A woman in the stands at last week's playoff game between the Indiana Fever and Connecticut Sun wore a shirt that read “BAN NAILS.” She had evidently put some thought into this. The letters, blocky and unmistakable, were made from thick strips of duct tape. On both her hands was even more tape—a set of long, costume-like paper fingernails she could waggle around. At the risk of proving a new Godwin’s law, I’ll confess my first thought was “They’re eating the dogs, they’re eating the cats," because to parse any of this, you have to first be fluent in a foreign tongue of grievance. You must be steeped, irretrievably, in an imagined set of facts.

In Game 1 of that playoff series, the Sun's DiJonai Carrington tried to deflect a ball at the same time that Caitlin Clark lobbed it over Carrington’s head. Carrington mistimed her play, and clipped Clark in the eye instead. Replay review has conditioned fans to think slow-motion only reveals truths, but just as often, it obscures them, priming viewers to imagine actors with more time to act. A player falling to the ground looks to have flopped. A hand carelessly swatting at a ball seems aimed at a face, at an eye. “If you are assessing intent,” a psychologist who studied this effect told Slate in 2014, “never see the slow-motion version, ever.”

Neither of the two women on either end of the poke read anything into it, but a slowed-down clip circulating online gave the moment some juice. When USA Today's Christine Brennan asked Carrington whether the hit was intentional two days later, she said no. “I don’t even know why I would intend to hit anybody in the eye,” Carrington said. “But no, I didn't. I didn't know I hit her, actually. I was trying to make a play on the ball and I guess I followed through and I hit her.” Brennan pressed on: “Did you and Marina [Mabrey] kind of laugh about it afterwards? It looked like later on the game, they caught you guys laughing about it,” she asked, referring to an exchange between the two teammates where they pantomimed not a poke in the eye but Carmelo Anthony’s “three to the dome” celebration. “No, I just told you I didn’t even know I hit her,” Carrington said. “So I can’t laugh about something I didn’t know happened.” Clark was asked the same question and corroborated Carrington's answer. “It wasn't intentional by any means, just watch the play,” Clark said, chuckling, before leaving the scrum.

Somewhere on their journey to the internet, Carrington’s nails grew in length and treachery. Barstool Sports creep-in-chief Dave Portnoy asked why WNBA players were “allowed to wear gigantic nails if they use them as weapons?” Carrington’s nails, as captured in a Game 1 photo, looked short and unremarkable. Still, this all came back down to earth in the form of a woman taping “BAN NAILS” onto her shirt, just in time for Game 2.

