Kurt Evans drifted into his New Haven office on the Monday morning of April 19, 1999, hours after working the NFL Draft that weekend. Evans was the Professional Teams Coordinator at athletic apparel manufacturer Starter and was tasked with making sure drafted players wore the right caps at the podium. As he checked his messages, an employee from the company’s finance department walked in, closed the door and sat down.

“I think we’re finished,” he said.

It wasn’t a secret that the company had fallen on hard times since the manufacturer had transitioned from privately owned to publicly held six years earlier, and posted substantial losses in the most recent few quarters. But a restructuring of the top brass months earlier had brought back company founder, David Beckerman, to lead Starter and to work out loan agreements to stay solvent. So Evans wasn’t buying it.

“Oh. Come on. Really? So extreme?” he said, incredulous. “That can’t be the case. I was just shipping out more hats to the Vikings.”

Evans admitted he hadn’t paid attention to the warning signs as closely as he probably could have. Originally from nearby Shelton, he was in his 11th year at Starter after talking his way in as the company’s first intern, ultimately climbing the ranks to operate as a liaison between the teams and the manufacturer, making sure players and coaches wore the correct products on the sidelines so that the apparel line’s infamous “S with a star” logo was visible. Who has time to worry about balance sheets when you’re playing phone tag with Bill Parcells?

Some in the office felt like the culture was slowly returning to where it had been in the company’s heyday. With Beckerman’s charisma and vision, a few employees believed the band was back together. Besides, things weren’t that dire. Starter still supplied uniforms to a handful of professional teams and were one of the biggest licensees in MLB with the clothier’s famous satin jacket. They were preparing a slew of new clothing items for release in the coming months.

“I felt really good about our product line that year,” said Bob Felice, who doubled as Vice President of International Sales and Beckerman’s son-in-law. “I really felt like there was a change coming in where we were heading with the product.”

A couple of hours later, a company-wide email requested everyone meet in the second-floor warehouse. There, Beckerman addressed his employees. He had created this company almost 30 years ago with a simple satin jacket sample he kept in the trunk of his car, growing the small manufacturer from an outfitter of local bowling teams and little leagues to Pro Bowlers and the Major Leagues. The brand had become one of the most recognized in not just sports apparel but in clothing, grossing nearly $700 million in annual sales at its peak. Starter was outfitting athletes and celebrities, and then an entire nation of sports fans who were clamoring for the merchandise because it was on athletes and celebrities.

“You couldn’t miss Starter,” said Marcy Silverman, who worked in marketing for the company until it folded and whose father, Billy, designed Starter’s logo. “Anywhere there was an athlete or a team, we were there.”

Yet the company was finding it harder to compete with the shoe companies who were gobbling up the league partnerships—relationships that in many cases had been personally forged by Beckerman. Starter was indeed closing, filing for Chapter 11 that very day.

When Evans walked out of the warehouse he came face to face with the floor-to-ceiling mural on the wall of the University of Florida Gators scoring a touchdown in the National Championship Game a couple of years earlier, dressed head-to-toe in Starter uniforms.

“How could the company that put that in front of millions of people on television be out of business?” he wondered.

Beckerman put a lot of his things on television. What he left is a legacy that lives on in the seemingly endless amount of fan apparel available. Ever rushed to buy championship gear after a win? That’s Beckerman. Ever sought a specific brand name because it was what the team wears? That’s Beckerman too. The dugouts and sidelines being a season-long fashion show that includes alternate uniforms? That’s all Starter and the companies that followed in its footsteps.

“He was really inventing a category that wasn’t part of the ongoing experience, but it became a part of the authentic experience,” said former NBA Commissioner David Stern in November of 2019, weeks before an aneurysm would claim his life. “He really crafted the category and he deserves a lot of credit for that.”

“I always say about David: He’s the guy who made fandom a wearable experience,” said Carl Banks, former NFL linebacker and one of Starter’s first brand ambassadors in the 1980s, who is now President of G-III Sports Apparel.

Two years ago, Starter celebrated its 50th anniversary amid a bit of a renaissance, thanks to a vintage clothing boom and a familiar name recreating some old standards. Here’s the story of shiny satin, puffy parkas, and how an ambitious body bag–maker and his team of 20-somethings turned an upstart outerwear company into one of the most popular brand names in the world.

“What else ya’ got?” David Beckerman demanded in his rumbling New England baritone.

He isn’t exactly sure why he agreed to do this interview and I’m not totally sure why I asked. What started as a search for the Portland Trail Blazers jacket of my youth—the same one Run wore in the Run-DMC “Christmas in Hollis” video—led me down a rabbit hole: What happened to this company, anyway? An email led me to Beckerman’s New Haven office in September of 2019. Sitting in an armchair, he’s relaxed and casual. Dressed in a pair of cream-colored khakis and a button-down dress shirt, he sits in a padded armchair with a leg draped over the armrest like a teenager. The curly white hair and glasses give him the look of Lewis Black without the irritability—until the topic drifts to the professional sports leagues he used to work with.

