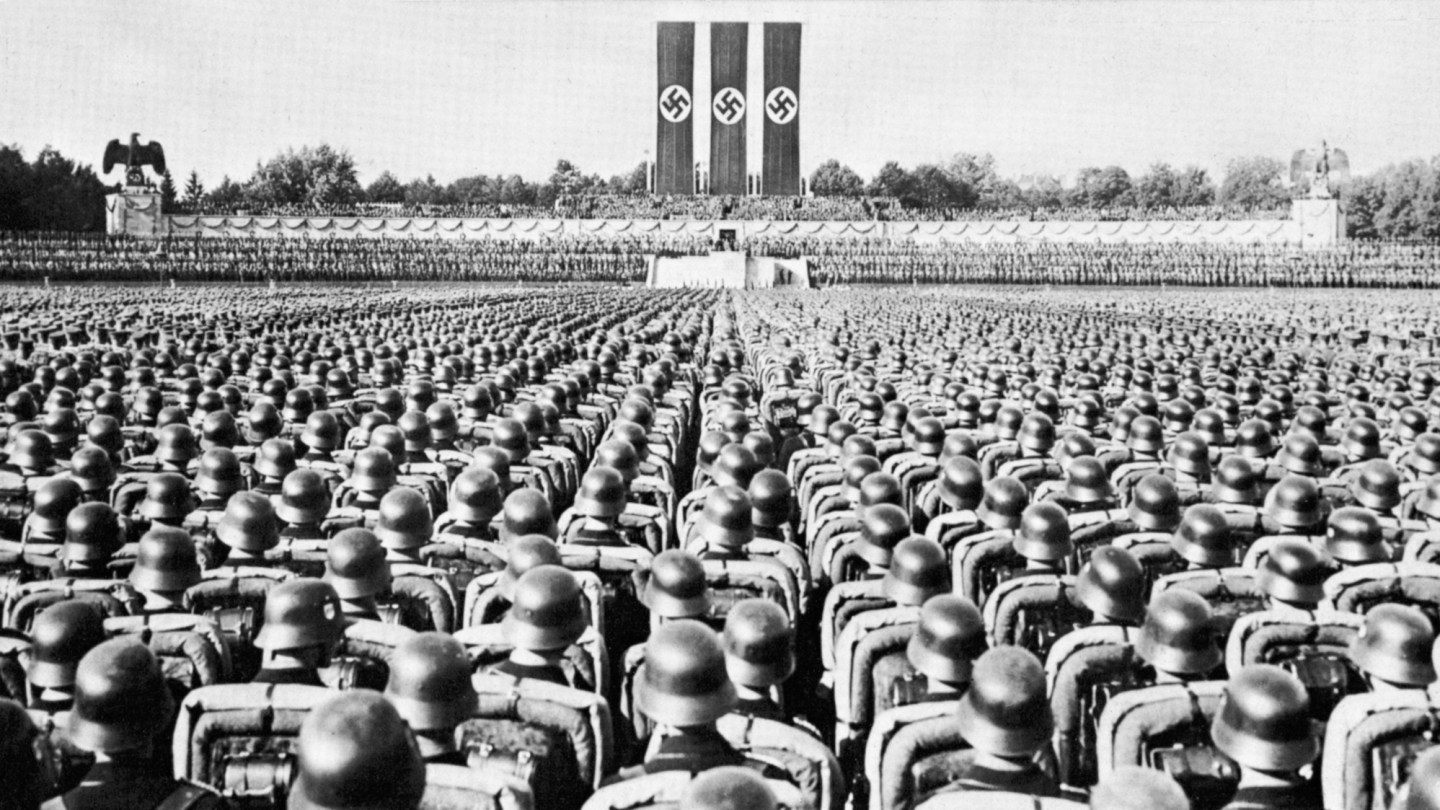

It would have been as absurd as it was triumphant. The great baseball players of the day—even those in the service; especially those in the service—playing baseball on a field that had not long before seen tens of thousands of Nazis parade in lockstep and Adolf Hitler’s oration fan the flames of war. The All-Star Game at the Nazi party rally grounds in Nuremberg. It could have happened.

