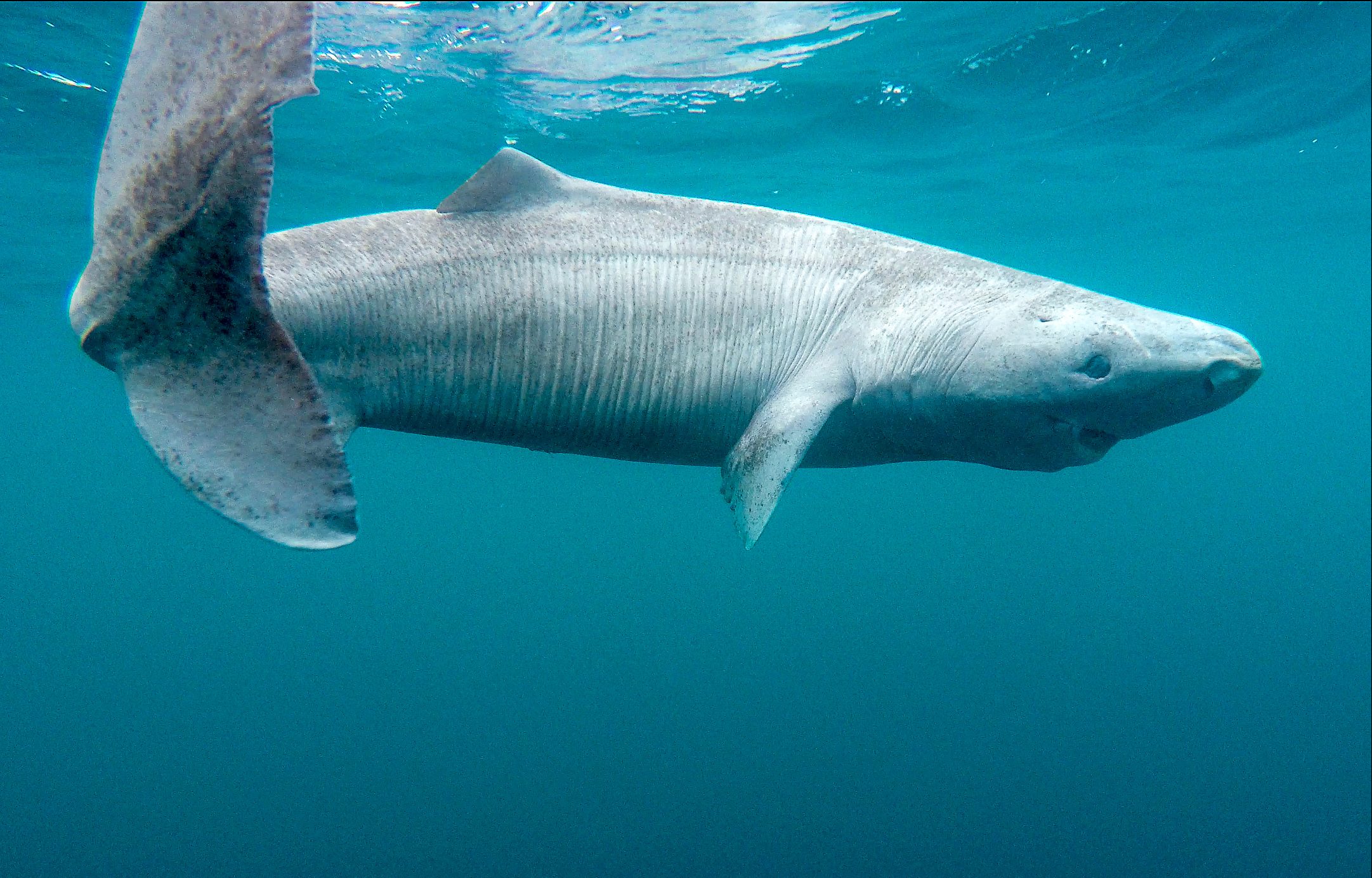

Greenland sharks are behemoths in size and longevity; they can grow up to 24 feet long and live at least 250 years, perhaps up to 500. But the sharks are famous for one other biological quirk: Almost all of them are nearly blind. The sharks are not born that way but are hosts to an inch-long parasitic copepod, a kind of crustacean. A single female copepod Ommatokoita elongata, which looks a bit like a graduation tassel, will dig into a Greenland shark's cornea. There, able to swing freely, the copepod feasts on the shark's cornea and conjunctiva, clouding the eye. As a result, the shark is capable only of detecting light and rough images or nothing at all for the rest of their long, long life.

Plucking out the eye parasites of a Greenland shark can be oddly satisfying. "It feels like you're pulling a grape off the vine," said Eric Ste-Marie, a graduate student at the University of Windsor in Ontario. "That exact sensation." As a part of his research tagging Greenland sharks in the Canadian Arctic, Ste-Marie collects their eye parasites for genetic work. Although removing the parasites may offer the sharks some relief, it does not repair their vision, and more might soon take their place. But the copepods do not significantly affect the survival of Greenland sharks. They are almost a rite of passage for the sharks—a small trade-off for centuries of life.

Scientists know precious little about what other parasites may dwell on Greenland sharks, which swim in deep waters and are extremely hard to find. In research surveys, Ste-Marie has to fish for the sharks with drum lines. "We'll just wait a couple hours and then we basically pull up the line and hope there's a shark on it," he said. "Often there isn't one."

