There's a lonely beeping at the edge of the solar system. Voyager 2, roughly 12.3 billion miles from Earth and zooming at 34,000 mph as it continues its one-way trip to the stars 46 years after launch, likes to check in with us to let us know how it's doing. It tells us where it is; it tells us what it senses around it (it lost its eyes decades ago); it tells us that it's still alive and hard at work. It is trying to tell us all that now, right now, but it can't. A couple of weeks ago, someone pushed the wrong buttons and told Voyager 2 to turn away from us, ever so slightly but enough to ensure that we can't hear it, and, most likely, it can't hear us. It is cold and dark out there beyond the heliosphere, and Voyager 2 is talking, and no one is listening.

It was surely someone's worst-ever day at work when on July 21, the scheduled commands sent out to Voyager 2 included some bad instructions. The probe, which like a good little probe was just doing what it thought we wanted it to do, turned its communications antenna two degrees away from Earth. Someone's performance review at NASA is not gonna be great this year. Since then, Voyager 2 has been futilely sending off its data into empty space, and we have been trying to reestablish some sort of contact with the probe. On Tuesday NASA finally announced it's picked up, faint but certain, Voyager 2's "heartbeat."

NASA knew where the probe was supposed to be, even after losing contact—after all, it's hurtling in a more or less straight line—and has had its Deep Space Network, an array of massive radio telescopes in California, Spain, and Australia, listening intently to see if it could make out a peep. It finally heard Voyager 2's carrier signal, even if it couldn't pick up the lower-frequency message signal embedded within, which contains the actual information Voyager is trying to send us.