As the Second World War wound down in Europe, soldiers were looking for a return to something resembling a normal life, with normal activities. In their off hours, even in combat, they’d turned to baseball, an activity that could be therapeutic as well as fun. “I wonder if the folks back home realize the hold baseball has on the men,” said Roscoe “Torchy'' Torrance, a Seattle Rainiers executive serving in combat in the Pacific. “You’d be surprised to see how quickly a man snaps out of it after going through an invasion. Baseball and other sports take his mind off what he has gone through.”

Mike Todd was not a baseball man. His interests could be found more on Broadway than at the Polo Grounds. But the 36-year-old theater impresario had made a career out of finding out what people wanted, and giving it to them.

“GIs want American entertainment,” he said in early June of 1945, a month after V-E Day. “And there isn’t anything more American than the All-Star Game. We will have a couple of carloads of hot dogs, plenty of peanuts, and we’ll have the game right here where Hitler used to strut.”

In hindsight, it seems like a fait accompli that 1945 dawned with the end of World War II in sight. But the year began with fierce fighting in Northern Europe as Germany mounted its last counteroffensive, the Battle of the Bulge, still one of the bloodiest fights in American history. In the Pacific, the Americans had retaken the Philippines at the end of 1944, but were still plagued by Japanese aerial attacks on their bases and aircraft carriers. American forces were preparing to invade an island that was used as an air base for Japanese forces, a spit of land called Iwo Jima, as a prelude to an invasion of Okinawa, and then perhaps mainland Japan itself.

Back at home rationing and travel restrictions were in place, to the extent that MLB’s All-Star Game had been canceled for the year—the first time that had happened during the war—and there was real doubt that the World Series could be played that fall.

During World War I, Secretary of War Newton D. Baker (a Cleveland native who a decade later would become part-owner of the local club) had issued the “Work Or Fight” order, requiring that every able-bodied male either join the military or work in an industry supporting the war effort; this led to shortened major-league seasons in 1918 and 1919. When the United States entered World War II, however, President Franklin Roosevelt issued what’s now called the “Green Light Letter,” saying that baseball was valuable for national morale and should continue, even as many of its players went off to war. But as 1945 dawned and the war dragged on, FDR asked Congress to consider similar “Work or Fight” legislation.

Baseball was in a dire spot, in more ways than one. MLB was without a commissioner, at a time when the commissioner was the most powerful person in the sport. Kenesaw Mountain Landis had been appointed to the position in 1920 and given near-dictatorial powers, enough so that his death in November 1944 created a vacuum in decision-making. In lieu of a commissioner, National League President Ford Frick and his opposite number in the American League, Will Harridge, met with the Office of Defense Transportation, which oversaw civilian travel during the war.

(At the time, Frick was one of the candidates to succeed Landis as commissioner. But owners, looking for an outsider with political connections—potentially to stave off another Work or Fight rule—hired U.S. Senator A.B. “Happy” Chandler instead. He didn’t serve out the length of his initial contract, and after he was pushed out in 1951, Frick succeeded him.)

The parties reached a compromise. Baseball could continue, but rosters would be trimmed to 22 players and travel would be severely limited. The All-Star Game, inaugurated a dozen years earlier but already an institution, would not be held that year at Fenway Park as scheduled. Instead, there would be a series of interleague cross-town and cross-state exhibitions. There was even consideration of canceling the World Series, which would save an estimated 750,000 passenger miles.

But the tide turned in Europe. The German offensive failed in the Battle of the Bulge. In March, Allied troops crossed the Rhine River into Germany. The following month, Italian partisans captured and executed the deposed dictator Benito Mussolini. Two days later, Adolf Hitler killed himself in Berlin. His successor as Fuhrer, Admiral Karl Dönitz, surrendered unconditionally to the Allies.

And Mike Todd visited Germany. On his way back, he told a United Press correspondent in London, “The war is just beginning for show business.”

