DELHI — The Yamuna River is a lifeline for the people of Delhi. As the second-largest tributary of the Ganges, the Yamuna supplies water to roughly 70 percent of Delhi’s population. It serves another role, too: The Yamuna holds profound spiritual significance, especially for the Hindu community. For centuries, the riverbanks have been sacred sites where Hindus perform solemn funeral rites, offering a final resting place for the ashes of the departed. Alongside the ashes, a myriad of offerings—coins, jewelry, and personal tokens—are also consigned to the flowing waters, a testament to enduring traditions and beliefs in the river's sanctity and its capacity to ferry souls to the afterlife.

Beneath all this religious tradition is a unique economy where the profane meets the sacred. Among the poorest of Delhi's residents are divers, a group of individuals who, driven by necessity, extract their living from the river's depths. Each day, these divers take the plunge into the cold waters of the Yamuna, scouring the riverbed for the valuables cast into the river as part of ritual offerings. They sell what they can find to local merchants, who then sell the items on to their own customers. It's a precarious livelihood, fraught with danger and uncertainty, and it is threatened by a river that is increasingly polluted by industry and destabilized by climate change.

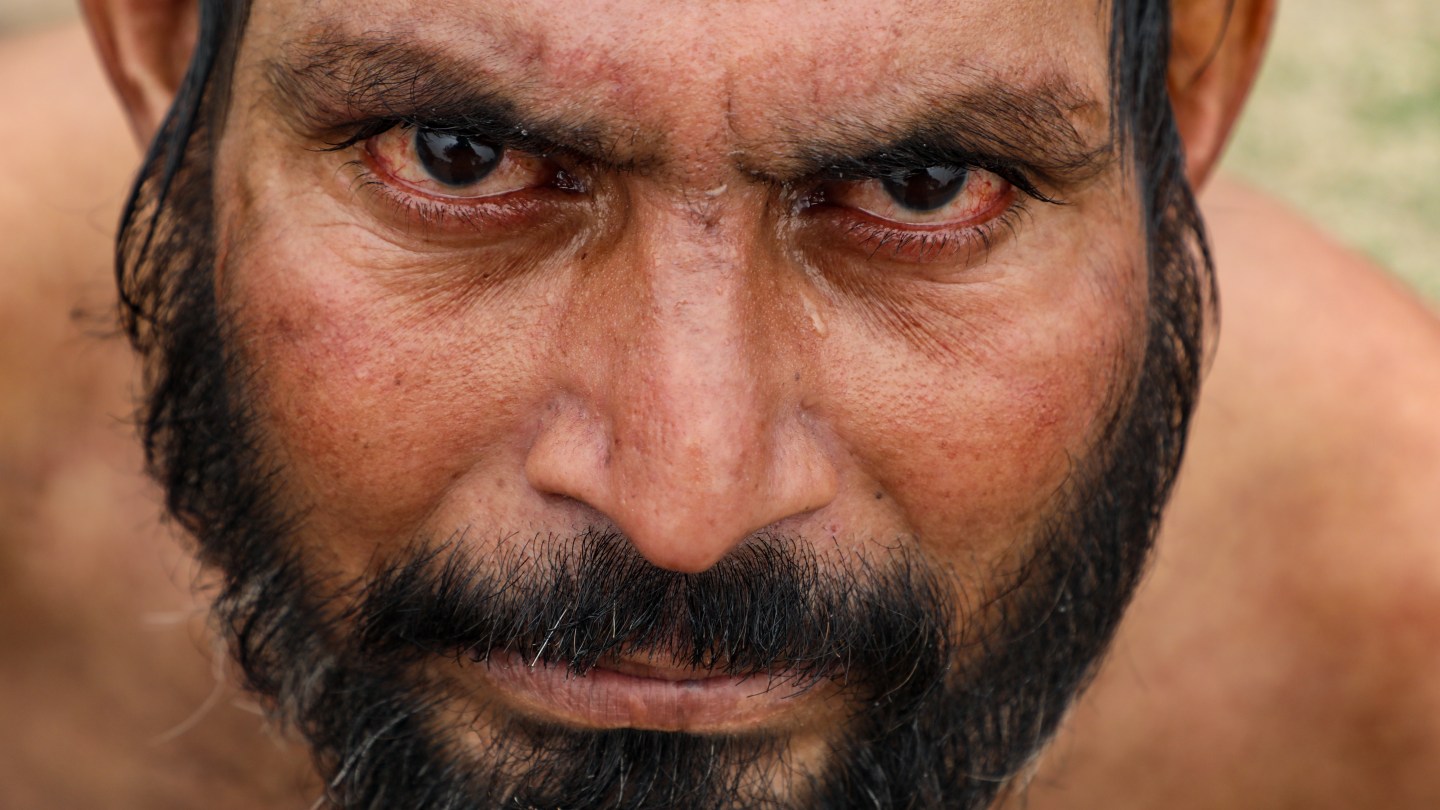

A diver’s day begins in the early morning hours. That is when I meet one, who calls himself “Mental,” on the banks of the Yamuna. I watch as Mental, age 30, immerses himself into the river’s cold waters. He searches for precious metals, iron fillings, coins—anything that could have been deposited into the river bed by devotees engaging in age-old religious practices.

