The historian met the Copt in Jerusalem in 1956. TATTOOS WITH COLOUR read the sign on the door, but the historian walked in to find nothing but coffins. Jacob Razzouk greeted him and, noticing the man’s confusion, told him that the tattooing supplies were in the back corner of his carpentry shop. Tattooing pilgrims was an honor, but it didn’t keep the lights on, so Razzouk built boxes to ease the path for the same men and women his ancestors had given safe passage to while on this mortal coil. Tattooing for Coptic Christians, Jacob explained, was not merely ornamental but a ritual born out of survival. It is said to have started in neighboring Egypt, the Copt homeland, during the Islamic revolution of the seventh century—a way of marking Christians by authorities which eventually evolved into a symbol of resistance and rite of safe passage into churches and the medieval equivalents of safehouses.

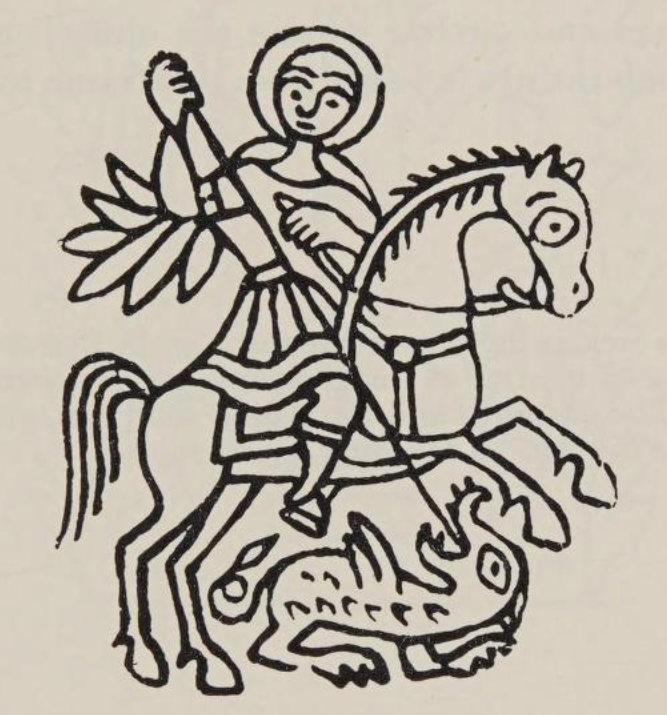

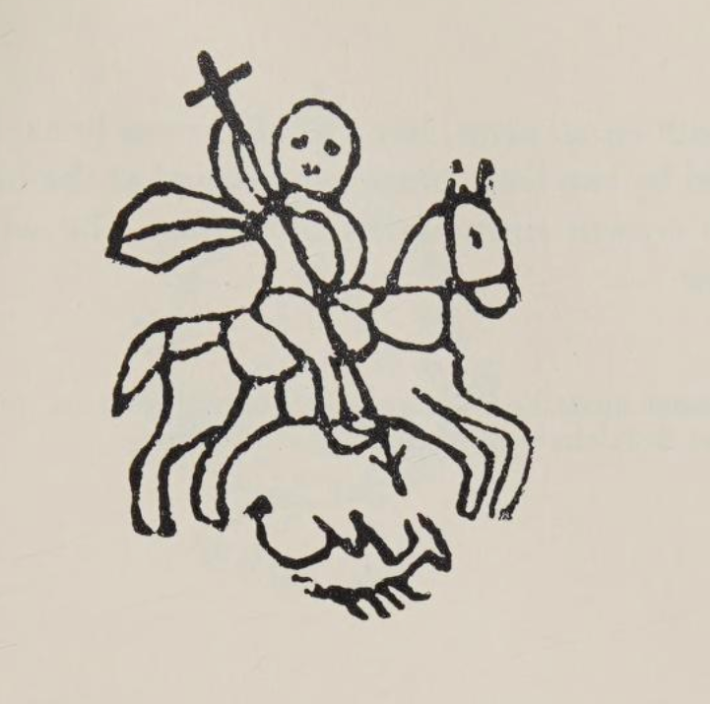

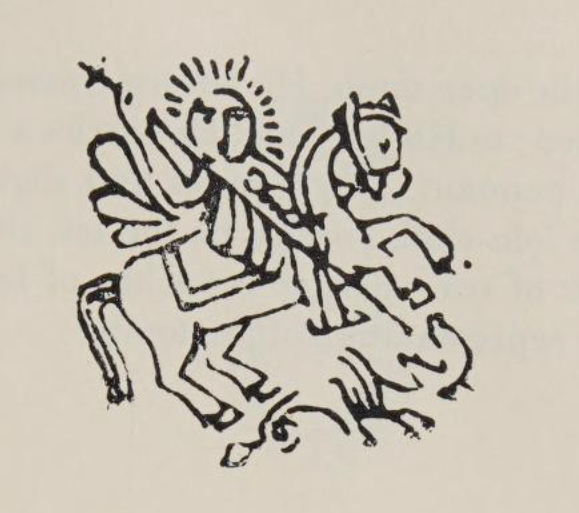

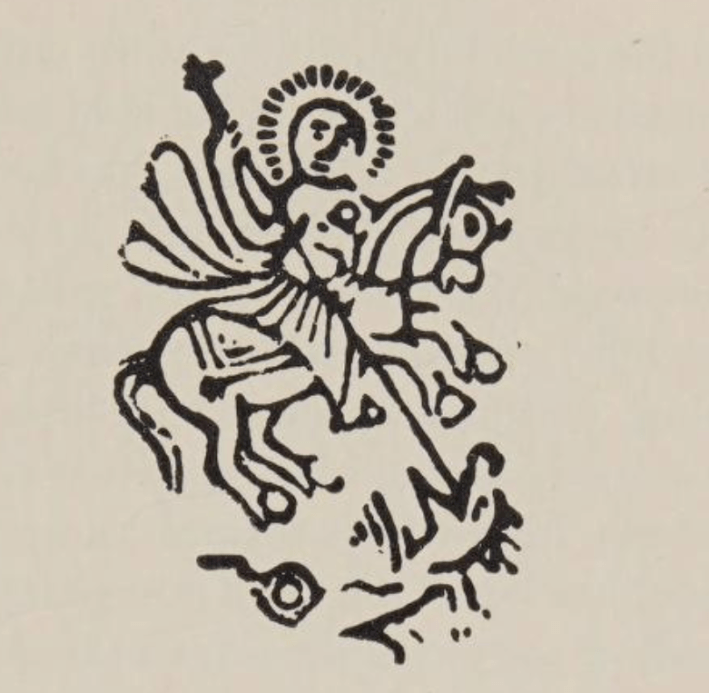

Razzouk was one of two tattooers in Jerusalem at the time, the other an Armenian, but Razzouk’s shop in the Old City had something special: blocks of olivewood, centuries old, carved with stamps of Coptic symbols, some of the motifs predating even Christianity itself. Like every religion, Christianity built itself with the iconography at hand, and some images have popped up again and again as long as humans have been alive and drawing. The ancient and the modern: Jacob was the first of the Razzouk family to introduce the electric needle to the area, allowing him to tattoo exponentially more pilgrims and local residents alike. The locals would often get tattooed on specific occasions throughout the year, while the pilgrims tended to arrive during the Easter season.

For those from Armenia, or Ethiopia, or Syria, or any number of countries that had seen centuries of violence at the hands of one empire or another, the tattoos were a culmination of a lifelong devotion to something that their ancestors died for. For pilgrims from the West, like the Anglican historian, the tattoos were souvenirs—proof that they’d seen the Holy Land. This tradition started long before the Englishman arrived, when his forerunners would ride in on horseback spattered with the blood of Saracens or Jews or, as in more than one crusade, other Christians that the Catholic Church wasn’t overly fond of. Christians like the Copts, those descendants of pre-Islamist Egypt that follow what is among the oldest Christian denominations. In the present day, Catholics return from the Holy Land inked with the iconography of the very people they had tried to subjugate.

