The recent appearance on the Today Show of the three women who invented the sports bra was your typical morning-show fare: three-and-a-half-minutes of relentless cheer.

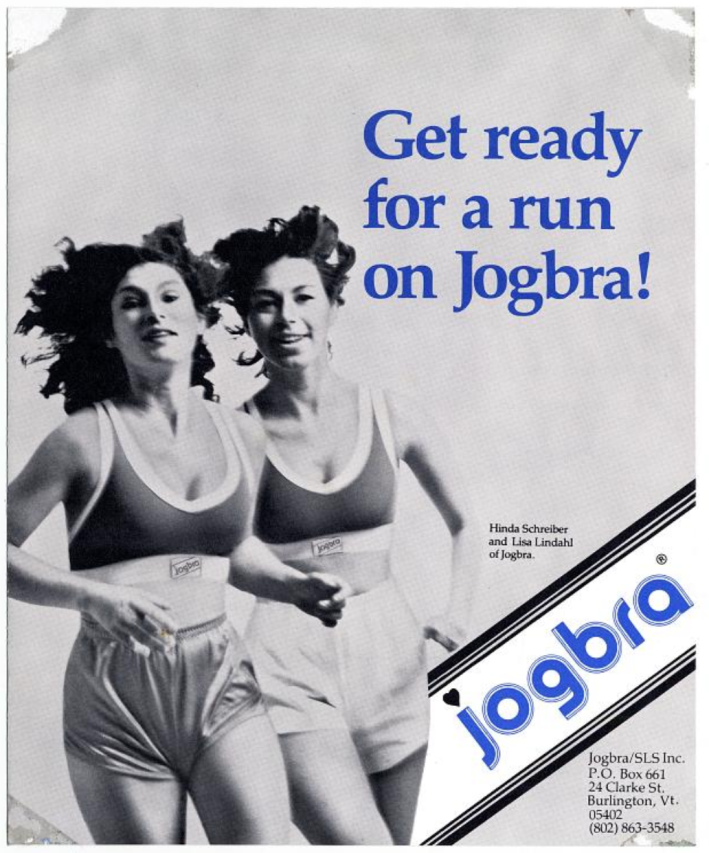

“Learn how three friends transformed the way women exercise forever,” the host gushed in the tease, before she Zoom-interviewed Lisa Lindahl, Polly Palmer Smith, and Hinda Miller from their respective homes.

And why not? The sports bra was a true innovation. In the wake of the passage of Title IX in June of 1972, the invention made it easier for millions of girls and women to play sports, and created a unique category of sportswear apparel that today is a multi-billion dollar industry. As Runner’s World magazine headlined its 2018 feature story: “The Greatest Invention in Running—EVER—Is the Sports Bra.”

Most media coverage the three women have received about their game-changing creation echoes this effusive, downright reverential tone. “Women Supporting Women: The Inspiring Story Behind One of the 20th Century’s Least-Appreciated Innovations,” is the headline of one representative example.

In her illuminating new book Let’s Get Physical: How Women Discovered Exercise and Reshaped the World, author Danielle Friedman detailed how the inventors overcame a “seemingly endless series of challenges” in bringing the sports bra to the marketplace, including the financing, legal and patent hurdles typical for any start-up, as well as the anachronistic attitudes of the male bankers and sporting-goods store owners they dealt with.

But never once did these or other contemporary accounts address what was perhaps the most significant barrier that the entrepreneurs faced: intra-office feuding that nearly undermined their nascent business, with accusations of betrayal and backstabbing that linger to this day. By the time they sold their company in 1990, Lisa Lindahl and Hinda Miller were so fed up with each other that they didn’t speak for more than a decade.

Erasing the strife from the creation story of the Jogbra, as it was called, has sanitized and simplified the narrative. Female empowerment in the post–Title IX era has become the default storyline—why ruin a plucky underdog yarn with dollops of angst and conflict? Why portray complicated, real women and their divergent drives and opinions when you can stick to the facile script and produce what Lisa describes as a “fluffy piece” about three bosom buddies?

