In 1951, 30-year-old Henrietta Lacks visited Johns Hopkins Hospital because she felt a painful knot in her cervix, where a tumor had been growing. Without Lacks's knowledge or consent, doctors shaved a dime-sized piece of tissue from her tumor and gave it to a tissue researcher. These cells turned out to have an extraordinary ability to double each day; other cells obtained from patients survived just a few days.

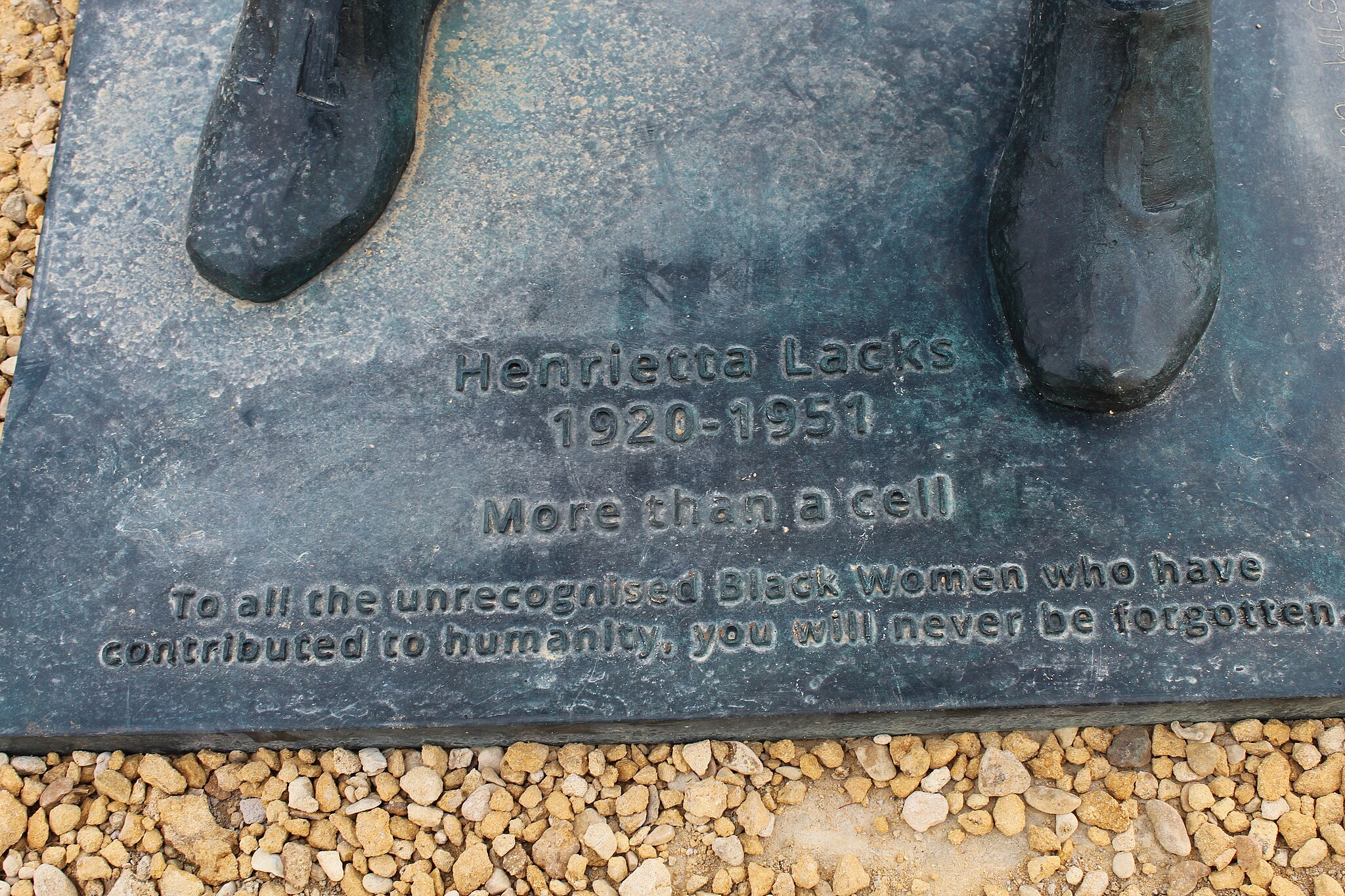

Lacks, a mother of five who loved dancing and painting her nails red, died later that year of cervical cancer in the "colored ward" of the hospital. Her cells became the HeLa immortal cell line—a biological workhorse that could be cultivated indefinitely and endlessly experimented on. HeLa cells underpin huge advances in modern medicine, including in vitro fertilization, vaccines for polio and COVID-19, and cancer research. In the following decades, it's estimated that more than 50 million metric tons of her cells have been replicated. But none of the companies that benefited from Lacks's cells shared these profits with her descendants.