He’s been approached for interviews and been asked about writing a book and declined both. It’s in the past, he says. His only memento in the office from those days is a picture of a Starter ad with Connecticut native Tom Seaver posing in a red satin Cincinnati Reds jacket. Conversely, his high school basketball coaching career takes up an entire wall and a display case with pictures and trophies.

Beckerman, who turned 80 on Christmas Day, doesn’t answer questions so much as he monologues. Like about the time he was in St. Louis for the 1982 World Series, attempting to sell jackets to a local sporting goods store chain. He was rebuffed by the owner, who had a replica line that did just fine and was about 25 percent cheaper. That night, Cardinals pitcher Joaquin Andujar took a line drive off his ankle. The medical staff, wearing Starter jackets against the cool Milwaukee evening, rushed onto the field and tended to Andujar—with the camera zoomed in on the pitcher’s ankle, capturing the trainer’s hands and the company’s logo on the cuff.

The phone rang in Beckerman’s hotel room the next morning.

“You son of a gun,” the store owner barked. “They don’t even know who you are! They don’t even want my inventory. They want the one with the S and the star.”

Beckerman’s star was on the rise even before Starter. At 28 years old, he was owner of Plastic Fabricators, having acquired the company after his then-father-in-law brought him aboard to run the business. They assembled disposable items such as shower caps, typewriter covers, and body bags. He’s quick to point out that the manufacturer, which counted Smith Corona as its biggest client, wasn’t just a body bag maker—but that was certainly its most notable product. One of his biggest and most memorable orders was for hundreds of shrouds to be shipped to Jonestown, Guyana, where over 900 people were poisoned with potassium cyanide–laced Flavor Aid by cult leader Jim Jones.

Within a couple of years of taking over, Beckerman had tripled sales. Life was pretty good for a guy who grew up shining shoes and delivering newspapers in a working-class section of New Haven. His father was a union shop steward, his mother worked for the city, and the family didn’t own a telephone or television until he was 15 years old. He did have one small problem: He hated the business.

“You couldn’t be creative,” he said. “What am I going to do? I’m gonna make body bags in different colors?”

What made sense to Beckerman was consumer products, the industry he had started his career in with athletic apparel company Duckster before making his way to manufacturer Pro Golf. He had a sample jacket sewn and was introduced by a mutual lawyer to local salvage store owner Rueben “Ruby” Vine, who cosigned a $25,000 loan. Beckerman offered anything he had of value as collateral, including his car and his watch. That was Starter’s humble beginning.

Within a couple of years, the neophyte company was supplying jackets to local teams and pizzerias with sewn-on logos. Most orders came by the dozen or two—a softball organization needing coats for the new season or a bowling league handing them out as awards to a championship team—except for one frequent order from a small Boston retailer. This Massachusetts store was ordering 50 to 75 navy blue jackets with white-and-red ribbed cuffs. Plain. No names, graphics, or logos. First a couple of orders came, but once it became a regular occurrence, Beckerman hopped in his car to go investigate.

Before it became a popular hat manufacturer, Twins Enterprises was a small storefront operated by brothers Arthur and Henry D’Angelo no more than 20 feet from Fenway Park. They were buying Beckerman’s plain jackets, sewing on a Red Sox logo, and selling the coats as team-issued jackets, with the retailers having an agreement with the team to sell the product as a de facto concessionaire.

The light bulb went on.

As crazy as it sounds today, where every uniform combination is available to fans at the tap of a smartphone, not everyone was on board with the idea of authentic apparel.

The first known licensing agreement in professional sports was signed in 1928 when 16-year-old entrepreneur David Warsaw, founder of now-defunct Sports Specialties, struck a deal with the Chicago Cubs to manufacture Wrigley Field–shaped ashtrays. Yet by the late 1970s, there still were few offerings for consumers. Many of the league’s executives believed that only children would be interested, and some teams blanched at the notion of fans wearing team apparel, believing it would diminish the brand.

“Do you think I want every kid in the city walking around in a Yankees cap?” general manager George Weiss incredulously asked in the 1950s when hat day was presented as a promotion.

“You could always buy stuff in the concourses at the arena,” said Gary Adler, who owned and operated The Complete Athlete chain of stores in the New York area. “But it was always a four-dollar piece of crap t-shirt that sold for $15.”

“You could buy flame-retardant t-shirts, cheap hats and pennants,” said John Bello, who joined the NFL’s licensing arm in 1979 and became president of NFL Properties seven years later. “There wasn’t a big merchandising program.” In those days, the counterfeiters were doing a better job of outfitting fans than the leagues. One of Bello’s first assignments was to chase down copyright infringers, including a bootleg store on Pier 39 in San Francisco that dubbed itself The NFL Shop. He found this activity both ludicrous and telling.

