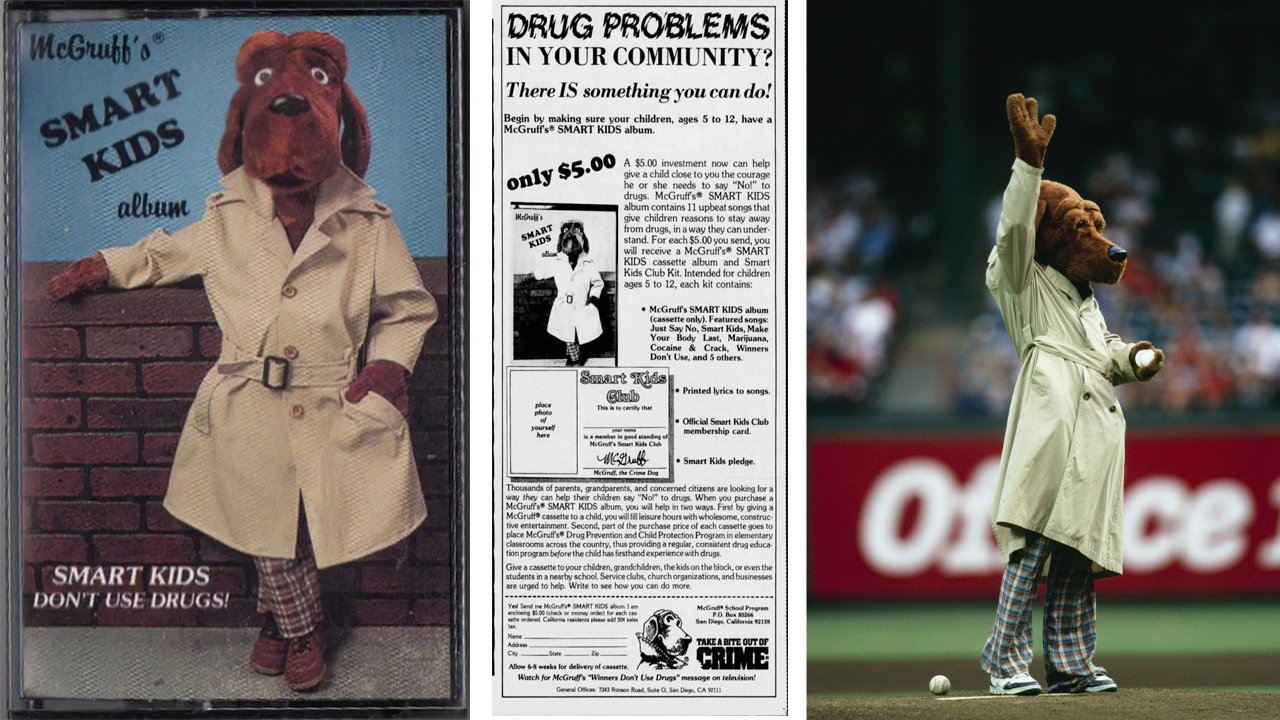

The advertisement ran in the July 12, 1987 edition of Parade Magazine. The Newspapers.com database shows that 61 newspapers carried it that day, but considering that Parade's circulation was around 20 million at the time, there were no doubt many more. It ran in papers big and small: Indiana’s Vincennes Sun-Commercial but also The Washington Post, Boston Globe, and New York’s Daily News. The ad, which was certainly donated space, promised a solution to a pressing problem. It told readers: “DRUG PROBLEMS IN YOUR COMMUNITY? There IS something you can do!”

The answer to the problems was, naturally, a $5 cassette of anti-drug songs featuring McGruff the Crime Dog on lead vocals. The ad—which used the Shatter font, previously used by AC/DC and Manic Panic hair dye, at the top—said the five bucks was an “investment that can help give a child close to you the courage he or she needs to say ‘No!’ to drugs.”

The idea for McGruff began in the 1970s out of the Ad Council, a company created by advertising professionals with a mission to share propaganda during World War II. Franklin Roosevelt asked the council to continue its work after the war ended, and the era of public service announcements began. The Ad Council has created some memorable characters, like Smokey Bear, and receives donated ad space from television stations, newspapers and magazines, billboard owners and other places where people advertise. The most recent figures I can find say the Ad Council gets $1.8 billion in free ad space every year, which is about 20 percent of the entire donated advertising market.

