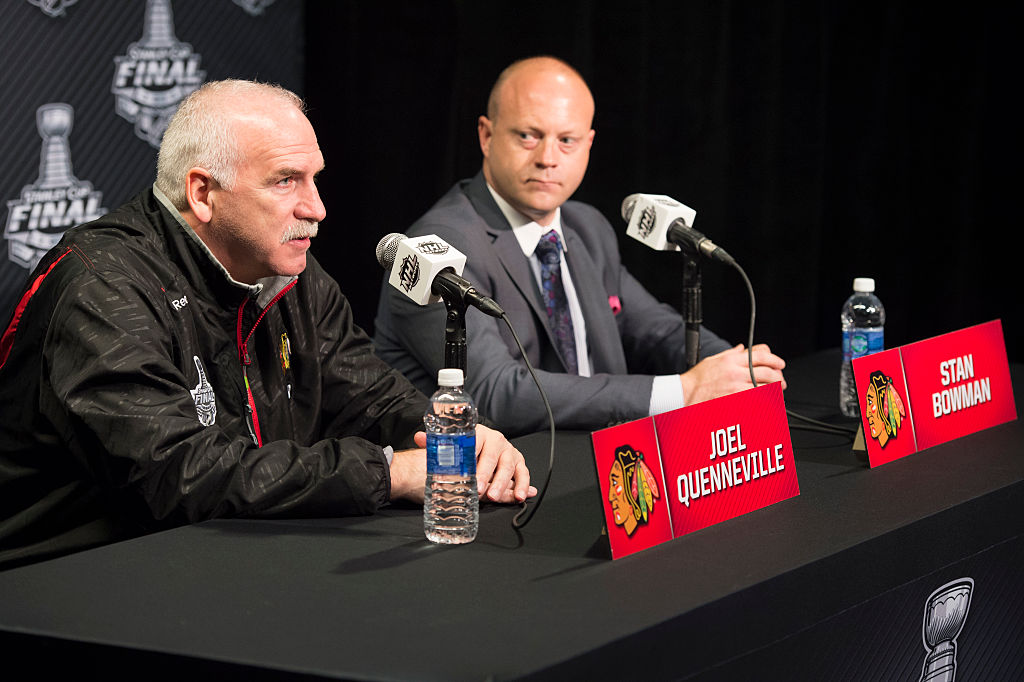

In a move that the NHL very likely intended to bury under a deluge of free-agent news, the league announced on Monday that it as reinstated former Chicago Blackhawks coach Joel Quenneville, former GM Stan Bowman, and former assistant GM Al MacIsaac, who were all banned from the NHL in October 2021 after an investigation uncovered how the team failed to act on a sexual assault allegation during its championship-winning season in 2010.

At the time of their ban, Kyle Beach, who was called up to Chicago's practice squad during their Cup run, had just identified himself as the John Doe in a recent lawsuit against the team. The lawsuit, which was settled confidentially, alleged that former video coach Brad Aldrich masturbated in front of Beach without his consent, sent inappropriate text messages, and threatened him “physically, financially and emotionally” if he “did not engage in sexual activity.”

According to a law firm's investigation in the aftermath of the suit, leaders in the Blackhawks organization learned of the allegation against Aldrich during the playoffs but elected to let it slide until after the season was over. After Chicago won the Cup, and Aldrich participated in the celebrations, they gave him the option to resign. Aldrich went on to work in the NCAA, where he left Miami University (Ohio) in 2012 following an accusation that he sexually assaulted an intern at a summer hockey camp. No charges were filed then, but in 2013 Aldrich was convicted of sexual contact with a minor while working as a coach at a high school in Michigan. He served nine months in prison and registered as a sex offender. It's not hard to connect the Blackhawks' silence with Aldrich's continued ability to get jobs that placed him near young athletes.

The long-delayed consequences for the team's leadership at least felt serious at the time: Bowman stepped down and MacIsaac was fired from the Chicago organization ahead of their ban, and Quenneville resigned as head coach of the Panthers before his ban officially came through. (Team owner Rocky Wirtz, an asshole nevertheless exonerated from direct culpability by the investigation, died in 2023.)

Without Quenneville, the Panthers achieved unprecedented franchise success, first with a Presidents' Trophy and then with back-to-back Finals trips culminating in a Cup last month. In Chicago, Wirtz's son Danny and new GM Kyle Davidson were gifted a chance to start a new era when they won the draft lottery in 2023 for wonderteen Connor Bedard. The legacy of Aldrich, however, still feels like an open wound—the most prominent of many recent stories about hockey's widespread sexual misconduct problem—as the sport continues to handle these scandals in ways that prize secrecy above all else. Hockey's rot won't be fixed simply by scuttling off a few individuals after they're accused; its misogyny, homophobia, and sexual violence need to be squashed by leaders at the youth level and visibly condemned by those at the top of the pros. What continues to chill me most about the charges against members of the 2018 Canadian World Juniors team is that the alleged gang-rapists came from teams stationed all across the country. The one thing they had in common was hockey culture.

The league justified lifting the ban on Bowman, MacIsaac, and Quenneville after less than three years with the usual lines about how they've learned and shown remorse and improved themselves. I'm sure they'll find jobs before too long, because the NHL loves giving second chances—just look at Corey Perry scoring for the Oilers in Game 5 of the Stanley Cup Final, in the same season he was waived by Chicago for still-mysterious "conduct that is unacceptable, and in violation of both the terms of his Standard Player's Contract and the Blackhawks' internal policies intended to promote professional and safe work environments." These newly employable suits are too well-connected to be allowed to fade away, and too many teams believe they're just one personnel move away from unlocking a contender. That'll be its own story when a franchise bites. But whatever does or doesn't happen to them, these three men aren't hockey's problem—they're a symptom.