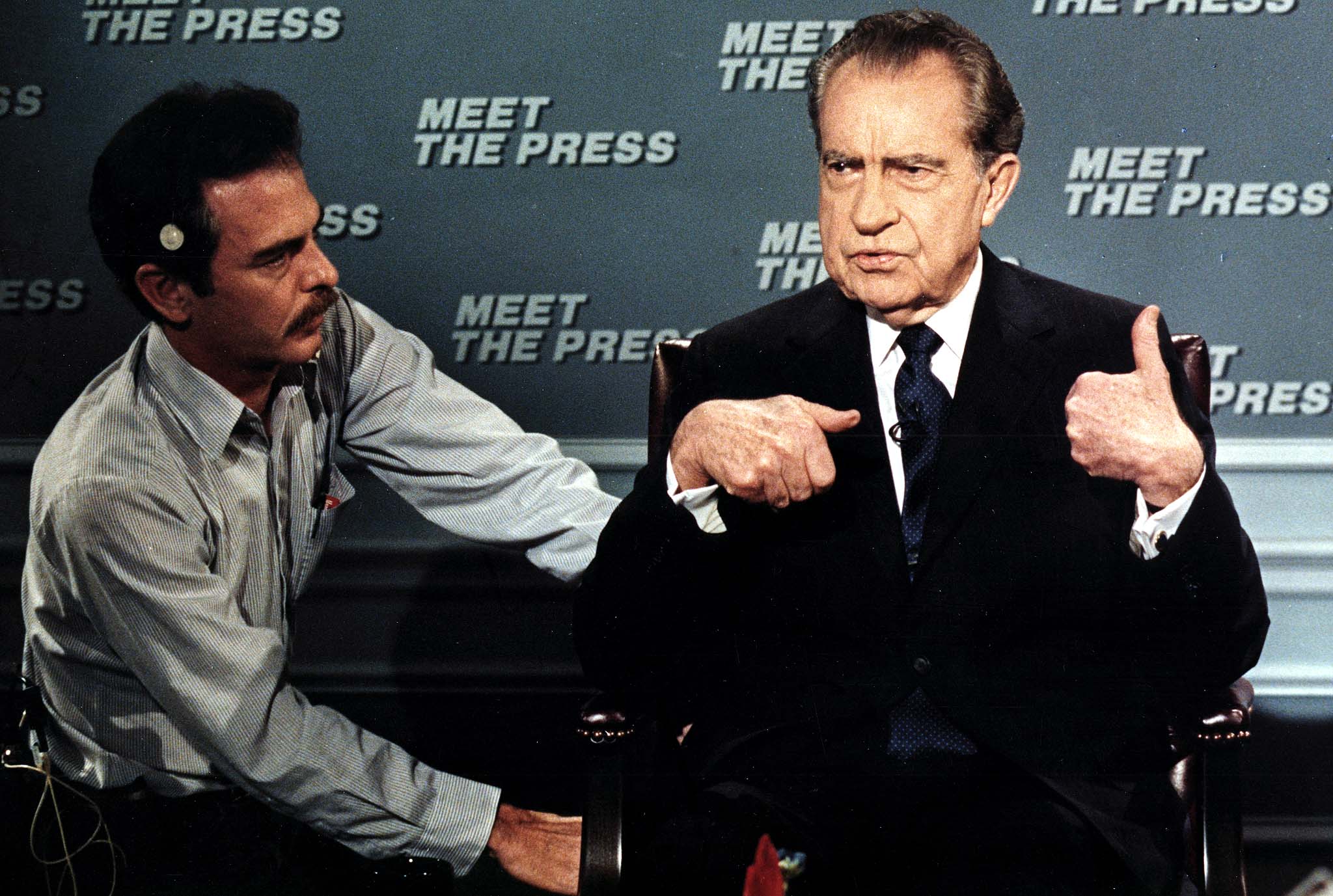

When he came off the mound on Sept. 30, 1988 after finishing off his eighth complete game and 20th win of the season, David Cone high-fived his teammates and walked into the home dugout unaware of what awaited him. Minutes earlier, as the ninth inning wound down, a fan in the stands decided that he was so thrilled with the All-Star’s performance that he just had to let him know about it, immediately. And so he did. Waiting for Cone in front of the tunnel to the clubhouse was not Cone’s pitching coach Mel Stottlemyre, nor a teammate lagging behind the line, but a former President of the United States. Looming in the shadows like Nosferatu, surrounded by his personal security service, with an outstretched hand and a burning desire to talk pitching with His Favorite Hurler, was Richard Milhous Nixon.