In an era when young entrepreneurs have become fodder for countless movies and TV shows—cf. The Dropout, WeCrashed, and Super Pumped, to name just a few—eliding the true story of the women behind the sports bra is an omission and a diminishment that’s as remarkable as the sports bra itself, especially because the three women have no hesitation talking about the messier parts of their story.

The sports bra’s invention encompassed a peculiarly 1970s zeitgeist, mixing elements of the burgeoning jogging and fitness craze, the counterculture invasion of Vermont, Second Wave feminism, New Age philosophy, the acknowledgment of people with disabilities in sports, and a righteous dose of serendipity.

All involved agree that the original idea for the sports bra came from a recent transplant to Vermont named Eugénie Louise Zobian. Known by her nickname of Lisa, she was diagnosed with epilepsy at an early age, and didn’t participate in sports while she was growing up in Montclair, New Jersey. She moved to Vermont with her first husband, Al Lindahl.

“One of the things that was beaten into me growing up was, ‘You can’t be alone, you can’t be independent. If you ever have a convulsion while you’re alone, you could die,’” Lisa told me by phone from Charleston, South Carolina. “My answer to that was to find a husband. So, I married young.”

In the summer of 1977, Lisa was 28. She and Al were living in Burlington, part of an influx of young, largely white Baby Boomers who were transforming the Green Mountain State into the crunchy-groovy “People’s Republic of Vermont.” Think back-to-the-land communes, organic farming, and, yes, bra-burning. Think Bernie Sanders, who moved there from New York City in 1968 and was elected mayor of Burlington in 1981. Think Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield, who opened their first homemade ice cream shop in 1978 in a converted Burlington gas station.

Lisa was studying for her undergraduate degree at the University of Vermont and working part-time as a filing clerk, while realizing that “it was not a happy marriage. I was an emotional eater, and I was gaining weight and feeling very uncomfortable because I never had to deal with that before.”

A friend offered a solution: “Why don’t you start running? If you run just a mile and a quarter three times a week, that’ll get you in shape.”

If the 1950s saw the rise of leisure activities in suburbia, with bowling leagues, golf at the country club, and Pop Warner football, the 1960s planted the roots for what would become the exercise boom. Concerned about the “disturbing deficiencies in the physical fitness of American youth,” especially when compared with youngsters from the USSR, John F. Kennedy established the President’s Council on Physical Fitness shortly after his inauguration. Three years later, Surgeon General Luther Terry released a report that definitively linked tobacco use to cancer and other illnesses. In 1966, Dr. Kenneth Cooper coined the word “aerobics” and published a best-selling book about the benefits of exercise.

Jogging became the default activity, on the heels of Frank Shorter’s celebrity after his marathon triumph at the Munich Olympics (the first U.S. marathon gold medal since Johnny Hayes in 1908). Advances in sneaker cushioning from Blue Ribbon Sports (now known as Nike) and other companies attracted recreational runners, while Jim Fixx’s The Complete Book of Running remained on the bestseller list for more than a year. Olympian Jeff Galloway launched Phidippides, the first retail store dedicated to running, in Atlanta in 1973, and Fred Lebow dragged the New York City Marathon across five boroughs in 1976. Jimmy Carter took up jogging while he was in the White House, although his presidential image suffered when he collapsed during a 10k.

But women like Lisa Lindahl faced obstacles even before they laced up their newly minted Nike Lady Cortez sneakers. The ignorant thinking among sports officials was that female athletes couldn’t endure the rigors of truly strenuous physical exercise; up until 1976, the longest event for women runners at the Olympics was 1500 meters, or less than a mile.

Lisa wasn’t training to run a marathon. Still, the day she completed a mile around the tenth-of-a-mile indoor track at the University of Vermont, she felt “so wonderful. It was the equivalent of winning an Olympic medal to me. It was helping with my depression. It made me feel more independent. I said, ‘How far can I go?’”