"I was eight when I came to Delhi from Ghaziabad, and have been diving since,” says Mental. “I do this every day, religiously. I have two kids and I dive every day so that they can have a better life and education and move up in the world. Somebody dies and I live because of that. That’s how God has decided it to be."

Diving has become more difficult for Mental over the years, though. “This water was clean during my childhood. I could dive the whole day,” he says. Mental tells me that now he has to be more cautious, due to the sewage, chemical waste, and trash that gets dumped into the Yamuna. He says that skin and breathing issues have become common among the community of divers, but that they continue their practice for lack of better options. “This is our livelihood, and we have nowhere else to go.”

Juman is 18 years old and has been diving since the age of seven, under the tutelage of his uncle Soren, who works as a boatman on the river. “I make $18 to $20 a day,” he says. “That takes care of my expenses, and I give some to my family.” Juman tells me that he only dives in the summer, because the water is too cold in the winter. Even when the water is warm, though, he has to contend with the pollution. He acknowledges that it is bad for his health to continue exposing himself to the toxins in the river, but points out that he doesn’t really have another choice. “I have no education and can’t get a job. Diving is my only way of survival,” he says.

Afroz Alam, 22 years old, is a former diver who found the river’s toxicity too much to bear. “I used to dive since I was 10, but then the river started getting dangerous to dive into,” he says. “Broken glass cut me a few times, and I started having breathing difficulties.” Alam now works as a boatman, ferrying people along the river. His boat also allows him to make additional income through grimmer methods: “Sometimes police take our help in fishing out bodies from the river and pay us $18 a day.”

Shakeel, a 50-year-old diver, has spent much more time in the river than his younger colleagues, and has suffered more greatly. He tells me that the “alarmingly toxic” river has cost him a portion of his eyesight in his left eye, and that doctors have told him he might go blind if he continues diving. “I rarely prefer diving,” he says.

These divers, and their livelihoods, are buckling under the same weight that presses down on all of Delhi’s citizens, who rely on the Yamuna River. The city’s rapid expansion has turned the river into a receptacle for pollution and refuse—factories expel chemicals into its flow, and raw sewage overwhelms the clean water. It is not uncommon to stand on the banks of the Yamuna and see blankets of white, toxic foam smothering the river’s surface.

Some social practices also harm the river—including dumping dead bodies, and other sacred detritus (flowers, remainders of incense, food offerings used in private/domestic rituals, often tied in plastic bags) in the water. In 2021, thousands of dead bodies were found floating in the Yamuna during the country’s deadly second wave of coronavirus. The Ganges and Yamuna rivers pass through some of India’s worst-hit regions; according to news reports, fear of COVID-19 led villagers to dump dead bodies in the river instead of cremating them.

In the stretch between Wazirabad and Okhla, a mere sliver of the Yamuna's extensive journey, lies the epicenter of this ecological catastrophe. According to a committee report submitted by National Green Tribunal in 2018, less than two percent of the river's length is burdened with 76 percent of its pollution load, a stark indicator of the crisis at hand. The deluge of untreated sewage and industrial waste, coupled with the diversion of water at the Hathni Kund barrage for human and agricultural use, has not only robbed the river of its vitality but has magnified the pollution to critical levels.

According to a recent report from Delhi’s Pollution control committee, Delhi's contribution to this dire situation is significant, with an estimated 720 million gallons per day of sewage overwhelming the treatment capabilities of the city's 19 sewage treatment plants, which can only manage 597 million gallons per day. This disparity results in a choked river, its biodiversity and aquatic ecosystems suffocating under the weight of pollutants.

The plight of the Yamuna is further exacerbated by climate change. The severe cold waves that have swept through Delhi in recent years have altered the river's ecosystem.

Initiatives aimed at cleaning the Yamuna have produced limited success. The gap between the urgency of the situation and the response it has received is wide, with environmental advocates like Vimlendu Jha criticizing the sluggish pace and lack of comprehensive action. According to Jha, over 50 percent of Delhi's municipal sewage is not adequately treated before flowing directly into the Yamuna. Although projects under the banner of the National Mission for Clean Ganga and efforts to develop the riverbanks have been set in motion, their impact is yet to be fully realized, hindered by implementation challenges and fiscal constraints.

Near the end of the day, as the sun dipped lower on the horizon and cast a golden hue on the water, Mental's perseverance was rewarded. Amidst the debris of iron filings and copper plates, his fingers brushed against something unexpected: a glimmering diamond nose ring.

With a smile on his face, Mental emerged from the water, his find cradled in his palm. Such a find had the potential to provide for his family for days to come. But the sense of triumph only lingered in the air for so long. As Mental hurried to dress and warm himself against the biting cold, the reality of his situation once again became inescapable. The river, with all its secrets and treasures, can offer respite to divers like Mental, but only briefly.