“It made you feel important,” David Cone told me, remembering his days on Nixon’s beloved Mets. “If these kinds of people are watching us or they care about us, it certainly made you feel that way.” If there was one thing connecting every player who came across the former President during the years he spent lingering in the orange seats of Shea Stadium’s lower deck, it’s that every one of them came away from their interactions feeling special. Not always good, exactly, but at the very least like someone whose job tossing a baseball was significant enough to win the attention of and an occasional handshake from Richard Nixon.

In perhaps the only scenario more intense than trying to wrap up a complete game, Cone suddenly found himself the subject of Nixon’s fascination. The former president congratulated him on his 20th win and told him what a joy he was to watch every fifth day. “I really didn’t know what to say at that point,” Cone said, sounding as if he was right back at that bottom step. “I remember saying something along the lines of him being our good luck charm, and You better keep coming out. It was the first thing that popped into my head, really. I was kind of floored by the whole thing.” They exchanged goodbyes and Cone went back to celebrating the highest point of his young career. Nixon, for his part, became another Mets fan riding the high of meeting one of his favorite players, and eagerly anticipating the next day’s duel between Sid Fernandez and Jose DeLeon’s Cardinals on the ride home.

The story of Richard Nixon and the New York Mets goes far beyond one uncanny interaction in the fall of 1988. As a matter of fact, it goes further back in time than the team itself. It could be argued that the Mets are one of the most accursed franchises in the sport; it is inarguable that, for the first half of the team’s six decades of existence, America’s most infamous president was a constant presence around the organization. Not that one has anything to do with the other, but it just seems worth pointing it out.

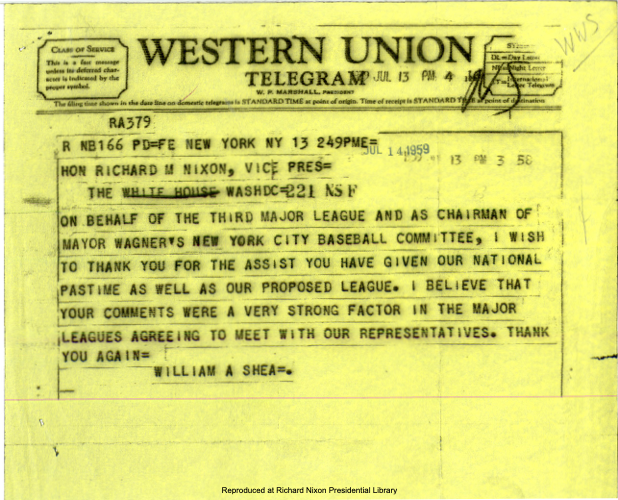

In 1959, after the New York Giants and Brooklyn Dodgers left for California, New York City Mayor Robert Wagner and a group of investors formed the New York City Baseball Committee. The goal was either founding the brand-new Continental League and a baseball team along with it, or snagging a team from the Major Leagues and giving them a new home. Some of the featured players in this group included future stadium namesake and power broker William A. Shea, Joan Payson, who would go on to become the first woman to own a major league sports team without having inherited it, and George Herbert Walker, uncle of George H.W. Bush. While a gaggle of wealthy New Yorker power players and the Bush family might have had enough pull to (hypothetically!) assassinate a president, that influence wasn’t quite enough to get the Cincinnati Reds or Philadelphia Phillies to take their offer to relocate. Left without much choice beyond cooperating with MLB, the group needed a figure with real influence to speak on their behalf and give them that final ounce of legitimacy. In the summer of 1959, they got their man in Vice President Richard Nixon.

