I understand music in more or less the same way that dogs do, and possibly as effectively. There are aspects where I probably have a slight edge (I understand the words, and know that what I am hearing is "a song") and others where you have to favor pretty much any spaniel (attentiveness). I know what I like, and generally know what I am hearing, but also music is a language I do not really speak despite the many hours I have spent listening to it. I just nod along, mostly. This ignorance has, if anything, heightened my appreciation. I do not know how a song is made, really, and I can't even imagine where the best ones come from. The things I've read on this topic don't really help, or more to the point don't diminish the extent to which all of my favorite songs have always hit me as magic tricks. Someone "comes up with" some guitar line or drum fill or whatever, in practice or in a dream or otherwise in the moment, and that is just the explanation—that something I cannot access came to someone I do not know through a process that neither of us can quite explain.

So it means something extra to me when people who can speak this language describe the experience of encountering some new and more elevated form of it. Robert Forster, of the great Australian band The Go-Betweens, described the experience of hearing the band Television's 1977 album Marquee Moon in a story for The Guardian. "Pacing my bedroom in excitement, sitting down at intervals to absorb the music’s overwhelming beauty, I knew I could never write songs as textured and intricate as the band’s singer-songwriter Tom Verlaine, who also happened to be a virtuoso guitarist," Forster wrote. "But I was inspired."

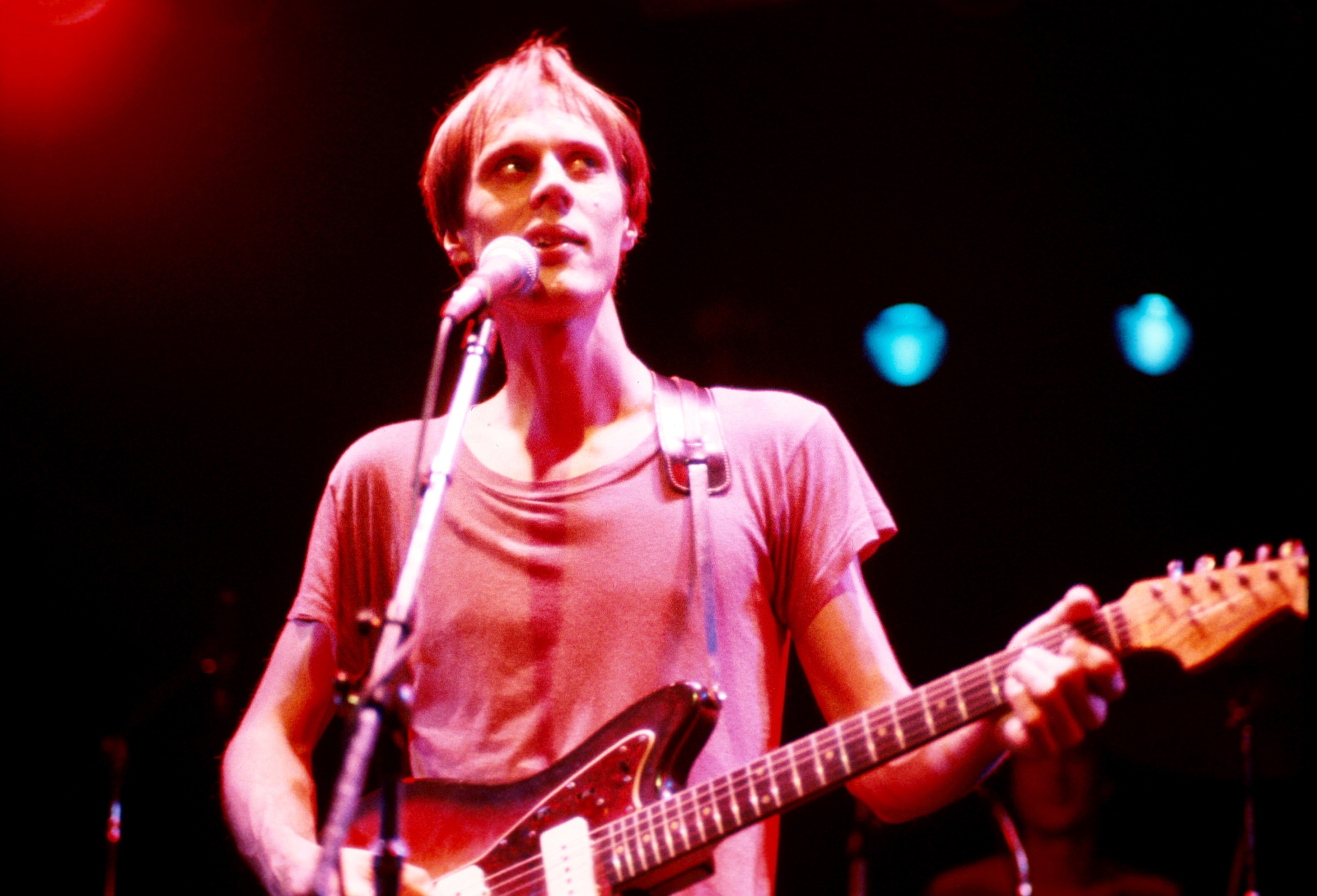

So much of what has been written about Verlaine since he died on Sunday at the age of 73 has resolved to this response—admiration verging toward awe, touched by a sort of wary confusion. Marquee Moon was the band's first album; they'd released a seven-minute single that covered both sides of a styrene record, and had the sort of prehistoric buzz around them that was won, at the time, mostly by playing shows at one of a few venues in one of a few cities. The critical consensus is that Marquee Moon is perfect, and that is my opinion as well.