As Wendy Melillo writes in How McGruff and the Crying Indian Changed America: A History of Iconic Ad Council Campaigns, McGruff was created in the late 1970s as an anti-crime advocate. It all started (doesn’t it always) with a man angry with non-carceral approaches to combat crime. Carl Loeb, a businessman, quit his gig at the National Council on Crime and Delinquency and founded the similarly-named National Crime Prevention Council. Kicking in $250,000 of his own money, he got the U.S. Justice Department to give $750,000 more to create some sort of anti-crime spokesperson.

Ad man Jack Keil came up with the slogan “Take a bite out of crime,” and originally drew a Snoopy-looking dog wearing a hat. Other rejected ideas included, per Melillo, a wimpy-looking mongrel who became a wonder dog, an aggressive-looking deputy dog, a golden retriever “Sarge” dog and a J. Edgar Hoover bulldog, complete with a cop’s hat and badge. Eventually, they decided on a dog version of Columbo—though the cigar was dropped before the character debuted in 1980.

Melillo claims that the character worked. “In 1984, a Justice Department crime survey found that burglaries and theft had hit their lowest level in the twelve-year history of the survey,” she writes. The Justice Department spent $900,000 for a report that noted “the character may well approach the general popularity of Smokey Bear as a campaign symbol.” McGruff quickly moved beyond simply munching on misdemeanors. The “McGruff House” campaign encouraged homeowners to put a photo of McGruff in their windows as a way to signal to kids it was a safe place. (I don’t know if McGruff homeowners were vetted in any way.) McGruff even guested on a Very Special Episode of Webster. After that McGruff-led drop in property crimes, the dog needed a bigger target! Inevitably, the answer was drugs.

By the mid-1980s, the U.S. had three parties leading the war on drugs: Nancy Reagan, the police, and advertising executives. McGruff’s 28-minute drug album was part of a concerted plan. As the ad that ran in 1987 describes it: “First, by giving a McGruff cassette to a child, you will fill leisure hours with wholesome, constructive entertainment. Second, part of the purchase price of each cassette goes to place McGruff's Drug Prevention and Child Protection Program in elementary classrooms around the country, thus providing a regular, consistent drug education program before the child has firsthand experience with drugs.”

This was a popular idea at the time: Teach young kids a lot about drugs and how bad they are, and maybe you might succeed in preventing them from ever doing them. This infamous tactic did not really work, with some studies showing programs like DARE actually increased drug use among teens. My favorite of these was 1990’s Cartoon All-Star to the Rescue, where all the Saturday morning cartoon stars teamed up to prevent some kid from doing drugs. This was a legit event to me at 7 years old—it aired on nearly every station, per Dan Baum’s Smoke and Mirrors: The War on Drugs and the Politics of Failure, and the only way to avoid it was to watch C-SPAN or American Movie Classics. In retrospect, I cannot believe it took so long for movie and TV executives to turn the whole media landscape into a series of crossovers and extended universes. (The Wikipedia page for the event used to say that Jim Davis did not want Garfield in this special; I do not know how accurate this was, but I want to believe.)

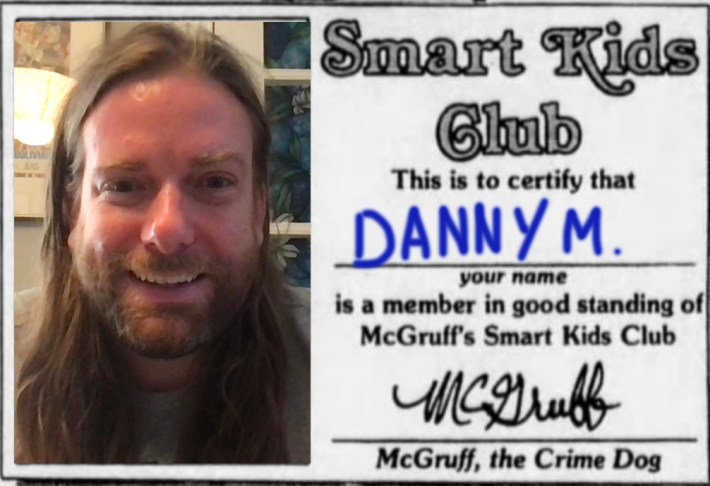

Anyway, the McGruff album: I actually own it. As someone who was interested in drug policy even when I was a teetotaling high school student, I own a lot of drug ephemera. I have several copies of Cartoon All-Stars to the Rescue. I have dozens of books about drugs. And I bought this tape off eBay years back. I couldn’t find it when I went looking for it yesterday, but I know I've heard it before. One track on the album went viral on Twitter yesterday when a users named @bloodberry_tart posted it.