Long runs through the Vermont woods, under the flowering chestnut trees, revived her spirits. “I’d always had a fraught relationship with my body because of epilepsy,” she said. “Until I started running, I was not intimate with my body. Running empowered me enough that I realized that I had to take some action around my marriage. The thought of divorce was scary because it would mean I’d be living alone, which I had never done and which I had been told not to do.”

Running was empowering, but the tradeoff was pain. Human breasts are made up of fat as well as glandular and connective tissue, blood vessels, and lymph nodes. Breasts have no muscle; the Cooper’s ligaments provide support and attach to the chest wall, but do little to reduce movement. During exercise, biomechanics clash with biology: Breasts move up and down, backward and forward, and also side to side, causing severe discomfort.

Existing bras were elaborate feats of engineering involving unwieldy clasps, hooks, underwire, and straps. Their main purpose was to push women’s breasts into a shape that looked attractive underneath dresses and blouses. Comfort was rarely considered in “women’s intimate apparel,” as the trades referred to it, but the male gaze certainly was.

Bras made exclusively for sports or exercise had never been produced. Women runners were forced to wear their everyday bras and suffer chafed skin and bleeding nipples. Some took to strapping on two bras to curtail movement even as they endured derogatory comments from men.

“My breasts were flopping all over the place,” Lisa remembered. “My bra straps would slip off my shoulders, and I was always pulling them up, and sometimes it would get very hot and sweaty under my breasts. I figured that was the price I had to pay until my sister Victoria started jogging. She called me and said, ‘What do you wear for a bra?’ I said, ‘I don’t really have a good solution. I’ve tried wearing a bra that was a cup size too small, but that doesn’t really help.’”

Then, Victoria made a joke: “Why isn’t there a jockstrap for women?” she asked. Same concept, different part of the anatomy. The sisters thought that was hysterical and howled with laughter.

Then the lightbulb went on. Afterward, Lisa said to herself, “Wait a minute. That’s a really good idea.”

She broke down how a bra specifically made for running, for motion, would be different. There would be no hardware to dig into her skin. The straps wouldn’t fall off her shoulders. The fabric would be soft, yet strong, and breathable. The support would be comfortable, but motion would still be curtailed. It would be easy to get in and out of. It was a wishlist and a prayer.

Then, serendipity entered the room. Lisa didn’t have sewing skills, but her best friend in the world, Polly Palmer Smith, did. The two had met in the eighth grade, when they attended Monclair’s Kimberley School for girls, and they remained friends even after Lisa got kicked out of school and her family moved to New York City. The two stayed in touch as Polly graduated from Moore College of Art & Design in Philadelphia and earned her MFA in stage and film design at NYU.

Polly happened to be living in Lisa’s house that summer of 1977 because she was working as a costume designer for the annual Champlain Shakespeare Festival in Burlington. When Lisa broached the idea for a bra made just for exercising, Polly’s first reaction was, “Leave me alone,” she laughed while speaking by phone from New York. “I was busy, and it wasn’t Lisa’s first wacky idea. It took me a while to realize that she was quite serious. There was no getting away from it because I was renting a room from her.”

Polly brought in a third person to aid their quest: Hinda Schreiber, her assistant that summer at the theater. Hinda was born in Montreal and learned to ski in the Laurentian mountains of Quebec. She and her family regularly crossed the border to ski at Vermont’s Stowe. She had graduated from Parsons School of Design and met Polly while earning her MFA at NYU.

Hinda was a recreational runner and, like Lisa, bemoaned the existing bras. “We were in the first group of college-educated women with the option to be on the track team and get all the benefits of sports,” Hinda told me by phone from Florida. “Running was part of our everyday life. With bouncing boobs it hurt, and the guys are always looking at you and you felt self-conscious. I would run with my hands holding my boobs. Some of us wore two bras. Some of us wrapped our bodies with ace bandages.”

Polly examined every bra on the market to see if there were any redeeming features that she could steal. She sketched ideas and produced samples working off of Lisa’s 34C measurements. “Nothing was working,” Polly said. “It was hard for us to wrap our heads around where we had to go with this thing. We were struggling.”