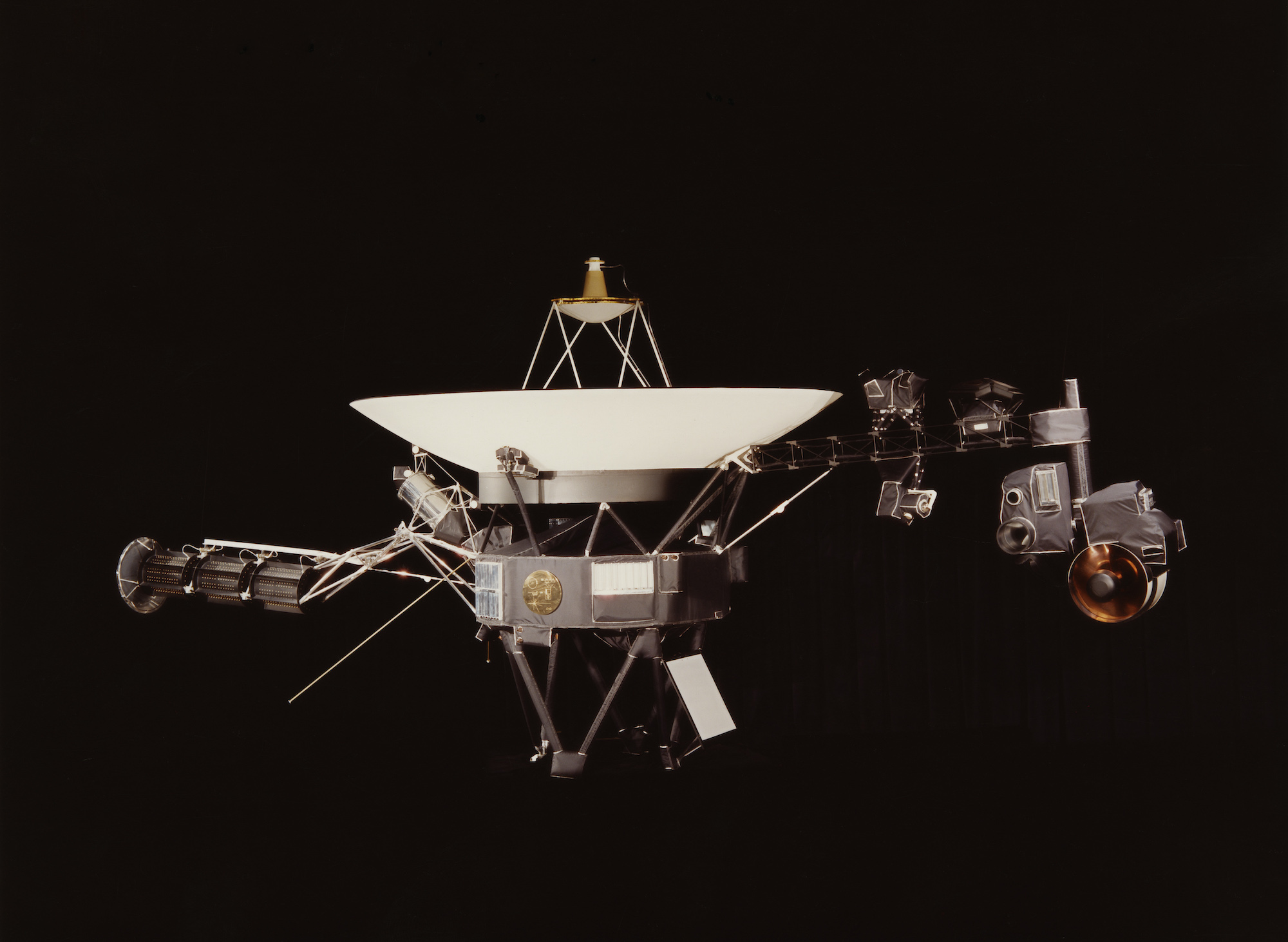

The Voyager program was and is a marvel of human optimism. The twin probes launched in 1977 each carrying a copy of the so-called Golden Record, a gold-plated copper phonograph record containing images and sounds and voices of life on Earth. It is a time capsule but for space instead of time, and like any time capsule, it's ostensibly meant to be opened but is more about its makers' faith that there'll be someone around to open it. "The spacecraft will be encountered and the record played only if there are advanced spacefaring civilizations in interstellar space," said Carl Sagan, who helped compile the playlist, "but the launching of this 'bottle' into the cosmic 'ocean' says something very hopeful about life on this planet." Something hopeful about life elsewhere too: Engraved on the record are directions to our solar system.

Voyager 2, on its way out, peered at Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune, and remains the only probe to have visited those last two ice giants. But though its primary mission was planetary, perhaps its most fascinating discoveries have been what comes after that. Scientists have long speculated about the location and nature of the heliopause, the edge of the bubble of the sun's atmospheric influence—in essence, the boundary between the solar system and interstellar space. Voyager 1 became the first man-made object to cross that border in 2012, and Voyager 2 followed in 2018, and both have been reliably sending back data on what it's like once you leave our solar island. (Lots of cosmic rays; lots of interstellar plasma, or ionized gases long-ago ejected from distant stars, coming from all directions; very few low-energy particles that originated in our own sun. It's unpleasant out there.)

Well, Voyager 2 was sending its data until we accidentally told it to stop. But there is hope! NASA is using its Canberra telescope to shotgun out a command to turn back toward us, in the hopes that Voyager's bad-angled antenna can still pick up a piece of the message. It's 18 light-hours each way, though, so they won't know the results of that command for another day or so; talking with Voyager is more like mailing a letter. And right now it's like mailing a letter to an old address, and the recipient hasn't opted into mail forwarding.

If that doesn't work, and it is a long shot, the real moment of truth will come on October 15. Voyager is programmed to regularly reset its systems, including realigning its antenna toward Earth, and if all goes well, it'll be chatting back to us like nothing ever happened.

Even if we get back in touch, however, Voyager 2's days are numbered. The onboard nuclear battery has gradually been producing less power, and to extend the life of the probe, NASA has been shutting down its systems one by one. Its visible-spectrum cameras went in 1990. (Voyager 1 took one last "family portrait" of the planets; 2's were powered down without ceremony.) It lost the ability to see in ultraviolet in 1998 and infrared in 2011. It lost its gyroscope in 2016. Voyager 2 is flying blind, and at some point in the next few years, it'll lose its eyes and voice too: All instruments are expected to lose power by the middle-to-end of the decade. It'll be a 1600-pound piece of space junk then, no longer transmitting or receiving, rushing headlong into the void, until 40,000 years from now when it will pass by the star Ross 248. If it sees anything interesting along the way, it won't be able to tell us.