In a telegram from Shea to Nixon, the man whose name still hangs high above Citi Field thanked the vice president for speaking to Commissioner Ford Frick and helping to persuade MLB to meet with the NYCBC representatives. Through those meetings, the Continental League was disbanded, Major League Baseball agreed to its first-ever expansion, and the NYCBC representatives were gifted a brand new team in New York City. In 1962, Richard Nixon’s foulest creation was born: the New York Mets.

For the first decade and a half of the Mets’ existence, Nixon was too busy being the leader of the free world and doing world-historic crimes to fully lean into being the Mets Freak he would become. Still, the two were never completely separate. In 1969, Nixon’s first year in the White House, the Mets streaked to a shocking World Series victory over the Baltimore Orioles in five games. Unfortunately, the practice of World Series Champions visiting the White House for clammy handshakes and weird photo-ops didn’t become standard until Ronald Reagan, and so there aren’t any pictures of Nixon and Tom Seaver talking shop. (Given Seaver’s heated opposition to the war Nixon was then expanding in Vietnam, this was probably for the best.) But while Nixon was never physically visited by the team, there was some correspondence between the two parties. This would continue, with some interruptions, until Nixon’s death in 1994.

Deep in the archives at the Nixon Presidential Library, there are few artifacts that connect the president to his victorious, rowdy baseballing sons. The first is a pair of letters, one from Mets General Manager Robert Scheffing giving the president a literal golden ticket to grant him admittance to any Mets game during the 1970 season; the reply is a letter from Nixon thanking the Mets for being remembered yet again with “another Gold Pass from the Mets.”

A special one-of-one gift, which was presented in March of 1970 by Commissioner Bowie Kuhn to “Baseball’s No. 1 Fan, President Richard M. Nixon,” is the crown jewel of the entire lot. Propped up in display box marked from the 1969 World Series are charms of Shea Stadium and the smiling Oriole logo, signed baseballs by each player on the Mets and Orioles rosters during the series, and what one can only assume was Nixon’s prized possession—a Mets 1969 World Series ring with his name engraved on the side. Few men in history had earned a World Series ring, and even fewer had ascended to the presidency. In the 12 months of 1969, Nixon did both.

The story of Nixon and the Mets hit a lull as the 1970s went on and President Nixon got busy becoming Luridly Disgraced Former President Nixon. But in the summer of 1979, the second chapter began. Retired from public office and ready to spend the rest of his years writing books and smiling politely in stilted photos with foreign dignitaries, Nixon purchased a condo on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. Meanwhile, New York baseball was at its highest levels of cultural relevance in decades. Unfettered by the responsibilities of office and safely unable to authorize any further bombing raids or Three Stooges-quality heists, Nixon was finally able to become the Baseball Sicko he was always destined to be.

As the title-winning 1986 Mets were constructed and deconstructed during the final years of his life, Richard Nixon was never too far from the players’ minds—or too far from them in general. When one of the team’s stars underperformed, or when a favorite player of his saw their time with the Mets come to an end, Nixon could be relied upon to send them a letter providing some form of comfort for the temporary issues or expressing his appreciation for the services the player provided for the Mets.

The dugout meeting was obviously David Cone’s most memorable interaction with Nixon, but it wasn’t the only one he would have during that 1988 season. After Game 1 of that year’s NLCS against the Dodgers, Cone "wrote" in a ghost-written column for the New York Daily News that starter Orel Hershiser “was lucky for eight innings” and closer Jay Howell “reminded (the Mets) of a high school pitcher.” That same day, Cone started Game 2 for the Mets and was tagged for five runs and was yanked in favor of Rick Aguilera before he could even take the mound in the third inning. Later that week, Mets public relations guru Jay Horwitz delivered a letter to Cone from that ghostly figure who greeted him in the dugout almost two weeks earlier.

“It was right on time.” Cone said of the letter, which he has kept to this day. “A handwritten letter of support saying, ‘We have a lot of confidence in you. Tommy Lasorda proved he could dish it out in Game 2, but you’ll have the last laugh in Game 6.’ It was a really nice letter after that controversy.”