There’s a uniquely American archetype of someone who’s not quite a con artist, but gets close enough that the distinction blurs. Fact is, Americans love tall-tale tellers, and having your ambition outstrip your actual achievements isn’t necessarily a character flaw—but you have to deliver often enough to reassure us you’re not a straight-up liar.

That was the story of Mike Todd, whom Time Magazine said “would pass out salted nuts at his own hanging if he owned the beer concession.” Born Avrom Hirsch Goldbogen in 1909 in Minneapolis, he was the youngest of nine children of Polish immigrants. His nickname, mimicking his inability to say the German word for coat, was anglicized to Todd; he formally adopted it as his surname after the 1931 death of his father, an Orthodox Rabbi. In 1918, the family moved to Chicago, when Todd’s father was appointed to a synagogue there. Young Mike started a floating craps game at his school.

By the time he was 13, through nothing but gumption and reading, Todd had passed a test to become the youngest pharmacist’s assistant in Illinois. He started a construction and real estate company when he was 16 (among his building projects were retrofitting movie sets in Hollywood with soundproofing at the dawn of the talkie era), and had made and lost his first million dollars by the time he was 20.

He branched off into entertainment, writing radio scripts and promoting a flame dance at the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago, in which a girl dressed as a moth would gradually have parts of her costume singed off, an irresistible combination of sex and danger; indeed, some models had to be treated for burns. He arrived in New York, his trademark green suits in tow, to produce Broadway shows, and after two flops, became the talk of the town with Hot Mikado and its all-black cast, which he not only produced on Broadway, but made part of the World’s Fair in 1939. He also produced Naked Genius, a play written by Gypsy Rose Lee.

Now an established success, Todd sought more worlds to conquer, and headed to Europe in 1945 to work with special services as a civilian consultant (The New York Times said he had the “assimilated rank” of brigadier general). He was one of the first Americans into Berlin after Germany’s formal surrender, and saw the potential for the massive Nazi parade grounds at Nuremberg as a venue for entertaining GIs with shows and sporting events.

When Hitler came to power in 1933, he declared Nuremberg—historically a seat of power of German kings and the Holy Roman Empire—the host for Nazi Party rallies. Hitler’s architect Albert Speer designed a monumental complex with a parade ground and a variety of exhibition halls. Speer’s 400,000-seat German Stadium was planned but never built. There was the 37,000-seat Municipal Stadium already on site, though, mostly used for Hitler Youth activities but perfect for baseball.

The enormous rallies shown in Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will were shot in Nuremberg. “Just think of it,” Todd said. “These guys can sit in the sun and see the best ballplayers in the world right where the Krauts used to stamp around shouting.”

Todd claimed the military had signed off on his plan. Now he had to work on a bureaucracy even more intractable: Major League Baseball. Happy Chandler had been elected commissioner by owners at their meeting in April, but he would remain in the Senate until November. He seemed aghast at transporting baseball’s biggest stars by plane during a war. Todd’s biography quoted Chandler as saying, “What if the plane crashes? No more baseball!”

The New York Times noted that when players went on USO tours the previous winter, it required weeks of planning beforehand. “It would seem to me to be manifestly impossible,” Branch Rickey told the paper.

In his own memoir, Todd’s son and namesake said the deal fell apart over immunizations; they would not be waived for ballplayers coming over from the United States who might not have gotten them.

But the idea wouldn’t die. At the end of June, a United Press report said that Frank McCormick, the University of Minnesota athletic director serving as director of athletics in the European Theater, had returned to Washington to lobby for the All-Star Game, and the Sporting News in July still declared, “The C-54s are ready and waiting” to bring the ballplayers to Europe. But the interleague exhibitions were played and the second half of the season resumed. By this time, the World Series was no longer in doubt.

Eventually, baseball did come to Nuremberg’s Municipal Stadium—renamed Victory Stadium by the conquering allies, and which, several major renovations later, exists to this day and is home to second-tier soccer club FC Nürnberg—just not the All-Star Game.

