it was almost and already too many things, for too many reasons. It needed a unifying moment, if something as stupefyingly mundane as receiving a text message can be so glorified. But you take what you get in this game, and the only recourse you really have in the end is to wait for the sound of God looking at you like the moron you are, before laughing at your feeble attempts at making plans.

This story that came from your author attending the Targa Newfoundland, a weeklong rally race covering 1,400 miles, could have easily been solely about the Brown Smear itself—a 1980 Mercury Zephyr station wagon with paint that suggested the interior of a baby's diaper. In its original form, it looked like the kind of car a parent buys because the family's other vacations were marred by the kids in the backseat being close enough to have their whining heard. In this story, it becomes a race car.

But we're already ahead of ourselves. A car is just a car without its owner, who in this story is Martin Pond, a mechanic and car savant who can take a mundane piece of metal and make it perform like the bigger kids' Porsches. The Zephyr was one of those triumphs—a shell he bought for $500 at a junkyard and turned into not just a usable car but one that could be driven fast and skillfully around local tracks. He sold it before the 2018 Targa Newfoundland, taking instead a 1980 silver Ford Fairmont last owned by your great aunt Thelma. But sometime during that race his co-pilot and partner Chris Seiwald said, "You know what would be fun? Doing this with the wagon.”

Fortune smiled when the person to whom he’d sold the Zephyr offered to swap it back for a Ford Durango that Pond had modified for racing before the rules for that particular kind of driving were changed to require greater weight, making his modifications useless—plus a trailer to be named later. So the fateful bargain was struck. As Pond said, "I don't know if Chris would have wanted to do this again without the wagon."

Pond had the will to race Newfoundland in 2018, but he needed organizational muscle and financial backing. To get the first, he had to sell the idea to his wife Julie. She was skeptical, but her gift for organization of both family matters and more complicated projects like dinners for hundreds and open fundraising powered her curiosity. Had she had Winston Churchill's job in 1939, World War II would have lasted 16 days, England would have won the deed to Europe, and the History Channel would never have gotten off the ground. In this life, after some hesitation centering on all the reasons why this was clearly an idiot's quest, she opted in.

But to pay for this indulgence, Pond required Chris Seiwald, a retired software company owner who had sold his business nearly a decade ago; he’d split roughly half the proceeds among his own employees, making many of them millionaires. Pond took Seiwald to lunch and made his pitch to fund the Newfoundland trip, which included a role for Seiwald in the car as navigator. After a week and several conversations with Julie to work through the logistics, Seiwald said, "Let's make this happen."

Seiwald is a ball of exposed nerve endings with feet, an adventure-seeker who has driven motorcycles across the United States, through India, China, and South America. He’s a regular attendee at Burning Man, and before this year's festival spent a month in Australia and New Zealand watching the Women's World Cup. Seiwald's wife Trudi has her own callings, including climbing the tallest mountain on every continent—Everest, Denali, Aconcagua, Vinson, Mont Blanc, Kilimanjaro, and Kosciuszko—as well as Machu Picchu and Puncak Jaya just for kicks. She has skied the South Pole and wants to ski the North Pole. In her off time she raised six children to productive adulthood, the pitiable slacker.

So in 2018 they went to Newfoundland in the Ford Fairmont, came within three seconds of winning the class (timed racing over six days and multiple legs), and won a number of admirers within the racing community and among local onlookers. There is a level of inside-the-ropes cred that goes to racing drivers driving not-racing cars, and the Fairmont made Pond something of a pit-row legend, if parking on the side of a neighborhood street and shooting the breeze with your competitors between runs can be called pit row. But the Fairmont’s lore would pale in comparison to the legend of the Brown Smear.

But we're not ready for that yet. The question of "Why Newfoundland?" must be addressed.

The answer begins with the time zone, which is 90 minutes ahead of Eastern time and a half-hour ahead of Atlantic. This is a perfectly reasonable notion to residents but a math-in-your-head inconvenience for visitors. Subtracting four-and-a-half hours to figure what time to safely call home is never not obnoxious. They even tried a double-daylight-savings gambit one year, turning their clocks ahead two hours to see how close to Iceland they could get, but that proved too dark in the mornings for most of the citizenry and the experiment was abandoned. But precedent for genially contrarian living survived even through the province waiting until 1949 to join the Canadian dominion. Before that, they were part of Hobbiton, for all we know.