Still, the Razzouks tattooed them all the same, whether souvenir collectors or pilgrims or emperors. In the 1930s, Jacob the carpenter had tattooed Haile Selassie of Ethiopia, the “Lion of Judah,” the last ruler of the Solomonic dynasty, which claimed descent from the biblical king. Always cognizant of history, Haile Selassie specifically requested his tattoo from the family who had been providing them for centuries. It was what Razzouks did, and what Jacob’s father did, and his grandfather. In fact, the Razzouks have been tattooing in North Africa and Palestine consecutively for more than 500 years, their olivewood stamps a Rosetta stone to the type of living history scholars dream about. Unfortunately, unlike the surviving written word of the conquering historians, much of the history of some of the oldest Christian denominations on Earth is only contained in the drawn folklore that has roots dating to the years not long after Jesus walked these same streets. Those symbols survive etched onto pieces of wood in a tattoo shop.

The English historian, John Carswell, went on to publish his account of Jacob Razzouk and the olivewood stamps in Coptic Tattoo Designs, published in 1958. Carswell did a fine job of placing the symbols in the context of how Copts used them traditionally, but he failed to interrogate why the individual faiths differ in their approach to and general acceptance of tattooing. Western Christians, historically speaking, tend to forget that they were the last ones to the party.

Occasionally, a young Palestinian Muslim going through a rebellious phase would wander into the shop, as they still do, and more often than not they chose Saint George slaying the dragon, an essential (and rather on-the-nose) allegorical foundation of Western Christianity, and English empire in particular. But that's not what Saint George means to Muslims. They know him by another name. He is al-Khidr, The Green One, a companion of Moses and an eternal servant of God who took on different forms through history to slay the evils of tyranny.

So much of the clash between East and West, and between Eastern and Western thought, can be told through the variegated history of this particular bit of iconography. Something superficially straightforward can look very different through the eye of the needle.

As the Crusaders rode through the Holy Land swinging swords and hammers at every dark-skinned person they could find, one has to wonder if, while laying on the ground before the lights went out, their victims happened to notice that they were staring back at a version of al-Khidr, who, since at least the 12th century, has also been the symbol of brutal conquest.

One suggestive version of the image is still discreetly tattooed—outside of the Holy Land—on Westerners who are often already peppered with more obvious symbols of their racial supremacist beliefs: that of the central image on The Order of Saint Michael and Saint George, a British chivalric order established to reward those holding commands in the empire’s Mediterranean territories—a bowling trophy for rich boys in colonized states. The iconography is fascinating in the way antiquated horrors usually are, borrowing the traditional image of Saint George standing astride a slain dragon, but instead depicting a sword-wielding Michael the Archangel conquering Satan. But while Satan has a dragon’s green scales and a dragon’s green wings, his head is that of a dark-skinned man. No one ever accused the British of subtlety.

But before the English stole Saint George for their own imperial purposes, the legend of al-Khidr had a far different meaning in places like Palestine, Egypt, and Ethiopia. There’s little consensus around anything about the real George’s life, other than a high degree of likelihood that he was persecuted by the Roman Emperor Diocletian around the turn of the fourth century. What survives otherwise is folklore and legend, and the legends in the East paint a far different portrait than do the narratives of the West. Instead of a man who fought against the Roman Empire in favor of advancing Christianity, Saint George (or al-Khidr) is a wise man who couldn’t be killed by the Emperor, despite three seemingly successful attempts on his life. In Islam, al-Khidr is a merchant opposed to the worship of false gods, revered in the faith as a sort of equivalent of John the Baptist, a forerunner of the true God’s message. For the Druze, al-Khidr is John the Baptist.

In Western Christianity, al-Khidr or Saint George has also been identified with the Green Knight of Arthurian legend; for that we may have yet another religion to thank, the major yet forgotten faith of Manichaeism.

