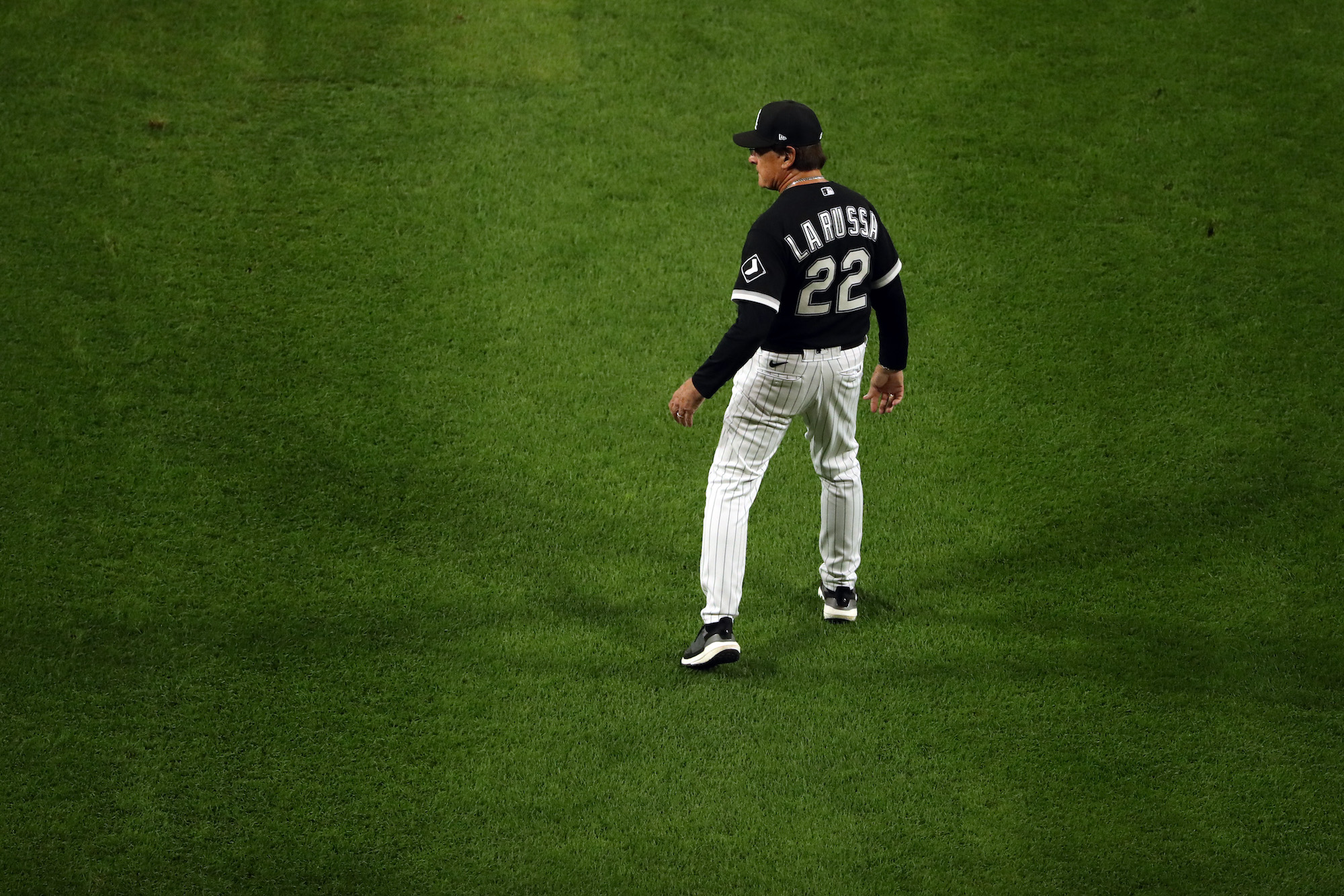

Tony La Russa saw the way the wind was blowing, albeit well after many others, and announced his retirement from managing. He cited heart issues as the main prompt, but he did not remove himself from the hook, which will please some of the grave-kickers.

"Our team’s record this season is the final reality. It is an unacceptable disappointment. There were some pluses, but too many minuses. In the Major Leagues, you either do or you don’t. Explanations come across as excuses. Respect and trust demand accountability, and during my managerial career, I understood that the ultimate responsibility for each minus belongs to the manager. I was hired to provide positive, difference-making leadership and support. Our record is proof. I did not do my job."

There are a lot of gaps to fill in here, but the truth is that La Russa was an indisputably superb manager for most of his 35-year career, but couldn't resist the call one time too many times, and waited beyond his best days to make one last belated comeback at the behest of his pal and benefactor, Jerry Reinsdorf. La Russa's rehiring after a 10-year absence was an indulgence for both men, a cry back to the days when managers actually ran the dugouts they populated rather than served as live-action message boards for the front office, and their mutual hubris bought them little credit for the team's 93-69 record in 2021 and significantly more derision when they fell back to their version of earth in the year just ending.

So let the shovels do their work. That's how the scam works; in the end, everyone takes one job too many, and when you're in charge in more than one place, you tend to start thinking that every room you enter is just there so that you can enter it as its smartest member. Like every other great manager ever, La Russa had a sense of his own infallibility, and in time his ability to hide it faded. He managed more games than anyone who never owned his own team, and that comes with its own self-packed baggage.

But La Russa was his own kind of innovator, starting with recreating the modern bullpen before it gave way to the demands of the opener, and managing every style successfully in Chicago the first time, then in Oakland and finally in St. Louis. He worked with and through the widest varieties of talents and egos any manger ever traversed, and for the most part stayed one step ahead of the sickle. He could be indulgent, as he was when Jose Canseco was traded while he was in the on-deck circle in 1992, and he could be petulant when questioned about strategy. He definitely became a symbol for post-modern play-the-right-way anti-modern authoritarianism, the guy once ahead of his time who defended his times after they became outdated. You may make of his drinking and/or driving peccadillos what you must; that's why you bought the Wiseass Knee-To-The-Junction Commenter Package.

Mostly, though, he was like any manager—beholden to the talent presented him. There is no WAR for managers, just standings, and La Russa's place in history works in conjunction with the player acquisition skills of Sandy Alderson in Oakland and Walt Jocketty and John Mozeliak in St. Louis, two teams that did the scouting/analytics thing in the proper proportions: as in, "Find talent, make numbers that fit the players they like." La Russa's gift was in finding what they did best and putting them in the positions that enhanced those skills. See Eckersley, Dennis, starter-turned-alcoholic-turned-sobered-alcoholic-turned-extraordinary-closer for an example. Even for those who found La Russa's work with bullpen restructuring an evil of the new millennium—and while it’s hard to remember, there were indeed those who despised the idea of “closers” and “setup guys” as newfangled fads—well, he's a manager, and for managers, there is only the next day and the next game. History is always someone else's problem because nobody ever got told, "You'll be considered a genius in 20 years but today you suck, so piss off."

In other words, La Russa was a creature of his times, and his times ended before his career did. He might have been remembered better by baseball's declining number of young'uns had he declined Reinsdorf's invitation to revivify the White Sox, but nobody ever realizes they're too old for the thing they've always done until they're too old for the thing they've always done. Sure, there were enough hints here and there, but when someone with money says you've still got it, you're a fool not to see if they're right. There are worse mistakes to make.