It's a strange fact that, as baseball has simultaneously gotten smarter at virtually every organizational level and more virtuosic in terms of individual performance, it has not necessarily gotten better. Or maybe it is not that strange, just given that there is something more to the whole of the sport than the sum of its variously optimizable component parts. If it were as simple as pushing every slider and dial further and faster to the right, baseball would have been perfected over the last two decades, and to the extent that anything can be perfected in that way, it has. But we live less with than within the limitations of that approach, and not just as fans—if this was how it worked, all the added productivity we've plowed into our economy might have made us richer, or happier, or at least have given us some more free time. Instead, we just got more productive. The systems perfect themselves around us, everywhere, because they are not really about us, and really not for us.

It's not true, I don't think, that baseball was somehow better when everyone involved understood it less, or understood it more as something mystical and abstruse and less as another problem to solve through the rigorous full-spectrum application of best practices. (It absolutely might have felt better, or I might have just been a kid and so too young to understand how to feel bad yet.) It was still ruled by spiteful rich men and administered by the sort of shabby goons that those kinds of rich men favor, but the fashions have changed, there. It is hard to miss the sort of local flavor and extra dementedness quotient provided by, say, Charlie O. Finley and Billy Martin, or Fred Wilpon and Bobby Valentine, because there wasn't really very much charming about it; it burned itself out as a matter of course, because everyone involved was in some way out-of-control. But as everything about the sport continues to converge on peak optimization, and as everyone involved gradually evolves to assume the shape of an investment banker in a quarter-zip fleece, it is easy to miss the color of the older, dumber, multiply more ragged game.

That game just had a bit more room in it, where the unknown spaces in the map were still illustrated with fanciful dragons. The experience of baseball becoming more and more solved, or quantified, is claustrophobic; the margins close in, the extra stuff is delayered and delayered again, and if what's left is more efficient, it is also by necessity much smaller. In every baseball sense, a team is better off with a shortstop who can both hit and field, although some extraordinary skill at one can balance out a shortcoming in the other. And now, most teams do have shortstops like that. Some of them are 6-foot-8, now, but there is very little room on a roster for a single-tool virtuoso like Rey Ordóñez.

If you saw Rey Ordóñez play shortstop during the parts of nine seasons he spent in the Majors, you know what you are mourning; if you remember how his story was told, you might miss a moment when baseball still talked about prospects in terms of mystery and myth. But to look at it from a baseball perspective, it makes sense. Ordóñez's one tool was his defense, and that tool was a Stradivarius violin; his other tools, from his offense to his makeup, were not tools at all. They were, upon closer examination, expired Lunchables packages. How much you care about this, and how many bites of that jarringly shiny orange cheese you are willing to choke down in order to hear the music that one tool made, is finally a matter of priorities. As a Mets fan in the late 1990's and early '00s, I didn't really have a choice. At some point in the last couple of decades, baseball's executive fetish for optimization made that decision for everyone watching the games. It is odd to sometimes get a pang for the taste of that old stuff, which was not good or good for you, and which was in point of fact just whatever some cynic thought you'd be willing to settle for.