In 2018, Ste-Marie was sampling Greenland sharks in Nunavut. He was there to study their behavior, not their parasites. But as he and colleagues were taking samples and measurements from the underside of one particular nine-foot-long female shark, they noticed something unusual. "We spotted what looked like a burgundy-looking rose petal sticking out of the shark's cloaca," Ste-Marie said, referencing the shark's hole, essentially a multipurpose portal for feces, urine, sperm, and eggs. Bravely, Ste-Marie reached into the shark's cloaca to pull the thing out. "It looked almost like a wine cork covered in these mustardy root things," he said. "I was like, ooh, that's pretty nasty!" No one knew what the thing was, so they dealt with it the way researchers deal with anything mysterious in the field: "Stick it in a vial and put it in the freezer for later," Ste-Marie said.

Two years later, scrolling through Twitter, Ste-Marie saw a photo of eerily similar burgundy petals attached to a lantern shark. Ste-Marie ran to the freezer, dug out the sample, and realized the strange petal was in fact the parasitic barnacle Anelasma squalicola. He contacted Henrik Glenner, a marine biologist at the University of Bergen in Norway and expert on these barnacles. Ste-Marie, Glenner, and colleagues report this observation in a paper published last month in the Journal of Fish Biology.

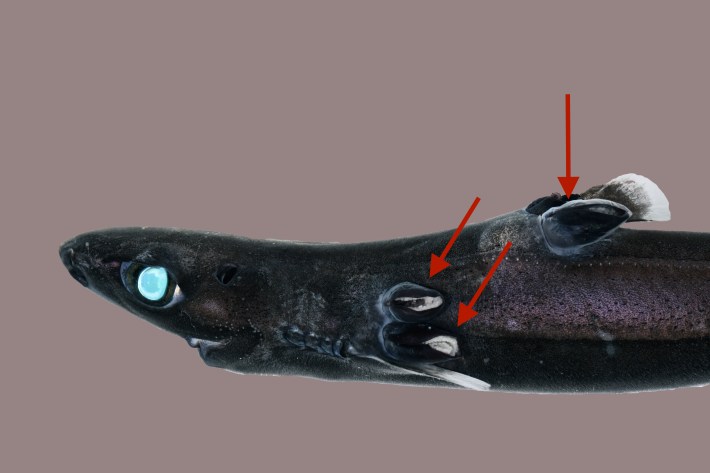

"It was a big surprise to find this," Glenner said. Anelasma barnacles mostly live on the velvet-belly lantern shark, a deep-sea shark about as long as a rolling pin with a bioluminescent belly. The barnacles have been found on a few other shark species, but never on a shark as big as a Greenland. Most barnacles are filter feeders, but Anelasma is no ordinary barnacle. Instead, it attaches to a shark, burrows into the skin, and then sprouts a root-like system to draw nutrition directly from the shark's flesh. Shark skin ripples with dermal denticles, or tooth-shaped plaques, that make it difficult for any parasite to attach to or pierce. But Anelasma digs into less ironclad parts of the shark's skin, such as the dorsal or pectoral fins, the eyes or the mouth, Glenner said. "Sometimes you'll actually find it in the eyes. It's really gross," he added.

Even compared to other sharks, a Greenland shark has particularly impenetrable and abrasive skin, featuring unusually some of the biggest dermal denticles of any shark. So it is no random misfortune that the Anelasma wound up inside the Greenland shark's cloaca, but rather a moment of serendipity (at least for the barnacle). "It's a bit softer, the skin around there," Ste-Marie said. In Glenner's eyes, a cloaca is a perfect home for a barnacle. "When you sit there, it's very protected," he said. Previous studies on lantern sharks suggest the Anelasma barnacles may hinder the shark's ability to reproduce, as parasitized sharks had smaller gonads. But a single barnacle on a nine-foot Greenland shark would possibly have a more diluted effect, the researchers suggest.

To Glenner, perhaps the biggest surprise was the sheer size of the single Anelasma plucked from the cloaca. The barnacle was large—longer than a safety pin—which would suggest it was sexually mature. But all prior evidence suggested Anelasma barnacles, which are hermaphrodites, only become sexually mature alongside a partner. So the big barnacles are always found in couples. "In a few occasions, you find only one solitary barnacle and then they are always extremely small," Glenner said. "It seems that they are waiting, waiting, waiting for a partner to arrive, and then when it arrives they can grow together." When Glenner sampled the solitary barnacle, he found no evidence of eggs, suggesting the creature, which ironically lived its whole life inside a cloaca, never had the opportunity to mate.

With only one example in an understudied population of sharks, it is difficult to know how common this pairing of parasite and host may be. But Glenner suspects Anelasma might lurk in many more sharks. "They might have escaped our attention simply because because nobody has been looking for this," he said. "And maybe if they find it, I mean, it looks a bit gross." In Glenner's years of research, digging around for parasitic barnacles in museum specimens and living fish, he knows parasites are much more common than people might want to think. "I've been a barnacle guy for many, many years," he added.

No one knows how long Anelasma barnacles live, or how long they might live while burrowed into a host that could live for hundreds of years. Glenner is particularly interested in learning about the evolution of Anelasma, and how the barnacles manage to live in waters all around the world. "Here we have a living animal that is between two completely different ways of life, it has just given up filter feeding and has now turned into something completely different," Glenner said.

Ste-Marie also experiences a kind of awe when encountering the similarly mysterious, much-larger subject of his research. "It's kind of weird to be looking something like that in the eye and being like, 'wow,'" Ste-Marie said. "Not every day you get to interact with something that's been around for that long." Although it's currently impossible to ascertain the age of a Greenland shark without harming the animal, Ste-Marie estimates the nine-foot-long female he encountered has "gotta have been around for a while," he said. And somewhere in the Canadian Arctic, she is swimming slowly with a lighter, emptier cloaca.