Let's say you're in space. Probably a lot of things would have to go horribly awry for this to be the case, but just go with it. Things aren't magically different there: You still get thirsty, and you still need to wash yourself, although you'll do that much differently and less frequently than you currently might. If you have animals on board they will need to drink, too. This means you need water. Water! Elixir of life. Wetter of whistles. But a thing about water is that there's not much of it in space, pretty much by definition. So what do you do if you're on an extended mission, say, spending a few months on the International Space Station, or (someday) zipping the 12 light years to Tau Ceti?

Well, you have to bring it with you. There's not really a way around that. Currently, water is flown into space in 90-pound bladders called Contingency Water Containers, which look more or less like duffel bags. A few of those on a resupply mission may sound like a lot of water, but once it's up there, that's what you've got to work with. So you've got to try to make that water last. And that means you can't just be throwing out all that valuable urine.

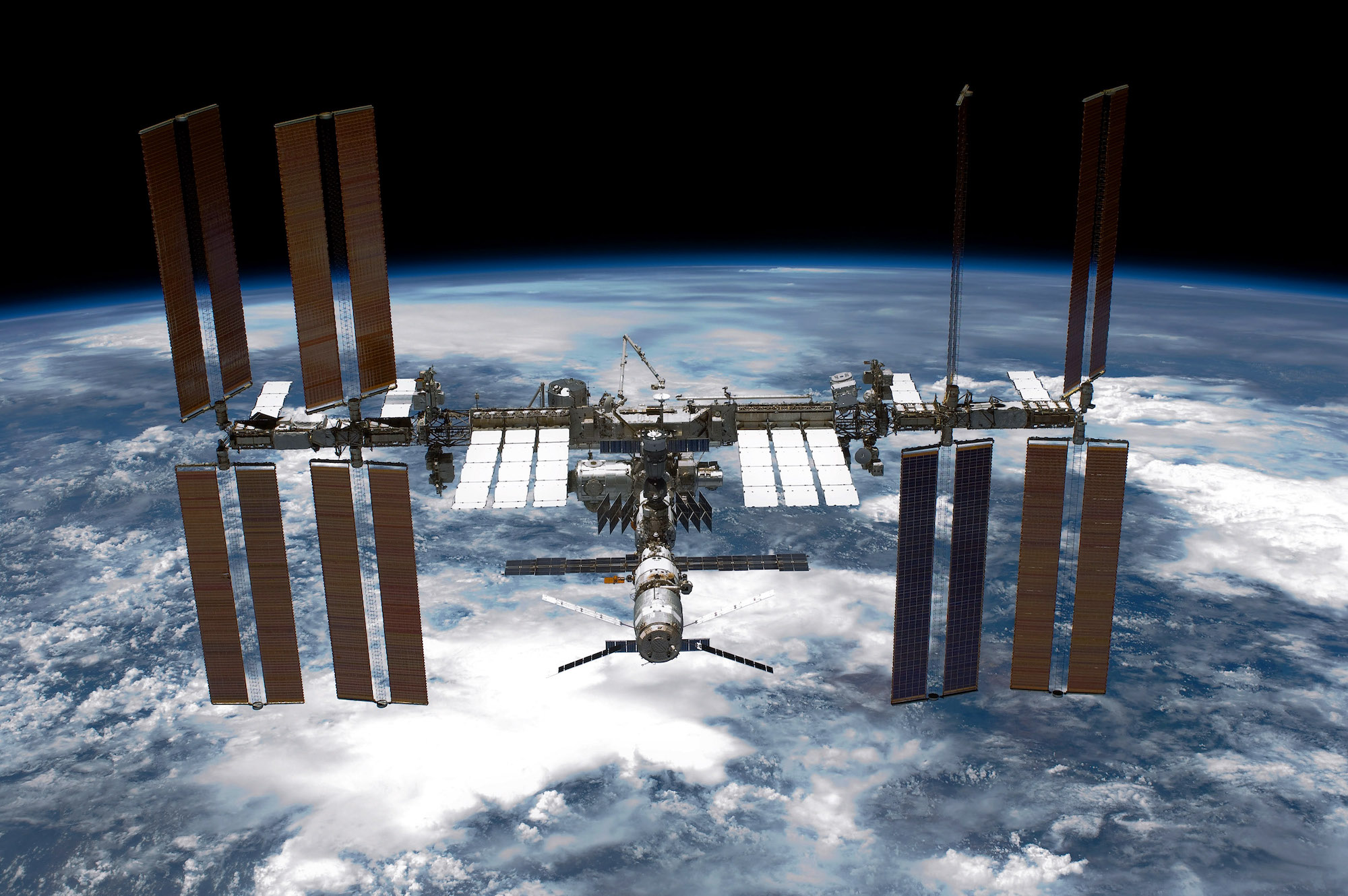

The ISS has two water recycling systems on board. The first is environmental: The Water Processor Assembly dehumidifies the air on board, removing the moisture that's constantly released through crew members' sweat and breath. Then there's the Urine Processor Assembly, which is exactly what it sounds like. When astronauts use the fancy new $23 million toilet, installed just three years ago, they pee into a vacuum hose, and their urine is then distilled into—mostly—clean water.

It's a good system. It has recovery rates around 93.5 percent, which means that most of the water that's initially brought on board can be used again and again. But what if it could be better? What if there was even more gold in that there piss?

The UPA produced drinkable water but also the unappetizingly named urine brine. Enter NASA's Brine Processor Assembly, which was launched up and installed in 2021. The BPA takes the previously unusable urine brine, pumps it into a dual-membrane bladder which filters out even more of the nasty bits, then blows warm, dry air over it to evaporate the moisture from the brine. This moisture is captured from the ambient air by the WPA, making it re-re-recycled water. In theory, the BPA could reclaim 80 percent of that brine. But no one was quite sure how efficiently it would work in microgravity.

Works pretty well, it turns out. After a couple years of testing, NASA has announced that the system has improved ISS's overall water recovery rate to 98 percent, which was the target for long-duration missions, to other planets and beyond.

“The regenerative ECLSS systems become ever more important as we go beyond low Earth orbit,” said Jill Williamson, ECLSS water subsystems manager. “The inability of resupply during exploration means we need to be able to reclaim all the resources the crew needs on these missions."

It's a big deal. There are two basic things we can't survive in space without: power and water. We can capture or generate the former through solar arrays or reactors; for the latter, we're stuck with packing it. And while getting anything into low-earth orbit is expensive enough already, when we really head out to explore the solar system, every inch and every pound is going to count; we can't be putting a SeaWorld tank in there, and we won't be able to top it off with earth water when it gets low. The water on board when the mission starts is the water that's going to have to complete it, and NASA believes that a 98 percent recovery rate for that water is a workable one.

NASA would like to make one thing clear, though: The astronauts are not drinking piss.

“The crew is not drinking urine," Williamson said, "they are drinking water that has been reclaimed, filtered, and cleaned such that it is cleaner than what we drink here on Earth."