i can’t stop listening to this McGruff the Crime Dog song about the dangers of inhalants that sounds like New Order pic.twitter.com/zPs9hEfojK

— Berry 🍓🍰🖤 (@bloodberry_tart) July 14, 2021

McGruff was voiced by Jack Keil himself. And instead of getting a singer to do the actual singing—Garfield’s singing voice at the time was Lou Rawls—it appears Keil did all the singing here himself. @bloodberry_tart says this track sounds like New Order, and I agree, but I also think the intro sounds like Eddie Murphy’s “Party All The Time.” This album’s 1984 release date predates Murphy’s hit song, so perhaps Eddie Murphy and producer Rick James copied McGruff. We can't rule it out.

Weird Al Yankovic has a type of song called a “style parody,” which virtually no one else has been able to pull off even half as well. Yankovic is a talented performer, and his uncanny gift for creating catchy, not-annoying songs in bar none the worst genre of music there is, the song parody, has won him deserved fame. His style parodies are often even better. Yankovic’s style parodies attempt to mimic the style of a particular genre or musician. His 1986 song “Dare to Be Stupid” sounds so much like Devo that Mark Mothersbaugh said he hates him for it.

Well, it turns out this McGruff album is a whole series of style parodies. In the comments of @bloodberry_tart’s tweet, someone pointed out the McGruff song titled “Alcohol.”

unbelievable pic.twitter.com/t0RvTi0PGU

— Don Quikzotic (@swskomal) July 14, 2021

Yes, this is basically a style parody of Steely Dan, only with an anthropomorphic dog singing instead of Donald Fagen. The whole album is like this! The songs kinda bop!

I can’t find any data on how many people bought this cassette, or how popular it was, or if kids hate McGruff's nephew, Scruff McGruff, as much as they hate Scrappy-Doo. But the cassette was promoted for a long time. It has a first copyright date of 1984. In 1990, the Arizona Republic reported on a “Just Say No” party at a local elementary school:

More than 70 members of the Knoles Knights Just Say No Club sang songs from the Officer McGruff Drug Prevention album, including “Smart Kids,” “I'll Say No,” “Make Your Body Last” and “I’m Glad I'm Me.”

Laugh if you will—and I am, very much so—but this kind of shit worked. Not as intended, really—it didn’t work to keep people off drugs—but it worked in terms of convincing a swath of the public that drugs are bad, and that the people who use them are bad, and that the people who sell them are bad. We’ve known for years that the War on Drugs is a massive and brutal failure that has produced mostly negative outcomes. But we can’t let it go. Baum, in his 1996 book, called it “the War on Drugs switched to auto-pilot.” This is what and how it has been for about 30 years.

One drug McGruff doesn’t mention is opiates. Uppers were considered a much larger problem in the 1980s and 1990s, with mass heroin use a thing of the past. That is no longer the case. Yesterday, the government released data that 93,000 people died of drug overdoses last year. People say kind words about this tragedy, but primarily it seems to be a fact of American life. Legalization is not discussed among politicians. Supervised injection sites are shot down by courts and neighbors. The narcs have even admitted they can’t stop anything; Pennsylvania’s attorney general told the Philadelphia Inquirer he considers it a success when he manages to move drug dealers to another corner.

Yet we persist. Is it McGruff’s fault the public feels this way? If we can credit him for the burglary drop in the early 1980s, I don’t see why we can’t blame him for this. Still, much great art has problematic backstories. This album still slaps. Maybe if I listen to it a few more times, I’ll become convinced that users really are losers.

Correction: Originally, this post said the Ad Council’s $1.8 billion in free yearly ad space was 20 percent of the advertising market. Obviously… it is not. It’s 20 percent of the donated ad market. My apologies.