Born in Iran before spreading into China, Manichaeism was a complex work of a third-century prophet named Mani that melded Buddhism, Christianity, Cosmology, and aspects of Zoroastrianism. Manichaeism may best be thought of as a slightly more dogmatic version of the modern Unitarian Universalist movement, or the Baha'i Faith, an attempt by Mani to create a unified global religion by syncretizing the beliefs and major figures of existing faiths. There is an Incantation of Saint George in a Manichaen text that clearly supports the legend of him as a faithful resurrector of life–rather than a violent evangelizer and martyr. Chaucer studies of the past decade and a half have increasingly suggested that the tale of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight likely made its way to England from traders in the East and along the Silk Road, where the Islamic and Oriental Orthodox depictions of the The Green One and Saint George, respectively, became syncretized, adapted and revised into Middle English literature.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is one of the most adapted and widely known of the Camelot tales, in which a supernatural challenger arrives at the Round Table daring one of the knights to strike him. Gawain, the eager knight, accepts the challenge, beheading the Green Knight and watching in horror as it stands up unphased and exits, reminding him of the terms of their challenge: in one year’s time, the Green Knight would return the favor and behead Sir Gawain. The most common retelling involves Gawain resisting seductions and eventually finding out the whole thing was folly, and the lessons learned are far from obvious. Given the context of an introduction from the East, there’s an obvious interpretation of the tale derived directly from the dualist versions of Christianity that were prominent at the time and evident in Manichean faiths, with the Green Knight representative of God the Father, a separate entity from Gawain, His most worthy son to be sacrificed for the sake of the kingdom. Or perhaps, given Islam’s legends of al-Khidr, the Green Knight may be thought of as the wise companion to Gawain’s Moses, imparting lessons about giving one’s faith over to the unknown.

Given more than 1,500 years of Saint George being adapted, absorbed, syncretized, and spun off, and the “evil” he slays standing in for very different notions of real-world nemeses, it should be small wonder that he remains a popular request in Razzouk’s shop. He can represent as many things as there are customers who choose him, even if sometimes those representations can seem to be in direct conflict.

In the 17th century, there was a back and forth between English thinkers about the true historical origin of Saint George. Edward Gibbon put forth that the real Saint George was the martyred bishop George of Cappadocia, an argument summarily dismissed by historians because the timeline couldn’t have matched up. But what of the possibility that Gibbon, a noted deployer of satire and a polemical anti-religious writer, wasn’t being literal? What if Gibbon was intentionally drawing a parallel between the insidious Saint George of the English empire and George of Cappadocia, a tyrant who so violently imposed his Christian faith on the locals that they quite literally tore him to pieces?

It’s in this context that it makes sense for the icon of Saint George to have survived the Crusades and the modern-era geopolitical dissection of the Near East to still be revered among the ethnic groups that were killed in his name, to still end up on the skin of those who have lived here since time immemorial. Saint George remains a popular tattoo among Americans and Brits, especially military men, but al-Khidr is among the oldest symbols of persistence for its own sake: an endless quest for knowledge in the face of suffering, and safe passage for those who seek it. Good tattooers know the power of symbols.

Eventually Jacob Razzouk’s son, Anton, took over the family business, operating it primarily out of the same corner of what was now a souvenir shop in Jerusalem. Handling the steady flow of pilgrims during Easter season was no problem, but for larger groups (usually pilgrims on an organized trip) the shop could get a bit tight. So, on occasion, he’d travel to their hotel to do the work. The advantages of tattooing in a hotel are the space and time afforded. The disadvantage is that hotels in Jerusalem tend to have uneven lighting situations. As Anton aged and his eye and hand started to falter, the tattooing sessions became more difficult.

One day, a group of Ethiopian pilgrims waited patiently as Anton set up his supplies in their hotel, but at the last minute he turned to his son, Wassim, and told him that he couldn’t do the tattoos because of the lighting. Something with his glasses, or his eyes; the details grow hazy with time but Wassim knows vision was the excuse his father used, though he suspects he may have also been shoving the young man out to sea a bit. To that point, Wassim had only been tattooing oranges and grapefruits, never someone’s skin.

Wassim Razzouk never wanted the job, he says. He was fascinated by the process and the designs but turned off by the lack of hygiene. Old-school tattooing being what it was, gloves were often optional, cigarettes were often present, and the less said about sterilization the better. His father would pester him to apprentice but it simply wasn’t what Wassim pictured for himself. In the early 2000s, he read an interview with his father where Anton expressed his deep sadness at what appeared to be the end of the family’s centuries of tattooing, and Wassim decided to look up his last name on the nascent World Wide Web. He began reading the articles and books, by tattooers and pilgrims, who raved about the name Razzouk and the traditions. Something finally clicked, and he told his father he would apprentice.

