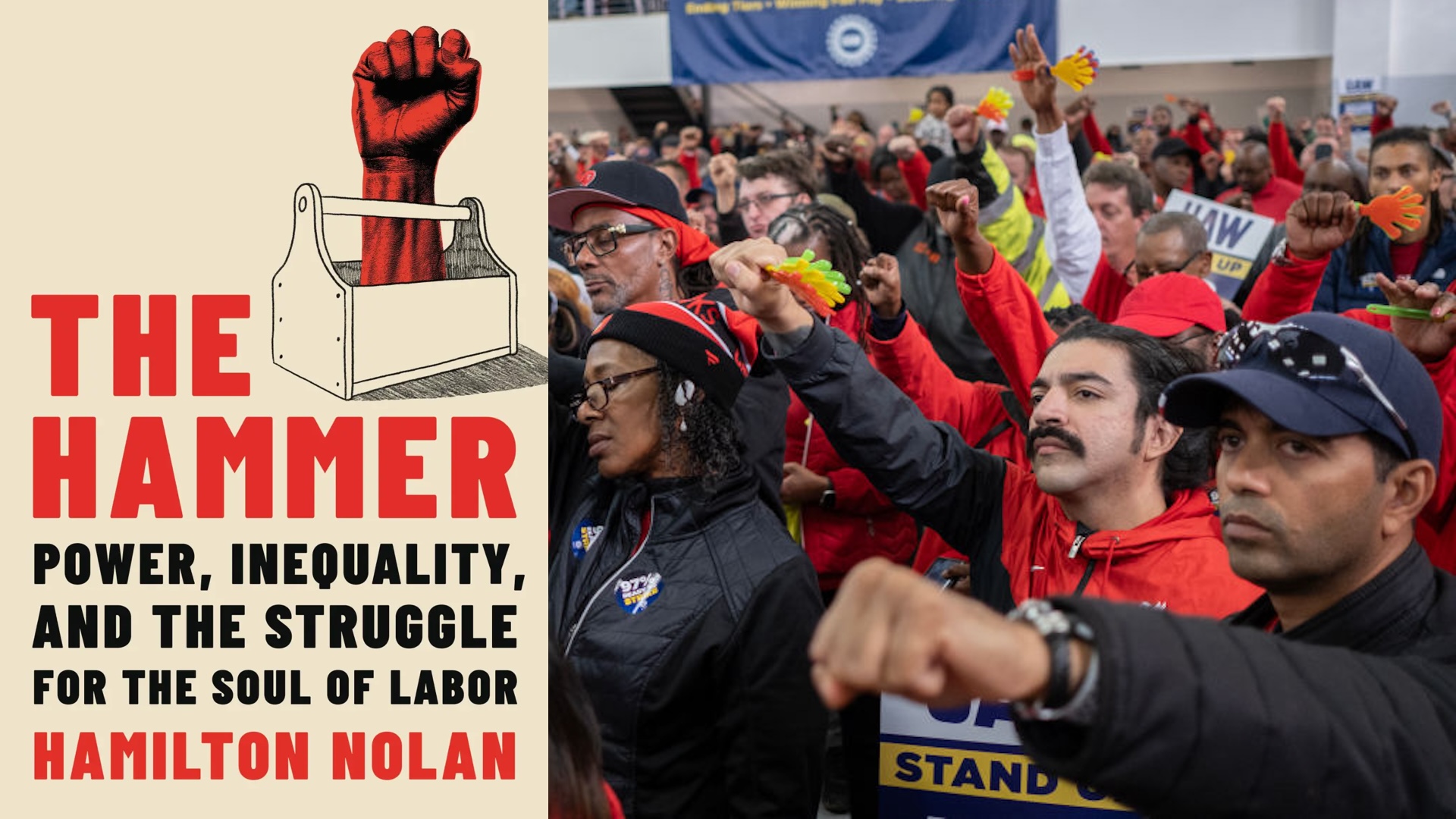

The following is excerpted from the last chapter of The Hammer: Power, Inequality, and the Struggle for the Soul of Labor, by Hamilton Nolan. The book is available for purchase now.

A union is a great way to meet new people, and argue with them. In a non-union workplace, you are obligated to blindly accept the boss’s decisions about pay and working conditions and every last policy governing life on the job. When you unionize, you earn the right to help decide these things, by arguing. Being active in a union can be thought of as one long period of argument, concluding only when you die. What do you think democracy is, anyhow?

