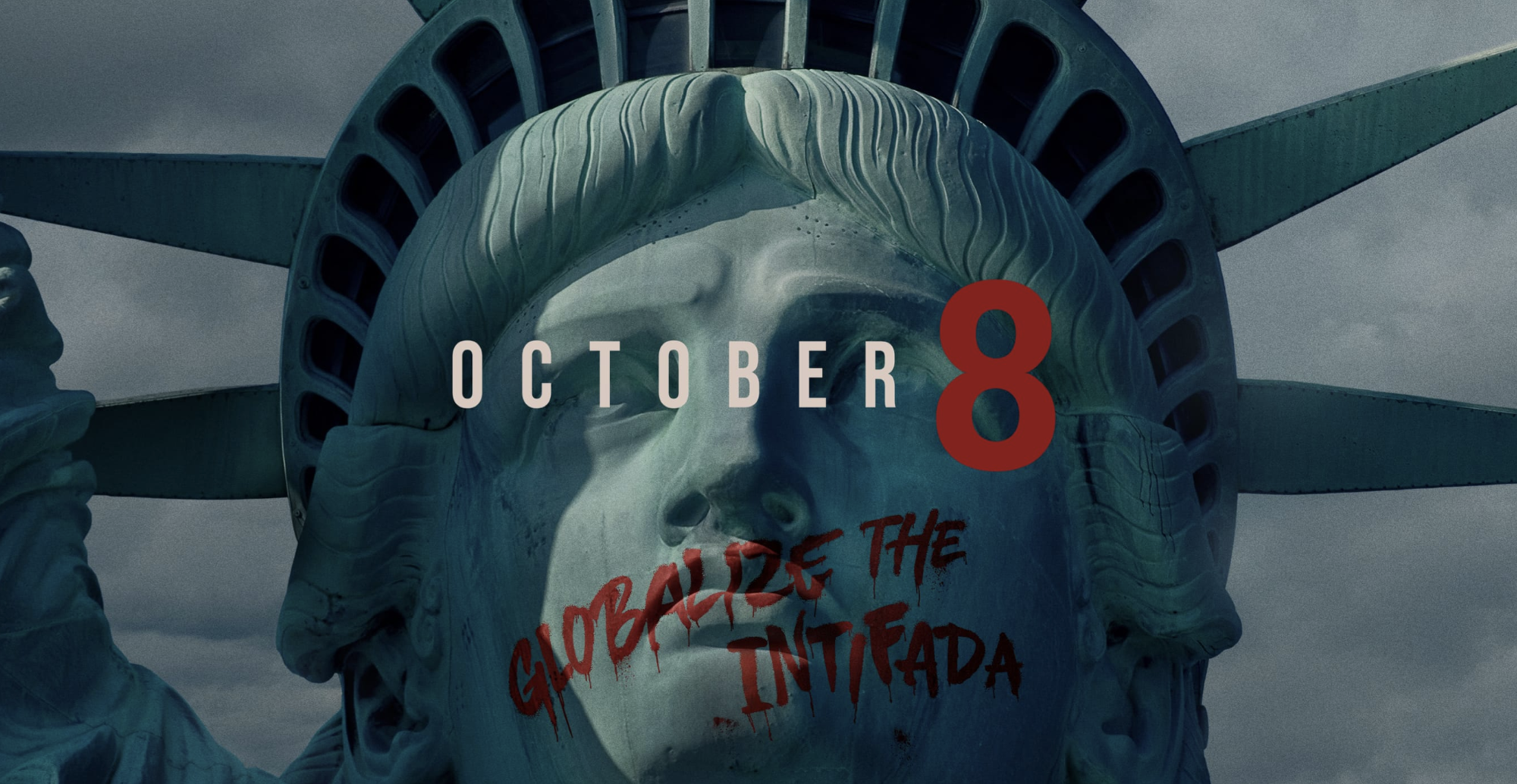

What you need to understand about the Zionist propaganda project October 8 (originally titled October H8te) is that calling it a film at all is generous. The documentary, directed by Wendy Sachs, is made in the Streaming Network House Style—drone shots, center-frame interview subjects, a manipulative soundtrack so on the nose that it becomes downright obsequious—and so it has a certain affinity with the dime-a-dozen true-crime cash grabs churned out by Netflix and Hulu. But those productions, shoddy as they may be, generally understand concepts like "pacing" and "narrative structure."

