I could probably list every job I had since college if I was pressed to do so, although I mostly remember them in episodic moments, and not especially well at that. There are by now a couple of impacted decades of memories to go through—whole years of variously grim lunches and emptied-out hungover commutes and different rote tasks carried out in windowless rooms on sunny days—broken up periodically by periods of unemployment in which I wrote exceedingly mannered short stories and watched horror movies in the afternoon. I could tell you about many of those lunches and commutes and tasks, but I couldn't really say—could never, really, have said—how or why I wound up at one job or another. That wasn't really how my life went, in work or most anywhere else, for most of that time. I floated along until I snagged on to something, and stayed stuck there until the current picked me up and moved me along again. It felt like this even after what I had, or what I did every day, started to feel and look something like a career. Career, I think, is just what people call this sort of thing once they've been doing it long enough that not naming it starts to seem strange.

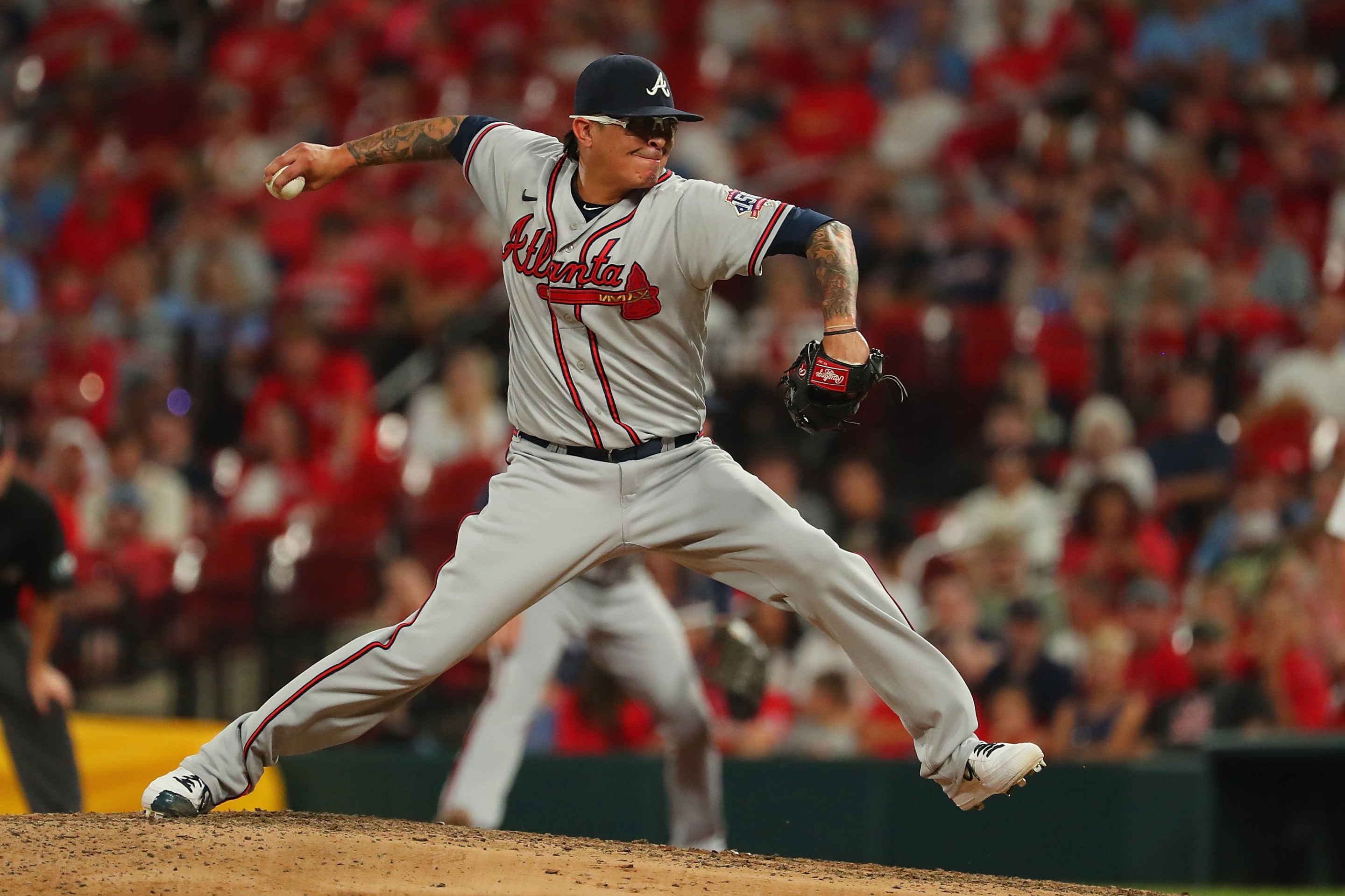

I want to make clear that I am not comparing myself or my career to Jesse Chavez or his career. We came into our respective workforces around the same time, and with a similarly negligible amount of fanfare—Chavez was first a 39th-round and then a 42nd-round draft pick; the second selection, in 2002, lined up decently well with the time I was fired from a temp job after one unremarkable day—but Chavez's job is both cooler and harder than mine. He has pitched in the majors in each of the last 15 seasons, generally effectively and always flexibly, both in the sense that he has been a starter and a reliever and also because he has constantly tweaked his approach. When he set a career high in strikeout percentage at the age of 34, in 2018, Baseball Prospectus noted that he did so after effectively ditching both his curveball and his change, which had previously been his two best bat-missing pitches. "While that was a previously unseen approach from Chavez," his note in the 2019 BP Annual reads, "it was also very much in character for a pitcher who changes his repertoire as often as his uniform."

Even by then, that was a lot. Chavez had played for nine big league teams by 2018, and had already been traded more than any player in baseball history. When the Braves made Chavez half of the return that they sent to Anaheim for Raisel Iglesias, it was the tenth time in his career that Chavez was traded. It was the second time he'd been traded this season. One of the stranger things about Chavez's career, and something that makes his Baseball Reference page a rich and compelling text to any sufficiently deranged reader, is that he has still just played for those nine teams. (He was on the Rays from Nov. 3 to Dec. 11, 2009; they traded Akinori Iwamura to the Pirates to acquire him, and then sent him to the Braves for Rafael Soriano.) When Chavez was dealt back to the Angels this week, it continued a trend in his career. Most of the teams that have employed Chavez have seen fit to employ him more than once.

