Ever since 1902, when a fossil hunter discovered some enormous fossilized legs and hips, people have argued about Tyrannosaurus rex—what the dinosaur looked like, how it stood and moved and ate, to what end it used its wee little arms, etc. and etc. They have argued formally by writing scientific papers criticizing scientific papers that, in turn, criticized other scientific papers, or informally by smashing their fingers into keyboards to say that a Tyrannosaurus with feathers looks "weird and gay." If any of the billions of T. rex that roamed the Earth in any given year more than 67 million years ago were alive to see this discourse, they probably would have weighed in by eating the arguers with their banana-sized teeth.

T. rex—whose name essentially translates to Tyrant Lizard King—never asked to be royalty. But at the time of its discovery, T. rex had the misfortune of being 1) big 2) scary-looking and 3) an unwitting symbol of one powerful man's racist, anti-Semitic, and eugenicist beliefs, qualities that helped destine it to become the most famous and most debated dinosaur of all time. Debates in science are normal and good, because they help improve the scientific process. But these debates can be confusing to anyone who doesn't already have a grounding in the subject and can leave the public attached to a certain interpretation of fossils that are incorrect. (For example, the dinosaurs called Velociraptor in the movie Jurassic Park actually represent Deinonychus, a cousin that was twice as tall, a taxonomic mistake that may have been inspired by paleoartist Gregory Paul's 1988 book that Michael Crichton cited as inspiration for his novel.)

In February of this year, three researchers, including Paul, published a bombshell paper in the journal Evolutionary Biology arguing that T. rex should actually be split into three species. In July, in the same journal, seven other researchers published a vehement refutation of the February paper—the first peer-reviewed dismantling of the February paper. Both papers made national headlines. "This is not the first debate among paleontologists as to whether a particular bunch of similar fossils actually represent one species or multiple species," said Darla Zelenitsky, a paleontologist at the University of Calgary who was not involved in either paper. "The species Tyrannosaurus rex is iconic so we are hearing more about it in this case."

Most paleontologists have sided with the rebuttal, believing that current evidence points to a single species of T. rex. Still, the first research group refuses to back down from its claims, even calling the refutation "paleopropaganda." This saga raised a lot of questions for me, and probably many other people. Is the debate settled? How can you tell if a fossil is one species or another? Should you even care? So I asked some wise people to share their thoughts on the T. rex species saga and what to take away from it all, and will now explain it to you as simply as I can.

Tyrannosaurus context

Tyrannosaurus rex is a species of theropod dinosaur, a group of dinosaurs that walked on two legs and had three walking claws on each foot, and which also technically includes all birds. T. rex as big as school buses roamed around North America from around 68 to 66 million years ago in the late Cretaceous period. Since the first T. rex was unearthed in Montana, scientists have found many more. T. rex "is represented by dozens of individuals and hundreds of bones," said Elena Cuesta, former researcher at the Paleontological Museum of Munich. Some specimens bear awe-inspiring nicknames like "Black Beauty" and "Titus," and some are called "Stan" and "Sue."

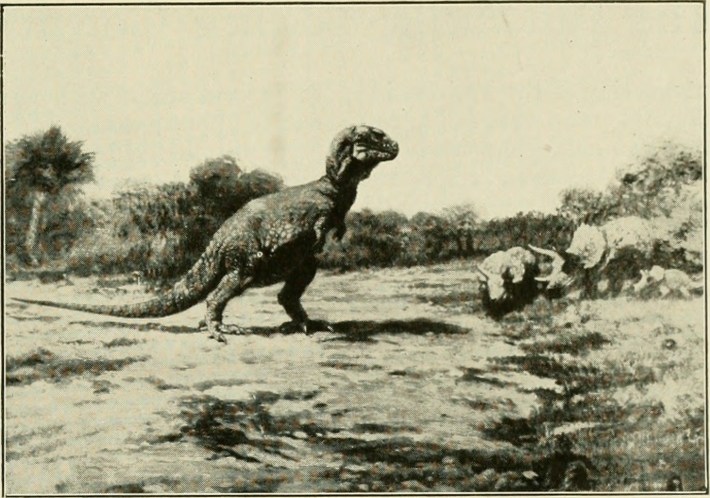

Each new specimen teaches us more about the species, and ongoing research has proven many of our initial assumptions were wrong. For example, the first T. rex unveiled to the public was posed standing upright with a dragging tail like Barney the dinosaur; scientists now understand the dinosaur must have walked with a horizontal spine, like a bird. This is why every specimen of T. rex should be open and accessible to scientists to reexamine old hypotheses and test new ones. But dozens of T. rex fossils are held in private collections, destining the bones to garnish a lobby of some undeservedly rich company or the house of some undeservedly rich person.