Here, not so much. Certain political threads are picked up only to be quickly abandoned or pursued half-heartedly. As much of the movie is taken up by Zionists complaining that they're being given the cold shoulder by the progressive-liberal coalition in which they previously felt at home—Jews marched with blacks in the civil rights movement, one talking head whines, so why aren't blacks marching for Israel?—as it is with Zionists (sometimes the same ones) speedrunning a Republican media checklist: "DEI is antisemitism," "Communist Chinese TikTok is corrupting the youth," "Hamas is bent on the destruction of western civilization," etc. A brief passage in the middle of the film promotes the idea that campus groups like Students for Justice in Palestine are either providing material support for terrorism or are "terrorists" themselves. They are never clear on which argument they're pushing, but as soon as the sequence is over, the filmmakers move on, never to return.

There is also a conspicuous absence at the core of the film: Gaza. The film opens with some footage taken by Hamas and associated militants on Oct. 7, a short interview with an Israeli woman in front of her destroyed home in one of the kibbutzim attacked that day, and a slightly drawn-out shot of an Israel-Pride flag, as in a mashup of the Israeli flag and the Pride flag, fluttering among the rubble. (Israel never misses a chance to do some pink-washing, even as its supporters scream lurid rape and murder fantasies at every LGBTQ supporter of Palestine within earshot.) Aside from these opening scenes and a single short scene near the very end, it is as if Gaza does not exist at all. Even Israel itself barely exists in this film: No Israeli officials are ever named, and the state and its history are hardly mentioned, if at all.

Both are mere background for the real subject of the film, which is the wounded, paranoid feelings of American Zionists. And for this, we must leave Israel and head to the heart of the action: the phone.

October 8 is not so much a film as it is a way to experience being trapped in a room with someone as they show you posts on their phone. I do not mean this figuratively: A significant portion of October 8’s 100-minute runtime is composed of people watching videos on their phones, images of tweets or Instagram posts, shots of videos playing on Twitter or TikTok, or people you vaguely recognize from Twitter talking about things they've seen on their phones. At one point, I went on Twitter out of boredom, only to realize that I was essentially now viewing the film in double.

We watch as various American Zionist influencers watch Al-Aqsa Flood unfolding on the morning of Oct. 7, and then we watch their Instagram live recordings of them watching. We watch Shai Davidai watch a video of himself crying and screaming (his only two modes, aside from whining) at a sparsely attended rally at Columbia in real time, after which he turns to the camera, exhales, and says, "That’s the rawest I've ever been." Interviews are interspersed with archived protest footage from Instagram live streams. Most of the interview subjects, like congenital liar Eyal Yakoby or Hen Mazzig, the softboi of the online hasbara circle, earned their spots in the film exclusively through posting a lot.

The phone screen and the social media feed together have a symptomatic primacy here: Together they are the perfect medium through which to both channel and deepen the violent paranoia at the core of the Zionist psyche. Early in the film, an otherwise forgettable talking head says that part of what made Oct. 7 so horrific is that the "terrorist" attack occurred also "on our most intimate platforms"—by which she meant, of course, the phone. Paranoia is an interpretation mania, a filter: Everything external and differentiated is brought under the single heading of threat. The screen and the feed work to generalize that delusion. The Zionists in the film felt personally victimized by Oct. 7, despite living in the United States, because the attack was filmed, was available for viewing—the phrase bears repeating—on "our most intimate platforms." The screen collapses time—the feed as an undifferentiated continuity of events—but more importantly here, collapses distance as well. Guy Debord's first thesis in The Society of the Spectacle is as instructive as ever: "Everything that was directly lived has receded into a representation." The problem deepens to the extent that the screen becomes a constant companion, a means of documenting and consuming, often simultaneously. To live under such conditions means that we are increasingly experiencing things as first or simultaneously mediated by their own appearances, even when the experience is "lived." The screen becomes the subjective site of perception, bringing everything within the same proximity, regardless of its actual objective distance. An event which occurred there and can be felt to happen over and over again here and now. We see the thing and its image together, and representation takes on an equivalence to presentation.

