This excerpt from Wheels of Courage: How Paralyzed Veterans from World War II Invented Wheelchair Sports, Fought for Disability Rights, and Inspired a Nation is published with the permission of Center Street.

Seventy years later, at the age of ninety-two, Gene Fesenmeyer could still recall details about the two rollicking road trips the Rolling Devils made in the spring of 1947.

Boarding a C-47 military transport plane with his teammates and flying up to the Alameda Naval Air Station. The police escort that shepherded the team into Oakland. Staying at Dr. Gerald Gray’s horse ranch in nearby Walnut Creek and being thrown into the pool by his teammates. Going to a nightclub, with a showgirl reserved for him, and watching comedian Redd Foxx, “the dirtiest, funniest sonofabitch we ever heard,” according to Gene.

And, last but not least, whipping the Oakland Bittners, one of the top-ranked basketball teams in the nation, in front of thousands of exultant fans. “We kicked their ass,” he said.

Dr. Gray’s personal connections led to the Devils making two trips to the Bay Area. First, he scheduled contests against two college basketball teams. Thanks to Corona Naval Hospital's association with the navy, the team flew in comfort in a transport plane at a time when commercial airlines were not equipped to handle travelers with paraplegia and their wheelchairs.

Courtesy of the family of Dr. Gerald Gray.

The Devils looked snappy in their satin uniforms and red jackets as they faced the varsity basketball team from Saint Mary’s College. The four steel pillars that flanked the sidelines at dimly lit Kezar Pavilion in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park didn’t slow the Devils’ full-steam-ahead, zip-jerk-spin offensive stylings.

They crushed the Gaels of Saint Mary’s, 28–10, with Winterholler chipping in sixteen. “Not our best game,” coach O’Connell sighed. “Why, ordinarily we roll up 30 or 40 points.”

“Those kids get around like in the dodge-’em concession out at the beach,” said Gaels football coach Jimmy Phelan. “And those chairs really took a beating...They figure the chairs can always be replaced; no taxpayer can object to this item!”

The Devils then ventured across the Bay to play the University of California at Berkeley, Dr. Gray’s undergraduate alma mater. Before 5,000 curious patrons at the men’s gym, they outpaced the Golden Bears, 35–19.

“We would have to play a number of games before we’d be able to cope with them,” coach Clarence “Nibs” Price said, “and then we couldn’t be sure of taking their measure.”

The Devils returned to Corona, where they reeled off seven consecutive wins against non-disabled teams before they again flew north. Their next opponent was the Oakland Bittners, the semi-pro team owned by Lou Bittner, a local tax and insurance entrepreneur. His namesake squad was in its prime, having won the American Basketball League championship in March before losing in the national AAU finals to the mighty Phillips 66ers squad.

Courtesy of the family of Dr. Gerald Gray

Lou Bittner’s players were older than the college boys—many of them had served in the war—and they were much more talented. Their offense revolved around Jim Pollard, a high-flying forward in the days when dunking the basketball was a rare occurrence. The “Kangaroo Kid” led Stanford to the NCAA championship in 1942 before powering the Coast Guard team from nearby Alameda in the Service League. (He later starred for the Minneapolis Lakers in the NBA and was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.)

The Oakland Tribune sponsored the Devils-Bittners matchup and set about hyping the contest with daily dispatches. Reporters at the newspaper employed linguistic gymnastics to explain paraplegia and wheelchair basketball to their readers. The sport was “designed to aid in the recuperation of veterans who are rigid from the waist down.” The visitors are “boys who didn’t ‘walk away’ when the war was over,” and are considered “the whirling dervishes of wheelchair basketball.” This game was the “vehicle cage championships.”

Wrote sports editor Lee Dunbar: “A number of people . . . look upon the Rolling Devils as a freak outfit playing basketball in a highly distorted manner. But if you think those lads from Corona can’t play the game you have another think coming.”