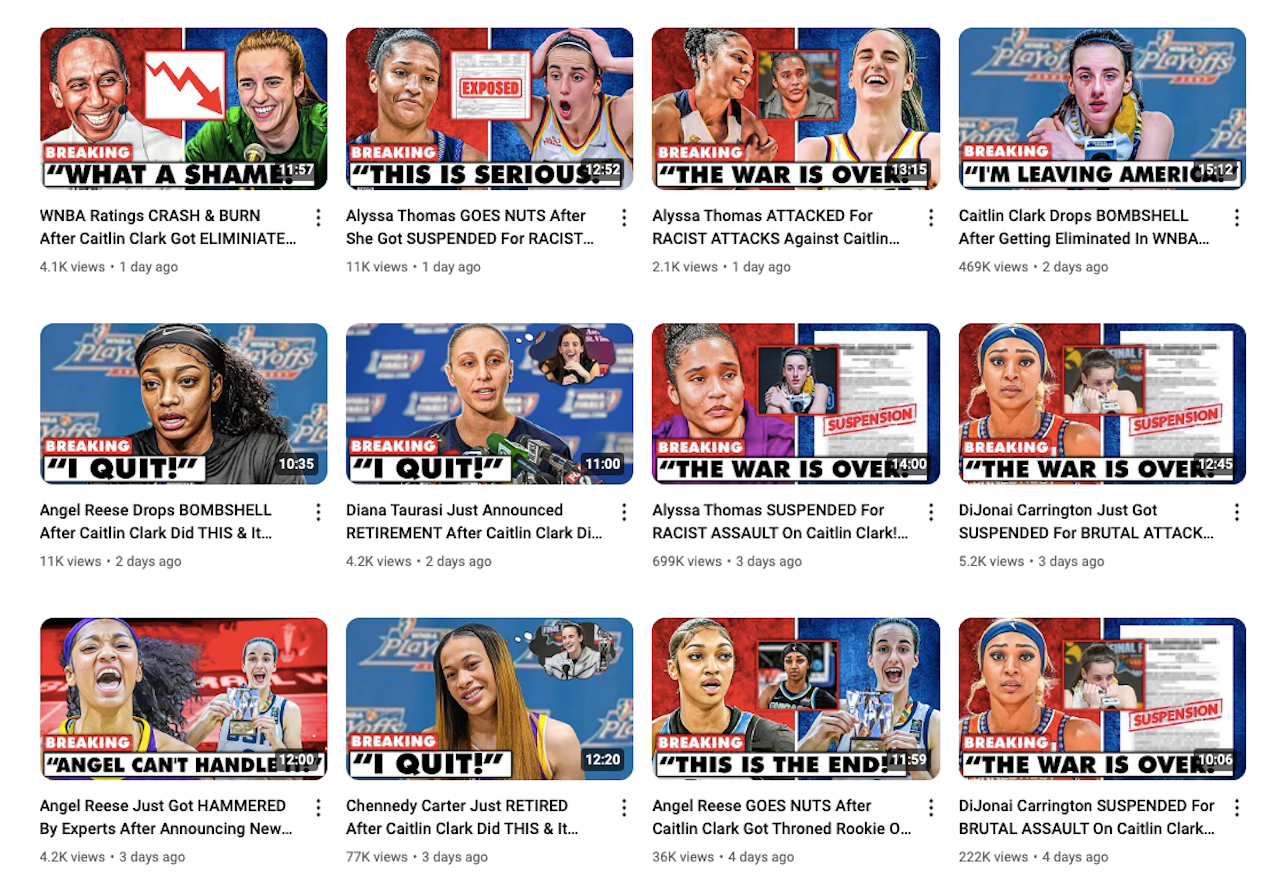

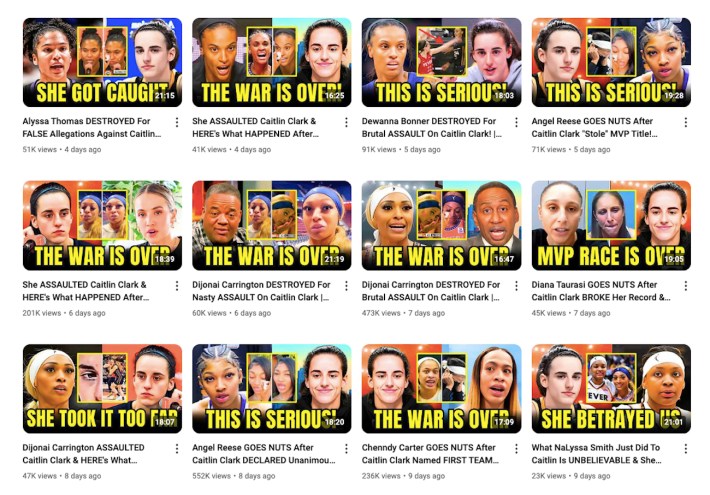

I thought of “BAN NAILS” earlier this week, while hunting for a video of the last shot Alyssa Thomas took in Sunday night’s Sun-Lynx game. The request I’d made of YouTube's search function wasn’t obscure or unreasonable, I thought. I just wanted to watch an important moment from a playoff game broadcast on ESPN, so I could embed it in the article I was writing. No luck. The first search result was a video titled “Alyssa Thomas SUSPENDED For Racist Assault On Caitlin Clark!” In the thumbnail, AI-generated tears fell down both women’s faces. A mock chyron announced, “BREAKING: THE WAR IS OVER!” The events described in the video’s title and description were totally bogus: Thomas has not been suspended at all this season, and the closest the two ever came to a physical brush was maybe a hard screen Thomas set on Clark in a game nearly a month ago. By the time this video was served to me, a person who had simply typed “Alyssa Thomas” into a search bar, it had more than 500,000 views.