The institutional enemy of the union is the boss, but in practice, most of the arguments you will have as a union member will be with your beloved fellow union members. To suddenly bestow upon a group of people the power to make collective decisions is to let a million arguments bloom. You will argue about what to ask for in the contract. You will argue about what to agree to in the contract. You will argue about when to walk out, when to strike, and when to send a strongly worded letter. You will argue about when the meetings should be held. At the meetings, you will argue. You will argue about the union logo, and the cut of the union T-shirts, and the union movie night selection. You will argue about union-wide policies of great importance, and you will argue about extremely minor matters inside your own workplace that can only be settled one way: argument. Sometimes, in an effort to turn down the temperature, you will temporarily refrain from arguing about something. But inside your head, you will be arguing still.

A democratic union has something of the New England town meeting spirit about it. Everyone will be afforded a voice, and a bunch of those voices will piss you off. The union speaks for all of you. Things must be voted on. If you want to send out a statement in everyone’s name, then by god you will listen to everyone’s thoughts about how that statement should be edited, long past the point of sanity or usefulness. Absurdly, the union is required to represent the interests of even those foolish members who disagree with you. And they will all have their say. Oh, you better believe it.

If you are lucky enough to be part of the founding of a healthy union, you will be able to witness the process whereby paralyzing arguments evolve into a functioning system for getting things done. This is a marvelous thing to see. With the help of experienced organizers, a group of regular working people can slowly come to the realization that perhaps having everyone argue about every single issue is not the most efficient way to operate. Some issues can be walled off into committees, where they can be argued about by a smaller number of people. Some issues can be delegated to elected representatives, who can only be argued with after they’ve already made their decisions. And, most astonishing of all, the entire group may—with time and bitter experience—stop arguing so much.

Not completely, you understand. But less. This is a democracy, not a utopia. I spent many nights sitting in council meetings at my union, listening to a famous television writer who used to be a journalist 30 years ago argue about what the journalists in our union needed to do. All the people there who actually worked in journalism today would tell him that in fact we needed to do the opposite of what he was saying. That would only make him redouble his efforts with longer and more self-referential speeches. This recurring bit of the democratic union experience often made me consider the virtues of Stalin’s methods of governance. I developed a months-long toothache due to the involuntary grinding of my teeth during these meetings. Still, in calmer moments I could admit that even this excruciating process was better than the alternative. In a dictatorship, the dictator might turn out to be that guy.

The union that began at Gawker Media in 2015 was notable for the fact that it would be impossible to construct a group of colleagues more prone to argue about everything. We were 100 or so people whose careers consisted of waking up each morning to write strongly argued pieces on the internet. “Here’s why I’m right, and you’re wrong, and by the way fuck you” was the job description. Naturally, we brought this approach to our early discussions about unionizing. Even in our left-leaning ranks, the urge to stake out the “this seemingly obvious idea is bad, actually” position was irresistible because many of us were so used to being professional contrarians. Describing in harsh terms why some popular idea or another was stupid made up a large portion of my own daily essays at that time. Battering opponents into submission with rhetoric was the only style of political negotiation that I knew. Attempting to organize a union was the first thing in my life that forced me to spend an extended period of time genuinely listening to the positions of people who disagreed with me and pissed me off—not for the purpose of crushing them, but for the purpose of understanding them. In other circumstances, their failure to acknowledge the brilliance of my arguments would have provoked nothing but a determination to bombard them with even louder arguments. If they still failed to agree with me, I could write them off as just another of life’s idiots. This is one of my own devastating personality flaws, yes, but it is also an illustration of how unions can force you to become a better person.

We are all lonely participants in this atomized world. The anomie of modern life and all that. Isolated by our cars and inhuman urban design and the collapse of organized religion and the algorithmic encouragement of tribalistic politics, we despair at the sensation of our nation descending into warring, alienated factions. All our differences seem to loom larger as time passes, to grow into unclimbable walls: red versus blue, young versus old, urban versus rural, affluent versus just scraping by, socialists versus the god damn fascists. We embed ever deeper into our little categories and assume that this is the natural order of things. We holler about “elites,” who might be anyone at all other than us. We accept this war of identities because we can imagine nothing more pure that exists to compare it to.

Try this: join a union. If you don’t have a union to join, make one. You can. It’s your right. I bet you’ll be surprised how good it makes you feel, even with all the arguing. There you are, sitting at work every day, griping about this and that. You get pissed at your jerk boss, at your too-low salary, at your paltry health insurance, at the grinding hours, at the incessant and unreasonable demands that commerce places upon your life. Everyone, with the exception of a small number of lottery winners, is annoyed at something about their job. Mostly, we are taught to suck it up. What is reinforced to all of us from a young age is not how to change the stupid decisions your boss makes, but to tolerate them. Stoicism in the face of hard work is fetishized. Your grandaddy and grandmother suffered, and your father and mother suffered, and you will honor them by suffering in the same way. Thankless hours for low pay? Character building! Sexual harassment on the job? We all went through that! Workplace injuries? Makes you strong! Decades of toil that barely allow you to pay the bills while a cabal of mediocre white guys who all seem to be pals with one another are in charge and make a lot more money than you despite exhibiting no real merit? It’s the way of the world! Stop your complaining! If you want a friendly ear, go whisper to Jesus. What makes you think that you should have it so much better than everyone else did?