A massive athletics program was set up for suddenly idle soldiers in the European Theater of Operations. (A similar program was set up in the Pacific Theater following V-J Day.) The ETO baseball season culminated in a five-game “World Series” between the champions of the “leagues” of teams formed from units in Germany and those stationed in France.

The series opened in Nuremberg, with Ewell Blackwell—a side-armed fireballer who would be nicknamed “The Whip” in his major-league career—leading the Third Army team, stationed in Germany, to a win in the opener. The team stationed in France, led by future Hall of Famer Leon Day, won the second game, and the series moved to France. The teams split two games in Reims, and returned to Nuremberg for the deciding game. The French side, which happened to be the only integrated one, won.

By the end of the ETO World Series, soldiers were looking to return home. Mike Todd was looking west.

As the 1950s approached, TV was becoming inescapable—and movies were paying the cost. Weekly cinema attendance peaked during the war at more than 85 million on average, and started to decline steadily. (Minor league baseball faced a similar problem, after attendance swelled to its high-water mark of 448 teams in 59 leagues in 1949.)

Many Hollywood studios thought the best thing to do was to make movies even bigger, to highlight the contrast between them and television. And Todd—whose fortune was made a generation earlier in part on changing movie technology—was determined to do it again.

Todd initially invested in Cinerama, a unique widescreen moviemaking process. Three 35mm cameras would film a scene, and the picture would be shown by three synchronized projectors on a proprietary concave screen. Eventually, Todd sold his interest in Cinerama and struck out on his own, coming up with Todd-AO, which would use one 70mm camera for a new wide-screen format. The first movie in Todd-AO was Oklahoma!, which Todd had turned down on Broadway a decade earlier. (It may be apocryphal, but Todd supposedly rejected it with “No girls, no gags, no chance.”)

Todd then sold his interest in Todd-AO, which still exists today as a post-production company, to fund what would be his biggest project to date: the 1956 film version of Around the World in 80 Days. The stars of the movie are David Niven, Cantinflas (who received top billing in his native Mexico and other Spanish-speaking countries), Robert Newton, and a pleasant but miscast Shirley MacLaine as an Indian princess, but the movie is at least as notable for popularizing the concept of cameo roles. More than 40 famous actors appeared in bit parts: Charles Boyer was a balloonist; Buster Keaton was a train conductor; Frank Sinatra played piano in a saloon. The movie is regarded today as the worst Best Picture Winner, but it truly is a spectacle, and it remained in theaters for three years.

After Around the World in 80 Days proved to be a smash hit, the world seemed to be Todd’s oyster. He was linked to every major project out there. He was going to enlist the help of the Yugoslavian army to make War and Peace. He would bankroll Laurence Olivier in Macbeth. Todd himself was going to be the subject of a biography by sportswriter-turned-screenwriter Art Cohn, tentatively titled The First Nine Lives of Michael Todd.

And he’d married Elizabeth Taylor, one of the most beautiful and famous women in Hollywood, buying her a 29-carat ring, he said, because 30 would have been vulgar. Walter Winchell said Todd “had won an empire and married Cleopatra.” (Taylor later called Todd and Richard Burton, her actual Cleopatra costar, the two great loves of her life.)

Todd was even ribbed in absentia at the Baseball Writers’ Association of America annual dinner in January 1958. He was the main character in a skit, racing around the world in 80 days to find a new baseball team for New York after the Dodgers and Giants left.

He was flying back east that March for a dinner in his honor at the Friars Club, where he’d be presented with the “Showman of the Year” award. Elizabeth Taylor stayed home with a cold. Todd’s private plane, the Liz, left Burbank on March 21, 1958. A steady rain was falling and the plane was overloaded and icy. In turbulence, the plane climbed to 13,000 feet, higher than was recommended for those conditions. All these were factors in the plane’s crash in New Mexico, killing the four people aboard: the pilot and co-pilot, Todd, and Cohn, his friend and biographer. Todd was 48. Cohn's book, near completion at the time, was released in 1959, slightly retitled The Nine Lives of Michael Todd.

“In a way," Winchell wrote, "Mike Todd’s life was the greatest show he produced.”