PARIS — Rafael Nadal has a higher success rate at winning matches at Roland Garros than I do tying my own shoes. I'm more likely to fumble one of my shoestrings than he is to lose three sets on clay to any other tennis player. Going into this year, Nadal had won 112 of 115 matches at the clay-court major. It is not just one of the great feats in tennis, but one of the most consistent performances in any competitive human endeavor. Being that good at something must make it incredibly difficult to stop, as Nadal's almost-38-year-old body was perhaps telling him to do.

So if this really was to be Rafael Nadal’s last time playing at Roland Garros, a tournament he has dominated as utterly as any athlete has any given patch of earth, then there were lots of people who wanted to see him win. His millions of fans would have liked to see him push through a few rounds on Court Philippe-Chatrier before saying goodbye. The French Open, which has a history so entangled with this 14-time champion that in 2021 it erected a statue of him on the grounds—Nadal's dad was seen admiring it this week—would certainly have enjoyed selling out the stadium for a few more matches. The documentary team reportedly following Nadal to chronicle this final phase of his career would've liked some meatier material. There was a lot bound up in the idea of Nadal performing well here, of ending this long-running story on sufficiently beautiful terms.

That's why the identity of his first-round opponent was so outrageous. Various maladies plunged Nadal to the No. 275 rank in the world, which meant he had to enter Roland Garros using a protected ranking, a tool intended to ease transition for players returning from injury or pregnancy. For the first time in Nadal's career, he was playing this tournament unseeded.

Seeding is a form of protection. It buys a player time before they have to confront the most dangerous opponents lurking in the draw; it's a mechanism to ensure richer matchups later in the tournament. But Nadal, without a seed, was exposed to total randomness, which is why gasps rang out at the draw ceremony when his first-round matchup was revealed: Alexander Zverev, the tournament's fourth seed, a very recent winner of a big title in Rome, and a fairly plausible winner of this tournament. If ever there were conclusive proof that these tournaments do not rig the draws, here it is. Nadal would get no opportunity to tune up his game against a soft opponent; Zverev was almost certain to end his career at Roland Garros. He's also a deeply unpleasant co-star for such a match: Zverev is currently in the middle of a trial in Berlin criminal court, appealing a penalty order for allegedly assaulting his former partner. (He does not have to attend the proceedings in person.)

Zverev said that when he was first informed of his first-round opponent, he figured his brother was messing with him. But he also said that he was grateful to have another opportunity to play Nadal. The last time the two faced off here, in the 2022 semifinals, Zverev was playing well enough to topple the great champion, which remains a hypothetical, because in the second set Zverev turned his ankle catastrophically and tore several ligaments, sidelining him for seven months. "I really wanted to play him one more time," he told reporters, "because I didn't want my last memory to be me rolling off in a wheelchair off Philippe-Chatrier." Despite Nadal's relative lack of preparation before the tournament, Zverev said he was preparing as if to play him at his peak. He brought up the 2022 edition, when Nadal had won none of his warm-up tournaments on clay but nevertheless dominated the tournament.

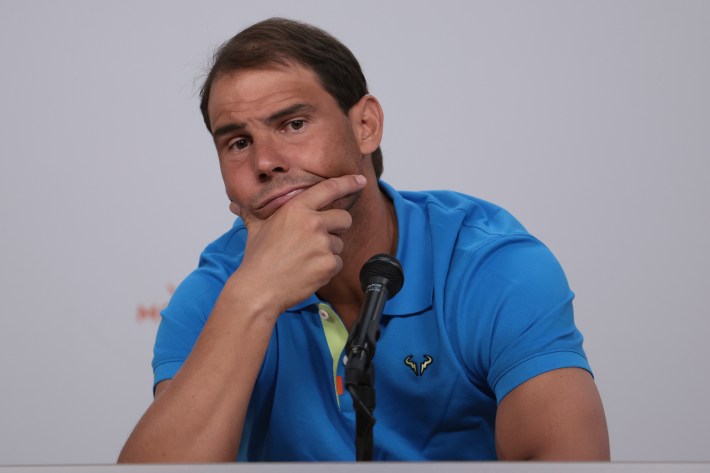

Nadal plays funny games with hope. He isn't the type to close doors conclusively—he would not commit to saying that this was his last French Open—and he likes to update his thinking depending on his present sensations. He speaks a lightly mangled and deeply intuitive English, a broken poetry full of rhetorical questions, bespoke idioms and classic one-offs: "ombelleeble," "what happen-ed," "my famous ass," to pick just a few. His life has been dense and intense enough that he seems to have acquired wisdom at twice the normal rate. And while he is honest about the ravages tennis has inflicted on his body, he always leaves open the possibility that he might restore himself to former glories. Nadal's press conference before the tournament was a masterclass in his usual charms and optimism, and it left the faint and irrational impression that he could survive this first-round test.