The placidity that exists in the absence of a union is not evidence of happy peace; it is evidence of dictatorship. The absolute power of the company and the boss to determine everything about a job’s conditions is so common in America that most people never even think about it. It is widely seen as a state of nature. “If you don’t like the job, quit,” we are told, a sneering rebuke that leaves unspoken the fact that you will then become homeless. The idea that workers deserve to be able to have real power at work is fundamentally un-American. (Could Thomas Jefferson have run his successful plantation that way? Ridiculous.) It is a rejection of the cult of the business genius. We are trained to see our economy as one in which titanically gifted entrepreneurs launch flourishing companies that provide us, the grateful normal citizens, with jobs. Who are you to tell John Rockefeller or Andrew Carnegie or Henry Ford or Jack Welch or Bill Gates or Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk how to run their businesses? If you were so smart, you’d be as rich as they are, wouldn’t you? Stop being greedy for more, and start showing a little gratitude to these gods of capitalism. They are the mighty figures who pull all of society forward into prosperity. Progress, ho!

This mentality has always been drilled deep, deep into the bedrock of the American psyche. It still prevails. Men who love football and drive big trucks and prize nothing more than masculinity and strength will, without a moment’s thought, slip meekly into groveling servitude at the mere suggestion of anything that sounds socialist. It is what we are taught. For obvious reasons, unrestrained capitalism prefers that workers accept their place. Any increase in worker power is an interruption to the extraction of wealth from the world and its distillation into ever fewer hands. We all laugh at the sight of North Korean propaganda on the news, of an entire stadium full of people with pasted-on smiles dancing for the dictator. And then we go to work and do the same thing. Americans are still very much a nation of “temporarily embarrassed millionaires,” as the apocryphal John Steinbeck quote goes. To suggest that poor people should get more and rich people should get less and nobody really deserves a billion dollars often provokes a bizarre, outraged response in the public mind, driven not by any rational analysis of our common plight but by the unexamined conviction that the balm for our own suffering is for everyone else to suffer as well. I learned this by spending 20 years reading hate mail about stuff I wrote. But really, all you have to do is look around.

I was born in September 1979, just months before the dawn of the Reagan era. My lifetime is a tidy box containing the modern American age of inequality. From my birth until my 43rd birthday in 2022, the real income of the bottom 50 percent of Americans grew by less than 25 percent, according to data from economists at the University of California, Berkeley. That ain’t much. The real incomes of the top 10 percent of Americans grew by more than 150 percent during that time, the incomes of the top one percent grew by more than 250 percent, and the incomes of the top .01 percent grew by nearly 500 percent. On top of that, the productivity of the average worker in 2022 was more than 60 percent greater than it was in 1979, but that average worker’s wages had grown by less than 20 percent. Those two figures had grown in tandem from the end of World War II until the eve of the Reagan era, and then decoupled to the distinct disadvantage of workers. A Rand Corporation study found that the sharp upward divergence of income inequality beginning in the mid-’70s had, by 2018, cost workers $47 trillion—money they would have had if the historic levels of postwar equality had carried on as usual. That money went, instead, to the top 10 percent of earners. The class war has been fantastically profitable for its beneficiaries.

The rich have spent the past several decades redirecting more and more of the money that used to go to the working class into their own pockets. Federal Reserve data beginning in 1989 shows that that year, the top one percent richest Americans controlled less than 23 percent of the nation’s wealth; by 2022, they controlled more than 31 percent. The bottom 90 percent started that period with 40 percent of the wealth, and ended with 32 percent. The bottom 50 percent of Americans still have less than four percent of all wealth—which is to say, almost nothing, signifying how common a paycheck-to-paycheck existence is.

In 1979, union density sat comfortably over 20 percent. More than one in five American workers were union members. Today, it is less than half of that, barely one in 10; in the private sector, it is even worse at barely six percent. This decline, more than any other factor, is the reason why it has become so hard to sustain a middle-class lifestyle today. The sociologists Zachary Parolin and Tom VanHeuvelen studied the past 50 years of earnings data for American men and found that union membership resulted in an average of $1.3 million more in lifetime earnings—“larger than the average gains from completing college.”

Because unions raise wages not only for their own members but for non-members as well (as non-union firms are forced to compete with unionized ones for workers), this absolute loss in worker power has been magnified across the entire economy. The Economic Policy Institute estimated that if union density had remained at 1979 levels, the average non-union worker in the mid-2010s would have been earning $2,700 per year more. For workers without a college education, the financial hit was even greater. And that calculation doesn’t even account for the positive effects that the maintenance of union density would have had on the political power of the working class, during the era of corporate deregulation and anti-labor legislation that further exacerbated economic inequality’s rise.