“All that means is there’s a demand out there and the infringers are selling better, more quality merchandise than our licensees are making,” he said. “Growing up as a sports fan, I always wanted to wear what was stolen out of a locker room. Anything that was real.”

It wouldn’t be until sport’s old guard was slowly replaced by younger and more entrepreneurial employees like Bello—people who were fans as well as businesspeople—that the mindset evolved. As a young man, Rick White sat in the stands at Dodger Stadium watching pitcher Ron Perranoski make his way onto the field from the bullpen in a shiny blue satin team jacket.

“If I could ever get that jacket, I would be the luckiest guy in the world,” he remembered thinking.

Almost two decades later, White was an employee in MLB’s licensing division and talking to the small Connecticut jacket manufacturer who was not only applying for a license but pitching his childhood fantasy. The two sides reached an agreement to create adult-sized jackets with Starter paying an annual fee of $25,000 plus a five percent royalty. Beckerman inked similar agreements with the NHL and the NBA, who had just hired a daring young buyer from Jordan Marsh department stores named Bill Marshall to head up its licensing division. Marshall created “team stores” for the retailer, which sold the first licensed Larry Bird t-shirt in youth and adult sizes and netted $500,000 seemingly overnight.

Now with the NBA, Marshall discovered 90 percent of the league’s revenue was from non-apparel, possibly because the offerings were terrible. “There was one company that made t-shirts and their idea of a Knicks t-shirt was a brown t-shirt with an orange logo,” he said. “They didn’t even understand colors. It was a real mess.”

By the early 1980s, Beckerman had a small factory at 360 James Street in New Haven, with a team of locals cutting the sewing materials delivered by truck drivers like Tony Amendola.

With a pack of cigarettes rolled in his sleeve and a swear word readily available, Amendola couldn’t be more typecast for his gig. Beckerman, who could converse with anyone from league commissioners to the janitor, befriended the teamster and donated jackets to Amendola’s church softball team. The trucker wanted to introduce Beckerman to one of the nuns at the local parish, but the company owner begged off.

“I know a lot of people in fuckin’ baseball,” Amendola said one afternoon. “I could help you with these jackets.”

Beckerman took the comment with a grain of salt, since truck drivers weren’t known for their address books overflowing with Major League contacts. What he didn’t know was that Amendola’s children attended West Haven’s Lady of Victory school, where Sister Marguerite Torre worked. Through Marguerite, Amendola met her brothers, Joe and Frank, the manager of the New York Mets and the head of the bat division of Rawlings Sporting Goods, respectively. For a decade, Amendola had used his vacation time to drive Rawlings’s truck to Florida and use a lathe to shape blocks of wood into baseball bats.

“I’m probably the richest guy in the world with all of the contacts I’ve made and the people who are nice to me,” Amendola said when he was profiled by the Orlando Sentinel in 1986. “There isn’t anywhere in the U.S. I could go without knowing someone and having them invite me to their home.”

A few months later, as Beckerman manned a booth the size of a couch at a sporting goods convention at the old New York Coliseum, a buzz started across the room and moved toward his setup.

“I cannot believe this truck driver is walking with these guys,” he thought.

On one side of Amendola was Billy Martin and on the other was Joe Torre, who thanked Beckerman for being kind to his friend and his sister. It was then that the puzzle assembled in his head: Torre’s sister was The Sister, the nun Amendola had mentioned. Torre asked if he could do anything to help the upstart manufacturer. Beckerman quickly handed him a jacket. Any chance you could wear these in the dugout?

“That’s all you want?” Torre asked.

Starter now had an intangible most manufacturers didn’t: authenticity. It wasn’t just a jacket; it was the jacket the Mets wore.

Meanwhile, Rick White didn’t have nearly as easy a sell within the stodgy offices of MLB, where Commissioner Bowie Kuhn considered selling the apparel that teams wore to be crass commercialization. When White met with a council of owners to discuss the idea, Yankees owner George Steinbrenner belligerently lit into the young employee. It was a modern twist on George Weiss’s decades-earlier gripe: What happens when someone gets arrested and makes the news wearing a Yankees jacket?

“It was a pretty good tongue-lashing in front of the executive committee,” White recalled. “It was embarrassing, but over the course of a few months, we prevailed.”

While Beckerman signed deals in professional baseball, basketball, and hockey, getting past the gatekeepers at the NFL was another matter. The NFL had existing deals in place with vendors and manufacturers, and also a severe allergy to change. He tried the traditional method of buttering up the secretaries with coffee and donuts, but couldn’t even get a meeting with Bello, let alone a license. The pastry deliveries continued every three months, like clockwork, for eight years. He was in the elevator at NFL headquarters making another quarterly delivery in 1982 when the doors opened and Bello stepped on while chatting with an associate who recognized Beckerman.

“That’s the guy with the jackets,” the coworker said.