The people that live here apply three general rules on outworlders. One, it's "NewfoundLAND" as in "underSTAND," not "Newfundlund" as in "My mouth is full of oatmeal." Two, the inhabitants are not, are never "Newfies." Dogs can be, but not the people. And three, they are not to be grouped alongside Canada’s three Maritime Provinces, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick. When it comes to drawing lines between their world and the one in which everyone else lives, the people of Newfoundland and Labrador are as serious as an unexplained lump.

The island leads with predominantly Irish influences, but soon breaks out into chunks of the English, Scottish, and French. The farther in you get, the more tortured the dialects, with a recognizable word surrounded by a series of things without vowels that outsiders can only guess are also words. As Tom Pokorny, a Torontonian and part of the event's social media team, put it to me, "It's kind of a little bit like Appalachia, except that when they tell you what's on their mind they're really nice about it." From experiences during race week, “nice” includes allowing strangers to use their home bathrooms in moments of lavatorial emergency and, in one case, offering the bathroom-user a beer on the way out.

Newfoundland has only three official cities, St. John's, Mount Pearl, and Corner Brook; its most famous municipality is none of those. That would be Gander, whose citizens hosted 6,000-some-odd stranded air travelers diverted from the sky on 9/11 and so inspired the musical Come From Away. Newfoundland’s second-most famous town, Dildo, is the centerpiece of a cottage industry, which is cartographers who name towns and bodies of water like they were 11-year-old boys at a sleepaway camp. Dildo is ostensibly named for a part of an oarlock, or could theoretically be a bastardization of "doldrums," but those explanations are not what convince tourists to go there and buy sweatshirts, hats, and beer, nor what gets Sandi Toksvig's attention. There are plenty of proper names on the island that exist at the juncture of Mad Lib and PornHub. A non-exhaustive list would include Conception Bay, Squid Tickle (now known as Burnside after a fire that took out half the town), Leading Tickles, Come By Chance, Happy Adventure, Witless Bay, and Spread Eagle Bay. Draw your own conclusions, by all means, but keep them to yourselves.

Newfoundland is politely yet defiantly its own place, so it makes some strained bit of sense that it chose to start North America's only tarmac (street roads) rally race in 2002. Off-road rallies require less bureaucracy and have fewer restrictions, but as the Newfoundland race runs through towns in which actual people live and vote, it requires much greater buy-in from governments, people, and volunteers. This makes it more difficult to organize and maintain, and after COVID-19 caused the postponement of the race, it took years to reassemble it in a way that all of its constituent parties could accept.

Of course, COVID took out most pastimes in 2020; Pond had shipped his car to Australia for entry in Targa Tasmania, only to see it canceled while the car was on its way across the Pacific. The race resumed in 2021, but four deaths in two years, plus a jurisdictional fight between Targa Tasmania and Motorsports Australia, caused the 2023 race to be canceled in the wake of a 15-month safety review. Allowable speeds had been lowered as part of a recommendation for greater safety by Motorsports Australia, which led to an 80 percent drop in entrants; the two sides have not reconciled. In short, these are days of retrenchment for rally racing.

At this point, we hear you asking, "Are we there yet?" We can only say, "We're getting there, you little creeps. Pipe down."

The Newfoundland race went from approximately 40 entrants in 2018 to under half that in 2023, and it took a bit of cajoling from race organizer John Hume of Hume Media in Toronto to attempt a Hail Mary—getting famed racer Randy Pobst to enter. Hume even promised Pobst his seat in his car, giving up one of his most cherished pastimes in an attempt to save it.

Pobst, 66, has won more than 90 races in his career, and set a world speed record for an electric vehicle in the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb. Because he also mixes driving with writing about motorsports, he is one of the scene's most notable and attractive names. He is factory-supported by Porsche, Audi, Volvo, and Mazda simultaneously. Wikipedia describes him as a vegetarian and his silhouette strongly suggests that of a sandtrap rake, but off a week's evidence, his rail-like profile mildly belies the fact he would happily exist entirely on desserts. At a locally provided lunch on one of the racing days here he worked effortlessly through three slices of pie without downshifting once. Putting it bluntly, Pobst was one of Pond's driving idols before this race, and greatly enhanced his standing during it, one lemon meringue at a time.