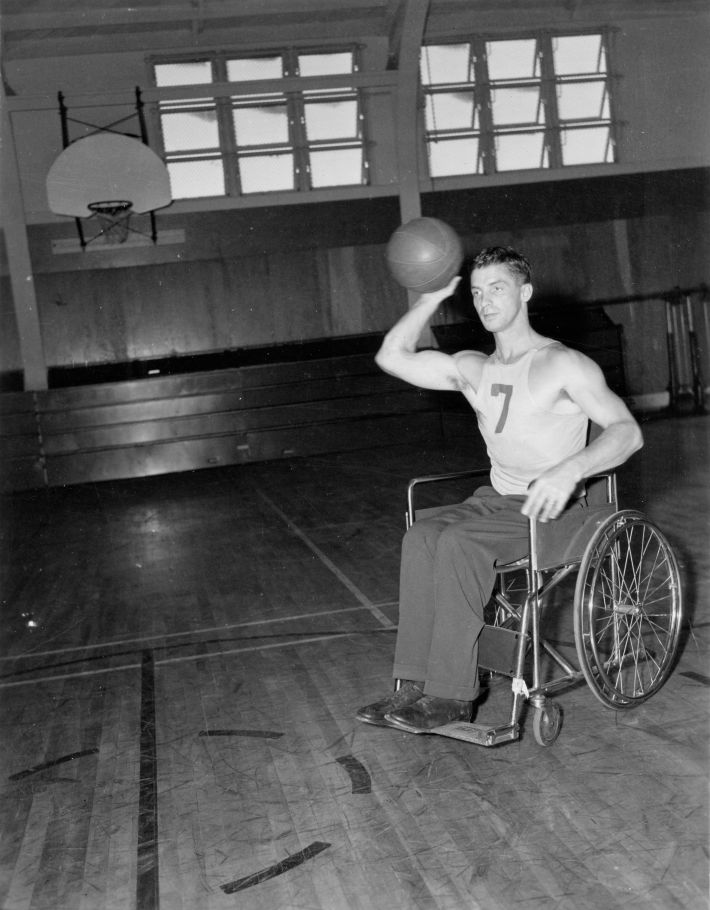

The Tribune printed numerous photos in the week preceding the game. Here’s Gene Fesenmeyer demonstrating the best way to pick up a loose ball while seated in a wheelchair. Heartwarming pictures of Lieutenant Louis Largey and his wife and daughter accompanied the story about how “Tank” was awarded the Silver Star and credited with more than three hundred kills in seventy-six hours during the battle at Tarawa.

Tickets for the 3,000 reserved seats at the Civic Auditorium were priced at $1.50, with general admission going for $1. Casey Stengel, the manager of the Oakland Oaks minor-league baseball team (who would parlay his success with the Oaks to land the managerial job with the New York Yankees in 1949), was chosen to assist the promotion by officiating a wheelchair free-throw shooting contest at halftime.

The Bittners were sent wheelchairs before the contest, and they practiced at the Athens Athletic Club in Oakland to mixed results. Players on both teams mingled at a pregame banquet and listened to Pinky Tomlin sing his smash tune, “The Object of My Affection.” The next day, the Devils were guests of Stengel’s in the ballpark as Casey’s Oaks, headed by aging outfielder Vince DiMaggio, beat their cross-Bay rivals, the San Francisco Seals, in Pacific Coast League action.

The basic question leading to the game was this: how would one of the best non-disabled teams in the world respond to playing basketball in wheelchairs? Coach O’Connell predicted an easy victory for the Devils. “We hope to give the Bittners the same medicine we handed to the Bonita All Stars last Wednesday in our 20th straight win,” he crowed. “Our offense wasn’t up to par, but the score of 31–5 indicates our defensive ability.”

Dr. Gray was equally confident, although more understated. “[The Devils] have too much experience on wheelchairs,” he said. “And besides, the Bittners will find the Devils are one of the best hustling teams they’ve met this season...Wouldn’t be a bit surprised if the Bittners remember them for a long time.”

On the night of May 26, a thunderous storm didn’t prevent some 8,000 spectators from making their way to the Oakland Civic Auditorium, hard by Lake Merritt, east of downtown Oakland. Many of those who stayed home listened to the radio broadcast on KLX.

Gene Fesenmeyer was primed. When the Devils were introduced, “I flipped my wheelchair up off my two back wheels, flew down the ramp from the dressing room onto the floor, did a couple whip-arounds and took a bow,” he later said. “Everyone went wild.”

Courtesy of the family of Dr. Gerald Gray

Before the opening whistle, a quartet of veterans who had been imprisoned during the war came onto the court to greet Johnny Winterholler. The four former POWs—Jack Stevenson, Earl Johnson, Ernie Lynch, and John Bridges—loomed over Johnny in his wheelchair, all of them beaming as they posed for photographs at mid-court. The sellout crowd rewarded them with a standing ovation. This was followed by the playing of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” with an escort of marines to present the flag.