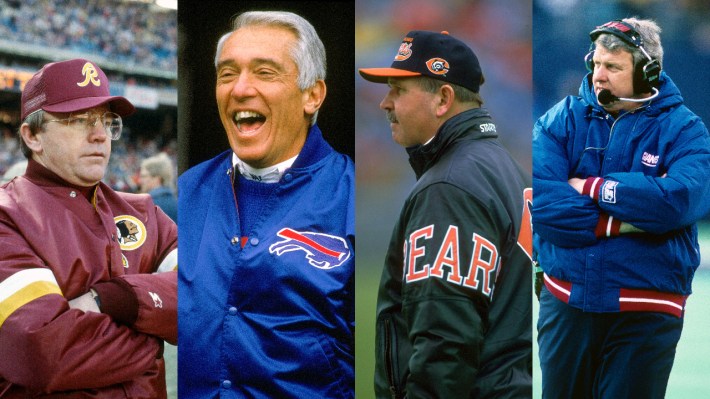

Beckerman made a literal elevator pitch on the spot and got his long-sought meeting, and an agreement was reached for Starter to create team jackets for the sidelines while receiving exclusive rights to use the league’s shield logo. A couple of years later the NFL launched Pro Line, which offered to fans a complete catalog of sideline apparel worn by players and coaches. This accomplished two objectives: It offered product to customers who wanted to wear what their favorite teams were wearing, and it created a sideline uniformity at a time when coaches ranged from sartorial to sloppy.

“The coaches at the time were either in a shirt-and-tie or in polyester crap that nobody would want to wear,” said Frank Vuono, whom Bello brought on at NFL licensing in the mid-1980s. “Back then, you wouldn’t want to get near a coach with a match.”

After New York Jets head coach Joe Walton was clothed in a team sweater and cap for a 1987 Monday night game, the league office received over 5,000 phone calls from fans asking where they could purchase the items, according to a March 1992 Sports Illustrated article. The floodgates opened. Between 1987 and 1988, MLB—now under the leadership of pro-commercialism commissioner Peter Ueberroth—the NHL, and the NBA created their own lines of authentic apparel. Leagues partnered with players unions so athletes could ink direct endorsement deals with manufacturers, with Starter signing Larry Bird, Dwight Gooden, and a young New York Giants linebacker named Carl Banks.

“We had no statistical data and anyone who tells you otherwise is making it up but, certainly, the people in the stadiums weren’t all kids and, my attitude was, adults would just as soon show their affection and affiliation for their NFL teams,” said Vuono, a former college football player at Princeton who remembers lamenting that he couldn’t get New York Giants sweatshirts as high in quality as what he had been issued as a collegiate player.

“No one in their right mind expected a 45-year-old adult would dare put on a jersey and walk around like that,” said Rick White, who was instrumental in the creation of MLB’s Diamond Collection. “Everyone thought it would just be silly, but it happened.”

Boy, did it. According to that Sports Illustrated article, the NFL’s manufacturers sold over $2 billion in licensed product in 1991, with Pro Line bringing in 30 percent of that number. Within four years of Major League Baseball creating the Diamond Collection, league properties were generating approximately $2 billion in business, with a quarter of that coming from authentic products.

It was a gold mine for Starter, which had expanded its product line as Beckerman was realizing the company didn’t need to limit itself to just jackets.

The company created hats and t-shirts that were distributed in locker rooms after championships, then offered those to fans at local sporting goods stores mere hours later. They created one of the first flex-fitted caps, added hoodies and, to carry all of this around, duffel bags. Starter’s sales increased from $58.9 million in 1989 to $124.6 million the following year, then $356 million the next.

Peter Nicholas, who wasn’t even sure he wanted the Pittsburgh territory when it was offered in the early 1980s, grew his revenues from around $100,000 annually to $25 million at its peak. Around the same time, Steven Seltzer acquired the Philadelphia region and was disappointed to learn it only earned around $200,000 a year. By the early 1990s, Seltzer’s region had boomed to around $35 million, with the salesman hiring a half-dozen reps and two office assistants to handle the workload.

“We couldn’t get them fast enough,” said Gary Adler. “And honestly, they knew it. I couldn’t get the jackets out of the box fast enough. I couldn’t even put them on the rack. It was wild.”

This period gave rise to the “fashion fan,” customers buying gear just because of a team’s colors. Teenagers nationwide were suddenly wearing Charlotte Hornets jackets because the color teal was hot. Atlanta Falcons hoodies began flying off the rack because the colors scheme matched a teenager’s new Jordans. Vuono got wind that they were onto something big when, on his work commute from New Jersey into New York, he would see hundreds of kids on their way to school in Starter jackets and hoodies of all colors and sizes. Seltzer would watch his son play high school basketball and half of the opposing squad would arrive in jackets he was selling.

“[Fashion fans] were a good chunk of the business,” said Stu Crystal, who handled marketing and sales for Starter from 1989 to 1997. “If the San Jose Sharks logo was cool and teal and black was hot, it didn’t matter if hockey was playing or not.”