Another notable name in the race (though she politely disputed this when asked) was Leanne Junnila, a Canadian who works at the University of Calgary in research infrastructure design, has one master’s and is working on a second, has been a racer for 20 years, and has founded and leads the nonprofit Women In Motorsports Canada in her ongoing attempt to fight the malady of free time.

"I was very shy as a kid, and I pretty much kept to myself because I wasn't comfortable talking to people," she said. "I don't honestly know how I could have so little confidence in myself, but I got my driver's license and my experience was that the license process is more about safety, and that they don't teach you to drive as much as they teach you to park. So I went to a rally school." She eventually signed a two-year contract with Team O'Neil, pursuing a passion she never thought she had in avenues she never thought could exist for her. She has pursued greater avenues for other women in motorsports ever since.

She was co-piloting a fully caged Ford Fiesta with (rather than “for,” as navigators are true equals to drivers in rallying) Dave Wallingford in a race in Mexico in 2019 when the car hit a washout on a corner and flipped three times. She walked away unharmed ("I just needed a little ice for my neck") but Wallingford was stuck hanging upside down in the car for an hour, broke his back, underwent surgery, spent a month in hospital, and took a year to re-learn how to walk. When asked how the accident might have tempered her enthusiasm, Junnila said quickly, "I wanted to get back in a car the next day."

The other cars had their own stories. Edison Wiltshire, a Newfoundland regular known by his windshield as The Faster Pastor, employed his granddaughter Olivia as his navigator. Husband-and-wife team Satish Gopalkrishnan and Savera D’Souza, Pond's only competitors in the Grand Touring division for timed racing (hitting specific places in specific times), were driving a Mercedes SUV—well, Gopalkrishnan was driving. D'Souza doesn't drive, anywhere, even at home, she said. Pokorny and driver Corey Finkelstein entered a rental car and slapped a few stickers on it including one of a toque with the legend "Eh! Team" to make it look more Canadian and less Hertz-y.

And then, at long last, there was the Brown Smear.

The Smear was so named by Seiwald because “Brown Blur” would be giving the car too much credit. Rally racing is peculiar in that competitors have more respect for cars that don't look raceworthy but are, and the Smear looked less like a race car than anything else anyone had seen. The Smear had been chosen by other drivers as the car most likely to break, blow the engine, or run off the road, but Pond's credibility had been established with the Fairmont five years earlier and the Smear was basically just the next stage in motoring anti-evolution. "That car is amazing, if you know what you're looking at," Junnila said in admiration of the Smear. "It's an absolute beast. It's definitely the coolest car here."

That is an admission that underpins the general feeling among drivers toward their competitors, especially in events that don't offer prize money. Everyone gathers before every stage and just hangs out as if they were all on the same team. Relationships are made, friendships forged, and one means all. When the Porsche driven by Steve Davies and Wayne Lorenzen skidded into a marsh on the final day, fellow drivers Sam and Rick Marshall stopped and helped pull the car back onto the road, where it and they finished the race. Pond had two suspension bolts break in 2018 and was helped almost immediately by other competitors because, while winning is the goal, beating everyone else when they're running properly means even more. “Maybe it’s just the shared notion of danger in extreme sports that makes people more willing to help each other,” Junnila suggested.

"It really is the relationships that matter here," Pond said. "It's the thing I care about most, and the thing I'll miss the most when this is over." It also helps that Julie Pond's sixth job after paperwork, bill paying, travel, housing, and attention to procedural detail was talking to every single Newfoundlander, living, dead, or undecided. For her, there are no strangers, only people she hasn't bothered yet. She spent five minutes persuading a baggage security person at the airport to follow their racing team account on Instagram—this, after the race had been over for three days, when following the team for any reason was essentially pointless.

The Smear also caught Pobst's gaze, and he politely but repeatedly hinted between trips to Dairy Queen that he would love to drive it at some point, a bold request to make given the territorial nature of driver/car relationships. Martin, Julie, and their son Martin Jr. were the only ones ever to have driven the car—even Seiwald was shotgun-only. The most contact anyone got with the Smear was visual, and at the end of every day the cars would go to a local dealership for townspeople to gawk at up close. Between stages, people in neighborhoods would come up to cars and ask what was going on because somehow they hadn't been notified the race existed; inevitably, after a few incredulous exclamations of "No shit!"—the Newfoundlandian reflex for all forms of surprise—they walked away satisfied. This was out-of-the-ordinary stuff in a lot of deeply ordinary towns, and for the most part novelty trumped nuisance. There was a rumor that a disgruntled local had parked his loader in the middle of a street to block the racers from driving through his neighborhood, but as Pokorny, a true believer, said, "Nobody ever saw it. Me, I don't think it happened."