By the time I first heard the record, I had started trying to figure all this out. It's probably why I first put it on. I was already bumping up against the limitations of my understanding. I could put some things in context; I could decode the simpler references; I knew who knew each other, and where they were from, and other things that seem more useful than they probably are. I knew what I couldn't understand, simply because I did not have access to the necessary materials, and so I worked on the things I could work on. And on its own and in the abstract, Marquee Moon could seem like one of those things—an album that is still decidedly separate from any scene or trend, but also a bridge between eras, and so on and so on. But that doesn't really get at the strange art of it, which is anxious and a little arch but also commanding and insistent and much harder to talk about. (It is also worth mentioning that Marquee Moon's sprawling title track remains arguably the greatest value in jukebox history; during the years between 2001 and 2011 I probably subjected the patrons of the two or three bars I went to most often to a cumulative 20 hours of the song.)

You can hear some of the acts that came before in that album, and how what was going on in their downtown Manhattan scene and the broader moment does and doesn't inform the band's music and perspective. It's there in the edgy discursiveness with which the band's playing pushes at the conventionally understood boundaries of a song, and in the musical and personal stylings that decorate all of it. You can hear the album in a great many of the acts that came after, too. But because there haven't really been many remotely convincing analogues how Verlaine and co-soloist Richard Lloyd played off and against each other, those comparisons don't illuminate much. It's just some stuff to know.

You can tell when a songwriter or a band has been influenced by Television, and weirdly it's not because their work sounds like Television but because Television sounds like them, before them. A lot of art works like this—if you read widely and write long enough, your writing will sound enough like the writers you care about that people will start mistaking all those voices for your own. Also there are things that it's foolish to try to imitate, because that imitation will only serve to highlight the distance between what you want to be and your capacity to reach it. Better, I think, to do what Forster did: take what you can from it, realize what of it isn't something you can keep, and then try to do something with the gratitude.

There should be more to Verlaine's story, probably. Where the rest of their catalogue should be is just dispute and a few stray facts. The band released one more (excellent, if lower-key) album in 1978, then broke up when Verlaine soured on the band; I don't know much about his solo projects, which persisted through the next decade and change, beyond that they were ambitious and ornery but not quite as ambitious or as ornery as his work with Television. The band released another excellent record after getting back together in 1993, and then never released anything else together, despite rumors of an all-but-finished album in 2011, and despite never officially breaking up. They played shows on roughly the same cycles that cicadas do, which were by most accounts both thrilling and strained. "The last time I ever saw [Verlaine] live was July 2018, at the Brooklyn club Elsewhere," Rob Sheffield wrote in his Verlaine tribute for Rolling Stone. "He was furious after the band played 'Marquee Moon,' complaining they made a mistake during his epic solo break. So he made them play it again—but only his epic solo break."

For all the things that have been written about Verlaine, it doesn't seem like anyone quite understood why he was the way he was. He was born in New Jersey and grew up in Delaware, got in trouble at school, took on a French poet's name and moved to New York. He was difficult to be around in the ways that geniuses often are, and could be cruel or dismissive in the way that geniuses can be; he ended friendships as suddenly and decisively as he broke up his band. Patti Smith, with whom he had a romantic and musical relationship in the '70s, wrote wrote tenderly about him in The New Yorker after his death, and also wrote some deliriously horny stuff about him in the magazine Rock Scene years before Marquee Moon. "The way he comes on like a dirt farmer and a prince. A languid boy with the confused grace of a child in paradise. A guy worth losing your virginity to. He is blessed with long veined hands." Smith loved him, and the two stayed close, but he seemed unknowable even by the standards applied to people whose fame or genius puts them at a remove from everyone else. His influences, when he'd discuss them, were mostly jazz musicians. He never married and had no children.

All of which is incidental, or just the sort of stuff that I tried to learn about geniuses like Verlaine before I realized that it would only ever get me so close. Whatever he wanted to say, or wanted anyone to know, is there in the songs, which drift and intertwine while holding their variously protean shapes and maintaining their strange and singular courses. "My favorite thing about especially the more meandering parts of Television," Steve Albini wrote, "was the way the music held onto a tonal center without having to frame it in 'changes' or 'heads' or even a fucking riff." I do not really know what that means, but I know that it is right, because I have felt it.

When I was younger, I thought I recognized the feeling of going out in the city in those songs, the sense of testing my new agency in an uncertain space; other people have made a similar observation. Now that I am older I think I was just feeling the deeper movement of the songs—their passages out into something unknown, and then back, and then out again—and trying, as anyone might, to see if there was something in that beauty that might have anything to do with me.