I still remember the first time I learned about Saccorhytus. I was scrolling through a gallery of images related to new scientific papers when I saw an illustration of something ovoid, magenta, and unsettling. My mind swirled with questions. Who or what was this captivating being? The attached press release, titled "Scientists relieved to discover ‘curious’ creature with no anus is not earliest human ancestor," only left me with more questions. Relieved? Would it really so bad if such a creature were our ancestor? I had not spent much time imagining what, exactly, our earliest ancestor looked like—blobby, maybe?—but it wasn't not this.

I do not remember why I did not write about Saccorhytus then. Maybe I was busy, tied up with other stories. Maybe I thought the kind readers of Defector would have little interest in learning that a 500-million-year-old fossil they'd never before heard of wasn't actually our earliest ancestor. For whatever reason, I let the news cycle of Saccorhytus waft by, like the scent of pine needles on the sidewalk. But I never forgot Saccorhytus. How could you forget something so strange, so severe, so flamboyantly magenta? So this week, when I was skimming through a list of new papers, I was overjoyed to see there was a new one about Saccorhytus. My old friend! I DM-ed Barry, my editor, to ask if he remembered Saccorhytus, as I was convinced the little pink fossil had gone viral. But he had not heard of Saccorhytus.

In this blog, I hope to offer an exhaustive timeline of our understanding of Saccorhytus in the public and scholarly imagination since the fossil was first described in 2017. Who was Saccorhytus, this ancient shapeshifter whose enigma revealed more about us than of itself? Why does it look like that? And would it truly be so bad if we were related?

The World Learns Of Saccorhytus And Is, Presumably, Intrigued

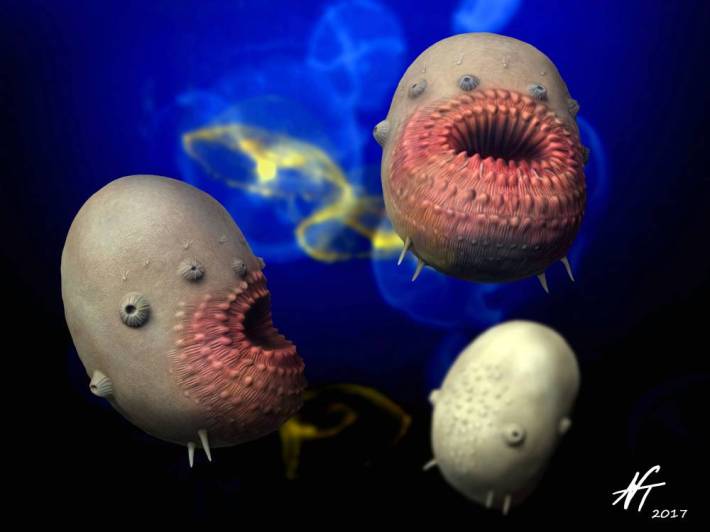

In 2017, a group of researchers from the University of Cambridge in the U.K. and Northwest University in Xi'an, China, published a study in the journal Nature describing a sea creature that lived about 535 million years ago. It was extremely tiny, just a millimeter in diameter. The researchers named Saccorhytus coronarius after its "bag-like body" (saccus in Latin) and wrinkled appearance (rhytus in Greek.) And coronarius was in reference to its crown-like mouth, which consisted of two circlets with an array of folds and protuberances. These researchers also released the first reconstruction of Saccorhytus as a greenish egg-shaped creature with a mouth seemingly opened in a perpetual scream.

Looking at the photos of the fossils themselves, which appear wrinkled and deflated, it seems the artist was kind enough to inflate Saccorhytus to how the creature may have appeared when alive. The authors suggest Saccorhytus's thick but flexible cuticle would have allowed the tiny creature to wriggle between grains of sand at the bottom an ancient shallow sea that is now the province of Shaanxi, China. They admitted it was possible to interpret Saccorhytus as either a miniaturized adult or a larval stage, but chose the adult interpretation because most larvae are encircled by tiny hairs called cilia and have much thinner cuticle coverings.

The study's grandest claim was not Saccorhytus's developmental age, but its lineage. The researchers argued Saccorhytus was the earliest example of a large group of animals called deuterostomes—"mouth second" in Greek. Deuterostomes have this name because in embryonic development, the first hole they form is their anus, followed by their mouth. (The other group, the protostomes, form their mouth first, and then their anus.) We vertebrates are deuterostomes, along with some invertebrates including sea stars, sea urchins, and sea cucumbers. The researchers concluded the ring of holes around the creature's mouth were precursors to modern gills, a feature of deuterostomes.

Scientists had discovered even earlier animal fossils. But none were deuterostomes. So if their hypothesis of the half-a-million-year-old Saccorhytus was correct, the creature would represent the earliest known ancestors of modern humans. Pretty exciting!

Strangely, however, none of the Saccorhytus fossils appeared to have an anus, suggesting their big mouth really does do it all. Simon Conway Morris, a paleobiologist at the University of Cambridge and an author of the Nature paper, told The Guardian that it was possible his team had simply not been able to identify the anus, but noted that other simple creatures, such as worm-like marine invertebrates called acoels, are anus-less.

After the press around this paper died down in 2017, the world seemingly moved on from Saccorhytus ... that is, until 2022.