“If you got the jacket, you got the hat to match,” said former NFL quarterback Donovan McNabb, who as a teen asked his mother for a Chicago Bulls parka and received an Anaheim Mighty Ducks coat instead. “For the African-American culture, it was something that was style. It was something that was us.”

Although it wasn’t the team he asked for, at least McNabb’s coat fit. At 6-foot-11, there weren’t many jackets that young Marcus Camby could fit into, so his Los Angeles Raiders parka had sleeves that crept up his forearms.

“I had to have it,” the 17-year NBA veteran said, adding he also owned New York Giants and 49ers coats. “Growing up, that was the thing to have. If you had a Starter jacket, you were really somebody.”

With Starter as one of the lead wagons heading into the Wild West that was sports apparel in the late 1980s, Beckerman needed to hire staff. He wanted creativity and passion in his applicants more than he cared about experience. He moonlighted as a high school basketball coach so he was looking for “coachability”; he directly instructed staff so frequently they started calling him “Coach David.” What he really sought was energy, an ingredient that might be more critical than anything in order to keep up with a founder who never seemed to rest. This was a guy who postponed his own wedding to meet with his first salesman because that was the only day the representative was available. He routinely flew out on Sunday nights and spent four days on the road, then came back into town and caught up in the office over the weekend. He would wake up in the middle of the night with an idea and fire off a call to an employee’s office phone, leaving a message so he wouldn’t forget.

Many of the new hires were recent college graduates that had a passion for sports and for this new company. They were young, they were scrappy, and they were driven. “We were a bunch of young kids working our butts off for this company because we loved it and we became a family,” said Kari Cunningham, who persistently sent resumes to get into the company and then worked in premium sales from 1992 through 1998.

Starting time was 8:30 a.m. but it wasn’t uncommon to come in 45 minutes early to get a jump on messages or paperwork in a pre-internet era, then spend the morning collaborating on a project or working the phones with customers or suppliers. The rest of the day might be spent assisting in the warehouse or with customer service. Most didn’t dare leave before Beckerman, who clocked out around 6:30 in the evening. On Friday after work they’d head to an employee’s house for dinner or across the street to Malone’s for a couple of drinks – but don’t drink too much because you’re probably pulling on some sweats and heading back into the office Saturday morning to tie up some loose ends.

“We were inseparable but, because of that, you never wanted to let people down,” said Bill Alfano, who worked in marketing for the company from 1992–98. “It was like a pickup baseball game when you’re a kid. It was the teams with your friends and, even if you didn’t want to do it anymore, you did it because you didn’t want to let people down.”

“I hesitate to use the word ‘cult,’ but it was really a different and special environment,” Beckerman said.

The company implemented a guerrilla marketing campaign with “influencers” before the concept was popularized, with Beckerman’s son, Brad, fostering relationships with musicians and celebrities and doling out clothing for the exposure. As a result, Beckerman’s young new staff never knew who was going to be on the other end of the phone when it rang. Evans answered once and Peter Cetera, lead singer of Chicago, was on the line looking for a jacket he’d seen on television. Actor Michael Madsen got ahold of him another time looking for jerseys. Alfano, who’d talked his way into a Professional Teams Coordinator position while still living at home as a 23-year-old, fielded calls from Jerry Glanville and Mike Ditka in his parents’ kitchen.

That’s to say nothing about the celebrities who popped into the office. One week, Emmitt Smith would be making the rounds, and the next it’d be Karl Malone. Bob Felice has a photograph of himself with ‘90s child R&B group and brand ambassadors Kris Kross. Beckerman walked into his customer service department one day to find his employees sitting on the floor, being serenaded by Boyz II Men.

Maybe this is common in New York, but this was 80 miles up Interstate 95 in New Haven, a town more famous for its pizza than its pizzazz.

“One thing that I remembered was that nobody left,” said Alfano. “Unless someone’s spouse got a job or there was an emergency, very rarely were people getting taken away from Starter—and we were getting offers. You had to be there. We knew without knowing how special it was to be there.”

Every coach has their mantra that former players always remember, and Coach David wasn’t any different.

“Shortage creates demand,” they all quoted, which was usually followed by laughter.

Beckerman realized that if everyone had his product, eventually no one would want it. He kept quantity curtailed, first by controlling how many stores sold it then by manipulating how much those retailers received. He was notorious for slashing order amounts in half. He wanted the stores unhappy, recognizing that something difficult to purchase creates more buzz than something overflowing off the racks. In exchange, the retailers received brand exclusivity since Starter put its merchandise in only one or two stores per area, if that. Felice recalled delivering about 60 percent of an order to an urban Philadelphia retailer. The next time he dropped in, he expected to be scolded, and was thanked instead.

Beckerman also hit upon the idea of cutting the amount of product manufactured in the first place, creating limited-edition coats that would sell out and never be seen on racks again. “He was the king of taking an item, making a select amount, selling those units out and not bringing it back and moving onto the next idea,” Marcy Silverman said.