It had been a bit of a bizarre year for him. Nadal entered 2024 fresh, playing a warmup tournament for the Australian Open and looking as sharp as he had in years; in his third match, he pulled up lame with a hip issue. He sat out for three months and recovered in time for the clay season, but nothing he did on his favorite surface was terribly convincing. In his last match in Rome, he was routed by the kindly and big-serving world No. 9 Hubert Hurkacz, 6-1, 6-3. He hadn't lost a match that badly on clay since 2003. But suddenly, there he was in this press conference, riffing loosely about the positive feelings he was having on court, the practice sets he’d been playing against other top players. Nadal said that this tournament was magical for him, and was asked if the magic here made his body feel better. "No, unfortunately not," he said with a laugh. "Is not that magic."

On match day, Nadal received an introduction fit for a despot. The announcer Marc Maury did his usual bit, listing out all 14 years he had won the tournament—"deux-mille-cinq, deux-mille-six, deux-mille-sept"—and by the time he arrived at "deux-mille-vingt-deux," the crowd had worked itself into a matrix of staticky white-noise that I faintly remember from Serena Williams’s last matches. It was the loudest part of the whole day.

Since this is my first and likely last instance of seeing Nadal on clay, in person, there are a handful of rituals I am eager to witness, and I check them off my list as they occur. There’s his ritual right after the coin flip: not a walk or jog back to the baseline, but a serrated sprint—a lunging step left, then right, then left, then right, until he's at the back of the court. There’s the way he delicately sweeps the loose clay off the baseline with the bottom of his shoe. Most players can’t be bothered. They are too distracted, too occupied—perhaps by the dread of who they're facing—to perform in-match maintenance on the court surface. During the breaks in the action, Nadal's wedgie removal and water-bottle calibration are the stuff of tennis history. I await his celebratory rite, fresh off a ball he recognizes as a winner a millisecond before the crowd does: a violent half-turn away from the opponent as he uppercuts the air.

The crowd breaks into spontaneous chants of “Ra-fa, Ra-fa, Ra-fa” as he warms up against Zverev. The retractable roof is up, because it's a cold, drizzly day, which means the conditions work against Nadal. He prefers open air, no clouds, the sun baking the clay court a little firmer, so that the ball bounces faster and higher off the court and he has an easier time finishing off points. Because it was chilly enough inside the roof to require a jacket, I knew the court speed would be glacial.

The first point of the match is a medium-length rally that Nadal decides to cut off with an attempted drop shot; it dies at the top of net. Soon after, he hits a double fault. A journalist nearby snickers, as if to deem the whole idea of Nadal's presence at this tournament absurd. The 14-time champion is broken at love. His backhand looks strangely tepid, landing shallow in the court, and the few times he tries to take it down the line, it fizzes meekly off the strings and lands in the middle of the doubles alley. The bread-and-butter stuff is not coming easily. It takes Nadal several games just to execute the simple combo—a serve out wide, followed by a forehand winner into the open space—that has won him thousands of points on this court in his career.

On the other side, Zverev already looks huge and imperious, a kind of baseline pterodactyl. His game combines a powerful and consistent first serve with some powerful and consistent groundstrokes; he gets his free points and makes it miserable for the opponent to get theirs. There were a few moments of brightness for Nadal—a speedy net exchange where he comes out triumphant—but by the end of the first set, Zverev has made 81 percent of his first serves. There's a moment late in the first set when Zverev abruptly turns up the heat on a rally, expecting it to be met in kind, only for everyone in the stadium to realize that Nadal didn't have that same register anymore.