More specimens can also help scientists figure out if a collection of similar fossils came from a single species or more than one distinct species, which can happen as evidence accumulates. One of T. rex's favorite snacks, Triceratops, was described in 1889 and officially split into two species in 1996. Since T. rex was formally described a century ago, there have been "a huge number of studies about its anatomy, variation, ecology, phylogeny, paleobiogeography, etc.," Cuesta said. But scientists have generally remained settled on the idea that all specimens called T. rex represent a single species.

Tyrannosaurus wrecked?

In February, three researchers led by Gregory Paul, an independent paleontologist and paleoartist, published a paper in the journal Evolutionary Biology arguing that T. rex should be split into three species. The authors measured 38 specimens of T. rex, specifically comparing the girth of their femora (plural of femur, the more you know!) and the presence of two sets of chisel-like front teeth in the dinosaur's lower jaw. Although they found it hard to categorize certain fossils, they said 26 specimens fell into three groups. One group, found in the lowest and oldest rock layers of the Hell Creek Formation, had a stocky, "robust" build with two pairs of the chisel-like front teeth. The younger layers of the formation held two other groups of T. rex that had a single pair of chisel-like front teeth. One of these groups had bulky, more robust bones and the other had narrower, spindlier skeletons.

Paul and his co-authors proposed names for these three species. The oldest and bulkiest fossils would become Tyrannosaurus imperator, or "tyrant lizard emperor." The young and still-bulky bones would remain Tyrannosaurus rex. And the young, more slender skeletons would become Tyrannosaurus regina (pronounced like the head Mean Girl from Mean Girls), or "tyrant lizard queen."

The paper caused paleontological pandemonium upon publishing. Beyond the fact that it's weird to give a feminine name to the "slenderest" set of millions-year-old dinosaur bones—it's giving Skinnygirl®!!!—many other scientists said the study had weak, if not outright questionable, lines of evidence. "Most of the professional paleontologists that study theropod dinosaurs were carefully skeptical," Cuesta said. But the scientific process moves slowly, and so critics of the first paper were initially limited to sharing their concerns in tweets and interviews, making it relatively unclear to the public what, if anything, was changing about the status of T. rex.

Although many new stories explicitly called the paper controversial and aired much of the skepticism, the slow pace of science meant that no news story could conclusively say which scientists were right, and some stories that did not consult outside researchers gave an even vaguer impression of how the study was received by the wider community. And if the paper was published in a peer-reviewed journal, a reader without a scientific background might have inferred, how wrong could it be? All this could leave the average person confused as to where things stood with big ol' Tiny Arms.

Tyrannosaurus fact-checks

In late July, a team of seven researchers published a peer-reviewed open-access rebuttal to the first paper. The spicily titled "Insufficient Evidence for Multiple Species of Tyrannosaurus in the Latest Cretaceous of North America" aimed to make prehistoric mincemeat of the first paper. The takedown hinged on statistics, arguing that the first paper's evidence was too weak and inconsistent and relied on improper statistical tests.

The Paul et al. paper had broken the dinosaur into three species based in part on a finding that the T. rex specimens had unusually high variation in femur thickness compared to a group of other theropod dinosaurs, the logic being a single species would not contain so much variation. When the rebuttal compared the T. rex femora to a larger dataset of theropods including modern birds, they found T. rex actually has a very typical range of variation within a single species, variation that can be explained by growth and individual differences. And the original paper's statistical tests assumed there would be multiple species but never tested to see if the dataset really formed multiple groups, meaning the authors got the result they were looking for.