The World Seemingly Rejoices When Saccorhytus Is Revealed NOT To Be Our Ancestor

In 2022, a group of researchers from Chang’an University in Xi'an, China, and the University of Bristol in the U.K. took another look at Saccorhytus and determined the creature was not, in fact, the first known deuterostome, the first known creature from which all of us humans descend. Instead, the researchers hypothesized Saccorhytus belonged to a group of protostomes, the "mouth-first" animals, called the ecdysozoans. This group includes animals that grow through a series of moulting stages, including modern arthropods, nematodes, and some other smaller groups of animals. The researchers published their alternative interpretation of Saccorhytus in Nature.

This group of researchers looked into many other possible identities for the little sac, including corals, anemones, jellyfish—living animals that have a mouth but no anus. But they ultimately arrived at their conclusion after taking a slew of X-rays of many Saccorhytus fossils at various stages of decomposition, eventually reconstructing a 3D digital model of the fossil (the magenta headshot at the top of this article). These were not ordinary X-rays, but very intense X-rays taken with a type of particle accelerator called a synchotron. The resulting model suggested that the ring of holes around Saccorhytus's mouth were actually a series of broken spines. The researchers suggested the creature may have relied on these spines to capture prey. The press release of this paper stated that scientists were "relieved" to discover Saccorhytus was not our ancestor.

So was the identity of Saccorhytus settled, at least for now? Karma Nanglu, a paleobiologist at Harvard University's Museum of Comparative Zoology who was not involved with either paper, told Live Science that he didn't see the new paper as a "full-on correction" of the old one. "It's an alternative interpretation and I think both of them are interesting and worthy of debate," he said. And with that, the tale of Saccorhytus dropped off again, at least in the public eye. But behind the scenes, another scientist was working on a new interpretation of our favorite old sac.

The World Keeps Spinning On As Saccorhytus STUNS In New Interpretation

This month sees another interpretation of the sac-like creature, this time published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B. The paper's sole author is Jean Vannier, a researcher at the University of Lyon in France. Like the authors of the 2022 paper, Vannier was not convinced by the original interpretation of Saccorhytus. He agreed that the sack was much more likely to be an enigmatic ecdysozoan. But something was still bugging him. "Although this interpretation made much more sense, the anatomical enigma of Saccorhytus remained," Vannier wrote in an email, adding that there were still no modern or fossil ecdysozoans that looked quite as strange as Saccorhytus.

"The problem with Saccorhytus is not the bag-like shape but how this organism could live," Vannier said. He wondered how a bag with a mouth but no anus could have moved around its environment or managed to eat. "The previous papers were very vague on this," he said. It's true that modern ecdysozoans use their mouths to grasp food. But Saccorhytus's mouth-spines had the wrong orientation to grasp food, as well as no organ that would have allowed the creature to retract them, Vannier said.

Then he had a breakthrough: All the prior papers considered this animal an adult. But what if it was a baby? "My opinion was that it could represent a larval stage which by definition is constructing its final body organization," Vannier said. He began looking at the larval stages of modern ecdysozoan worms to see if anything looked like Saccorhytus. Perhaps the most obvious candidate was the penis worm, meaning the marine worms in the phylum Priapulida. The worms were abundant in the Cambrian period and still survive today, although they are very rare.

Vannier was familiar with penis worms, as he had previously collected and studied them in Sweden and northern Russia. He knew the shape of the worm's larval stages often looked wildly different from their adult selves. After the worm Priapulus caudatus, it experiences three larval stages. The first, post-hatching larva is less a worm than a sack. "It cannot feed and use stored nutrient until it develops the ability to catch food," Vannier said. The larval sack does not have an anus, nor a functional mouth, but it does have an opening through which the next developmental stage will exit. This, Vannier argued, was what Saccorhytus might have really represented: the youngest possible version of an early penis worm, or something like it.

But which ancient worm would Saccorhytus become? Vannier began reading about the various worms that had fossilized in the formation in China where Saccorhytus was collected and identified several plausible candidates, including Eokinorhynchus rarus, which scientists hypothesize is an early member of a group of worms called mud dragons, and a tiny worm called Xinliscolex intermedius. "It was important to look at these worms because they might have been potential candidates," Vannier said, adding that some of these worms have large spines around their body that can be matched to Saccorhytus's spines.

Jian Han, a researcher at Northwest University in Xi’an and an author on the very first Saccorhytus paper in 2017, said he was aware of Vannier's interpretation. "Jean told me his thoughts last year," Han wrote in an email, noting that the theory of an unfeeding larva is not new, but one he and his colleagues excluded in 2017. But this year, Han and Vannier collaborated on a new paper in eLife describing a new, sack-like species of early ecdysozoan, Beretella spinosa, that is a sister to Saccorhytus.

A Saccorhytus Denouement?

Has the investigation into the real identity of Saccorhytus finally concluded? In short, no. Vannier's interpretation is one of several, none of which have been conclusively proven or disproven. This is the nature of paleontology. "We just shed new light on ancient animals, but it is clear that we might be wrong sometimes," Vannier said. But he says his interpretation shows the value of comparing fossils to modern animals. "What paleontologists sometimes forget is that the fossils they study were once living animals," he said.

We may never know exactly who Saccorhytus was, how it lived, or if it ever ate or moved or pooped. New and future technologies may bring us closer to the heart of the mystery that is this wrinkly, gaping ball-sac-like creature. And even if we are ultimately not related to Saccorhytus, I hope we can find space within our hearts for such a special creature that has captured the hearts and minds of so many [Ed note: citation needed]. I know it will be stamped forever in my mind as the most beguiling sack that ever lived.