This week, Defector has chosen to curate a collection of writing inspired by two entities that have had an indelible effect on North America: the upper house of the United States Congress and Eugene Melnyk’s pro hockey team. This is Senators Week.

For the vast majority of human history, people lived relatively short lives, with United States life expectancy first exceeding 40 years old in the 1850s. That figure didn't reach 50 until the 1900s, and these days it's a little under 80. Yes, this increase can be attributed mostly to medical advances (compare our pandemic to, say, the Black Death), but we cannot count out the large-scale cessation of baroque idiots dying deaths that were, with the benefit of hindsight, funny as hell. Take for example the king of Sweden who supposedly ate too many treats and died, or the American sea captain who was obliterated during a 13-gun salute involving an accidentally loaded cannon. There was also the practice where upper-crust men used to settle their disputes by walking a bit before trying to shoot each other with shitty little guns.

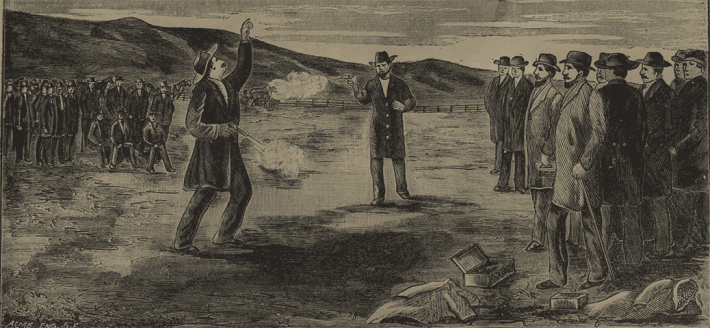

Dueling holds a strong place in early American lore, most notably when Alexander Hamilton was shot and killed by Aaron Burr over some letters Hamilton wrote about the then–vice president. (Burr's status as vice president at the time of the duel is one of the wildest parts of that story, though in the past, a person could simply ride their horse to a town 30 miles away and never be found by an agent of the law.) Dueling was a popular conflict resolution took for American men of means for roughly a century, from the time of the Revolution to the Civil War era. The practice traveled to the United States from Europe, where English and French nobles had enthusiastically shot or stabbed each other for centuries. In 1808, two French morons arguing over who could propose to a certain mademoiselle got into hot air balloons and attempted to snipe each other with blunderbusses. Though frequently illegal, duels often avoided prosecution, possibly because the participants tended to hold positions of power, such as United States senator.

Three U.S. senators died in duels, one of them while serving in office. Dozens more senators participated in duels through the years, including future President Andrew Jackson and Henry "The Great Pacificator" Clay. Here are the tales of the three fallen senators, in chronological order, as well as some other notable beefs in history.

Armistead Thomson Mason

Armistead Mason served as senator of Virginia from January 1816 until March 1817 after winning an election for the recently vacated seat of William B. Giles, who resigned to publish analog blogs for a while before becoming governor of Virginia. As hinted by his short time in office, Mason was not a particularly prominent politician. His only real distinction was that he was the second-youngest person ever to serve as a senator, taking office when he was a full year-and-a-half younger than the required age of 30. (The youngest has an infamous legacy of his own.) Once everyone found out about Mason's age, he agreed to resign after his term ended.

Mason then tried to run for Congress, though per the Congress's Biographical Directory, his "campaign of much bitterness" led to several duels. In 1819, Mason and his second cousin/next-door neighbor John Mason McCarty took the field after a yearslong dispute in local papers that featured Mason calling McCarty a "perjured scoundrel" and "an ass in lion's clothing," with McCarty writing that his second cousin had "paucity of talent which rendered him so conspicuously dumb in the Senate of the United States." Owned. Andrew Jackson, back in the Army between spells in office, reportedly told Mason to settle it with a duel, in which Mason wounded McCarty, while McCarty shot Mason through the heart. Both of these dummies were descendants of George Mason.

George Augustus Waggaman

Again, that goddamn menace Andrew Jackson plays a role in another dead senator's tale. George Waggaman, like Mason, fought in the War of 1812, serving under then-General Jackson at the decisive American victory in the Battle of New Orleans. He stuck around in Louisiana after the war, married into a family of sugarcane plantation owners, and worked as a lawyer. After he practiced law for two decades, Waggaman was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1831 following the resignation of Edward Livingston, Alexander Hamilton's old pal and the brother of Robert R. Livingston, who negotiated the Louisiana Purchase.

Waggaman's victory was a bit of a surprise, since he ran as an anti-Jackson candidate and defeated Livingston's cousin, a much more pro-Jackson politician. He served for four years, then went back to the gulf, where he got into a dispute with fellow Battle of New Orleans vet and former New Orleans Mayor Denis Prieur. The two men had serious political differences, and historical records say they fell out over what the papers called "some family affair, of long standing" or "domestic affairs." A report on the duel claims that Waggaman "received the ball of his antagonist in the fleshy part of his right thigh, through which it passed and buried itself in the left." The recap also states that Prieur was unharmed, and that Waggaman "is not considered to be in danger."

Wrong. Waggaman died two weeks later.

David Colbreth Broderick

If I were alive during the Civil War era, this guy would have been my senator. Unlike the two rich southerners above him, David Broderick died while actively serving in the U.S. Senate.