This is also the formal equivalent of paranoia. For the paranoiac, things take on a dual reality: the stimulus itself and its place within the web of delusion. Distant violence is perceived as a threat to oneself. This paranoia holds together the film's otherwise divergent and scatterbrained threads. At one point, footage of various high-profile attacks against civilians in the U.S. and Europe (like the Boston marathon bombing and the Bataclan shooting) accompanies a voiceover stating, "If Israel does not defeat Hamas in Gaza, Hamas will prove that it is possible to bring a democracy to its knees." Earlier, a shot of a bombed-out kibbutz cuts to archival footage of Eisenhower touring a liberated concentration camp, then back to the kibbutz. Generational trauma is mentioned. A woman cries: "Jewish people felt it as a genocide attack intended for them." Multiple figures repeat the now-familiar phrase, "This was the deadliest day for Jews since the Holocaust." The specter of the Shoah haunts every action, no matter how innocuous or unrelated. Jewish students claim to feel unsafe because student protestors chant "All Zionists are racist." Images of genuinely antisemitic messages from a Telegram chat with a few hundred members called "Professional Cyberbullying Russians" or from random Telegram users like "uksteve" are interspersed with TikTok videos of protestors chanting "From the river to the sea." A video posted on Twitter as an example of violence against Jewish students instead unequivocally shows a person attacking a pro-Palestine protestor and trying to rip the flag from their hands. For the paranoiac everything on the above list is the same, all of it a threat: It all fits within the web, all part of the timeline scroll.

Repetitions emerge in the form of familiar speech patterns, phrases, fears, and projections. There is a memetic quality to the Zionists on screen. I mean this in a dual sense: On the one hand, as the philosopher Theodor Adorno writes, "the fantasy of persecution is contagious: Wherever it occurs spectators are driven irresistibly to imitate it." The absence of any actual threat deepens the paranoia further, as ever more byzantine webs are required to sustain the delusion. The Zionists find comfort in their shared sense of persecution, in their flight from the idea that things may not be so bad as they seem. Against reality's lack of resistance, friction must be invented.

On the other hand, I mean memetic in the internet sense—literally, these people speak in memes. If they seem to ape one another, it is because they draw from the same impoverished source material: i.e., their phones. A small sampling of stock phrases which made the leap from the Zionists' phones to their mouths and vice versa: "No one asks if China has a right to exist," "the deadliest day for Jews since the Holocaust," "I wasn't seeing an ideological disagreement between two sides, I was seeing hatred," protestors see the world only as a split between "the oppressors and the oppressed," and on and on. At one point Deborah Lipstadt, who served as Joe Biden's Special Envoy for Monitoring and Combating Antisemitism and who also wrote a book about Eichmann, outrageously claims to have invented "horseshoe theory."

For a film that is ostensibly concerned with the "war over narrative and sometimes truth," as IDF Major Liad Diamond puts it early on, almost no effort is made in the way of rational argumentation or "corrective" education. It is tempting to attribute this to the indefensibility of the Zionist position and the clear absurdity of their legal and historical claims. This one of the main causes, to be sure, but the incoherence of hasbara is also its strength. Adorno again: "The very 'phoniness' [of belief in fascist propaganda] may have been relished cynically and sadistically as an index for the fact that power alone decided one's fate in the Third Reich, that is, power unhampered by rational objectivity." Indeed, it has become exactly such an index: Zionists slander the Palestine solidarity movement, and Mahmoud Khalil and Rümeysa Öztürk and numerous others are kidnapped by ICE and whisked away to detention facilities in Louisiana. The very things the Zionists claim to fear—being targeted because of their identity or political positions, for their speech, for their activism—are actually happening to Palestinians and others within the Palestine solidarity movement. In late March 2025, The National Jewish Advocacy Center (NJAC), along with several law firms, filed a lawsuit against various Palestinian advocacy organizations—including Columbia Students for Justice in Palestine and Within Our Lifetime. The lawsuit alleges, among other things, that the defendants "so pervasively and systemically assisted Hamas as to render them liable for every Hamas terror attack and action." The claim is plainly absurd, but it requires the defendants to mount a defense, and also can be seen as a dry run for potential criminal prosecutions, testing the water for the idea that pro-Palestine speech is in fact material support for terrorism. The claim's absurdity, however, also serves a function. Zionists must constantly up the ante in order to sustain the delusion, and the more outrageous the claim, the louder the call for some kind of retaliatory action. The U.S. and Israeli governments heed the call and give these delusions a violent reality, further entrenching the worldview. "The sadism latent in everyone unerringly divines the weakness latent in everyone," Adorno writes. "It is the rhythm of total destruction."