In her excellent book Lurking: How a Person Became a User, the tech critic Joanne McNeil charts a sort of social history of the internet. The earliest, most optimistic visions of cyberspace—as a sanctuary, as something communal or collective, as the end of a search for belonging—gave way to a more corporate, extractive vision. As social networks chased hyperscale, people became “users.” On platforms with billions of users, McNeil writes, “there’s nothing designed to throttle a person motivated by malice from driving full speed into another person’s digital life. This clash between users is revenue: generating ‘impressions,’ the term of art for the number of views of a particular piece of content. If wide use is a company’s goal, harassment is not necessarily in opposition to that goal. Abuse, hate reads, coordinated harassment, and yes, outrage all lead to online rubbernecking—monetized clash.” Stopping the flow—imposing limits or attempting moderation—is bad business.

The phrase “monetized clash” came to mind in early September, when WNBA commissioner Cathy Engelbert joined CNBC to discuss the business of women’s basketball. One of the show’s panelists brought up the rivalry between Angel Reese and Caitlin Clark to ask Engelbert how the league responded when race and sexuality were “introduced” to the discourse. “How do you try and stay ahead of that, try and tamp it down, or act as a league, when two of your most visible players are involved—not personally, it would seem—but their fanbases are involved in saying some very uncharitable things about the other?”

Engelbert drew from her well of Deloitte-speak. WNBA players “sit at this intersection of culture and sports and fashion and music,” she said, before likening the moment to the NBA rivalry between Larry Bird and Magic Johnson. (“One white, one black,” she added helpfully.) When she offered that fans do enjoy rivalries, she almost seemed to be starting toward an interesting thought: Professional sports are essentially monetized clash, the costs primarily borne by players, the rewards reaped primarily by the league. But she never took it further. As for the social media stuff, WNBA players should just ignore it, Engelbert said. The answer was panned by several players and in a statement from the union. Engelbert apologized for failing to “express, in a clear and definitive way, condemnation of the hateful speech that is all too often directed at WNBA players on social media.” Still, I found her honesty refreshing, or instructive, anyway: Clash is revenue.

McNeil understands “clash” to be rooted in infrastructure, as something systemically encouraged and rewarded. An algorithm sees my interest in women’s basketball and serves me nonstop Zapruder film of a common foul slowed to look as sinister as it can. The world’s dumbest people pay the world’s dumbest man to publicize the world’s dumbest opinions on an unmoderated, increasingly bigoted, increasingly anti-black platform. Vile ideas are floated, artificially, to the top.

Online hate's scope can seem so vast that for one voice to “condemn” it with any effect sounds like a fantasy. The league's statement after the "BAN NAILS" game felt belated, if not futile: “While we welcome a growing fan base, the WNBA will not tolerate racist, derogatory, or threatening comments made about players, teams and anyone affiliated with the league.” I’m not sure if this statement is a success or a failure for the fact that I read it and had no idea where it was aimed. At the fan Clark asked security to address mid-game? At the person who emailed Carrington a racist message threatening her with rape and death? Rather than absolve the league of responsibility, McNeil's point might hint at its power or next steps. The WNBA streams games on Twitter and Facebook. It counts Google among its league “Changemakers.” In a few weeks, it will begin “the WNBA Finals presented by YouTube TV.”

Brennan, a renowned columnist with deep background in Olympic sports but comparably little history covering the WNBA, was at the Fever-Sun playoff series for a book she’s writing on Caitlin Clark. This season, I’ve been grateful for discussions with friends and colleagues who follow the league less closely; their perspective sharpens my own thinking, asks me to consider norms and ideas I take for granted. Distance can be valuable. But I’m often confused by Brennan's read of this story. Here's an excerpt of an interview she did this summer with The Catalyst, a “journal of ideas” from the George W. Bush Institute:

How would you describe Caitlin Clark’s influence on basketball and on how the media covers the game?