Broderick's father was an Irish stonemason who emigrated to the United States to help build the U.S. Capitol before the family moved to New York City. Broderick's biographer Richard Purcell wrote, "Of the child's early years, nothing is known," though he established himself in New York City by following his father into the masonry business, and serving as a volunteer firefighter (which he'd keep up with throughout his life). Broderick would open two bars: the Subterranean Saloon and the Republican. Through his businesses and his love of reading "widely in literature and biography," Broderick "gained an intimate understanding of men and of the intricacies of local politics." He was active in Tammany Hall, and nearly sought local office, though he was disillusioned that "hatred of foreigners and Catholics was becoming a dominant factor in New York." The year was 1849, so he struck west for California.

Broderick made some money minting five- and ten-dollar coins that only contained, respectively, four and eight dollars' worth of gold. I must tip my hat to a businessman. He also immediately got back into politics, which was defined by his vociferous opposition to slavery and exploitation in all forms. Even though the question was largely academic, Broderick successfully aided California's rejection of the Fugitive Slave Law. He also waged a campaign against the servitude of Chinese laborers building California's railroads, which pissed off the robber barons. "Such hostility to the interests of the ruling class made him an object of undying hatred," wrote Purcell. Broderick continued his fight as tensions ramped up throughout the 1850s, eventually culminating in what Purcell terms a "war" against California's pro-slavery U.S. Senator William Gwin, which only reached a truce when the revanchist Know-Nothing Party rose to power. Gwin and Broderick reached an alliance; Broderick was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1857. While in the upper house of government, Broderick voted against the tycoons and magnates of the day, attempted to secure payment to Native-American survivors of a massacre on the Oregon Trail, and tried to curtail the Department of War's influence in California. He was also one of only four senators to vote against Kansas becoming a slave state, which inflamed many powerful Democratic party honchos.

One of those was Chief Justice David Terry of the California Supreme Court, who during Broderick's campaign talked a bunch of trash about his opposition to slavery. In response, Broderick called him a dishonest judge and a "miserable wretch." Broderick's initial plan was to bait Gwin into a duel, and finally settle their internecine conflict, but almost immediately after losing his seat, Terry challenged Broderick to a duel and the senator accepted. The two men were both arrested by cops at their first meeting, for which too large a crowd showed up. Upon their release, they agreed to meet in secret on some guy's farm. Broderick's pistol fired prematurely, while Terry took dead aim and shot him in the chest. Three days later, Broderick was dead, claiming on his deathbed, "They killed me because I am opposed to the extension of slavery and a corrupt administration." Thousands marched for Broderick's funeral, including the entire San Francisco Fire Department, and Purcell attributes his martyrdom as a factor in helping Abraham Lincoln win California in 1860, while the Senate's official biography says his death "accelerated the downward spiral to civil war."

"'The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church'; and we mistake greatly, if the sacrifice of Mr. Broderick’s life will not be fruitful of revolutionary results in the popular mind," a local paper wrote. The Broderick-Terry duel was one of the last significant duels on American soil, achieving great cultural resonance, and haunting Terry until his death on a train in 1889, when he slapped U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Field in the face and was shot to death by the jurist's bodyguard.

Other Notable Duels Featuring Senators

• Though not officially a duel, Massachusetts Senator and staunch abolitionist Charles Sumner was nearly caned to death on the Senate floor by South Carolina Rep. Preston Brooks, a nasty idiot who was kicked out of his college for "threatening local police officers with firearms." Brooks was enraged by Sumner going after his cousin Senator Andrew Butler, another real piece of shit, who Sumner declared an "imbecile" and said "Senator Butler has chosen a mistress. I mean the harlot, slavery." Brooks was so mad he ran up on Sumner two days later and said, "You've libeled my state and slandered my white-haired old relative, Senator Butler, and I've come to punish you for it," before nearly killing him with his gold-tipped cane. Sumner couldn't return to work for three years, and Massachusetts let his sit seat vacant "as a reminder of southern brutality."

• Senator James Jackson of Georgia was in duels pretty much all the time; his biography refers to him as "a prince of duelists." He killed former Georgia Governor George Wells and fought federal agent James Seagrave, prominent Alabama plantation owner A.J. Pickett, and fellow Senator James Gunn, to name just a few. This man was always trying to shoot people.

• Andrew Jackson participated in over 100 duels, including one against Thomas Hart Benton, who he'd later befriend when both men were in the U.S. Senate. One famous victim was Charles Dickinson, who Jackson killed over a dispute about a bet on a race between horses names Ploughboy and Truxton after Dickinson called Jackson "a worthless scoundrel, a poltroon, and a coward." Jackson really benefitted from scheduling cupcake opponents for duels.

• U.S. Senator Solomon Weathersbee Downs of Louisiana was shot through both lungs during a duel. What's remarkable here is, once again, Andrew Jackson's role, though this time he served as savior. Downs was recovering when Jackson rode his horse by the house. This prompted Downs to suddenly stand up against doctor's orders, upon which the musket fragments were "forcibly ejected in the fit of coughing, and the wound healed immediately. Gen. Downs used to say that Gen. Jackson saved his life; for the exertion he made to get to a window to see the General pass, brought the paroxysm which resulted so well." Yeah, sure.