Just as Nixon had predicted, Cone took the mound at Dodger Stadium in Game 6 and never relinquished it, pitching all nine innings while only giving up one run, getting the last laugh after a disastrous first outing and sending the series to a do-or-die seventh game. The Mets would end up losing that series, but the outcome didn’t change Cone’s view, even 34 years later. “I really needed that,” Cone said. “It couldn’t have been more uplifting or supportive. He really was a true fan.”

At his core, this was the Richard Nixon who spent his final decade hovering around the Mets like the benevolent but faintly menacing Ghost Of Metsies Past. He usually rejected the extravagance of sitting in Nelson Doubleday’s owners box in favor of being as close to the action as possible at the field level. By various players’ accounts, his interactions with them had less to do with being fawned over than with a sort of proto-WFAN caller wish to let his favorite Mets know that he really likes the snap of their curveball, or that even the worst batting slumps are only temporary when you’re Darryl Strawberry.

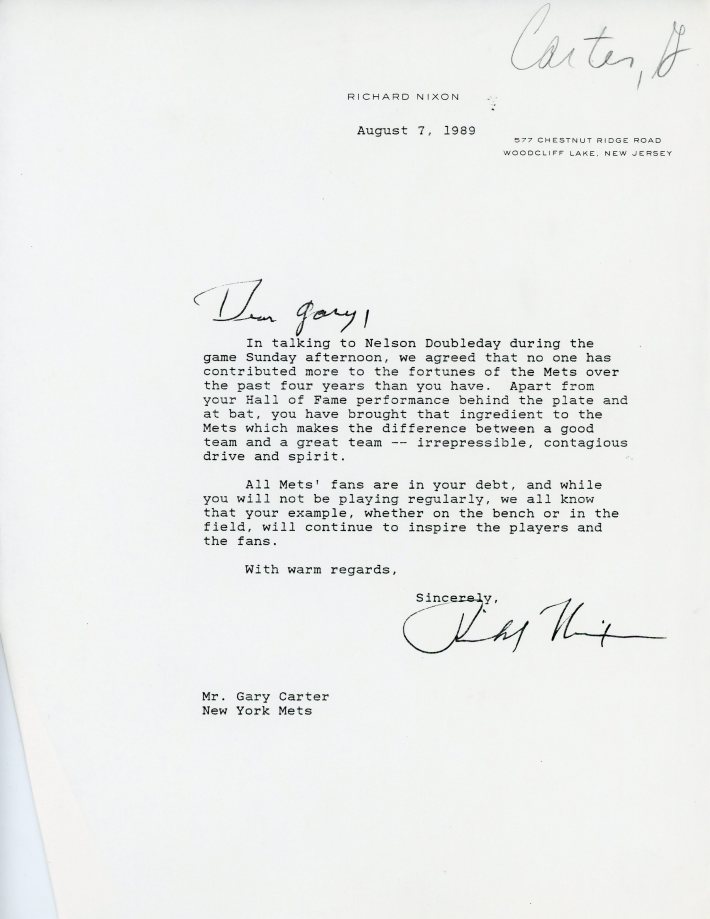

Through the Richard Nixon Presidential Library, and also in the homes of players he was particularly fond of, you can find a lot of Nixon’s kind words to that effect. In the possession of the Richard Nixon Foundation are a pair of letters addressed to Gary Carter in 1989. The first, written after Carter’s benching in August, describes the catcher’s “irrepressible, contagious drive and spirit” that was the special ingredient to the team’s success. “All Mets fans are in your debt,” Nixon writes, “and while we know you will not be playing regularly, we all know that your example, whether on the bench or in the field, will continue to inspire players and the fans. With warm regards, Sincerely, Richard Nixon”

Two months later, when Carter was released, a handwritten note was sent to the new free agent’s home expressing even more thanks and admiration. The president signed off by wishing the future Hall of Famer the best wherever he ended up, “even when you play against the Mets!”

Current SNY color commentator and 1986 World Series champion Ron Darling still keeps the letter and signed baseball that Nixon sent to him just days after his 1991 trade from the Mets to the Expos in his home library. Like any devoted fan of the team during Darling’s years with the club, Nixon bemoaned Darling’s “lack of support and too many no-decisions” as a Met before wishing him the best against every team but the Mets. “He had really become a sweeter person as he got older, I guess,” Darling told me. “It meant a lot to me that any former president would think that my trade warranted a beautiful note and a signed baseball. So it was very touching to me.”

