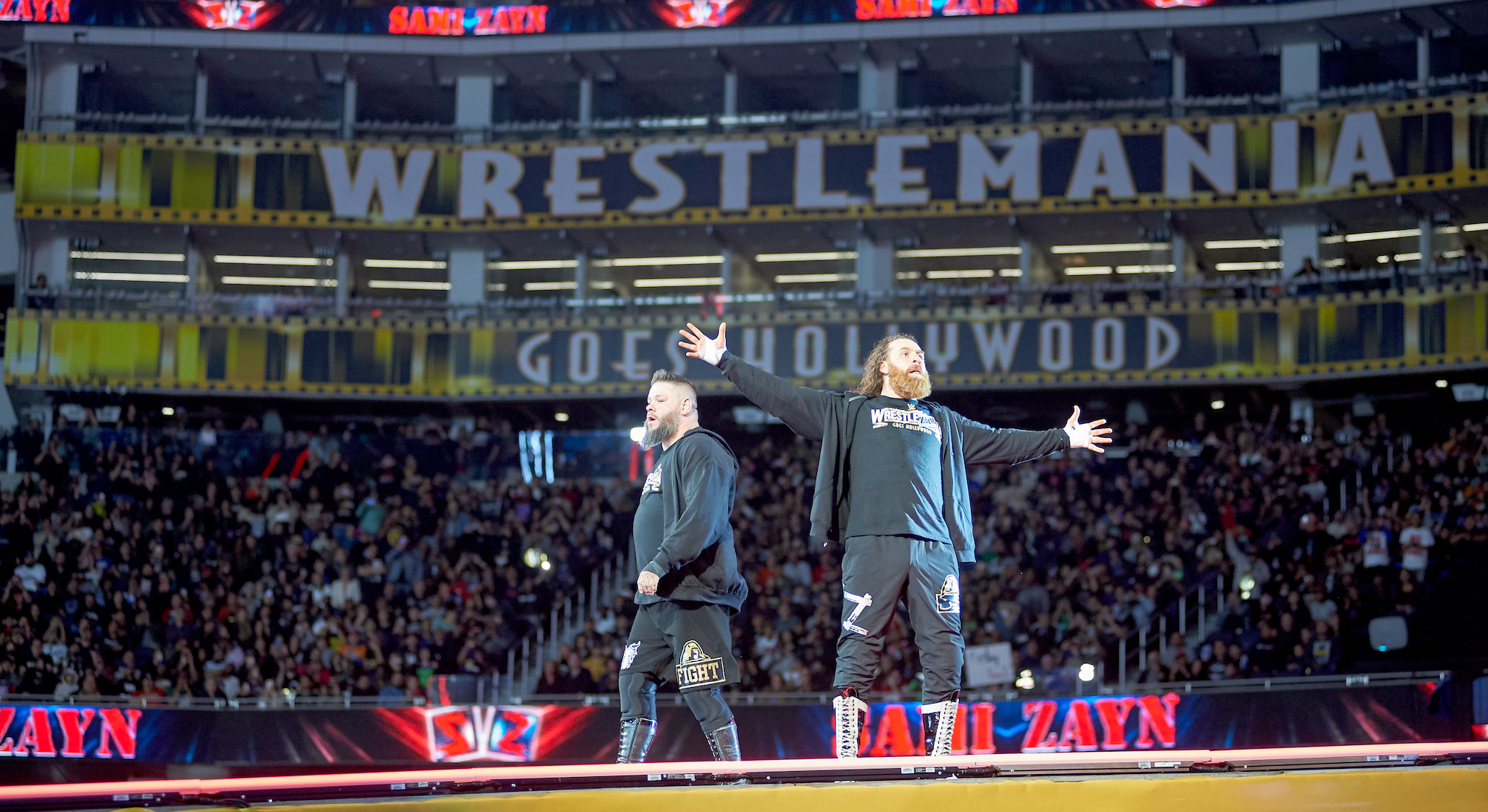

A small moment from the first night of this weekend's WrestleMania that left a mildly unpleasant taste in my mouth was the entrance of Kevin Owens and Sami Zayn in the main event tag match. It wasn't their fault. They were the best part of the whole event.

Ten years ago, at an American Legion building 25 miles away in Reseda, Kevin Steen told El Generico, "I would be nothing without you" as the latter said his goodbye to the indies and signed with WWE. Now, together, they were the centerpiece attraction at a mindbogglingly lucrative supershow. To say Zayn and Owens had come a long way to get to Mania isn't quite right. Their past, and the rare kind of authenticity they project in a company usually allergic to it, is so central to their appeal that it's hard to claim they've put a lot of distance between themselves and their old territory of Pro Wrestling Guerilla. It's more accurate that WrestleMania came a long way to get to Kevin Owens and Sami Zayn.

Anyway, while I was thinking about all of this, WWE's broadcast cut away from their entrance so their announcer, Michael Cole, could do an ad read for TurboTax.

Does the cheapening of the entrance crack the top 1,000 annoying or shitty things this company has done? Of course not. But it did underline where "cool wrestling moments" sits on the hierarchy of priorities in WWE. After so many other piggyback shows this Mania weekend that focused on nothing but wrestling, wrestling wrestling, almost to exhaustion, the bloated product placement and uncanny ad tie-ins at WrestleMania consistently lowered the quality and pacing of the overall experience. There was Rey Mysterio shaking hands with a cereal mascot in the middle of an homage to the late Eddie Guerrero. There were Drew McIntyre and Sheamus doing a hack beverage ad right before a match. It was all Super Bowl–esque, for better in the ways that it reached a scale no other wrestling show can, for worse in the ways that the commercialism overshadowed the thing people actually like.