Even the car's sponsor stickers caught the eye, and not only because they surpassed the car's Blue Book value. They were not strictly automotive. There were stickers for the Alameda International Film Festival, a local ice cream parlor, a plumbing service, an as-yet-nonexistent performing arts center Seiwald is helping to build, an insurance agent, a funeral home, and finally there was this:

Not that a company as grim as that would actually contribute money, mind you, but someone had to mind the front of the car in those tight turns on Random Island (another actual Newfoundland name), and we put our best man on it.

It was part of Team Smear's massive media strategy, the other prong of which was provided by filmmakers Joe and Phil Matarrese, friends of long standing. After the 2018 race, they heard over Thanksgiving dinner at the in-laws' about the experience and decided that there was at the very least a documentary and maybe even a movie in the Targa Newfoundland. They started interviews before the 2020 race was canceled but never abandoned the project because, as Phil Matarrese said, "Everything is a story. It's just about whether you can execute it." Then again, they describe their style of filmmaking as "dark altruism," so who the hell knows what they're on about.

There have been plenty of Targa Newfoundland documentaries over the years, so nobody seemed all that surprised to see moviemakers bopping around Turk's Gut or Petley. The hook here was clearly The Brown Smear, with the added color (so to speak) of the race having been up on blocks for a while. The Matarreses invaded air space with a drone, loaded the Smear with GoPros and 360-degree cameras, and put mics on both Pond and Seiwald to capture moments like Seiwald urging Pond to make a right turn by saying, "Righteroo." Max Verstappen has never said “righteroo” in any context, if that helps.

The race began early on a Saturday once it became clear that Hurricane Lee would spend the last of its energies in Nova Scotia, and immediately the rust of organizational inactivity revealed itself. Whole legs of the race were canceled, shortened, or otherwise modified, starts were delayed, and often there weren't enough volunteers to crime-scene tape off corners or driveways along the various courses. There was an almost hourly scramble to keep the race on a semblance of order, and some legs were less suited than others. At the Bare Mountain Coffee House in Clarenville, the proprietor came out to look at the Smear in admiration, then asked where the next leg was, and said of the answer, "Oh, that road is shit." In fairness, it was.

Eventually the race found its true north, but sitting in a park in Fox Harbour after lunch on Day 3, Pond worried about its future. "The costs for things like this are just going up all over the place," he said. "Insurance, protestors, the cost of getting your car here … I mean, I love it, the people here are very kind and conscientious, and I've made friends I could never have known otherwise. This is the reason I came back here, and it cost a lot in time and money to do it but it was all worth it. I hope it stays and gets back to the size it was the last time we were here, but you never know. Look at Tasmania. Plus, I'm not getting any younger [he is 62] and right now I'm pretty exhausted. This could be the last of these for me, or maybe anywhere."

But by the end of the week, people were talking about "next year" as a fait accompli. Dates for next September were set, coupons given out at the end-of-race dinner for next year’s entry fee. People believed because they want to believe, and the damp gloom of the early stages had been replaced by optimism's flame. It's not necessarily a happy ending yet, but it's the ending we have at press time. Remember how God likes to examine your work before setting it on fire.

