A now-disgraced male comedian (perhaps a redundant descriptor these days) once had a joke about the absurdity of civic pride that I think of often. The gist was that civic pride is stupid. Who cares where they’re from? More importantly, doesn’t the channeling of that pride through pageantry as American and manufactured as professional sports reveal something ridiculous, even shallow? This was a line running through my head for months after the Golden Knights made it to the Stanley Cup Finals during their inaugural season and Las Vegas seemed a city transformed—from a tourist destination known for sports betting and watch parties but no professional team of its own to a town bear-hugging the newest, most eye-catching thing that anyone outside the state would pay attention to.

The Golden Knights are recipients of the kind of local loyalty and exaltation that often stems from major success or unfathomable catastrophe. In the Knights’ case, it’s a little of both: The Mandalay Bay mass shooting happened just a few days before the Knights’ inaugural season began. The team held a tribute to the victims before their first home game, and soon the “Vegas Strong” motto became synonymous with the Knights, as it was often tied to the iconography of the team’s logo. Since then, Vegas has been overrun with every imaginable kind of Knights merch. In 2018, the San Antonio Silver Stars became the Las Vegas Aces, the city’s first WNBA team. In 2020, the Aces made it to the WNBA Finals, the same year the Raiders completed their relocation to Vegas. By the time the Aces won back-to-back titles in 2022 and 2023, Vegas was officially a sports town.

And the sports just keep coming: The city hosted a Formula 1 race and the final rounds of the NBA's new in-season tournament last year, the A’s have now begun a long and possibly doomed journey to Vegas, and this Sunday the city will host its first-ever Super Bowl. Becoming a city that’s home to multiple pro sports franchises and in the rotation for Super Bowl hosting is a strange development for Vegas, given its relative newness and depiction as an ever-adolescent wasteland. Vegas is for addicts and retirees. It’s the place where the notorious tagline—What happens in Vegas, stays in Vegas—originated, not as a pithy bit of common knowledge, but a slogan conjured up by the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority in 2003.

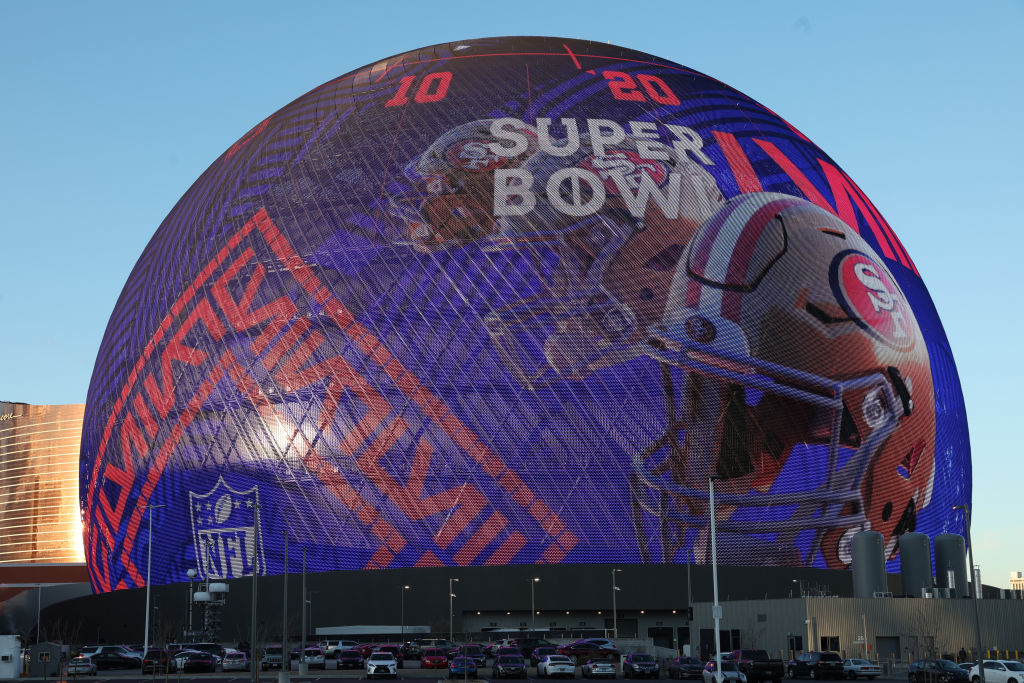

The steady arrival of professional sports teams and marquee sporting events, in tandem with wildly expensive real-estate speculation and the rapid construction of large-scale entertainment structures like the Sphere, has contributed to a common sentiment: that Vegas is now, at last, a real city.