Moreover, the fact that the authors couldn't sort all the specimens of T. rex they examined into their three proposed species meant that their definitions were "extremely poor," Cuesta said. For example, the authors could not categorize the New York T. rex AMNH 5027, one of the most complete and well-preserved T. rex fossils, and which became the symbol of Jurassic Park franchise, because its skull is currently inside a glass case at the museum where it cannot be measured. The fact that this multiple species hypothesis creates so much uncertainty and confusion goes against the principle of taxonomy, Cuesta explained, which aims to make it easier to identify and assign unknown specimens into defined species.

The rebuttal also flagged issues with the specimens included in the original paper. "Almost half of the T. rex specimens they used in the original paper are owned privately or commercially," said Aki Watanabe, an evolutionary biologist at the New York Institute of Technology, who was not involved with either paper. The original paper included "Stan," who was recently sold in a private auction for $31.8 million to a buyer whose identity remains anonymous but can be narrowed down to someone who is not The Rock. Relying on so many privately owned fossils, which are not guaranteed to be accessible to all scientists, is generally "frowned upon in the dinosaur, or paleontology community in general," Watanabe said. This practice goes against one of the fundamental aspects of science, which is that studies should be replicable, he added.

The rebuttal was received warmly by the paleontology community, and the authors all reaffirmed that they were open to the idea of multiple species of T. rex, as long as there was sufficient evidence. In their eyes, sufficient evidence would require a sample size of at least 70 specimens, according to Thomas Carr, a paleontologist at Carthage College in Wisconsin and an author of the new rebuttal. "Given that T. rex is such a well-studied animal," said Ben Miller, an exhibition developer at the Field Museum of Natural History, "extraordinary evidence would have been needed."

Tyrannosaurus specs

Most dinosaurs are only known to the public as their genus names: Archaeopteryx, Triceratops, Brontosaurus, Velociraptor, etc. "Tyrannosaurus rex is one of the few dinosaurs where the species name, rex, is known," said Cass Morrison, a graduate student at Natural History Museum London and University College London, who was not involved with either paper.

The first thing to know, when discussing the difference between one species and another, is there is no universal definition of a species, but rather a bunch of different concepts that various scientists have proposed over the years. The most widely accepted is the concept of biological species—groups of organisms that breed together in nature to create fertile offspring—but even this has loopholes, like pizzly bears and wholphins as well as every organism that eschews sex for something even more thrilling, such as asexual budding. "Someone who doesn't work with taxonomy, they assume that we know how to identify species in modern animals, but actually it's more complicated than what we think," Watanabe said.

This species puzzle becomes much harder when it concerns fossil species, explains Asher Elbein in his great explainer on "the species problem." The infamous asteroid pretty much eliminated any chance scientists had at extracting dino DNA or even knowing what they looked like in real life—what colors or patterns may have rippled across the barrel chest of a T. rex. All that's left is the bones, which, in the case of many dinosaurs, may only be a single tooth or a part of a jaw. "If this sounds like dinosaur species are assigned based entirely on vibes, well, that’s partially right," Elbein writes.

And describing species with no DNA, no video evidence, and no complete skeletons means that species are frequently shuffled around and updated. "Reassigning and refining species designations happens all the time, and not just in paleontology," Watanabe said.

"I think it's unfortunate that taxonomy takes up such a huge part of popular discussion of paleontology," Miller said. "It really isn't very interesting."

For an example, pterosaurs (f.k.a. pterodactyls) are not technically dinosaurs. Pterosaurs are flying lizards called archosaurs, and dinosaurs are technically reptiles inside the clade Dinosauria. Dinosaurs have an empty hole in their hip socket and pterosaurs do not. But dinosaurs and pterosaurs still lived alongside each other in the same era of Prehistoric Lizard Earth, all looking like Prehistoric Lizards.

Before the Field Museum secured its T. rex star Sue, perhaps the most famous fossil to use nonbinary pronouns and to tweet, the museum displayed a smaller T. rex cousin, nicknamed "Gorgeous George." Over the past 30 years, this fossil has been labeled Gorgosaurus, Albertosaurus, and Daspletosaurus. "But it's the exact same skeleton, and the name on the placard doesn't change anything about how this animal looked, lived, or behaved," Miller said. "Where we choose to draw lines across the tree of life ultimately says a lot more about our esoteric system of naming and categorizing nature than it does about nature itself."