A second jockstrap reference provided Polly with her lightbulb moment. Lisa’s husband was a bit of a jokester. One day, watching the women despairing over their unsolvable puzzle, Al Lindahl came down the stairs bare-chested, wearing a jockstrap stretched over his torso.

“Ladies … I present your jock-bra,” he announced to the room.

For Polly, seeing the straps pulled over Al’s shoulders, with the pouch stretched over his chest, provided the visual prompt she was missing. It was the “fateful moment when all the pieces fell into place,” she recalled.

Hinda was sent to the UVM bookstore to buy two jockstraps. Polly cut them up and made a crude prototype. The two pouches served as the cups; the waistbands became a solid rib-band that stretched around the torso; the butt straps were converted into shoulder straps that crossed at the back.

The design was itself a radical statement of sorts: a co-opting of a venerable symbol of male jock-dom to craft an object of women’s liberation.

Polly called it “just a construction job,” but its beauty lay in its minimalism. “The elastic going under the breast, with a simple cup that you could make really tight, and then this elastic going over the shoulder and holding everything in place,” she said. “It hadn’t occurred to us before that you could just climb into it, with no hooks on the back or the front. It was like, wow.”

Lisa slipped it on for a test run while Hinda jogged backward in front of her to assess movement. All agreed that it worked; all agreed that it needed tweaking, especially of the fabric and elastic material. Then came the real challenge: How do you manufacture and market a product no one has ever seen or used before?

After the summer, Polly returned to New York to start working for the Jim Henson Company. She found a wholesaler selling three-yard samples of cotton Lycra, a recent advancement in activewear, for the bra cups. (Unlike rubber, Lycra can recover and retain its original shape, and absorbs sweat well.) She also purchased elastic strips with a soft underside—a two-inch piece for under the bust and a one-inch sample for the shoulder straps—and sent each iteration to Lisa in Burlington.

That fall, as she and Al agreed to separate, Lisa consulted an attorney to incorporate the company as SLS (the initials of their last names). She issued 300 shares and divided them equally among Polly, Hinda, and herself, with each woman contributing $100 to the cause.

“Sitting on my living-room floor, we had this discussion about this being by women, for women,” she said. “It was this high-falutin, very 1970s idea of no power-tripping. ‘This is about collaboration, not competition.’”

As she started exploring the patent process for what they were calling the JockBra, Lisa’s expectations for the business were modest. “I was thinking, ‘Oh, this could be a nice little mail-order business on the side to help put myself through graduate school.’”

Lisa sent the prototype to Hinda, who had landed a teaching gig at the University of South Carolina. Hinda consulted with the local sporting-goods store in Columbia, and learned that “Jock” was considered inappropriate for a piece of women’s athletic equipment. They quickly changed the name to the Jogbra.

Hinda borrowed $5,000 from her father to fund a test-run to show to potential buyers, but she struggled to find a textile mill that would manufacture such a limited sample. Finally, she stumbled upon Carolyn Morris, who’d recently been fired from a local factory and was sewing clothes inside her trailer by the airport.

Morris turned the prototype into small, medium, and large sizes, a process known in the industry as “pattern grading.” She and her crew churned out 40 dozen white bras that were delivered to Lisa’s apartment in Burlington. The Jogbra was a reality.

A year had passed. Lisa and Al were divorcing, and she was studying for her master’s degree in educational administration. Polly was working on The Muppet Show. Hinda had decided academia wasn’t for her and was preparing to return to Vermont and devote her considerable energies to the Jogbra.

En route to Vermont, Hinda came through New York City. She arranged a meeting with Polly and said that she wanted to buy out her shares. “She said, ‘My father’s giving me some money, and I’m going to do this Jogbra idea, but I’m not going to do it for just a third of the company,’” Polly recalled. “I didn’t really think it through. I just said, well, I guess that makes sense.”