Taken together, these figures tell a straightforward tale, one so simple that it should be included in America’s elementary school books: this country’s post–World War II balance of power between capital and labor—which produced, for three decades, the greatest shared prosperity that the world has ever seen—has become wildly tilted in capital’s favor. This skew has produced a level of inequality that has eroded faith in American institutions, warped our politics, and drowned the classic version of the American dream in a dirty puddle. After organized labor helped keep American production humming to win World War II, even conservatives accepted the vital role of unions in society. “Today in America unions have a secure place in our industrial life,” Dwight Eisenhower said in a 1952 speech to the American Federation of Labor. “Only a handful of unreconstructed reactionaries harbor the ugly thought of breaking unions.” By the 1970s, that attitude had been replaced with well-organized hostility from business, a hostility granted the full opportunity to flourish within legal and regulatory systems after Reagan assumed office. Today, the majority of American states, including an unbroken Southern front stretching from Texas to West Virginia, have “right to work” laws that make it difficult to build and maintain powerful unions in the private sector. Furthermore, all public sector unions have been rendered “right to work” by our right-wing Supreme Court. Many states severely restrict what public employees can bargain for, and make public sector strikes illegal or outlaw public collective bargaining entirely. And private companies that violate labor laws and use illegal tactics like firing, lying, and intimidation to stop their workers from organizing face laughably small penalties. The laws protecting workers when they organize are supposed to be enforced by the National Labor Relations Board, an agency that is overstretched and underfunded during Democratic administrations and actively weaponized against labor during Republican ones. Corporate power and its allies have quite successfully arranged America’s laws and prevailing culture so that, in most places, most of the time, working people are not taught about unions, must face great risk to their livelihoods to organize unions, and, if they do get unions, often find themselves mired in an endless bureaucratic struggle to secure a halfway decent contract from intransigent employers. Companies know very well that they can illegally union bust and refuse to negotiate in good faith. They have worked for many years to kneecap the government referees capable of preventing these things at a national scale. This sort of implacable determination that unions will not be allowed to exist or function has become the norm in corporate America. Any gains for organized labor must now be extracted with a hammer.

Capitalism is like nuclear power. It is a mighty force capable of producing great energy that can be harnessed for human progress—but if you don’t keep it tightly controlled, it will poison everything. The logic of capitalism is simple and relentless, a financial version of the sci-fi nanobots programmed to replicate themselves that end up turning the entire planet into gray goo. That logic pushes companies to maximize profits and, consequently, to push labor costs as close to zero as possible. It is a logic that is intensified with every level of economic abstraction, growing more prominent as you move from employee to business owner to investor to, at its peak, private equity and hedge funds and other investment vehicles that are completely removed from the human reality of what produces their wealth. Left to its own devices, this system will always trend in the direction of its final form, which is a tiny handful of incredibly rich people living in infinitely luxurious bubbles served by equally infinite armies of low-wage labor. A nation in which we have both a $7.25 per hour federal minimum wage and multiple centibillionaires building private space rockets to escape our overheating planet has already progressed a little too far down this dystopian road for comfort.

The project of distilling great wealth and power into few hands is always made harder by organized labor power. No matter how you brand it, the labor movement is fundamentally socialist. It works to empower the many, not the few; it tends to produce greater equality, rather than inequality; and the ability of global capitalism to achieve its preferred state of the world is limited in direct proportion to the ability of workers to reserve power for themselves. It is possible to imagine an enlightened form of capitalism that is happy to subject itself to democratic power-sharing and to spread its material bounty widely in the interest of collective peace. But in practice, though these conditions may flourish more in certain times and places, they will always be at risk from the demands that inexorably flow from shareholder capitalism. The profit motive is a simple killer robot that will never stop trying to take as much money as possible from labor’s pockets. It has a fiduciary duty, after all. Any overly optimistic approach to labor organizing that relies on building goodwill with business will, in the long run, fail. Capitalism and labor are cats and dogs. Each will revert to its nature in time.

Power. That is all that works. The hammer, not the handshake. The labor movement has always won things by fighting. It has taken what it has because it got strong enough to do so, and it has lost much of what it once had because it got too weak to keep it. Getting that power back demands, first of all, having the people—the people who are the workers who do the work that produces all the wealth, and who can withhold that work as leverage to get their fair share. Unions today don’t have enough of the people. They have been content to huddle on their shrinking islands for far too long. Ten percent of the workforce ain’t gonna cut it in a world of trillion-dollar corporations. We will organize more people, or we will anticlimactically wither away.