One day, Nike founder Phil Knight got the idea to show up unannounced in a pair of sunglasses to inquire about purchasing Starter. He would eventually make an offer as he showed Beckerman around Nike’s Oregon campus. Although multiple former employees speculated that the offer was $400 million in Nike stock, Beckerman declined to provide details and a request to interview Knight through Nike’s communications team was not returned.

“It was a considerable amount of money,” Beckerman allowed. “I would rather say to you that the opportunity to secure security for my family and their family for the rest of their lives was never in question.”

He turned Knight down. He was a New Haven guy, and this was a New Haven company. About a month later, he realized that he might have just seen the future of the business, and it was ominous for Starter. If Knight could fly into town and nearly buy his way into the company in order to gain a professional league presence, what was stopping Knight from buying his way directly into the leagues?

“You go public for only one of two reasons,” Beckerman told me. “You want to put money in your business or put money in your pocket. I wanted to make sure we were protected.”

To hedge against outside threats and bring an infusion of cash into the still-growing company, Beckerman took Starter public in 1993. By then, the company was a $356 million operation, up 26 percent from the previous year. Crystal now had to spend a chunk of each day turning down requests from current and former athletes looking for a hook-up on shares.

“There was a vibe of, I’m working at a fun place and we’re going to be really big,” said Crystal. “The world is my oyster. We’re going to keep growing and we’re all going to get rich. And then it changed.”

The IPO in January 1993 raised $98 million of capital, as the stock opened on the New York Stock Exchange at $21 a share and settled at around $24 by the close of the trading day. In August of 1994, Jack Tucker was announced as president of the company. With a Harvard business school degree and two decades of executive experience, Tucker was exactly what Beckerman thought the company needed: a bottom-line-oriented guy who would be an effective face for Wall Street. The move allowed Coach David to step away and actually coach, devoting more time to leading his Hamden Hall High School hoops team.

Under Tucker, the company became a lot more regimented, evolving from figuring things out on the fly to having a standard operating procedure for everything. Prior to going public, sales had charted based on annual figures because everyone recognized the biggest numbers were in the fall and early winter when football and the holidays were in full bloom. But fickle shareholders aren’t interested in watching a stock tread water for three quarters.

One Sunday when Kurt Evans was at Foxboro Stadium for that afternoon’s Patriots game against Miami, he was notified by the Dolphins’ equipment manager that head coach Don Shula wanted to meet with him. No big deal—usually it was to ask about placing a special order or getting a garment in a different size. But a few minutes before kickoff, Shula walked up to him and got directly in his face.

“What the fuck is going on with your stock anyways?” Shula asked.

“’Shortage creates demand’ was one of David’s favorite lines,” said Peter Nicholas. “When you’re public, that shortage thing doesn’t necessarily work for the stockholders.”

Some of the company philosophies were altered, with Starter opening shops in big retailers like Macy’s and J.C Penney along with continuing to service the roster of select sports retailers like the Adler chain and Champs.

“I always thought we were incredibly nimble and David had unbelievable foresight in decision making,” said Alfano. “Then it seemed like we got very bureaucratic and almost deliberate. I always thought we were a half-step faster than everybody else and then I think we just came back to the pack.”

They were also losing market share, as professional leagues began licensing anyone and everyone for outerwear. Starter, which for all intents and purposes had the authentic jacket market monopolized at the beginning of the decade, was suddenly competing with Logo 7, Apex One, Pro Player and others. Even worse, Starter had made such a ubiquitous product that jackets offered by any manufacturer were starting to be referred to as “Starter jackets,” as if it were a style and not a brand.

“Starter became a generic name for licensed jackets the way Kleenex is for tissue paper,” said Tommy White, who worked in management for 15 years until the company folded. “The only thing I fault the leagues for is, when you’re licensing you have to manage your categories. You can’t have five companies making the exact same product at the same price point at the same retailers. You just can’t.”

And then the papercuts really started, beginning with the Major League Baseball strike, which canceled the 1994 World Series. Sales for the league’s biggest licensee fell off a cliff as the players union and owners bickered through the holiday season and into the winter meetings, leading to the following season being delayed as well.

“We had no Christmas sales and we had no preseason sales for the 1995 season,” said Dan Gooley, who worked with professional and collegiate baseball teams. “Numbers were way down for everyone, all licensees, because the fans were upset. These guys walked out and now you want us to buy something special? Forget it.”

The labor stoppage was the first of three the company endured during the last half of the decade, with the NHL cutting its season in half with a lockout the same year and the NBA suffering a 204-day work stoppage that wiped out a chunk of the 1998–1999 season. For a company that considered game visibility to be its oxygen, this was now less a papercut than a dagger.

“It hurt us a lot,” said Felice. “We lost all of our television exposure and the loyalty of the fanbase.”