While its rival AEW had done a stupid gambling tie-in and a few weird ads for other shows in the Warner empire, WWE is really the only wrestling promotion with the desire and the pop-culture cachet to be able to pump a show with this much corporate synergy. The indies can't do it. New Japan isn't doing it. In no other place are the ads this much of the product. And particularly since these former pay-per-views stopped needing to sell themselves individually to viewers now that they're part of a streaming service, and after a Mania that WWE says doubled the previous high-water mark for sponsorship revenue, this is only going to get worse.

Something much bigger than vulgar aesthetics is happening to this company, though. On Monday, in a culmination of the sale process that's dominated the wrestling world for months, megalithic talent agency Endeavor announced that it would be absorbing WWE and spinning it off with UFC into a new company that will look to rule both the fake-fighting and real-fighting markets.

Today, @Endeavor announced it has signed an agreement to form a $21+ billion global live sports and entertainment company made up of @UFC and @WWE. https://t.co/lPrkBmKJXm pic.twitter.com/ZBk95c5exU

— Endeavor (@Endeavor) April 3, 2023

The appeal of WWE to Endeavor is pretty clear. It has a similar money-making structure to UFC in that it combines TV deals, ticket sales, direct-to-viewer sales, sponsorships, Middle Eastern sovereign fund cash, and its own brand licensing all into one big international live events package. It's also appealing because it's physically impossible for WWE to lose money right now, so huge are its deals with parties like Comcast, Fox, and Saudi Arabia. Together, at least in the near future, UFC and WWE are simply too big to fail, and that makes this merger an easy pitch in the boardroom or shareholders' meeting.

Where it doesn't feel so great is in what it is likely to mean for both workers and fans. At the top of the company, this alone is an ugly thing to look at, and I don't just mean the mustache.

Everything in this image is so incredibly weird to see. pic.twitter.com/jbPxwdCZCU

— Chris Vannini (@ChrisVannini) April 3, 2023

The presence of both UFC President Dana White, who escaped any repercussions for hitting his wife on New Year's Eve, and Vince McMahon, who muscled his way back into power despite paying hush money to several women who accused him of sexual misconduct, puts slimy misogyny at the forefront of this new venture. The idea of having either for a boss is chilling.

But even more broadly harmful is the bloodless efficiency with which each promotion has worked to stiff its own employees. In WWE, so-called independent contractor wrestlers have to pay a lot of their own expenses, including health insurance; are nevertheless restricted on how else they can make money; usually don't own the trademark to their own name; can lose their contract with three months' notice no matter how much time is nominally on it; and get paid a small fraction of the revenue share that pro athletes with unions receive. The record profits WWE keeps pulling in are in themselves evidence of this unfairness, and in UFC, the situation is just as bad, as Patrick Redford laid out last year:

The UFC's rank exploitation of its fighters is neither a novel phenomenon nor one confined to a certain strata of fighter. Less than a year before he headlined the UFC 276 PPV, Jared Cannonier flatly declared, "I'm broke, so I need to fight," after a big win. This is an old and well-defined problem, but it's one that gets worse every day as the UFC finds new ways to keep its fighters away from its revenue. The 12-month period spanning Q1 2021 to Q1 2022 was the UFC's most lucrative year of all time, as revenues topped $1 billion. That huge figure translated into huge profit for top brass at the UFC and their holding company Endeavor, thanks largely to the fact that they only pay their fighters a paltry 17.5 percent of revenue. Endeavor likes to brag about their revenues, which naturally leads to questions about why their fighters don't have insurance or any stability. The canned line is that fighter pay has gone up 600 percent since 2005, a statistic that obscures the fact that UFC revenue and profits have leapt 1,700 percent and 6,200 percent respectively in that same time period. When pressed about the yawning discrepancy, UFC execs refused to comment.

That $21 billion valuation quoted by Endeavor on Monday is an eye-popping figure, but that number is so high specifically because workers aren't paid their due and don't enjoy the protections of a union that your typical star athletes and actors take for granted. If Endeavor gets its way, they never will. This is an established giant looking to further extend its reach, and it should be expected to pull every lever possible, from sponsorships to budget cuts, to maximize its return on this investment.

(It's worth noting, in particular, that WWE will be absorbing its share of Endeavor's debt in this merger; its employees will go from working at a company with minimal debt to a company with billions of it. Just take a look at any company, in any industry, that finds itself with with sudden massive debt service; the product becomes rapidly and jarringly worse. It'll suck for employees, too. I've banged this drum before, but there's never been a more vital moment for unionizing.)

The specific future of the biggest pro wrestling company in history remains murky, but it seems like a given that this new era will continue the established rich-guy executive patterns. That means minimizing risk, leaning on corporate and government connections, and doing everything possible to protect the company's ongoing profitability from the actual whims and desires of the customer base. Call it the Marvelization of wrestling: using each performer as interchangeable IP whose personal value is worthless compared to that of the brand. Just as it doesn't really matter who's playing Captain America in the next Avengers movie, because it'll make a billion dollars anyway, it won't matter if next WrestleMania has Kevin Owens and Sami Zayn or Kalvin Ostrich and Sonny Zoom in the main event. If Endeavor succeeds, it'll have created a wrestling and fighting monopoly with no regard for the actual wrestlers and fighters beyond their ability to make some shitty rich guys even richer.