Polly decided to sell 80 of her 100 shares to Hinda. The suddenness of the transaction left a bitter aftertaste. “It was underhanded,” Polly said. “We should’ve all sat down together and said, ‘We’re going to do this and this is how it’s going to happen.’ It ended up causing huge, huge problems.”

When Hinda arrived in Burlington and told Lisa what had happened, Lisa was flabbergasted. Hinda offered to buy Lisa’s shares too, but Lisa refused. She consulted with her lawyer who’d drawn up the corporation bylaws and discovered that a standard clause in partnership agreements, which would prevent one shareholder from buying the shares of another without the consent of the other partners, had been omitted.

“[The lawyer] didn’t take the situation or me seriously enough to think that was necessary,” Lisa said. “So, I was screwed.”

Hinda hadn’t done anything illegal, but by owning 180 of 300 shares she now controlled the company. “Hinda said that she was now the majority shareholder and that I had to do what she said or she’d fire me,” Lisa recalled. “I’m sitting there going, ‘What the fuck?’

“She was a totally different personality than the woman I’d said good-bye to the previous summer,” Lisa said. “Hinda is a fiery person. The summer before it had been warm, it had been about enthusiasm and excitement. A year later it had contorted into this power play, and it shocked the hell out of me. I kept waiting for the old Hinda to return.”

Hinda describes the situation differently. “I wanted those shares back from Polly [to put into] the company,” she said. “I didn’t really think about it too much, but I know it became a big brouhaha. I didn’t have any pre-conceived anything.”

Soon afterward came what Lisa described as “another betrayal.” She had initiated paperwork for a patent for the Jogbra and had recruited Polly to draw the official sketches that accompanied the application. Lisa listed three names for the patent in the following order: Eugenie Zobian Lindahl, Polly Palmer Smith, and Hinda S. Schreiber.

At a certain point, Hinda took over the patent application and provided material to a patent lawyer in Washington, D.C. When U.S. patent #4,174,717 for “an athletic brassiere” was approved on November 20, 1979, the order of the names on the invention now read, “Schreiber, Hinda S., Lindahl, Eugenie Z., Smith, Polly P.” Subsequent pages read, “Schreiber, Hinda S., et al.”

Lisa admitted that her ego was “bruised” by Hinda’s maneuver to have her name appear first and most prominent on the patent. “I learned, years later, that strictly speaking Hinda was not eligible to be on the patent,” she said. “It was my idea and it was Polly who turned it into a manifest thing, and that is what constitutes invention. Taking it to market does not constitute invention, and yet that was what Hinda’s role was and what her strength was.”

“Oh my God, give me a fucking break,” Hinda said when told of Lisa’s reaction to the patent. “What is the issue? That I put my name first and Lisa thought I should’ve put her name first, right? I wish I was that thoughtful. I am an Aries. An Aries is a person that goes in front, the person that leads the charge, gets things done, sometimes without all the thought in the world about what I was exactly doing. I don’t carry any memory of pre-meditation on my part, and I never have. I will let that go. This was 50 years ago. People can hold onto their issues as long as they want to.”

For three-quarters of the 20th century, the white, male power-brokers who ruled amateur and professional sports sidelined girls and women. Progress arrived some 50 years ago, on June 23, 1972, when President Richard Nixon signed into law the Education Amendments of 1972 (renamed the Patsy T. Mink Equal Opportunity in Education Act, to honor the Hawaii Congresswoman’s efforts in its passage).

The key part of the bill was Title IX: “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any educational program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.”

Vast inequities remain even today, but by requiring schools and universities to provide equal access and resources for women, including athletic scholarships, equipment, and facilities, Title IX dramatically increased the participation of women in sports at every level, from grade school to college, from the pros to the Olympics. Consider one data point: In 1972, some 30,000 women participated in college sports, compared to 170,000 men. In 2020, there were 281,699 male NCAA athletes and 222,920 female athletes.

It was against this backdrop that Jogbra, Inc. (or, JBI) soared. In other words, their timing was perfect.