Much like Cone and Carter’s letters from Nixon’s desk years before, Darling’s came at the right time and knew just what notes to hit in a difficult situation. Perhaps this timing was just luck, or a politician’s innate ability for ingratiation. But maybe as someone who (rightfully) faced the scrutiny and scorn of the American people and saw his approval rating tank to almost 20 percent before his resignation, Nixon understood what a few nice words could mean to someone at a low moment. Darling said that the president’s appreciation made him feel human at a time when he was dealing with the professional reality that he was a commodity that could be shipped elsewhere, even another country, when it was in his owner’s best interest. “You're at a crossroads in your career where getting traded is traumatic,” Darling remembered. “It really is. And anytime anyone reaches out and says, ‘Hey, listen, I know you got traded it's gotta be a strange time, but I just want you to know that you gave me a lot of joy,’ that really helps you get through the process.”

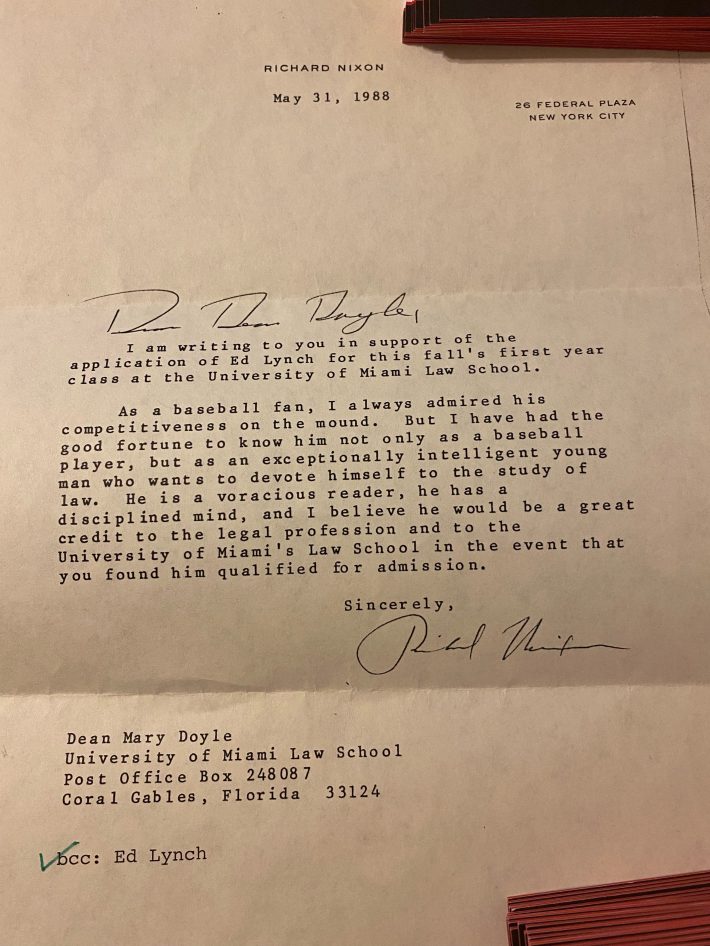

If the situation warranted it, Nixon wasn’t afraid of using his fame to do a favor for a player he was particularly fond of. Before he would spend six years as the Chicago Cubs general manager from 1994-2000, Ed Lynch was another Mets player who felt the uncanny impact of the former president’s presence. During the 1985 season, in one of Nixon’s many trips to Shea Stadium, he met Lynch; the two took a picture which would come in handy down the line. Lynch, like those who crossed paths with Nixon before and after him, was struck by the president’s dedication to the team. “It's like you’re a Centurion in the Roman army and here comes Julius Caesar,” Lynch told me, with a chuckle. “And he knows what you did in the last battle you fought. I mean, it's very flattering.”

Three years later, Lynch had been traded by the Mets, and bounced from the Cubs to the Red Sox and finally to the Giants. After a Mother’s Day start for the Triple-A Phoenix Firebirds in which he gave up 15 runs in 3.2 innings, Lynch decided it was time for him to go home to his infant daughter. “There was nothing there,” he said. “It was time.”

