Defector has partnered with Baseball Prospectus to bring you a taste of their work. They write good shit that we think you’ll like. If you do like it, we encourage you to check out their site and subscribe.

This story was originally published at Baseball Prospectus on October 12.

Here’s a little story you may not have heard about this year: It turns out that pitchers were using substances like Spider Tack to enhance their spin, and once MLB found out, they were pretty mad (eventually). They instituted a barrage of embarrassing inspections, leading to a precipitous falloff in spin rates and higher offense in the second half of the season.

Problem solved: Some supposed cheaters got caught; spin rates fell; offense returned.

Except.

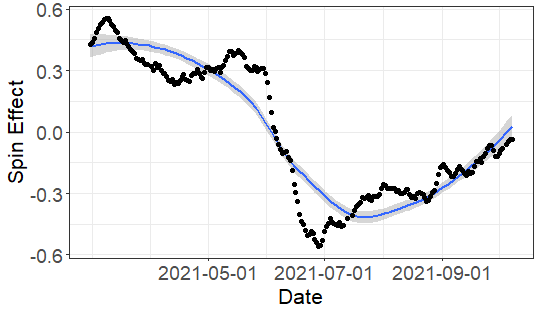

The most recent pitch data shows spin rates are returning to their former heights. After a brief-but-extreme reduction, pitchers have shown across-the-board RPM and movement increases since July. And although there are fewer ultra-high-spin pitches than in May, about half of the reduction in spin has reversed itself, with signs of an accelerating increase during the postseason.

Garnishing the ball with sunscreen, rosin, and other goop has been part of the game since time immemorial. But as recent investigative work showed, pitchers started turning to advanced substances, testing their ability to boost their spin rates with fancy cameras and other technology. Chemicals like Spider Tack–a glue body-builders use to grip heavy weights–can boost spin by hundreds of RPM, leading to material improvements in a pitcher’s stuff and ability to strike hitters out.

So MLB instituted a crackdown in June, leading to pitchers abandoning those substances. The effects were drastic, immediate, and severe; in a matter of weeks, pitchers lost as much spin as they had gained in the last three seasons. Strikeout rates returned to earth and hard contact increased.

Since that precipitous decline, spin rates should have plateaued at whatever the new normal is in a Spider Tack-less world. But that’s not what happened. Instead, they have risen: slowly, at first, and now with increasing speed.

This chart shows the effects on spin rate after neutralizing a host of confounding variables, like temperature, which players have been playing, and park effects. Even accounting for all those factors, spin rates have recovered drastically since July. Over half of the net reduction from May 15 (when spin began to fall fastest) has come back.

This trajectory is visible on the charts of individual players like James Karinchak. The Cleveland reliever was one of the pitchers hit hardest by the sticky stuff crackdown, losing about three inches of vertical movement on his fastball. In his most recent appearance, however, that trio of inches has reappeared even more suddenly than it evaporated.

A first and very reasonable thought is that players may have found ways to conceal the very substances that MLB outlawed in June. The inspections the league instituted—with umps checking belt buckles and hat brims—were sufficiently formulaic that a clever thrower might have been able to simply put their glob of sticky substance in a different spot to avoid detection. No amount of umpires feeling up players or causing them to disrobe was going to eliminate every potential route for pitchers to get something onto the surface of the baseball.

Though that is the most obvious possibility, there’s also a chance—a small one, in my estimation—that players found some way to adapt without breaking the rules. Perhaps all it took was a sticky stuff crackdown to get everyone to adopt seam-shifted wake effects into their pitch design, or pay more attention to their biomechanics in order to maximize their spin rates. I count this hypothesis as unlikely in part due to the speed with which spin recovered.

It took about three years for pitchers to iteratively design (and spread via clubhouses and whisper networks) better and better goops to put on the ball to cause it to move more and more; those three years’ worth of progress were erased in a month or so thanks to the crackdown. I just can’t imagine that players across the league discovered enough alternative ways to boost their spin rates in the last 60 days that it rebuilt years’ worth of progress. Necessity may be the mother of invention, but it would be a miraculous leap forward in pitch design to regain all that spin without any goop, especially considering the players are so busy on a day to day basis playing baseball at the highest level.

While spin has recovered since July, it hasn’t come back in exactly the same way. Specifically, there’s a category of fastball—those with spin-to-velocity ratios in excess of 28—that was common pre-crackdown, but went extinct when MLB instituted the inspections. Through April and much of May, these pitches were about 10 percent of all fastballs. But they haven’t returned even though average spin rate has increased, and the players who threw them most often tend to be the ones we know or strongly suspect used the extremely high-performing sticky stuff, like Spider Tack (hey, Gerrit Cole). The umpire crackdown has perhaps served as a nudge to those players not to go too far in their experiments with spin-enhancing substances, even if they are tacitly allowed to mix up a little sunscreen, rosin, dirt, and whatever else.

In part, the crackdown was more theatrical than anything else, a not-so-subtle message to the players like Cole to cut it out. For a brief moment, it looked like the league’s pitchers heard it loud and clear, but now, we’re well on our way back to the high-spin league we had through the first few months of 2021. What happens next will depend on what attitude the league wants to take to the epidemic of low-level cheating unfolding under their noses.

For about a hundred years, sticky substances applied to the ball were within the realm of often-accepted cheating; for about a month, it was heavily scrutinized and penalized. Without another aggressive push to limit substances, there’s every reason to believe pitchers will simply find more and better ways to skirt the rules, rather than actually abandoning the miracle goops that make them much better pitchers.