The numbers are extraordinary. This year, for the first time ever – and I cannot believe I’m about to say this sentence – the NCAA women’s basketball final had more viewers than the men’s final, 4 million more.

Yet just three years ago, women couldn’t even use the brand “March Madness.” For years, women’s basketball was denigrated, laughed at, joked about. “They can’t play above the rim,” people said, “and they’re just rolling around trying to get the ball on the floor.” All that misogyny, all that sexism. Now compare that language to where we are today. I’m going to give credit for the change to one person: Caitlin Clark.

Where are we today? Engelbert wouldn’t be alone in using Magic-Bird as shorthand for the NBA’s explosion in popularity—by this telling, a frictionless triumph of charisma. The historian Theresa Runstedtler complicates that narrative in her book Black Ball, a study of professional basketball in the ‘70s, the “Dark Ages” from which Magic and Bird are often said to have rescued the NBA. It’s in this era, Runstedtler argues, that black players laid the league’s foundation, popularizing a style smeared as “playground ball” while also agitating for greater economic rights. As they began to make up a greater share (and eventually the majority) of the sport’s labor force, they challenged its white establishment. Basketball became a symbol for a newly integrated America. “The rules of the game had changed, allowing more Black people onto a formerly white playing field,” Runstedtler writes. “And now they were ruining everything.”

That dynamic might be playing in inverse here: as backlash. To a certain kind of white person, extending grievance from outside the realm of basketball, Clark represents the dream of space retaken. Caitlin Clark, the actual human, is incidental to all of this. She has only ever spoken of the WNBA as a community she wanted to join. The push to set her against the power-hungry mean black lesbians both ignores that wish and precludes it. “These people were my idols. I grew up wanting to be like them,” she said at the Fever’s season-ending press conference on Friday morning, part of a longer answer she gave on racist and hateful comments from people she said “aren’t fans” but “trolls.”

The turbulent NBA Runstedtler describes in her book isn’t much older than the WNBA today. Like those players then, WNBA players now are figuring out what sort of league they want to play in. This past Friday, the WNBA players’ union made the unusual decision to call out Brennan by name in a pointed statement, criticizing her for trying to stoke the controversy. The Washington Post's Ben Strauss reported on Wednesday that Connecticut’s DeWanna Bonner confronted Brennan about her question to Carrington later that day. After “nearly two minutes of mostly talking past each other,” Bonner left, and Brennan reportedly told a group of reporters nearby “that something like that wouldn’t happen in the NFL. She asked why the WNBA was so sensitive and told multiple reporters that if anyone had questions about her awareness of the racial dynamics at play, they should read her coverage of former NFL quarterback and activist Colin Kaepernick, among other work stretching back decades.”

That the industry colleagues rushing to Brennan's defense were primarily white and male might speak to that group's tendency to underestimate the cruelty, misogyny, and racism that have long shaped WNBA players' experience, online and offline—or it may just be an artifact of the enduring whiteness and maleness of sports media. “Either the WNBA wants to be treated and covered like other major leagues or not,” one reporter wrote.

What if they don't? It's a compelling possibility, one I've contemplated every time someone tells me it's actually good that Stephen A. Smith has just wrapped up his latest excruciating First Take segment on the WNBA. Maybe the league is ill-served by a press corps that takes women seriously only when they emulate men. Maybe a group of athletes uniquely attuned to the trick of visibility—all its promise, all its threat—would like to set different terms for themselves. The modern woman athlete must be totally accessible to her fans and brand partners, because she makes more for her image than for her work. She must shrug off slights and slurs, because she is a professional athlete, not allowed to be sensitive. She must be totally gracious to everyone who deigns to cover her, because she is a woman and desperate for attention. Right now, those are the rules. But they don’t have to be.