The initial run of 480 bras sold out. They borrowed another $25,000 from Hinda’s father, which enabled them to apply for and receive a $50,000 loan from the Small Business Administration. (The company would eventually pay back Hinda’s father’s loan with interest.) They hired sales reps, placed ads in the running mags, and rented office and warehouse space. They attended trade shows wearing business suits with shoulder pads and 5ks wearing running shorts and tank tops, and packaged the Jogbra in a clear plastic bag, accompanied by a cardboard insert, for in-store displays. They learned to laugh at the punchlines of every joke thrown their way.

The Jogbra’s motto: “No man-made sporting bra can touch it.”

Lisa handled sales and marketing; Hinda oversaw production and inventory, with the bras now being manufactured at a factory in Puerto Rico. Within one year, JBI reached $500,000 in revenue, with the bras selling at $16 per unit retail, or about $70 in today’s dollars. Sales grew to $750,000 in 1981, and then $1 million in 1982. In the days before personal computers were commonplace, they figured out on the fly how to administer receiving and quality control, packing and shipping, fulfillment and invoicing, payroll and taxes, and customer service duties.

Success didn’t mend their strained relationship. Hinda was a doer, hyperkinetic and impulsive. Lisa, deliberate and cautious, needed time to contemplate even the smallest change. Their oil-and-water personalities never jelled.

“Lisa and I were fighting all the time,” Hinda remembered. “We didn’t know each other. We were both egomaniacs. We came from fear and insecurity. We didn’t know what the hell we were doing. It was stressful and it was a different world. Our struggle was between leadership and ownership.”

“After four years I was getting sick,” Lisa said, “because Hinda would just yell at me. I finally sent her an ultimatum: Either you buy me out or I buy you out or we equalize the shares. But we cannot go on as we have. In my head I was packing my bags.”

Polly, meanwhile, felt guilty for her role in the contretemps. “I think Hinda really wanted [the company] all to herself and resented that she couldn’t get rid of Lisa,” she said. “She just made Lisa’s life miserable. And, here I was, Lisa’s best friend, who put her in this horrible position.”

According to Hinda, her father helped resolve the stock disparity by advising her to equalize the shares or buy out Lisa and find another partner. Hinda decided to stay with “the headache” she knew and sold a portion of her shares to Lisa.

That put Lisa in the awkward position of approaching Polly to purchase her 20 remaining shares. What made the moment tolerable was Polly’s own sanguinity. “I gave up the shares willingly because I was so guilt-ridden,” she said. “Lisa’s friendship was more important to me, and my career was going fine. I was traipsing around London working on The Muppet Show and having the time of my life. I had more fun than they did. I didn’t quite make the big bucks they did, but I was doing fine.”

The lesson that Polly learned from her experience? “Never go into business with friends if you’re not prepared to stab them in the back.”

Lisa and Hinda were forced to tolerate each other. They formed an advisory board of directors to serve as a buffer between them and to offer unbiased counsel on business decisions. They sampled a panoply of personal-growth workshops that were flourishing in the New Age mecca of Burlington: TM and Zen; est and fire-walking; The Money & You and The Human Factor; Tony Robbins and Buckminster Fuller. They wrote a set of operating principles for company behavior, including “Demonstrate gentleness, dignity, and respect,” and “Listen and be receptive.”