That’s how Wassim ended up tattooing his first pilgrims in the dim light of the hotel, tears in some of their eyes as he finished Coptic Crosses, or Saint George, or the Resurrection. “You can see on the faces how important it is to people,” he says in his shop today, occasionally interrupted by potential customers who he makes sure to greet cheerfully and thank for stopping by. He says it’s Americans more than any other group who appreciate the ancient olivewood stamps, primarily because they are flabbergasted by the physical stamps being much older than the United States itself. These Americans tend to be Christian tourists to Israel, often flown in with church groups that can afford to send pilgrimages on a near-quarterly basis, and never miss an Easter season. Some collect tattoos each time they return, peppering their forearm or bicep or chest. Schedules fill up quickly during holy weeks.

The Orthodox pilgrims are less concerned with the history of the stamps and more interested in the tradition behind them, he says. For example, when Armenian pilgrim groups visit, almost every member of the group will sit for a tattoo. “Even the grandmas,” Wassim laughs. For Armenians, “it’s a very important part of the pilgrimage. They know their ancestors have done it because they’ve seen it on their arms.”

Jews in Israel don’t tend to get tattooed, given the traditions of Rabbinic Judaism and the prohibition implicit in Leviticus. That story, though, gets more complicated with the Beta Israel, the Ethiopian Jews isolated from mainstream Judaism for a thousand years and believed by some to represent the lost Tribe of Dan.

The Beta Israel’s Jewishness was only officially recognized by Israel in the mid 1970s, decades after some of the community made the difficult journey to Jerusalem, though were denied citizenship because they had been cut off from the diaspora and therefore practiced very little of what is recognizably Rabbinic Judaism. Many Beta Israel did not shun tattoos, nor did they consider the Coptic crosses on their foreheads to be Christian symbols. It was a beautification mark to them, like their henna patterns on hands and wrists indicating some form of historical intersection with Indian culture. However, once they arrived in Israel, many of the Beta Israel were ostracized for their body art, a sort of scarlet letter of their lack of Rabbinic tradition. Despite coming from destitute conditions, some were forced to spend what amounted to their life savings to go through the painful procedure of having their tattoos removed.

The occasional Muslim still comes into Wassim’s shop for a tattoo they can easily obscure under clothing, and it’s usually still Saint George slaying the dragon. The folklore in the region today holds Saint George as a symbol of safe passage for persecuted faiths in general, not necessarily just Christians. In Palestine, in the town of al-Khader, stands the Monastery of Saint George, in the same area where George was said to have been imprisoned. There, every May, Palestinian Christians and Muslims alike celebrate the Feast of Saint George. Muslims guard the entrance to the church as Christians march in unison. There are meals shared under the olive trees, and lambs sacrificed and shared with each other and God. The tradition is said to date to the Byzantine era.

Wassim has added another layer to the legacy of Razzouk Tattoo, relocating slightly but now able to run a full-time shop; no more coffins or gift-shop bric-a-brac. His sons Nizar and Anton are apprenticing, preparing to become the 28th generation of Razzouks to carry on the tradition.

Wassim is perhaps the most talented of the recent Razzouks, now the third generation using an electric needle and the first to start creating more elaborate designs and offer portrait-style tattooing and artistic renderings beyond the stamps. The iconography remains relatively limited, but that’s a matter of demand rather than supply; pilgrims seeking tattoos in the Holy Land tend to have a bit of a one-track mind.

“I am tattooing the Resurrection more lately,” Wassim says about recent customers. “I’m not sure what that means and haven’t thought much about it, you know? But that is something that I have noticed more, that people are asking for the Resurrection.”

It’s not just in the Holy Land where the iconography can be limited. Crosses, third eyes, Saint George, lions, swastikas, resurrections: throughout the world, the same body markings end up recurring over generations not because of a lack of imagination, but because of something that predates literacy, something that speaks to people in their language no matter what their holy men say. In the Near East, where the emblems originated before the West rebranded them as fearsome symbols of supremacy, the original meanings are still preserved in the old tongues. There are still churches and rock walls where the symbols all mingle, and modern-day hides that have been carved, as a reminder of the undying instinct to transcend the world rather than conquer it.