Do you ever think about time? Like, really think about it? I do, perhaps due to a combination of ennui, depression, and the consumption of a whole lot of sci-fi novels. And it's the period of, say, between 100–1,000 years from now that I can't really get my head around. Shorter than that? No problem, that's just a lifetime, more or less. Longer than that? Nobody can really grasp "deep time," as John McPhee called it; I sure as hell don't expect to. But in between is this squidgy middle ground: still on a human scale, but not in the purview of any of us alive now. You can't make any rigorous predictions. You can't picture it. Life in the 1300s, for example is both immediately recognizable and still completely unknowable. I swear I'm not high. Given all this, I find something anchoring in the statement—and the optimism—that we know, specifically and surely, of one thing that will happen in the year 2640 C.E.

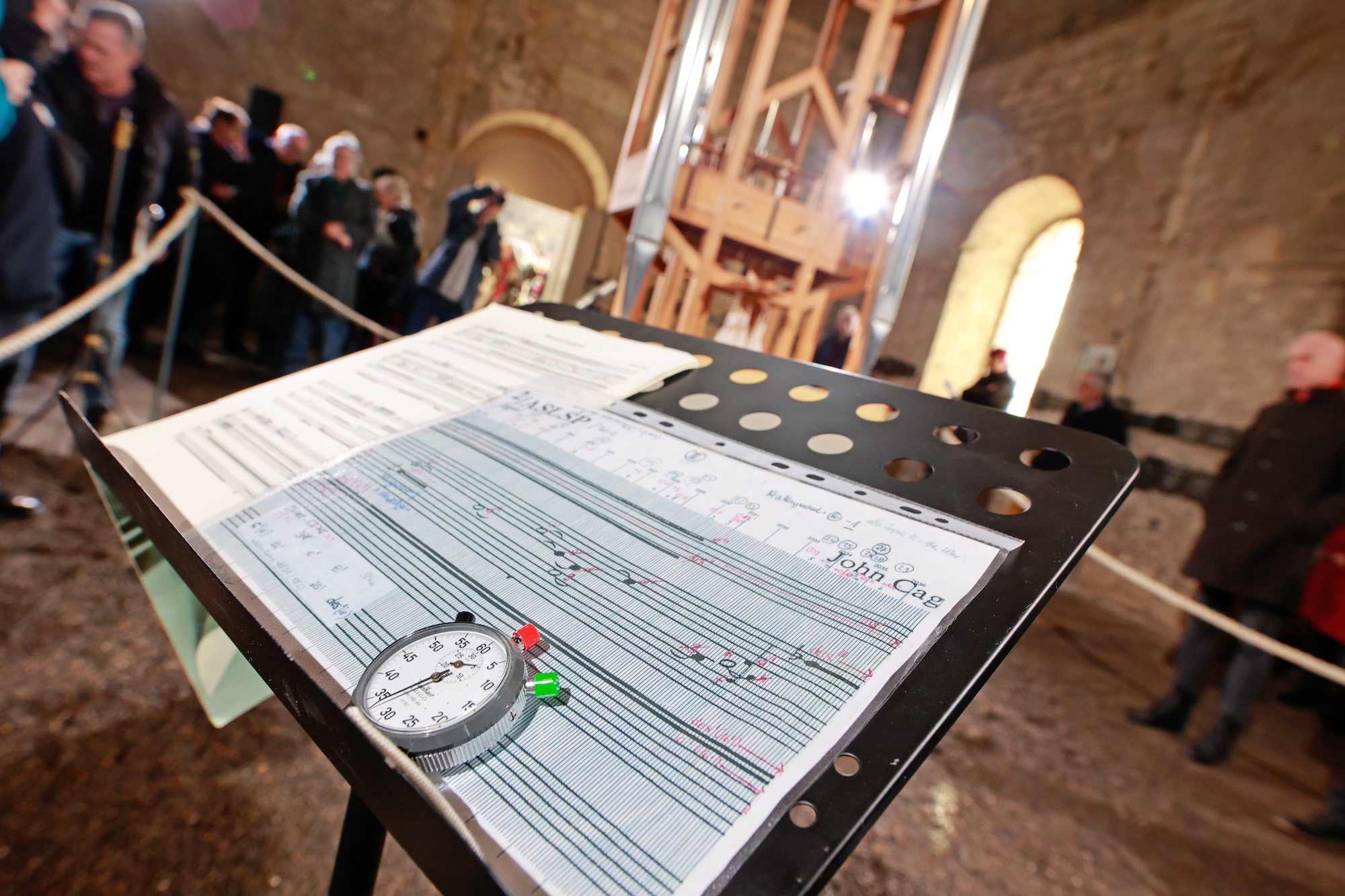

That year will see the last note of John Cage's musical piece, ORGAN2/ASLSP (As Slow as Possible), after 639 years of being played in a church at the foot of the Harz mountains in Germany. The song goes on and on, and has since 2003. Well, since 2001, technically: The piece began in silence, with a rest that lasted 17 months. Monday saw a chord change, the first in two years, and the 16th so far.

Cage, who died in 1992, was a prankster-philosopher, forcing difficult and provocative questions of what actually constitutes music. He is best known for 4′33″, a score that instructs its musicians not to play their instruments for the duration of the piece. It is a jarring performance to witness live—but it is absolutely not silence. You hear the sounds of your surroundings: in a concert hall, that's the soft shuffling of your fellow patrons, muffled coughs, your own heartbeat. It is the sound of, well, existence. Cage really cooked with that one.

So, when Cage declined to specify the length of As Slow As Possible (written in 1985 for piano, and adapted two years later for the organ), he knew exactly what he was doing. It has given the music world fits ever since.

"And they said, 'Oh, the organist must sometimes go to the loo or sometimes to eat,'" recalls foundation member Rainer Neugebauer. "And then one person—he was a theologian—said, 'No, the organist must play until he dies [in] the seat.'"

The John Cage Organ Foundation formed in Halberstadt with one goal: to put on the slowest, longest performance possible. They raised the money and constructed a special organ in St. Burchardi Church, one in which sandbags hold down the keys and the organ is constructed as the piece progresses—yesterday's chord change required the installation of a new pipe. This performance would last 639 years, to honor the installation in Halberstadt of one of the first Gothic keyboard organs 639 years earlier.

It has not gone without hiccups. The organizers misread the score and the 17-month rest that started the piece actually should have been 28 months. A chord change was delayed for a week to allow for a local dignitary's attendance. Once a documentary film crew accidentally bumped a pipe, changing a note for a few hours until an expert could be fetched. The piece being played is not exactly the piece Cage scored. No piece ever is, Cage might have pointed out. A performance is something entirely different than notation on a page. It takes place not in the mind of its composer, but in life.

A performance is also its audience, and As Slow as Possible has a devoted one. People come from all over the world to witness the chord changes, camping out for weeks to get a spot in the small church, or donating hundreds of dollars for front-row tickets. Tickets, by the way, are available for purchase to be there for the end of the final note on Sept. 5, 2640—and they are transferrable.

Therein, I think, lies the magic: The opportunity for concrete evidence that the world will go on after we're dead, something it can be hard to wrap the lizard part of the brain around. Perhaps a descendant of mine will witness the completion of this piece, or at least blog about it. Perhaps society will survive that long, in a form recognizable enough to maintain this performance without interruption. Wouldn't that be something? Forcing us to think on these scales, and offering hope that humanity can finish what we start, is the goal of many a project along these lines, like the Clock of the Long Now, which aims to keep accurate time for 10,000 years. You can get something like the same effect from planting a tree that you will never see grow to maturity. The world is bigger than us, and longer too.