This is something that Chavez has in common with his peers in the brotherhood of Extremely Well-Traveled Pitchers. The notable difference between Chavez's Baseball Reference page and that of, say, Jamey Wright, is both how Chavez changes teams (via trade, mostly) and the small number of teams that have spent the last decade of his career essentially passing him back and forth. The Pirates, with which Chavez made his big-league debut, only traded for him once (Kip Wells went to the Rangers; this was in 2006, and Chavez's first trade). So did the Royals (they sent Rick Ankiel and Kyle Farnsworth to the Braves in 2010, in exchange for Chavez, Tim Collins, and Gregor Blanco) and the Dodgers (they traded Mike Bolsinger to the Jays for him in 2016). The Rays had him in the organization for five weeks around Thanksgiving during Barack Obama's first term, although it must be said that they are very much a team that feels destined to employ Chavez again at some point in the future. If they do, they'll become the seventh big league team to acquire him twice.

The Angels just became the sixth team to do so. In 2017, when Chavez signed a one-year deal with them as a first-time free agent, he told the Orange County Register that the opportunity to pitch near his home in Southern California made a crucial difference. On the day that he signed with the team, Chavez told the Register's J.P. Hoornstra, he'd driven his kids to school in Pomona, Ca. "Being able to do that another 81 times was a luxury,” Chavez said. “It’s something that I couldn’t pass up.” (Another, more unusual facet of Southern California's appeal for Chavez can be found in an ESPN story from 2018. Chavez told Jesse Rogers that his wife worked as a longshoreman in Long Beach, Ca., logging her hours one day a month. "Finding a babysitter when she has to go to work is a big challenge," he said. "Her job is interesting. Scary. Very dangerous.") Chavez had played on travel teams with Ricky Nolasco as high schoolers in Southern California; the two were reunited in the Angels' rotation in their early 30s. Neither pitched especially well, the team went 80-82—the Angels are not about happy endings—and Chavez was gone again until Wednesday's deal brought him back.

He hasn't pitched for the Angels yet, but Chavez is having one of the better seasons of his career at 38. In 2018, Chavez told Rogers that he had already done most of what he'd set out to do. "You talk about the bucket list," he said. "You can keep it on five fingers. Get to your big leagues, get to arbitration, get to free agency, get to 10 years in the league. The ring is the elusive one." Chavez got one of those with the Braves last year, and he was unscored-upon in seven outings across the NLDS, NLCS, and World Series. There are still good innings left in his arm, and if no one knows quite how many of those there are, baseball has only ever invented one way to find that out. Chavez could, if he wants, surely find a job doing what he does—a new home, maybe, or just one of the many old ones he's already had. Or, anyway, "home" until some other team wants him more than his next one does, and then all this will happen again. It's a living, and this is how such a living is lived. All that life accumulates, change after change, names and places coming and going, until you can read some kind of story over it.