Perhaps Winterholler, described as a “hunk of dynamite on wheels” with an “uncanny shooting eye” by Tribune reporters, was inspired by the pre-game festivities. His twenty-two-point onslaught singlehandedly outpaced Oakland’s entire roster.

Largey was the defensive star; he stuck to Pollard like a brand new product called Elmer’s Glue-All. The “Kangaroo Kid” managed two points, and the Devils romped over the Bittners, 38–16.

The wheelchairs were the great equalizer. It was the Devils who enjoyed unfettered mobility, moving freely and scoring at will, while the non-disabled all-stars were limited in their movements and frustrated with the results. The Bittners had “great trouble in steering their chairs in the right direction,” reported the Tribune. “When they took their hands off the chair it went in the opposite direction.”

Courtesy of the family of Dr. Gerald Gray

Fans felt sorry for the Bittners, recalled Gene Fesenmeyer. “They weren’t used to the chairs, and so when they got shoved they’d just tip over,” he said. “The crowd laughed like hell.”

Afterward, Mrs. Lou Bittner presented coach O’Connell with an enormous trophy. Net receipts of $2,800 went to the paralyzed veterans of Corona for the purchase of braces, wheelchairs, and crutches.

The Tribune produced a rousing fifteen-minute film about the Devils that highlighted their activities, social and athletic, during their travels. Shot in sixteen-millimeter with sound, the film showed the cheerful young men mugging for the camera and scoring on the court. The newspaper’s promotion department sent the movie to VA and civilian hospitals to publicize the sport and to boost the morale of others with paraplegia.

Wheelchair basketball was proving to be a potent elixir, both for the players and the spectators. They were the “No. 1 sports sensation of 1947,” according to Wyoming Daily Eagle newspaper columnist Larry Birleffi, while writer Elsie Robinson used her nationally syndicated column “Listen, World” to extol the Devils’ efforts. “It is one thing to stop a bullet and lie for months hospitalized,” she wrote. “It is another and infinitely harder thing to gather up the shattered fragments of your spirit and force them to quicken again. They had done all this and now they were out in their wheelchairs challenging America, licking almost every team they met.

“The real contest was a matter of spirit rather than of the flesh,” she continued. “We are given to doubt the American way of life in these bewildered times. But here was as fine an exhibition of clean sportsmanship and courage as America has known in many a day and here, invisible but triumphant, was the faith and decency that carried it on and that is our hope in the future.”

In almost no time, news about the emerging phenomenon of wheelchair basketball spread by word of mouth to paraplegia wards in other VA hospitals. Dr. Gray sent a copy of the rules to the paralyzed veterans at Hunter Holmes McGuire Hospital in Richmond, Virginia. Described by the Orlando Evening Star newspaper as “a far cry from mere arm-chair athletes” and a team for whom “legs don’t mean a thing,” the red-shirted Charioteers were soon defeating the likes of the University of Richmond’s varsity football team.

The VA hospitals in New York flourished as a wheelchair basketball hotbed. Two brothers who’d served in the marines, Al and Peter Youakim (the latter was wounded by shrapnel during the Bougainville campaign with the 3rd Division in the Pacific), organized a team among the paralyzed veterans at St. Albans Naval Hospital in Queens.

A team representing the veterans at Halloran Hospital on Staten Island recorded a string of victories against non-disabled clubs and prepared to take on the veterans at Cushing Hospital for East Coast supremacy. And, at the VA hospital on Kingsbridge Road in the Bronx, paralyzed veterans from ward 3-D wheeled into action as the Bronx Rollers.

When Gene Fesenmeyer and other vets from Corona were transferred to Vaughan Hospital in Hines, Illinois, they took the game with them. “We showed them how to play,” Gene said. “They started the team and seemed anxious to learn all the rules.”

The Hines Gizz Kids immediately reeled off twenty-seven consecutive victories against non-disabled opponents, including a win over Max “Slats” Zaslofksy and the Chicago Stags of the Basketball Association of America. The team’s unusual nickname derived from the slang word for the catheter that drained urine from the bladder and was considered a crucial element in the life-preserving treatment of paraplegia. Paralyzed veterans called the devices “gizmos” (pronounced with a hard “g”).