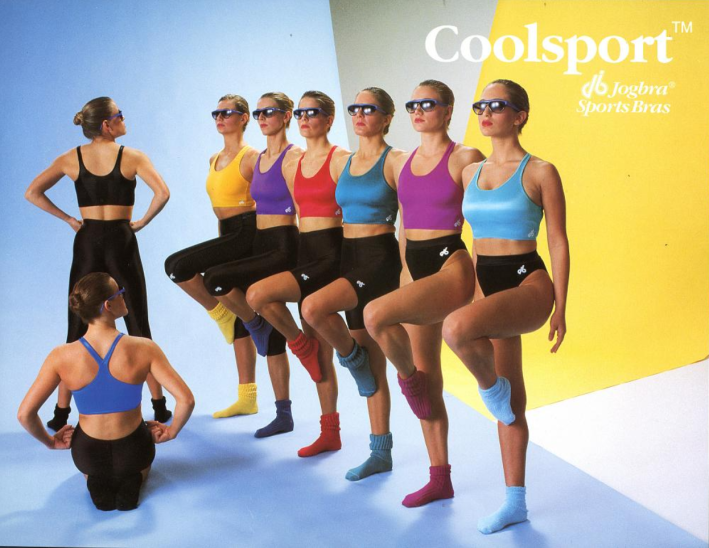

As the pool of female athletes expanded exponentially around the globe, JBI grew at an average of 25 percent per year and posted annual profits. They employed nearly 200 workers and expanded their product line, developing the SportShape bra for large-breasted women and a combination bra-top that covered the midriff. The packaging graduated from plastic to glossy cardboard. They even experimented with men’s support briefs (Max for Men).

“All the money we were making we plowed back into the company,” Lisa said. “But now we realized that we weren’t going to be able to finance our growth internally. If it were now, maybe we would’ve done an IPO.”

A decade of stress and tension, along with looming competition from traditional bra companies like Olga as well as Nike and other sportswear behemoths that were grabbing market share with their own versions of the sports bra, took its toll. “We were coming to a new stage of the business,” Hinda said. “It was clear that we had to expand into department stores, and that takes a lot of money and infrastructure. We’d have to go to the VC people [to raise money], and Lisa and I both realized that with our own personal burnout, with our mishigas, we weren’t able to make that next step.” The time was right to exit.

In 1989, Stamford, Connecticut–based Playtex Apparel, maker of the “18-Hour Bra,” approached them with an offer to buy JBI. The women hired a consultant to help them with the process. As they wavered, and as Playtex upped its bid, their advisor told them, “Either you must decide to sell and for how much, or you have to tell Playtex to go away,” according to Lisa.

Somewhat miraculously, the two women independently came up with the same dollar amount that they would accept from Playtex. The deal was completed in August 1990 for a still-undisclosed amount, split equally between Lisa and Hinda, with Polly receiving nothing for her efforts.

“I would’ve ended up with a pretty big paycheck if I’d kept my shares,” Polly said. “I guess if I was poor and suffering, I would be upset. [Lisa and Hinda] had to work for every penny they got.”

“Back then it seemed like a huge amount of money,” Hinda said. “Now it’s nothing. They got so much value for what they bought.”

They signed handsome contracts to stay on at Playtex as co-presidents of the Jogbra line. Lisa left after two years, the second spent as a part-time consultant. “That’s when it got really ugly,” she said. “Hinda was up to her old tricks, claiming to be the inventor and talking about how she took two jockstraps and sewed them together, without mentioning my name or Polly’s name.” She hired a lawyer to send a cease-and-desist letter to Hinda. It’d be their last communication for a while.

Lisa Lindahl remarried and joined the board of directors of The Epilepsy Foundation of America. (She and her second husband later divorced.) She also designed and patented the “Bellisse Compression Comfort Bra” for breast cancer survivors. She earned her Masters of Arts in Culture and Spirituality from Holy Names University in Oakland, California; graduated from the Foundation for Shamanic Studies’ Program of Advanced Initiations; and published two books, titled Beauty As Action: The Way of True Beauty and How Its Practice Can Change Our World, and Unleash the Girls: The Untold Story of the Sports Bra and How It Changed the World (And Me).

“Partly why I wrote the book was because I didn’t want the ‘Yea, women!’ thing to be the only perspective,” she said. “Women are just human beings. The use and abuse of power does not depend on genitalia. I think, as humans, we suffer from species-ism. We think we have more rights than the plants, than the trees, than the animals.”

After The Muppet Show, Polly Palmer Smith worked on other prominent Jim Henson projects, including The Muppets Take Manhattan and The Dark Crystal, and Sesame Street. She’s won eight Daytime Emmy Awards for costume design/styling. She claims that she’s retired, but admits that she still takes on work from time to time.