The evolution of product placement on NFL sidelines reads like something Ray Liotta would narrate. Companies originally paid a stipend to team equipment managers to dress the coaches in their outerwear. When the head coach caught wind the equipment manager was getting money for something he was wearing, endorsement money moved to the coaches. When the owners found out that the coaches were being paid to wear a jacket for the team they owned, guess who came calling with their hands out?

By the 1990s, the process was a lot more elaborate and costly—in all leagues. What had started as a modest five percent royalty fee on the wholesale price was growing, up to seven percent, then nine percent, then 11, and ultimately 15 percent by the end of the decade. In addition, Starter and other licensees were now mandated to kick in up-front costs for marketing and advertising. Beckerman estimated that he was spending $1 million annually on the NFL alone for marketing, which included signage and season ticket packages with about a dozen different teams. That’s on top of the $17 million he was paying in licensing fees.

“When you have a royalty of 10 or 12 percent that you have to put on your top line, that means you have to make a product pretty cheap or you have to take less margin for yourself, and that’s what happens with companies,” said Dan Raskin, who was vice president of sales for Starter for over a decade.

Ask Beckerman what changed most from when Starter emerged on the scene versus when the company closed, and he doesn’t have to search long for an answer. “It’s all about money,” he said. “It’s not about anything other than ‘How much money can we make from licensing?’”

What Beckerman calls greed, league officials call business. Yes, royalties and upfront money were getting larger but so too were league footprints, costs, and player salaries. Gone were the days when the NFL or NBA simply set up a schedule and handed out a trophy. Sports had become a year-round, worldwide operation with television stations like the NFL Network and NBA TV, websites, social media, and philanthropy missions.

“We wanted them to support these endeavors as we sought to grow the brand,” said David Stern. “It doesn’t seem as greedy and illogical as David makes it sound, but I understand his point. It’s expensive.”

“We understood the importance of branding,” said NHL Commissioner Gary Bettman. “We understood that we were all in a fiercely competitive sports and entertainment marketplace and, as eyeballs were getting more and more alternatives, we all had to make sure that we were getting the exposure that we needed to compete.”

Beckerman couldn’t control external forces, but when the founder who so valued the relationships he had with league officials got word that Jack Tucker hadn’t visited league offices even once since taking over three years earlier, it was an unforgivable sin. On Aug. 27, 1997, The Wall Street Journal reported that Tucker had resigned and Coach David had regained control of his company, with Starter having recently reported second-quarter losses of $4.7 million. As deficits mounted, Beckerman struck a deal with Bank of Boston on the debt, kicking in $11 million of his own money—roughly half of the outstanding amount—and was granted two years to turn around the company’s fortunes.

Meanwhile, the downsizing was underway. Bill Alfano and Kari Cunningham were let go with severance packages in 1998, Stu Crystal left to take a position with the Kangol cap company, and Dan Gooley returned to Quinnipiac to coach baseball—with Beckerman helping his old employee draw up a contract with the university.

“When we were going through layoffs, you could see that was going to be the end of it,” said Cunningham. “To see something that you worked so hard for, being there before we went public, and to just know that this institution was going away was just awful.”

“It was incredibly sad because it was the only job I knew; it was literally the only friends that I had,” said Alfano. “I got a really nice severance package, and David himself came to my going-away party. I even felt appreciated when I left.”

A few months into the loan deal, Bank of Boston, which was in the process of being acquired by FleetBank, requested Beckerman add in even more of his own money. He refused, citing the signed agreement, and prepared a challenge in court. But, he said, his attorney told him he had only a 60-percent chance of victory, and worse still, it would probably take two or three years and cost about $5 million in legal fees.

The guy who always seemed to have a vision for where the market was going couldn’t see a winning scenario. He dropped the suit, which led to that Monday meeting and Chapter 11. Starter had gone from on the field to out of the game completely.

After the bankruptcy and closure were announced, many employees headed to Malone’s to commiserate and ponder what was next. Some were so distraught they needed to be coaxed out of the building at the end of the day, with Coach David giving them one last pep talk. Kurt Evans, realizing he still had access to his company phone, fax machine, and email, headed back to his office to work his contacts. His first call was to Bill Parcells, who answered immediately.

“I already know,” Parcells said.

A few minutes later Evans’s phone rang. It was Daunte Culpepper. No, he hadn’t heard the news, but he did want more hats.

By the end of the 1999 MLB season, every team had switched to Majestic brand jackets except for one: the New York Yankees, managed by Joe Torre.

Starter wasn’t the only casualty, as most of the sports apparel pioneers of that era didn’t survive into the 21st century to compete with shoe juggernauts like Nike, Reebok, and Adidas. Sports Specialties, producer of the “script” caps, was sold in 1992 by the Warsaw family. Nutmeg Mills, manufacturer of t-shirts and ostentatious rugby shirts, was sold by the Jacobsen brothers in to VH Properties, which ultimately dumped its licensed apparel division. Only New Era, the official cap company of Major League Baseball, remains in business.