Back in New York, Lynch toyed with the idea of becoming a broadcaster, even meeting with Frank Cashen to discuss the trying-out process, but opted to apply to the University of Miami Law School instead. During a game he attended in his time back, Horwitz mentioned to him that President Nixon was in attendance. If he was interested, Lynch remembered Horwitz saying, he could take him up to pay a visit. Lynch accepted and was greeted by the always-formal president, speaking, as he remembered, “like a guy doing a bad Richard Nixon imitation.”

“I walked up and I said, ‘Hello, Mr. President’” Lynch recalled, “and he goes, ‘What are you doing now?’ and I said, ‘Well, I'm in the process of applying to University of Miami Law School’ and he said, ‘Would you want me to write you a letter of recommendation?’ And I said, ‘Absolutely, Mr. President.’ And I didn't think anything of it.”

A couple of weeks later, Lynch received a call from the University of Miami Law School admissions office and found himself on the other end of the line with a very agitated and confrontational staff member. “Sir,” he remembers the woman saying, “we frown upon practical jokes.” She sounded not just annoyed, but affronted, as Lynch recalls. “Well,” she went on, “we got a letter from Richard Nixon recommending you to law school and you know, we don't think it's very funny.” A stunned Lynch tried unsuccessfully to convince the caller that he actually did know President Nixon and that the letter, which attested to Lynch’s intelligence and love of reading, was authentic. Knowing that he was getting nowhere, Lynch asked the woman her hours and told her that he would be there tomorrow with definitive proof that he was telling the truth. That proof was the photo he took with Nixon three years earlier in the Shea Stadium clubhouse. Shown the photo that next day, the employees apologized. Lynch was admitted to the program, and would graduate in 1991. “I don’t know if the letter helped me or hurt me.” Lynch said, thinking back. “I think the reason I got in is that I could pay cash.”

Richard Nixon served his country as a congressman, senator, vice president, president, and national cautionary tale over the course of three decades. The last chapter of his life was less eventful. During those years, Nixon strenuously adhered to a Don’t Talk Politics Rule outside of formal settings, and so would rather spend an hour chatting about a nice comeback win over the Cincinnati Reds than anything even vaguely related to Vietnam, the Cold War, or Watergate. Though he acted as an elder statesman of sorts during those years, Nixon was by virtue of his own disgrace always slightly outside the ex-presidential community. The most notable events in his years out of office included visiting the Soviet Union and attending the funeral of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat as a representative of the country he once governed, but Nixon’s true passion post-resignation was a day at the ballpark and some good fundies on the diamond.

For Nixon as for the Mets he held so dear, things started to fall apart as the ‘80s turned into the ‘90s. His wife Pat’s health declined due to emphysema and the Nixons stepped away from public life and moved to Park Ridge, N.J. in 1991; a little over a year later she was diagnosed with lung cancer. On June 22, 1993, 53 years and one day into their marriage, Pat Nixon died with her husband by her side. Her funeral was held four days later at the Nixon Presidential Library in Yorba Linda, Calif. As he entered the garden for the ceremony, Nixon covered his face and sobbed. For all intents and purposes, that was the end of Richard Nixon’s life. He suffered a stroke at their home on April 18, 1994 and died in a coma four days later with his daughters by his side.

The last publicly available letter written and sent by the former President, to anyone, was mailed on June 30, 1993. Nixon was grieving, and in declining health, but not even that was enough to fully suppress the third affliction he was dealing with. In that letter, Nixon thanked Keith Hernandez, one of his favorite players and a former Mets captain, for a phone call while the president was mourning.

“She would have been so proud that you remembered her so thoughtfully and that makes me doubly proud.” Nixon wrote to the franchise icon. The 1993 Mets were a team so horrific that a book would be written about them called The Worst Team Money Could Buy. Those Mets were every bit the expensive and unlovable and utterly hopeless expression of an institution that had lost its way, a last-place team in every meaningful sense. They were also the last one Nixon would ever cheer for. The president ended his letter to Hernandez, the team’s former captain, with four handwritten words, underlining the third: “The Mets need you!”