Polly said that she takes more pride in her costume design résumé than from her Jogbra contributions. These days, when she works out at the gym, “seeing all the women strut around in their sports bras makes me snicker,” she said. “Like, if they only knew…”

When the cabin next door to Polly’s family’s summer place on Lake Champlain came up for sale, Lisa bought it. She and Lisa remain best friends.

Hinda Schreiber stayed on through the sale of Playtex Apparel to Sara Lee in 1991 (a deal valued at $575 million) before exiting in 1997. She married her husband, Joel Miller, and they have two children. She joined the board of Green Mountain Coffee Roasters, which started as a single café before going public and acquiring Keurig, then spent 10 years in the Vermont State Senate before retiring in 2012.

Her unsuccessful campaign for mayor of Burlington in 2006 was hamstrung by critical remarks from Lisa, as well as Lisa’s refusal to endorse Hinda. An article in Seven Days, a Vermont newspaper, noted that the two women have an “abysmal personal relationship” and “haven’t spoken for more than 15 years.” Hinda also wrote a memoir: Pearls of a Sultana: What I’ve Learned About Business, Politics, and the Human Spirit.

“It’s all ego, it’s all la-de-da, aren’t we great,” Hinda said of her book. “I needed to get it out, my point of view, because my role in the Jogbra has always been underestimated, because there’s so much more than just the idea. I was an integral part of the doing-ness, of the manifestation, from an idea and a sample to a business.”

Hinda said that she’s writing a new book, “from the inside out,” that draws on her 40 years of practicing yoga. Asked whether she’s read Lisa’s book, Hinda replied that she hadn’t. “I have it right here. The truth is, I don’t want to face all that stuff.”

After a series of corporate mergers and acquisitions, Champion, which is owned by Hanes, took over the Jogbra brand. The Jogbra no longer exists in the marketplace, but the sports bra, in myriad styles, designs, shapes, sizes, colors, materials, and brands, is estimated to be a multi-billion-dollar global industry.

“Once the T-shirt came off over the bra,” Polly said, “it was like a whole new revelation of sportswear.”

The object of their affection that brought the three women together in the first place, only to tear their relationship apart as a start-up business, has been instrumental in their recent moves toward reconciliation. What prompted their wary rapprochement was the ongoing demands from media outlets to tell their story, however edited and scrubbed for public consumption.

In 2016, Eva Longoria directed a 10-minute documentary for ESPN titled Revolution: A History of the Sports Bra. The upbeat film introduces “the three friends,” describes the Jogbra’s synergy with Title IX, and traces its cultural significance—cue the indelible photograph of Brandi Chastain, kneeling in a black sports bra as she celebrates her World Cup-winning PK against China in 1999—without mentioning the conflicts or the trauma.

“They were not interested in the inner workings about how this company worked,” Hinda said.

The production marked “the beginning of a new chapter” in their relationship, according to Lindahl. As interview requests multiplied, the women were showered with accolades. The Smithsonian National Museum of American History has collected and digitized the Jogbra archives. On May 5, the three will be inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

These appearances have forced them together. Sitting in coffee shops and hotel bars as they prepare to face the camera and tell their story yet again, laughing over triumphs and bemoaning mistakes, the three septuagenarians have measured each other, begun to acknowledge the hurt they’ve caused, and above all else relished their roles as emancipators.

“We’ve had many come-to-Jesus meetings with Hinda,” Polly said. “When we went down to the Smithsonian to give a talk, right before the lockdown, I think we finally got through to her. At dinner that night, Hinda said, ‘I’m so glad that we figured this all out,’ and Lisa and I are looking at each going, ‘How many years did it take for her to get this?’”

Lisa and Hinda have found that they agree on one aspect of the story. “There was no one time when I [knew] this was going to be a great iconic product,” Hinda said. “It was a daily grind. We weren’t visionaries for the future. We were on the ground. It was a time of our life where we could take a chance.”

“At the time, I had no idea about the cultural impact of the sports bra,” Lisa said. “We were in the throes of running a business. It was like trying to keep up with a cyclone.”