Things warm up in the second set. Nadal fends off a break point and offers a light "Vamos." He holds serve with an ace down the T and rises into an insurgent, airborne fist-pump, and the crowd pops alive, as if remembering the identity of the man in front of them. Back in the day, this kind of excellence would have been ordinary, replicated a dozen times in a single sitting. At a match here in 2017, against a despondent Nikoloz Basilashvili, I watched on TV with grim curiosity as Nadal won nearly 70 percent of points in the match.

On this court Nadal used to delete opponents with a rigor rarely seen in tennis. It was hard to applaud each haymaker when the guy has landed eight in a row on an insensate corpse. Now, these kinds of points are scarce. They have become so precious that common tennis fans like Novak Djokovic, Iga Swiatek, and Carlos Alcaraz have showed up in the seats to watch in person, paying homage to the ultimate clay-court player. I have often felt that Nadal was the ideal player I would design in a vacuum to succeed on clay; my imagination failed to conjure up any potential improvements. Watching him against Zverev, I could definitely imagine a handful. Those old feelings of awe grew more distant by the minute.

There are heady moments in the second set as Nadal goes up a break; the atmosphere grows lively and desperate. Then, while serving for the set, Nadal falls into a 0-40 hole and does not crawl out of it. Watching Nadal hit his signature shots, I have begun to see a ghostly overlay, the 2013 version of that same shot projected over the present-day reality. Peak Nadal would have gotten to that ball not just one step but two steps faster; the down-the-line forehand pass that bonked into the middle of the net post would have instead arced savagely outside Zverev's reach before dipping back into the corner of the court, following that infamous banana curve. It is possible to see the thrilling, crackling outlines of what Nadal once was, and occasionally the ghost and the present slide into serene alignment, before falling out of sync again. A slow and rickety recovery step, a belabored backhand falling a few feet before the service line, and that brief illusion is over. The players go to a second-set tiebreak. Nadal again sees some real chances. The constantly snickering local journalist near me gets up to leave. Was it that hard to imagine that one of the great comeback architects in tennis, playing for the last time at his favorite tournament, could keep this match at least interesting enough to watch? I never want to be so wised-up that the world feels that obvious.

Nadal loses the second set. Some fans in the stands stream toward the exit—apostates in the temple, or people with full bladders, it's hard to say. On the laptop screens around me, journalists begin to assemble ledes, fact-checking their numbers, looking up Robin Soderling on Wikipedia—the only player besides Djokovic to beat Nadal at this tournament—and all I want in that moment is for the match to get complicated enough that all these preemptive paragraphs are scrapped.

It doesn't quite play out that way. Nadal breaks immediately in the third set, but the match had by then assumed a consistent rhythm: As soon as Nadal gets any kind of momentum, Zverev snaps back into form. He breaks back with the single most miraculous shot of the day, a plunging backhand return around the net post that Nadal never had a chance to touch with his strings. The crowd gives it the minimum viable amount of applause and not a clap more.

Zverev wins the match, 6-3, 7-6(5), 6-3. Nadal's lifetime record at Roland Garros is now 112-4, his win rate scandalously dipping below 97 percent. The mood is bleary and confused, the crowd no longer loud or even connected to the action. Immediately after the handshake, there's an odd interview session on the court with the players, effectively drying out any wet eyes in the stadium. Anyone looking for a moment of deep feeling, or closure, is instead left with ambiguity, some of it in Nadal's own mind: He still will not rule out a future return, and reportedly nixed a formal ceremony commemorating his career. Some of the ambiguity is operational: I remain puzzled by the insistence at tennis tournaments to hold stilted question-and-answer sessions in windows of vivid, life-altering emotion. Just hand over the mic and let the players cook. It would be a shame if that was the last time Rafael Nadal was on the clay at Roland Garros. He deserves to go out in a haze of absolute fan delirium.

Even if that was his last time playing in the tournament that has defined his career, he could be back on the same grounds in a few weeks to compete in the Olympics. Nadal was asked in his post-match press conference if he felt ready to play. "I cannot tell you if I will be here or not be here in one month and a half," he said. "Because my body has been a jungle for two years. And you don't know what to expect. I wake up one day and I found a snake biting me. Another day, a tiger. It have been a big fighting with all the things that I went through." Nadal resists a tidy ending. He keeps seeing the flicker of possibility, the shadow of an old feeling, and then he is tempted to tear off the snakes and punch back the tigers all over again.