As I've written elsewhere, "The repeated and almost exclusive use of slogans and cliches serves to fashion out of the Zionist polity and its supporters a stereopathic type: Rational argumentation requires the engagement of an individual subjectivity, reciting slogans only memorization …Through repetition, people congeal into a mass and adopt an obedient group psychology." The obsession with the phone throughout the film signals the medium by which the stereopathy is achieved. The mass dissemination of images and phrases on the timeline draws paranoid subjects together in a shared web, the smoothness of the algorithm offering as little resistance as reality itself. Paranoia, like Twitter, can be a lexical madness.

I do not mean that Zionists exist in an echo chamber, where only the same ideas can be heard and counterarguments are excluded. I mean there are no ideas at all, only facsimiles of ideas in the form of slogans, videos, and memes. The short format imposed by social media platforms all but ensures that language will take the form of a slogan and the video will take the form of a clip: repeatable, digestible, memorizable. Everyone online already writes like they're their own PR agent anyway. The mannered house style gleaned from social media's predecessor, the press conference, primes the listener to be receptive to sloganeering and cliches as much as it primes the speaker to deliver them.

People remember Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem for the oft-abused phrase "the banality of evil," but it is her linguistic insights that are of use with respect to Zionists. We are, after all, largely not talking about bland careerists here—Ritchie Torres excluded—but rather paranoiacs driven toward violence by the phantoms in their heads and the psychical and material benefits of colonial domination. The aspect of Adolf Eichmann that Arendt found most troubling, and also most comical, was his inability to utter "a single sentence that was not a cliché." Whenever questioned, he "repeated word for word the same stock phrases." What Eichmann's reliance on cliché evinced was a complete inability to think. To speak only in stock phrases is to abdicate one's capacity for thought to an external force—to quite literally draw one's words, and the ideas they communicate (or lack thereof), from a pre-given well. The mind ossifies, and the phrases become rote and devoid of rational content, and thus all the more capable of animating libidinal energy free from moderation.

Toward the end of the film, Sheryl Sandberg—former Meta COO, coauthor of Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead, and the primary mover behind another Zionist propaganda film, Screams Before Silence—tells a story. She is talking to her friend about Oct. 7 and the protests she's seen on the news (her phone) and, overcome with fear, asks: "Will you hide me? Like if it comes to that, will you hide me and my family?" Another cliché, another stock phrase. Sandberg continues, "Do I really think that's gonna happen in America? No. And it was interesting because [my friend] didn't really know what I was talking about."

Arendt writes that Eichmann's inability to think was, "namely, an inability to think from the standpoint of somebody else." The Zionists' memetic manner of speech demonstrates a similar incapacity. Paranoia clouds out the Other entirely, replacing their opacity with the false transparency of pure projection. They take the content of others' minds to be the same as their own. Sandberg's friend had no idea what she was talking about because the question was, when measured against reality, insane. Arendt continues, referring still to the use of clichés and stock phrases, "no communication was possible with [Eichmann], not because he lied but because he was surrounded by the most reliable of all safeguards against the words and the presence of others, and hence against reality as such." Eichmann was ultimately hung for his crimes; he could only safeguard himself from reality for so long. Then as now, reality has a way of pushing back.