On August 1, what would have been Lacks's 103rd birthday, her surviving family settled their lawsuit with the biotechnology company Thermo Fisher, which allegedly profited from the HeLa line while knowing the cells were extracted without Lacks's permission or consent. The lawsuit accused Thermo Fisher, which has an annual revenue of over $40 billion, of selling Lacks's cells in product lines such as Pierce HeLa Protein Digest Standard and T-REx HeLa Cell Line, without seeking approval from her family members or compensating them. The terms of the settlement are confidential. “It was a long fight, over 70 years, and Henrietta Lacks gets her day,” Alfred Lacks Carter Jr., one of her grandsons, said at a news conference on Tuesday.

It is impossible to say whether a settlement of any size could make up for the unfathomable contribution HeLa cells have had on modern medicine, and the years Lacks's descendants lived in poverty without health insurance. The settlement is historic: a long overdue step in addressing the wrongs in the racist history of medicine, a field that has frequently and brutally experimented on communities of color, as well as poor and disabled communities, in the name of scientific progress. But it should be seen as exactly that, just one step toward justice for both the Lacks family and the larger body of lesser-known people and communities whose bodies or genetic material have been exploited by science.

One of the lawyers for the Lacks family suggested they will likely pursue similar lawsuits against other companies that have profited off of HeLa cells, but their situation is somewhat singular. Reparations as concrete as this were made possible by an extraordinary situation: a settlement paid to known descendants by a company that profited off the cells of a single relative, who had become a household name due to Rebecca Skloot's bestselling book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, as well as the movie adaptation starring Oprah Winfrey.

What can justice look like for victims abused by the medical system who have no known descendants, or victims who will likely never be identified? How can the medical community imagine and advocate for communities who may have not individually garnered enormous profits but were wronged nonetheless? Consider the enslaved Black women who endured experimental surgery by J. Marion Sims, commonly called the father of gynecology; the victims of North Carolina's mid-20th-century sterilization program; or even, shockingly recently, the Black and Hispanic boys who were recruited to ingest the drug fenfluramine, which would later be banned for causing severe heart valve problems. "We need to go beyond individual restitution, to collective reparations," Camara Jones, a commissioner at the O’Neill-Lancet Commission on Racism, Structural Discrimination, and Global Health and former president of the American Public Health Association, told STAT News regarding the settlement.

Obviously the most meaningful justice would happen on a systemic scale. In 2020, Nature published an editorial calling for stronger rules governing consent in human participation in research. For example, the research community could revise the Common Rule, a set of policies in the U.S. that regulate participation in government-funded research, to require that anyone donating biological data provide explicit consent for their data to be used in research, even if that data is "deidentified" from them. The editorial also suggested researchers whose work builds on past injustices, such as HeLa cells or other unethically sourced specimens, should find ways to make amends. As Julia Craven and Margo Snipe explain in a collaboration between Vox and Capital B, some researchers are calling for health care reparations to repair the rampant inequities Black Americans face in healthcare and health outcomes.

HeLa cells were crucial in the discovery that the human papillomavirus (HPV) causes cervical cancer, the same type of cancer that killed Lacks. And HeLa cells paved the way in developing HPV vaccines, which protect people from a range of cancers. Now, if caught early, cervical cancer is highly preventable and treatable, yet Black women are almost one-and-a-half times as likely to die of cervical cancer than white women. Perhaps any company or researcher benefiting from the use of HeLa cells should direct some of those profits toward Cervivor, a group of patient advocates affected by cervical cancer that was founded by Tamika Felder, a Black woman diagnosed with cervical cancer at 25 years old, or the Henrietta Lacks Foundation, which helps people who contributed to scientific research unwillingly or unknowingly.

For now, Lacks's cells will continue replicating indefinitely in labs around the world and enabling more life-saving advances in medicine, as her descendants wish. But this settlement expands Lacks's legacy into a more philosophical realm. It opens up the gates for others to seek reparations for breakthroughs unethically extracted from their bodies, or for being a part of experiments they did not knowingly permit. Perhaps this is an equally immortal legacy.