Watanabe and Miller reminded me that science is a process. Though the public might want black-and-white answers, "no paper is the final word on a topic," Miller said.

"The fact that it's not clean-cut is what fuels research in a way," Watanabe said. "It's supposed to be a self-correcting system."

But the first proposal has certainly posed a challenge to any would-be Tyrannosaurus taxonomists. "Having this idea out there though will surely have paleontologists combing the fossils for any such evidence that would indicate more than one Tyrannosaurus species," Zelenitsky said.

Tyrannosaurus next

So let's say scientists happen upon a windfall of new T. rex fossils and the evidence were strong enough to authoritatively split Tyrannosaurus into multiple species. What would happen next? In the eyes of the public, not much. "I don't think anything major would happen," Watanabe said. "I mean, the fossils still exist. I think at its core it's just like a name change."

Museums would have to update all their labels and graphics, video, and audio referencing T. rex, an update that is "more complicated than folks might assume," Miller said. Replacing a museum label is not as simple as a trip to Office Depot. "Say you have a big case with a graphic panel on the back wall, with several fossils in front of it, and something on the graphic needs to be updated," Miller offered as an example. "That means you need a glazier to open the case, trained object handlers to remove and reinstall the fossils, collections managers to track the status of the fossils, a graphic designer to redo the graphic, a printer to reprint the graphic, and probably more that I'm forgetting."

And what if the update isn't universally settled, or the science is still ongoing? Then it gets more complicated. At the Field Museum, one fossil went on display in 1907 labelled as the long-necked chunky herbivore Apatosaurus. But a 2015 paper determined the fossil could not be definitively referred to as Apatosaurus. "It could be Apatosaurus, it could be Brontosaurus, or it could be a unique species that doesn't have a name yet," Miller said. Until scientists take the time to reassess this particular specimen, museum staff have to label it as something. "Do we leave it as Apatosaurus? Do we call it 'indeterminate diplodicid' or 'unidentified sauropod dinosaur?'" Miller asked. "It's a judgement call where we have to balance accuracy with what is most helpful for our visitors." (The label remains Apatosaurus, for now.)

Tyrannosaurus flex

Now, to do my part in deflating the myth of journalistic objectivity, I will admit my bias. As someone who likes dinosaurs, I still feel like I am saturated with T. rex content even when I do not seek it out (everything I have learned about T. rex I learned against my will, etc.) So I asked some of the scientists I spoke with to tell me their true, unfiltered opinion of the most famous dinosaur in the world.

"That's a loaded question," Watanabe said, laughing. "I think T. rex has enormous potential, just like its body size, to bring people into science," he added. In this case, being the most popular dinosaur means it is also the most well-studied—the closest thing we have to a model organism for dinosaurs, Miller said. As paleontologists devise new ways to examine dinosaur brains, as they simulate how dinosaurs walked, ran, or crushed through bone, they apply these tests to T. rex first. "There was a time when I thought I was too cool for T. rex, that it was too mainstream," Miller said. "But after working on the Sue exhibit, I've been fully won over."

Yet, kind of like Nicki Minaj or MMA, T. rex comes with its own particular fan base, which Riley Black unpacked in an excellent Slate essay. Through no fault of its own, the dinosaur has become a symbol of toxic masculinity. When David Attenborough's dinosaur show depicted a T. rex doing more than killing, "it got into a British newspaper with people saying 'You're making T. rex woke because it's got feathers and is looking after the kids,'" said Morrison. (If you're now hungry for paleontological controversy, Morrison recommends Spinosaurus, the subject of a longstanding debate over whether it spent most of its time in the water like a penguin or waded in the shallows like a heron.)

So what have we learned from all this? Species are kind of fake. Scientists disagreeing with each other in a series of passive-aggressive rebuttals is part of the scientific process. Tyrannosaurus regina never personally victimized anybody, because she didn't exist. Putting together a Tyrannosaurus exhibit in a museum is hard work. T. rex fanatics need to stop using the word "woke." It's OK to stan a mainstream dinosaur. At the end of the day, we are all puny specks in the long history of our planet, and we would be lucky to be pursued and eaten by whichever Tyrannosaurus species deemed us a worthwhile snack.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story incorrectly referred to Deinonychus as Mongolian.