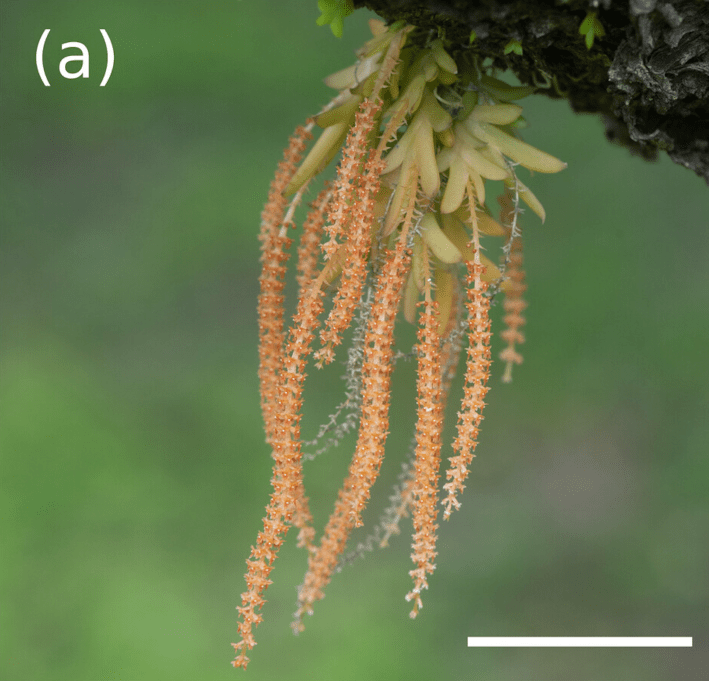

To the human eye, the blooms of the orchid Oberonia japonica are too small to even register as a flower. Instead, they resemble tiny orange discs with a white dot at the center, all whorling around an arched stem. "While it is possible to count the flowers, counting the petals is impossible," Yuta Sunakawa, a masters student at the University of Tokyo, wrote in an email. Each flower, at two millimeters wide, is about the size of the tip of a new crayon. All orchids in the genus Oberonia, commonly called the fairy orchids, are approximately this small. "They are, literally and figuratively speaking, overlooked," said Daniel Geiger, the curator of malacology at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History.

Scientists know that nearly all flowering plants on Earth cannot reproduce without pollination, in which an animal carries pollen from one flower's anthers and rubs it on another flower's stigma. Many orchids have evolved many complex, specialized adaptations to attract a single species of pollinator, which increases the chance that their pollen will go to another orchid of the same species. For example, the flower of the bee orchid resembles a female bee, luring male bees to copulate with the flower and inadvertently dousing themselves in pollen. When Charles Darwin observed the extremely long nectar tubes of the star-shaped orchid Angraecum sesquipedale, he predicted there must be an insect with an extremely long tongue-like proboscis that could sip on the nectar inside the flower, picking up pollen in the process. Darwin was ridiculed for this theory, but in 1903 scientists discovered a species of sphinx moth with a proboscis that fit the bill.

Now, more than 130 years later, "our understanding of orchid pollination remains limited," Sunakawa said. Scientists still do not know which species are responsible for pollinating more than 90 percent of orchid species. There are about 28,000 species of orchids, many of which are rare or live in places that are difficult to access, such as epiphytic orchids that grow high in the tree canopy. Fairy orchids present a different challenge: being so tiny that researchers need a microscope to see the pollinarium, the mass of pollen that attaches to an insect during pollination.

In the early spring of 2022, Sunakawa was wandering around a plum orchard in search of flowers when he stumbled upon the characteristic leaves of an O. japonica orchid that had yet to bloom. "Knowing that the pollinator was unknown, the site seemed perfect for observation," Sunakawa said. He returned to the site—with the permission of the orchard's owner—in May, alone, to see if he could observe any pollination in progress. He began searching the orchids at 10:30 a.m. Early in his observation, Sunakawa discovered a dead gall midge in one of the orchid's tiny flowers, with two pollinaria stuck to its head. When he touched it the midge came loose from the flower, still wearing its pollinaria hat. Sunakawa saw no other midges that day.

But at around 8 p.m., clouds of the flies began swirling around the flowers. "I stayed up all night, wandering the orchard, checking flower after flower with a red-filtered flashlight," Sunakawa said. Whenever he spotted an insect on the shiny leaves of a flower, he photographed it and collected it with a device called an aspirator (or a pooter) that allows scientists to collect critters that are too small to be picked up with forceps. Until 8:30 the next morning, Sunakawa checked more than a thousand flowers and slurped up more than a hundred midges. "It was hard work, but my excitement kept me awake," he added. He and colleagues published these observations recently in the journal Ecology.

Of the 128 gall midges Sunakawa collected, all 128 were female and about a third had pollen hats. Although this seemed abundant evidence that the orchids are effectively pollinated by the midges, the researchers still do not know what the midges get out of the arrangement. It's possible that the flowers could offer the midges a treat of sugar, oil, or protein, but the flowers were so small that the researchers "couldn't collect nectar from the flowers and aren't sure how to do so," Sunakawa said. Another possibility, the researchers suggested, is that the orchid's flowers mimic a posse of male gall midges or emit an alluring floral scent.

When people think of pollinators, they might imagine bees and butterflies. But many other species carry out this vital work, including bats, skinks, slugs, this one frog, and countless less charismatic insects like wasps, flies, and gnats. Much research on orchid pollinators focuses on orchid bees, butterflies, and moths, said Geiger, who reviewed the new paper. "But pollination in small-flowered orchids is little-known." Geiger wondered if Oberonia might attract pollinators with ultraviolet visual cues, as many flowers do. In a 2019 paper, Geiger used ultraviolet reflectance photography on the orchids to simulate insect vision. But he found Oberonia had no such cues, suggesting its pollinators were drawn to other sensory cues. "I postulated that small insects (gnats), which have much worse vision than bees, are the most likely pollinators of Oberonia," he said. The new paper's observation of midge pollinators confirmed his suspicions. "That is exciting, as it is one of the very few field observations on pollination in small flowered orchid," Geiger said.

Gall midges, also called gall gnats, are an extremely tiny family of flies that generally grow less than three millimeters in size. Many resemble tiny mosquitoes, but they are harmless to humans—besides their almost negligible size, they are often active at night. Some gall midges can reproduce in a truly bizarre process called pedogenesis, in which the immature larvae—maggots, if you'd prefer to be crude—clone themselves. But "little is known about pollination by gall midges," Sunakawa said. The researchers suggest gall midges might pollinate many more of these diminutive orchids. They might not be colorful, showy, or even really decipherable by the human eye, but to the orchid, the midges are just tiny enough to get the job done.