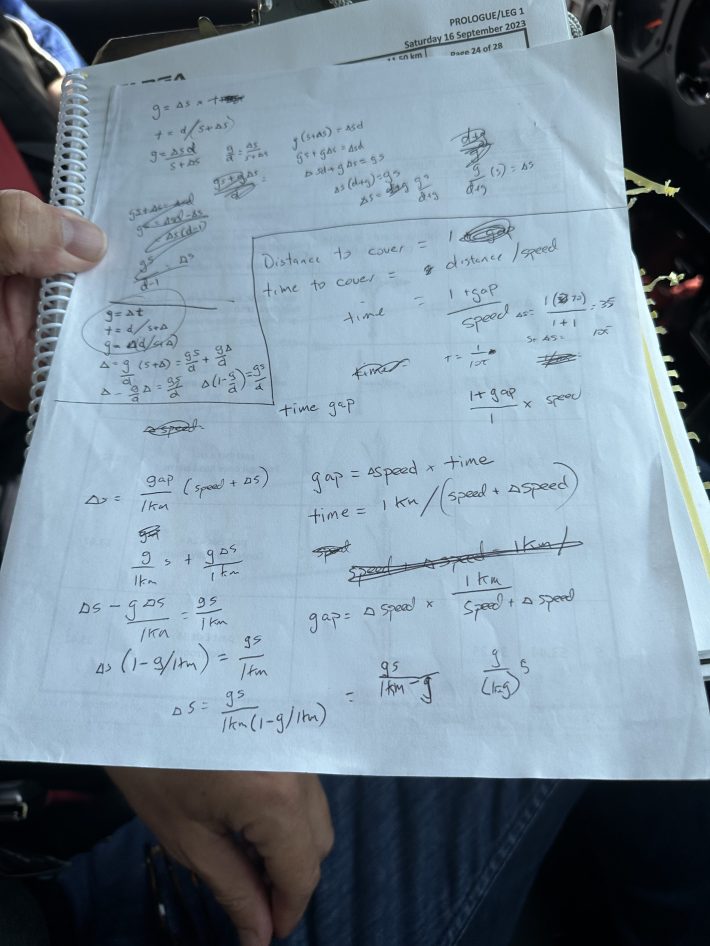

And for those of you who have stuck with your author’s meandering rally of a feature, we bring you the race itself, and finally the text message that explains it all. Seiwald spent his pre-race prep devoted to creating rubrics to help with the navigation calls in the car, or as he described it, "doing fifth-grade math to find a repeatable formula that will be OK for short runs and long ones." In other words, this:

He also found time to feed his new addiction: morning mochas. Mere coffee wouldn't do, and he only begrudgingly acceded to one dose of Tim Horton's finest. He was almost wistful, in fact, when next to one Jumping Bean outlet he found an Oceanic Cannabis shop, which sparked a discussion about his version of "nature's perfect meal—a sugared (not corn-syruped) Dr Pepper, Ritz Crackers, and an edible." The Dr Pepper and Ritz were located and consumed, but he eschewed the edible. He even had to care not to overserve himself at the gin-and-tonic way stations (we call them restaurants) on the tour because of the morning breathalyzer.

Day 1 was uneventful, but disaster arose on Day 2 when Seiwald was trying to reset a display on his battery of timers and accidentally turned off the device when the car hit a bump and jostled his hand into error. He scrambled to recalibrate but lost his place in the rally book (a daily map of all the turns on the course) and eventually had to concede to Pond, "I can't find where we are. You're just going to have to drive it."

"I don't think he ever got completely over it," Pond said later, "but I tried to tell him I was totally fine either way. It meant we could pretend to race in two classes instead of one."

As it turns out, Pond has always wanted to do without the child seat of time restraints. "Martin likes to drive fast," Seiwald recounted later, acknowledging in his quick-paced and semi-adenoidal voice that his skill is on the timing and navigation side, while Martin plays the pedals. Pond happily acquiesced to driving the less restrictive side so that Seiwald could be more involved in the actual competitive racing, but having lost the early advantage to Gopalkrishnan and D'Souza their chances of winning had been greatly diminished, and after Day 3 those chances were all heads in freezers and corpses in walls. Gopalkrishnan and D'Souza had driven rallies in India and the States and were quite formidable, so as Pond said on Day 3, "We're totally out of this unless something catastrophic happens, and they're too good for that."

Thus, a new strategy: one timed run to get as close to zero as possible for Seiwald's satisfaction—as the goal in rally driving is to avoid rather than amass points—and the rest were the-hell-with-it runs. The first, the perfection run, to show that they were just as skilled a team as they had shown in 2018 and that Seiwald had actually found the formula he sought, and the others to let Pond pretend he was actually racing in the less time-restrictive class.