The “realness” of Vegas looks a lot like the realness of any other major American city, which is to say, increasingly corporatized and expensive. I remember childhood afternoons in the backseat of my dad’s car driving down dirt roads that are now sprawling suburban neighborhoods and gaudy hybrid shopping-business plazas. This is predictable and disappointing, but also how I’ve usually perceived the city: a kind of glittering oil spill. Vegas’s expansion has been rapid, but the general flavor, the deep-down personality of it, has always been a little muddled. Until recently, the nostalgia-inflected stasis—dramatized as dystopia in Blade Runner 2049 and romanticized as fraternal honor in Steven Soderbergh’s reboot of the Ocean’s franchise—represented a nugget of truth in certain pockets of the city, particularly downtown. We had Elvis and Sinatra, but not necessarily at their best. We had Siegfried and Roy, before the incident. We had O.J. breaking into a hotel room to steal his own memorabilia.

None of this adds up to a cohesive picture of a place, which can be useful if you’re trying to reinvent a city’s essence from whole cloth, trying to make a lot of money, or both. When the NFL announced that Vegas would be hosting Super Bowl 58 and not New Orleans as originally planned, there was an air of inevitability to the whole thing. The 2021 Pro Bowl, later deferred to the following year due to COVID-19, had already been scheduled, and the 2022 draft was set to take place over the Fountains of the Bellagio. Toss in the 2018 reversal of the federal ban on sports betting and the subsequent diseased proliferation of mobile betting apps, and you have something of a domino effect, but instead of clattering tiles, one hears the chimes of billionaire bank deposits.

There is an argument, made most vociferously by the city’s politicians and image custodians, that all of this is good for Vegas. Half a million people are supposed to come to the city for the Super Bowl alone, and this is seen as a prime opportunity to show the world what Vegas has to offer. Growth signals health. More people have jobs. More money comes in for civic upgrades. Better schools, better teachers, better hospitals, better, better, better. But Vegas residents have lived in an entertainment-now-sports town long enough by now to know that such promises of economic growth are often hollow. Clark County’s budget is still reeling from the disastrous public financing scheme that got the Raiders’ stadium built, which goes a long way toward explaining why the state's teachers union is currently suing to prevent another $380 million in public funds being handed over the A’s for their proposed new stadium. There’s also the fact that all this public money is being shoveled into the furnace while the water is quickly running out of the Colorado River, with one researcher saying that the recent decision for Arizona, Colorado, and Nevada to enact voluntary usage cuts “buys us a little time” but does not solve the issue. Corporate greed also means that local labor groups like the Culinary Union have to fight tooth and nail to maintain the kind of material ground that won’t be deemed exceptional in five years when the next contract dispute arises, and the celebratory tenor sung by the rich assholes setting these machinations in motion is highly conditional.

In the weeks and months leading up to the Super Bowl, there’s been a strange sense that the game has already happened. Beyond the dozens of ads and billboards, beyond the posters for massive viewing parties, beyond the grumbling about construction and traffic, the city has felt both busier and quieter. There can be a palpable hum in Vegas when something huge is happening, the spiked adrenaline of rushing through a crowd on New Year’s spread across the whole city. There can also be an odd vacancy when something big is concentrated in one area. It’s easy for outsiders to forget that, at any given time, there’s some other insanely expensive and well-attended event happening in the depths of some hotel conference hall. The Super Bowl, a gargantuan event that will draw hordes of people but funnel them into very specific parts of town, feels distant in that respect. So too do the widely touted knock-on benefits of hosting.

It’s funny thinking about the inevitability of all this. I grew up without much envy for what other, bigger cities had, apart from an adolescent irritation that the bands I liked didn’t play shows here. More and more of those bands do pass through Vegas now, but the prospect of seeing them isn’t as tempting anymore. With the arrival of more to the city—more entertainment, more sports, more business—has come an accompanying tangle. Perhaps evidence of Vegas’s realness is the fact that now the city has become an obligatory stop, a jumping-off point, rather than an end goal. Even if future Super Bowls are held here, or really any other marquee event, it will have been the result of a concerted facelift that obscures or even erases the history and texture of the city. That’s not to say that the city was previously some hallowed jewel. It’s just describing the natural, sanded-down progression of whatever passes for novelty and innovation these days.

It’s certainly more useful to imagine Vegas as constantly in flux, without history or limit. But this is also why there are no longer any resources to conserve, only ration out. Change might be endemic to the city, its kitsch fruitful to mine for insights about the American project, but Vegas feels like it’s soon to be the site of an unfortunate, increasingly unavoidable crunch. That anxiety saddens me as much as the water question, the heat-during-the-summer question, and the infrastructure-for-a-rapidly-growing-population question seems to bore others. These are long-standing issues that have received a lot of air-time and column inches, such that when things finally do start to break down, no one will be too surprised or shocked. But maybe I’m being too pessimistic. In Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, Hunter S. Thompson writes about a “high-water mark …the place where the wave finally broke.” That was 1971, and it was in reference to an American Dream that curdled into a rotten but vivid and captivating wreck. Maybe that wave is coming back.