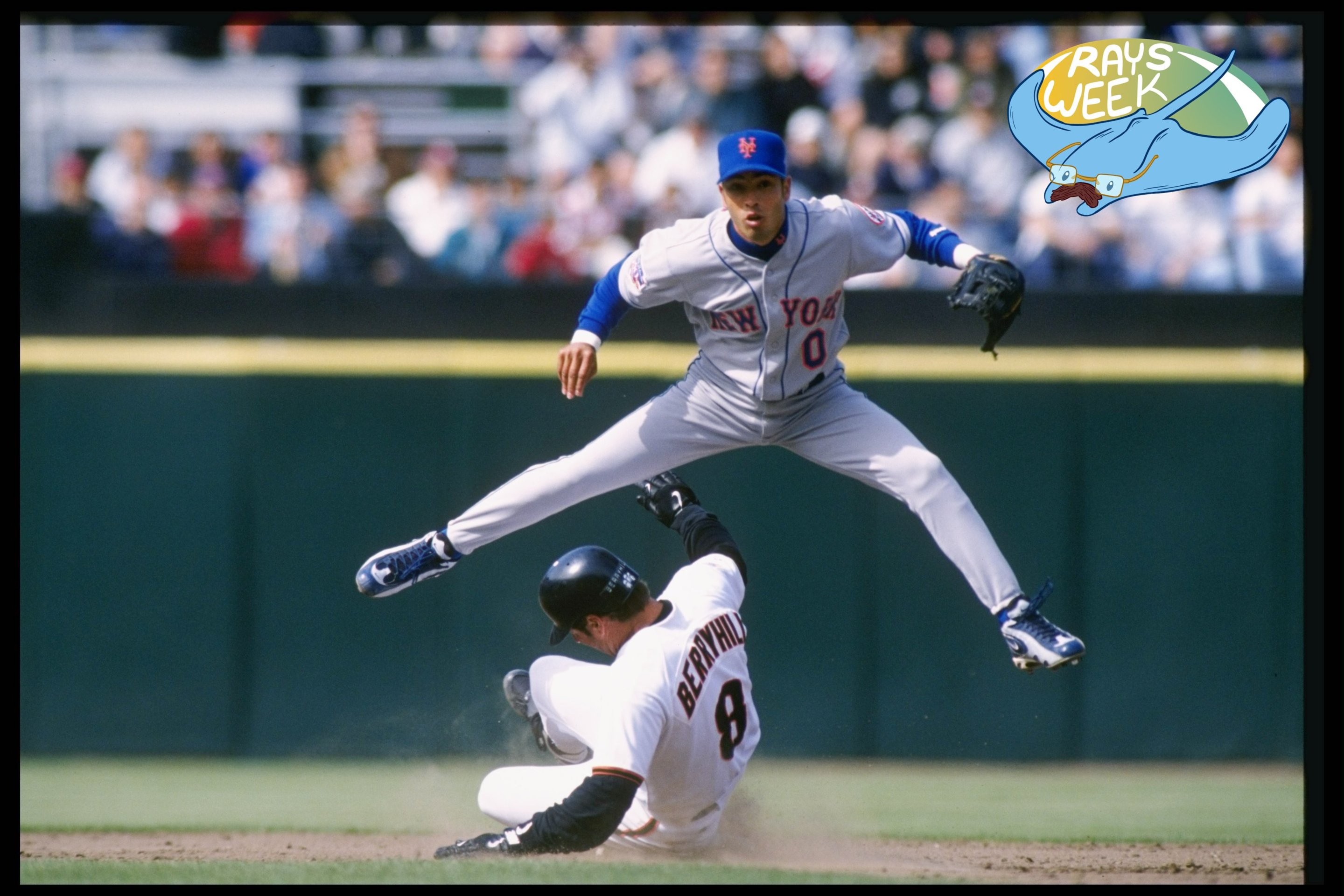

In 2017, at an old job, I wrote about how Ordóñez fit into the evolution of the shortstop position. The fact that Derek Jeter was making his significantly higher rise with the Yankees around the same time meant that I was hardly the first person to make that comparison, but it was striking even then what an antique Ordóñez was, and how much more he had in common with the sort of good-field/no-hit types that had dominated the position for most of baseball's history to that point. That was true only to a point, though, because the good-field part was so extraordinary—Ordóñez was the first shortstop to do a lot of wild things on defense, and is still the only player to have done some of them.

For all the over-the-top stuff about how Ordóñez came to be in the bigs—he defected from his Cuban team during an event in New York State, literally climbing a fence and hopping into his future agent's red Cadillac; 22 teams entered a lottery for his services while the details of his eligibility were worked out—there was nothing excessive about the praise his defense received. People who had been around the game forever attested, over and over, to seeing Ordóñez do things they'd never seen done, and had never really even thought about. "I’ll tell you what’s amazing," Mets third baseman Robin Ventura said of his shortstop. "It’s the sound of Rey’s feet moving after a ball. I can hear his spikes moving through the dirt. It’s a very distinctive sound, like nothing I’ve ever heard before." The offense would come, or it wouldn't; the defense was enough.

The extent to which the offense never came is, in retrospect and also in that context, remarkable. In Ordóñez's best seasons, his OPS was rarely within hailing distance of (to pick another glove-forward Cuban shortstop) Jose Iglesias's worst. He didn't hit for any power, or with any patience, or with any kind of consistent approach to speak of. He fought with his teammates—literally, sometimes, as when Luis Lopez gave him six stitches in 1999—and frustrated his coaches and spoke, annually, about how he had rededicated himself to working harder and smarter before playing more or less as he always had. In 2000, when the Mets went to the World Series, Ordóñez could only watch; he'd broken his arm on F.P. Santangelo's helmet months earlier, on a play at second base. He never really came back, although he kept sort of coming back. In 2003, in 124 plate appearances with the Rays, the offense was briefly if unsustainably there. Ordóñez put up a .316/.328/.487 slash line and hit three homers, tying his career high for a season. It couldn't hold. He got hurt, played one more season, and went to Spring Training with a number of teams that declined to take him north. It is a very prosaic way for a baseball career to end—a bunch of photos in strange uniforms on the wire, pushing the memorable stuff further and further out. Was he ever with the Mariners? The Padres? Really?

The instinct, or anyway my instinct, when it comes to things from the past that are lost and gone forever is to mourn them. There's no reasoning to this, really; the Mets have run many, many more dispiriting and flawed players out there at shortstop since Rey Ordóñez left and it is by now a matter of public record that I'll absolutely keep drinking that garbage. If baseball is not necessarily better for all the work it has done to approach perfection, the players really are better. As a general rule, more players do more things well than they used to. The part I miss, and the part I think I am actually mourning, is not the old idea that a player could be good enough at one thing to make up for any, every other deficiency. There's nothing much to miss, there. It's just another thing people used to believe was the outer boundary of the possible.

What I miss, I think, is the thing that Ventura described—the sense that something different might happen and maybe was happening, something so new that no one even knew what it sounded like yet, let alone what shape it might take in the next moment. In that Vice story, the writer Jason Fry told me what it was like to be at Ordóñez's first home game as a Met, when he made the relay throw against the Cardinals that's embedded above. "A kind of strange murmur/mutter," is what he remembered. "50,000 people make a strange noise when they've devolved into 25,000 pairs devoted to one person asking the other, 'Did he really just do that?'" This is Ordóñez's legacy, and it fits that it is so unquantifiable. It's the awe and excitement of that undefined possibility, the sound of footsteps coming up very quickly, all of it suspended in the moment before it resolves, as it must, into the actual thing it would be.