Early in his research, Vukašin Bjelica found himself wrangling a hissing grass snake that he was elated to have captured. But when Bjelica attempted to take a close-up photo of the vigorously struggling snake, the snake suddenly went limp. Its mouth gaped and hung open, completely lifeless. "I was heartbroken," he said. "I thought I must have somehow accidentally hurt it and killed it." Bjelica returned the snake to the ground and was thinking about what to do when the snake suddenly came alive—flicking its tongue, raising its head, and darting away. "You can imagine my surprise," Bjelica said.

He would later learn that the grass snake's behavior was called, quite logically, death-feigning. When Bjelica began his PhD the zoology institute at the University of Belgrade in Serbia, he focused his research on dice snakes, an often aquatic relative of grass snakes with their own distinct approach to faking death. Hissing, struggling, and eventually going limp are not enough for the dice snake, which ups the gory ante by smearing itself in feces and a stinky musk, after which point the snake might dribble blood from its mouth. The belated bleeding intrigued Bjelica. Death feigning, a high-risk behavior that places the snake at high risk of being eaten if its ruse is discovered, usually occurs as a last resort after a snake has attempted other defense mechanisms. "Then after entering this rather enigmatic display, suddenly there is this display of hemorrhaging," Bjelica mused. He wondered if the bleeding made the snake's act more convincing, a question he put to the test in a new paper in Biology Letters.

Bjelica focused on a population of dice snakes on the island of Golem Grad, an island of nearly 50 acres inside a lake in North Macedonia. The island is notably home to the ruins of a handful of ancient churches and also approximately 10,000 dice snakes. The snakes of Golem Grad are most notable, however, for their penchant for feigning death and spontanously bleeding, behaviors recorded more frequently in this population of dice snakes than others. On Golem Grad, dice snakes come in olive green, blotched, or a darker melanistic color, and their sheer abundance makes them easy to spot, and catch. "Sometimes you can see them basking in the sun on a rock and you can just grab them," Bjelica said. " Or they're resting on a tree branch and you just climb up and get them."

Over the course of a year, Bjelica and colleagues caught 263 unique dice snakes on Golem Grad, snagging them from their basking rocks and branches or even swimming around the lake. He wore protective gloves—not for the snakes, which are nonvenomous, but for the island's sharp rocks and thorny Mediterranean vegetation. Also, the island is home to another, actually venomous snake: the nose-horned viper, named for the prominent horn on its snout.

After catching a snake around its midsection, the researchers would hold the snakes behind their head and above their cloacae, alternating between pinching the snakes and stretching them out. The behavior was intended to imitate one of the snake's predators, such as one of the islands' snake-eating birds. "Pinching was designed to simulated claws gripping the snake, while stretching was aimed at imitating the bird stretching the snake to get to the large organs such as the liver," Bjelica said. After the handling ritual was complete, the researchers placed the snake on its back on the ground and scampered out of view, to mimic a predator's hesitation to eat its prey. They timed the snake's response from the second it was left alone and watched as the animal feigned death, and how.

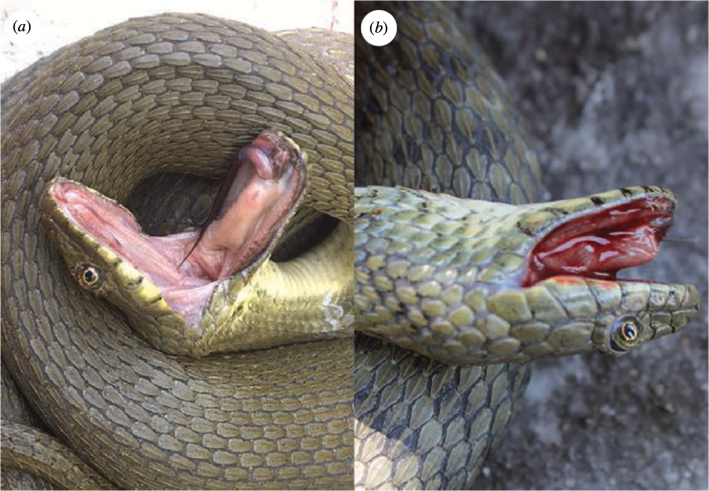

Nearly half of the snakes smeared themselves in musk and their own waste, a strategy that can convince the predator that the snake is unpalatable—quite literally smelling and tasting like shit. Watching this was an unsurprisingly smelly experience. "The amount of feces can be extreme," Bjelica said. "More often than not, after each field day you can always do with a wardrobe change." And just over 10 percent of the dice snakes ejected blood, a behavior Bjelica finds "always exciting." The bleeding always occurs around the mouth and is, thankfully for the researchers, not squirted toward a predator. "The blood comes out slowly, first as individual spots then grouping into larger pools," he said.

Although all the snakes played dead, some committing to the bit for as long as 40 seconds, the snakes that used musk, poop, and blood in their performances spent, on average, two seconds less faking their death. This might sound like a trifling amount of time, but for a snake staring down the jaws of a hungry bird, it can mean the difference between life and death. Feigning death requires the serpent to lie with its delicious, soft tummy up for inspection by its greatest enemy. The more convincing a snake's act is, the less time it needs to spend in mortal danger, the researchers suggest.

But they are still left with questions. Bjelica wonders about the chemical composition of the snake's musk and blood. "Are they harmful to the predator or just distasteful?" The researchers do not know if a dice snake's mouthful of blood is a visual signal, a chemical signal, or both. They do not even know the mechanism by which a living snake can dribble blood from its mouth. But as Bjelica sees it, the most significant takeaway from the research is that the dice snake's death-feigning display on Golem Grad is a multi-step spectacle, of blood and from guts, and should be studied as such. Regardless of whatever dice snakes are doing elsewhere in Europe, Golem Grad has set a high bar for the age-old technique of faking your death. Other death-feigners, take note! Sometimes committing to the bit is the only way to stay alive.