Space is so hot right now. The uncrewed Artemis I mission is on its way to lunar orbit, the first in a series of missions that plans to return humans to the moon by the end of the decade. A spacewalk at the International Space Station went down this week, and it was streamed live. We're hucking shit at asteroids to prove we can. And our new friend the James Webb Space Telescope is just doing its thing, quietly overhauling our entire understanding of how the universe works.

The JWST is floating a million miles from Earth and sending back images that make the Hubble look like a real piece of shit. Understandably, the pictures from Webb that get the headlines are the mindblowing ones—the photos that are particularly beautiful, or magnitudinous, and inspire awe. Webb is still taking plenty of those. But those more artistic images are, in some sense, the telescope doing PR to justify its existence to the broader public. The actual science takes place in the analysis of the less sexy data: stuff that's not even on the visible spectrum, or in the close parsing of relatively unspectacular photos. Yesterday's big news comes from those workaday images.

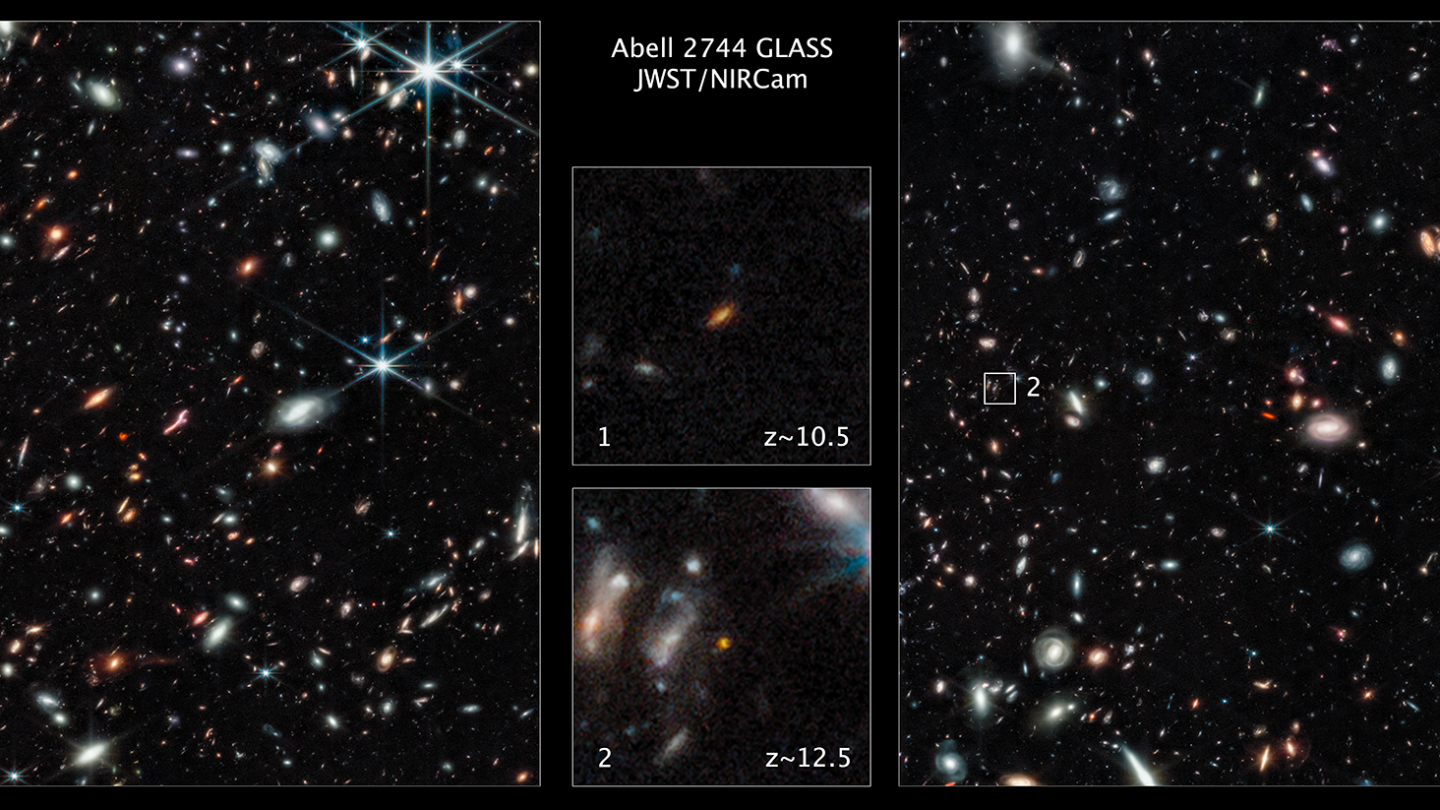

I realize I risk underselling this, so: Of course these images are spectacular, even if they're no Pillars of Creation. And what they show—namely, what's blown up in Figure 2 at bottom center—is a brain-melting superlative. It is galaxy GLASS-z12, and it is believed to be 13.45 billion years old, or just 350 million years after the universe was created in the Big Bang. It is the most distant starlight we have ever seen.

But it is not the existence of the galaxy that has scientists so excited—we already knew that there would be galaxies from around then, and we knew that the JWST's superior imaging would reveal them. What was unexpected was how easy it was to find.

“Based on all the predictions, we thought we had to search a much bigger volume of space to find such galaxies,” said Marco Castellano of the National Institute for Astrophysics in Rome, who led one of two research papers published Thursday in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. Scientists had a model, based on current understandings, for how many of these bright, fully formed galaxies in the very early days of the universe would be out there. That model predicted that a slice of sky about 10 times larger than what Webb captured would be required to find them. Instead, Webb quickly surveyed two such galaxies, which scientists discovered within just a few days after the data was released for study.

What this implies is that our models were wrong, and that bright, populous galaxies might have formed faster and more frequently after the end of the stellar dark ages—about 100 million years after the Big Bang, when the conditions in the early universe finally allowed gravity to start building stars—than we had ever imagined.

We were wrong! That's so cool! Learning we were wrong is, like, the whole literal point of science! Knowing our models and predictions were inaccurate allows us to make new ones to better explain the observations, moving us ever closer to being right. Science is iterative, and these small discoveries, rather than the big splashy images, are how the JWST will help us write and rewrite the early history of our universe.

“These observations just make your head explode," said Paola Santini, a co-author on the Castellano et al. paper. "This is a whole new chapter in astronomy. It's like an archaeological dig, and suddenly you find a lost city or something you didn’t know about. It’s just staggering."

These two new, young galaxies are already providing some intriguing observations. Namely, they are far brighter than we expected them to be, and brighter than anything else we have closer to Earth. "Their extreme brightnesses are a real puzzle," said Pascal Oesch, a co-author on the second paper published today. But there is an appealing possibility. It's hypothesized that in the very early universe, stars would have been composed of only hydrogen and helium, simply because they had not yet had time to produce heavier elements by nuclear fusion. Those so-called Population III stars would be incredibly hot and incredibly bright, and while they've long been theorized, they've never been observed. Until, perhaps, now.

This is, in every sense, hot shit. Thanks, Webb.