When Stella Walsh was shot and killed in a parking lot in 1980 while doing her holiday shopping, nobody thought it would call her Olympic medals, won nearly 50 years earlier, into question. But when the coroner’s report was leaked and publicized on local TV stations, people started talking.

Due to that violation of her medical privacy, we now know that Walsh was likely intersex. The story blew up; reporters even showed up at her funeral, asking questions about her genitals, only to be shouted down and pushed away. Today, Walsh’s name appears on every list of intersex athletes. It’s a list she never wanted to be on. According to friends, she spent her whole life hiding her body from colleagues, teammates, and family members.

I’ve spent the last five years reporting a podcast documentary series called Tested about the past, present, and future of sex testing in elite athletics. Along the way, I found myself constantly struggling with questions about just how much I really deserved to know about the bodies of athletes, particularly those who were no longer living and could no longer consent to me sharing information about their biology. How do our decisions as journalists telling these stories impact the lives of modern athletes who are still being excluded, and stigmatized, for their bodies?

Half the joy of sports is the narrative. Fans are drawn to hidden truths, surprising backstories, and reexamined legacies. We crave intimate glimpses into the real lives of the people behind these incredible feats of strength, speed, and agility. We’re suckers for stories, and it can be just as exhilarating to watch a legacy be debunked as it is to watch one be built. But where does one draw the line?

Stella Walsh is not the only athlete to have her sex scrutinized, potentially against their will. During the reporting process for my podcast, I requested a police report from the German National Archives for an athlete named Heinrich Ratjen. Ratjen competed as a woman in the 1936 Olympics, and has long been held up as an example of a man disguising himself in order to compete as a woman, perhaps even as part of some nefarious Nazi plot. Ratjen’s actual history is much more complicated: He likely fit a contemporary definition of intersex, and was raised as a girl after being assigned female at birth. One day on the train home from a track and field event, he was accused by police of being a man dressed in women’s clothing. At the police station, records show that he reported being almost relieved at the accusation, and he later disappeared into a new life as a man.

When I opened that police document, I was surprised to find a full-body nude photograph of Ratjen in heels. Reading papers about him, you’ll find historians using these photos and the police report to speculate about his genitals, debating whether or not Ratjen was intersex, or actually a “biological male” his family chose to raise as a girl for some reason.

There’s also the story of Foekje Dillema, a Dutch track star from the 1950s, who had a genetic condition called “46,XX/46,XY mosaic condition.” We only know this about her because after her death, her family gathered up skin cells from her clothes and commissioned a study about her biology. Dillema had already been humiliated once: In 1950, she refused to undergo a “gender verification” test, which at the time would have been an invasive physical examination of her genitalia. When she declined the test, the International Association of Athletics Federations (now known as World Athletics) banned her from competition and stripped her of her medals. According to one biography, she returned home and didn’t leave the house for over a year. Dillema kept the secret of her biology for 60 years, but now it is public information, available to anybody with an internet connection.

Every time I came across an example like this in my research, I felt many conflicting feelings about it. Should we really be “uncovering the true sex” of these athletes after their deaths? Whose business is it what Ratjen or Walsh’s genitalia looked like, or what was going on inside of Dillema’s cells? Why are people so set on uncovering the “truth” behind these athletes who were already ostracized and, in some cases, kicked out of sports while they were alive? Who does it serve to know this information? Does it matter that these women never wanted this to be known? Is it better to tell these stories than to keep them hidden?

Because Walsh and Dillema were dead when the details of their biology came to light, they can’t speak for themselves. Instead, sports coverage collapsed the complexity of their stories into “controversies” or “scandals.” It’s sexier that way; the revelation of a “hidden truth” about a famous athlete is like catnip for journalists and fans. What gets lost in these flattened histories is any meaningful understanding of the lives these athletes lived. We also lose the chance to think critically about how these past “scandals” are still today affecting athletes with variations in sex biology.

In 2023, the governing body of track and field released new policies regulating women they call “DSD athletes," athletes with differences of sex development. If women who are deemed to be members of this category want to continue competing at the elite level as women, they have to manipulate their body’s biology and lower their naturally occurring testosterone levels. Some women, like Tokyo 200m silver medalist Christine Mboma, have chosen to do this. Others have refused and are taking World Athletics to court. These rules are the latest in a string of testosterone-based regulations that have affected athletes for over 10 years—the most famous of whom is South African runner Caster Semenya.