Thus unshackled from their competitive sides, Pond and Seiwald defined the race on their terms rather than those of the rally monitors, which is to say they weren't outwardly rude about the rules or unpleasant to their enforcers, but were at best casually mindful of either. They even passed Gopalkrishnan and D'Souza on the road once, which if both were adhering to the rally book would never happen. This caused a momentary shouter between Gopalkrishnan and D'Souza trying to figure out how they could have screwed up so badly until they realized the screw-up wasn't theirs at all. "You caused us to have quite the argument," D'Souza told Pond with a laugh after the run. "We didn't know how we could be that far off until the run ended, and then we realized it wasn't us, it was you."

"I didn't care at that point," Pond said of the defeat. "I was here to have fun, and I had a blast."

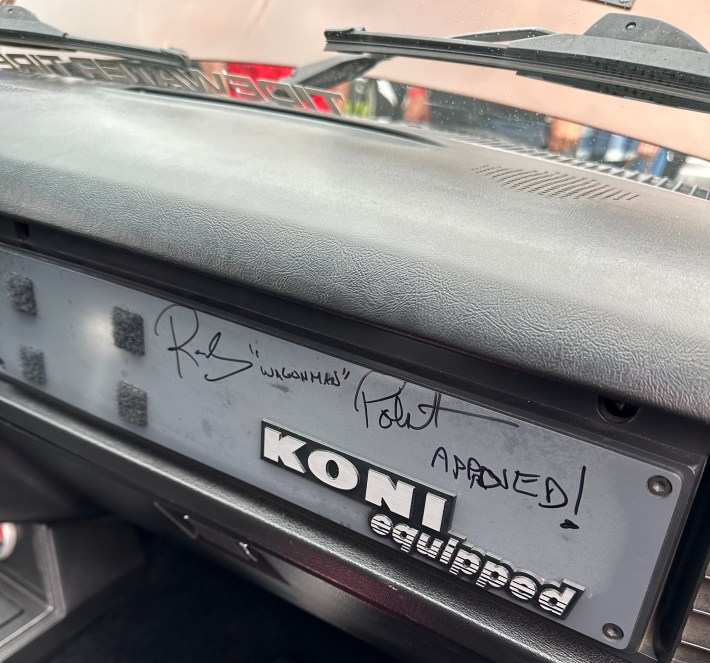

More maverick still, he even let Pobst drive the Smear for the last run of the day on Thursday in Brigus, and achieved his final goal of the entire week, getting Pobst to autograph his dashboard:

By race's end, Pond and Seiwald had finished second in a field of two, and Gopalkrishnan and D'Souza maintained their metronomic devotion to the greater goal. The week was over, Newfoundland had done its Newfoundlandy things, a growler from the Dildo Brewery had been purchased as a souvenir, the Brown Smear was trailered and sent back home with a coiled poop emoji as the graphic icon monitoring its progress, and there was merely the flight home left. And the text message that made it worth all those months of planning and prepping and primping and paying—to find how much reward there is in caring about things that can't be found in the brochure.

The text message itself was simple. It was a final totting up of the race details, a box score of their run as well as Gopalkrishnan-D'Souza's, that doesn't happen immediately after the end of race because of the time it takes to assemble the details for every car, stage, and time. Gopalkrishnan and D'Souza's score was a nearly perfect 17, a mathematical tip o' the crash helmet to their skill and experience.

And Pond-Seiwald's score was 408. Yes. Four hundred and eight. They were beaten by Gopalkrishnan and D'Souza by the equivalent of 24 full races. Pond-Seiwald's 2018 score had been a very commendable 38, which meant that they accumulated nearly 11 times as many penalty points using their new YOLO strategy.

Martin Pond laughed the laugh of a very satisfied fellow that morning outside the international terminal at SFO, and despite the entreaties of his wife to "give it a rest, we just got home," his thoughts ran immediately to how he could properly contextualize for his gearhead pals the worst and most glorious non-family-related event of his life. He’d lost to his competition by nearly a quarter century’s worth of Targas, and made friends with Randy Pobst, Leanne Junnila, and lots of other folks whom he would happily put the arm on Seiwald to see again. The Brown Smear had been a complete success from dog's face to gas tank: Pond is a folk hero to a very small group of folks 4,500 miles distant by car, and four and a half hours by clock. He was already mentally modifying the suspension and shock absorbers for a 2024 that may or may not come, because it was too soon to fear the worst but just early enough to plan for the best. Name a trophy that beats that.