“People always ask me what went wrong. The market just changed,” said Crystal. “You’re at your peak and you have high guarantees and you’re paying $7 million a year to the NBA. No one knew what the hell to do and eventually had to close or sell.”

The Starter brand would be sold off, acquired initially by the Schottenstein family which owned Value City furniture stores. Five years later, the name was bought again for $43 million—by Nike, who took the company’s athletic clothing line and sold it in Walmart. “Shortage creates demand” was dead as a concept.

“To see it in Walmart was even worse,” said Cunningham. “That was never where David wanted it to be.”

More than two decades later, there still seems to be a bile within Beckerman. The way he grinds out the word “grrrreeeeeed,” first spelled out in an email in all-capital letters when I approached him on the subject, then emphasized even more in person. The disdain for how the price of entry continued to rise. How the leagues didn’t have a long-term vision for the products or the manufacturers and weren’t interesting in partnering. How Starter and companies like it helped these leagues by developing a line of revenue they never knew was possible, but became invisible when they were in need of a lifeboat. The leagues treated manufacturers the same way a coach would handle an injured player: next man up.

Worse, these were people he considered friends. When Beckerman needed to be lured to his surprise birthday one year at the Basketball Hall of Fame, it was David Stern who did it.

It’s more than enough to make a person bitter, but Beckerman insists he isn’t. “Resentment may be too harsh or naïve on my part,” he said. “It was strictly a transactional relationship. It wasn’t a personal relationship. When you have a personal relationship, there is an opportunity to say, ‘How can we help you?’ and that was never said. It was all transactional, and that was the only negative thing that really bothered me. Having a transactional relationship versus a personal relationship is something I recognize in the end, but I didn’t recognize it in the beginning.”

Beckerman transitioned into commercial real estate, where he has remained since, recently completing a mixed-use project at his alma mater, the University of New Haven. His contributions to the sports apparel industry were recognized in 2015 when he was elected to the National Sporting Goods Association Hall of Fame.

“I was pleasantly surprised because I’d been out of the business, and for them to contact me and put me in the hall of fame was really special because it said I achieved something of note,” Beckerman told me. “I couldn’t see myself in the hall of fame of body bags.”

The Starter brand has been going through a bit of a resurgence, with former brand ambassador Carl Banks reviving the jacket line a few years ago in a partnership between his apparel company, G-III, and brand owner Iconix, which bought it from Nike in 2007.

“To be honest with you, Carl and I wanted to bring the brand back not only because we thought it would trend but also as a tribute to [Beckerman],” said Kyle Sanborn, who worked for Starter from 1993 to 1996 before starting his own company. “He’s been an inspiration for me to be in this industry for this long.”

There’s also been a renaissance in vintage athletic apparel, thanks to eBay along with boutique stores that specialize in old-school clothing such as Laundry in Portland, Rare Vntg near Philadelphia, and Mr. Throwback in New York. Starter satin jackets that retailed for $80 new are now commanding four times that amount. The most popular items are rare coats or iconic ones, like the Miami Hurricanes jackets that 2 Live Crew wore, or the all-black Los Angeles Raiders ones sported by N.W.A.—usually bought by adults who weren’t allowed to have them as kids.

“There was a thrill and this risk associated with it that is gone now, so they can enjoy these things and still be in touch with their past, but now there’s a safety to it because it’s not something people are willing to kill each other for anymore,” said Laundry owner Christopher Yen, who said he averages a Starter jacket sale a day since he opened in 2019.

“That Miami jacket is nearly impossible to find, and that’s one of the higher-ticket ones that goes for a lot of money because you can’t get it,” said Casey Pitocchelli, owner of Rare Vntg. “I haven’t seen one for sale for under $300 in 10 years.”

In November 2019, the old employees of Starter held a reunion at a restaurant near the old factory, with nearly 100 people showing up to swap stories, catch up, and hang out. The Beckermans had already made their way down to Florida for the winter, so Bob Felice FaceTimed in his father-in-law. The phone got passed around like a rumor in a middle school, as the team shared memories, sang songs, and generally showed their appreciation for Coach David.

“I don’t really think he understands the impact that he had on our lives,” said Cunningham. “If he were to start something today, I would go.”

“I’m so happy it happened in my 20s when I didn’t know enough to know better and had the energy,” said Alfano. “But I’m also kind of bummed that it happened in my 20s because I have been searching for that work atmosphere my whole life after.”

Around the same time, Stu Crystal was in Pittsburgh doing a college tour with his daughter when they ventured into a Dick’s Sporting Goods and spotted a rack of new Pittsburgh Steelers breakaway jackets. He dragged her over and launched into a detailed explanation of how he helped with the design of that coat almost 30 years earlier, expecting her to be impressed by his creativity or even proud of her father being part of clothing history.

“Dad,” she said. “You’re really getting old when the stuff you did is ‘retro.”