Naming themselves the Gizz Kids represented an inside joke at their own expense—and was another example of the coarse, sometimes profane, and deeply morbid sense of humor that many paralyzed veterans employed to cope with their condition. This was a way to “own” their disability, as it were, like calling themselves “crip” and “gimp.”

As they racked up victory after victory over non-disabled opponents, wheelchair basketball players were upsetting previously held notions of the limitations of paraplegia. Here they were, wheeling around basketball courts in front of the public and the media, not hiding away in some institution. Here they were, displaying athletic skills that were far superior to those of their non-disabled opponents. Here they were, traveling in an airplane and suffering no ill effects.

Their scrappy, take-no-prisoners attitude paralleled efforts away from the gym to take control of their fate and reintegrate into a society that was largely ignorant, apathetic, and downright hostile to the unique needs of people with paraplegia.

In the summer of 1946, a veteran with quadriplegia at the Bronx VA hospital named John Price began tapping out stories about himself and his brethren on a special electric typewriter donated by the Red Cross. The first issue of The Paraplegia News was a four-page newsletter with a simple motto: “A paraplegic is an individual.” PN quickly became the national voice and conscience for paralyzed veterans across America.

In the summer of 1944, Fred Smead was riding in a jeep in the small town of Torigni-sur-Vire in northwestern France. He’d landed on Omaha Beach in July and was chasing retreating Germans while on patrol with the 35th Infantry Division when a two-story building collapsed on the vehicle. The wall crushed three of his vertebrae and severed his spinal cord. He was eventually transferred to Birmingham Hospital, where he came under the care of Dr. Ernest Bors.

Smead became an outspoken advocate for the rights of paralyzed veterans. He scored an early victory when he traveled to Washington, D.C., and lobbied to correct an existing bill that allocated service-related compensation for hospitalized veterans. A veteran who was single, with no dependents, and a patient inside a VA hospital received only $20 per month (or $0.68 a day). Smead’s testimony pushed Congress to boost that allowance to the maximum amount of $360 per month.

With enthusiastic support from Dr. Bors, Smead and other patients at Birmingham decided to form a group exclusively for paralyzed veterans. They appreciated the existing traditional organizations that lobbied on behalf of U.S. veterans—including the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW), the American Legion, and the Disabled American Veterans (DAV)—but they wanted a separate, independent outfit that would address their specific concerns.

“Because we were so seriously disabled, we felt that the other veterans’ organizations could not give us adequate attention,” according to paralyzed veteran Gilford Moss. “In short, we would be swallowed up and forgotten.”

Lloyd Pantages, a discharged patient at Birmingham and the son of movie theater magnate Alexander Pantages, used his connections to persuade famed divorce lawyer Jerry Geisler to draw up the necessary documents for the group to incorporate. Paralyzed veterans around the country followed Birmingham’s example and, with prodding from Price, joined together in a nonprofit organization called the Paralyzed Veterans of America (PVA).

In February of 1947, the PVA welcomed some three hundred members from seven VA paraplegia wards to its first national convention, a three-day affair held inside Vaughan Hospital outside Chicago. Vena Hefner, who had been injured in a motorcycle accident while serving with the Women’s Army Corps (WAC), was the sole female attendee. Approximately thirty veterans with quadriplegia were wheeled into the gymnasium on beds to attend the meeting.

At its second convention, held later that year at McGuire Hospital in Virginia, the PVA forced the Hotel John Marshall to change its segregation policy and allow African-American veterans to attend the banquet.

Atop the PVA’s to-do list was obtaining government assistance for paralyzed veterans to purchase wheelchair-accessible homes, equipped with wide doors and hallways, ramps instead of stairs, and bathroom spaces and fixtures to accommodate their disability. The PVA also launched the National Paraplegia Foundation to raise money for medical research into spinal-cord injuries and diseases and to collaborate with doctors to find a cure for paraplegia.

These efforts, like those of the wheelchair basketball teams, would eventually benefit all those with paraplegia, including those who never served in the military. “With continued evidence of what a disabled man can accomplish, not only will many be given renewed hope and confidence, but the public, business and industry will be made to realize that the disabled— with a little help and understanding—can be useful, valuable and self-sustaining citizens,” Fred Smead later stated.

This excerpt from Wheels of Courage: How Paralyzed Veterans from World War II Invented Wheelchair Sports, Fought for Disability Rights, and Inspired a Nation is published with the permission of Center Street. It is available for purchase now.