Semenya herself is no stranger to the ways in which the press and public seem to feel entitled to information about an athlete’s body. In 2009, her medical test results were leaked and discussed in detail and at length by fans and journalists who felt emboldened to pass judgment about whether she was “really a woman,” based on private medical information she never wanted shared. Semenya has, in the past few years, been quite public about her story and her biology (she recently published a memoir called The Race to be Myself), but for many years she wanted nothing to do with the press. She had no desire to discuss her body or biology. She just wanted to run.

I have been traveling around the world to report my podcast series, speaking with women like Christine Mboma, Maximila Imali, Aminatou Seyni, Evangeline Makena, Annet Negesa, and more—all of whom have been scrutinized and picked apart because of their bodies. Each time I spoke with them, I couldn’t help but think about the fervor with which journalists and some historians work to uncover the “hidden story” behind athletes like Walsh, Dillema, and Ratjen. What is gained from this kind of close reading of a person’s body, often against their wishes?

As with anything, these kinds of decisions bring tradeoffs. There can be upsides to sharing the stories of intersex athletes from the past. Knowing that intersex athletes have always competed in women’s sports is valuable. These stories offer up examples of athletes who were treated badly, banned, or misunderstood due to prejudiced ideas of what a woman is supposed to look like. It is useful to be able to draw lines from events in the past to injustices of the present. It’s one thing to be passively aware of the fact that from 1966 to 1999, every single woman who competed at the Olympics had to go through sex testing, and that some number of them were told that, actually, they weren’t really women and they had to leave. But the cruelty and unfairness of a policy like that is easier to understand when its origin can be traced back to the way athletes like Walsh, Dillema, and Ratjen have had their lives and careers flattened and scandalized by history. The vilification of Semenya, Imane Khelif, and other athletes who have been labeled as DSD is easier to critique when the historical prejudices and misunderstandings that led to such vilification are clearly seen.

A better understanding of the historical record also helps to debunk a myth sometimes used to justify sex testing: the idea that men snuck into women’s competition to win glory. That has never happened, as far as we know, at the elite level. Instead, what has happened is that women who might have variations in their biology are dehumanized, examined, and often removed from sports.

But our understanding has to go beyond the reductionist framing of “hidden secrets” and “scandals of the past.” These stories should serve to educate the public that these kinds of variations in sex biology are not nearly as rare as you might think (by some estimates, they appear in 1 to 2 percent of the population). And they should serve as a lesson in empathy, not as vessels for drama.

This is something that historians of queer culture consider deeply. The American Historical Association has a code of ethics which lists four core values: “freedom and integrity (of historians), respect (for those they study), and the careful and methodically determined and executed search for historical truth (as the result of the interactions between historians and others).” Most historians I spoke with while reporting my podcast spend a lot of time considering these questions, and how to balance the value these stories bring to the historical record with the potential wishes of the people they’re writing about.

“What purpose is this serving? What story am I telling?” asked Mary F.E. Ebeling, a professor of sociology at Drexel and the author of Afterlives of Data: Life and Debt Under Capitalist Surveillance.

“I do not think that the public is ‘owed’ anything, whether the person was famous or not,” said Elizabeth Reis, the author of Bodies in Doubt: An American History of Intersex. “I think that most would agree that being respectful to the dead should be the cornerstone of our historical ethics, and ‘respectful’ in this context would mean aiming for truthfulness and accuracy (as far as it can be ascertained).”

Amanda Lock Swarr, the author of Envisioning African Intersex, says that for her, it’s a balancing act. “I don’t think the public is owed anything or that there is one truth,” she told me by email. “And especially in the case of intersex athletes, I am most concerned with not extending the exploitation that they too often faced in life. I often think about the person as if they were alive and try to give them the same respect I would if they were in the room, reading the research themselves, even if they have passed away and the work is more historical.”

Ultimately, Reis said that “it’s up to the historian to decide if they think that there’s a compelling rationale to write about what they’ve discovered about a person.” But that decision should be considered with care and ethical consideration.

Sports fans and journalists, at least in my experience, don’t spend nearly as much time thinking about these questions of ethics. But I think we should. In telling the stories of these athletes, we have a duty to think about what we’re actually trying to say. Why does it matter that Walsh was potentially intersex? What does that story help the audience understand?

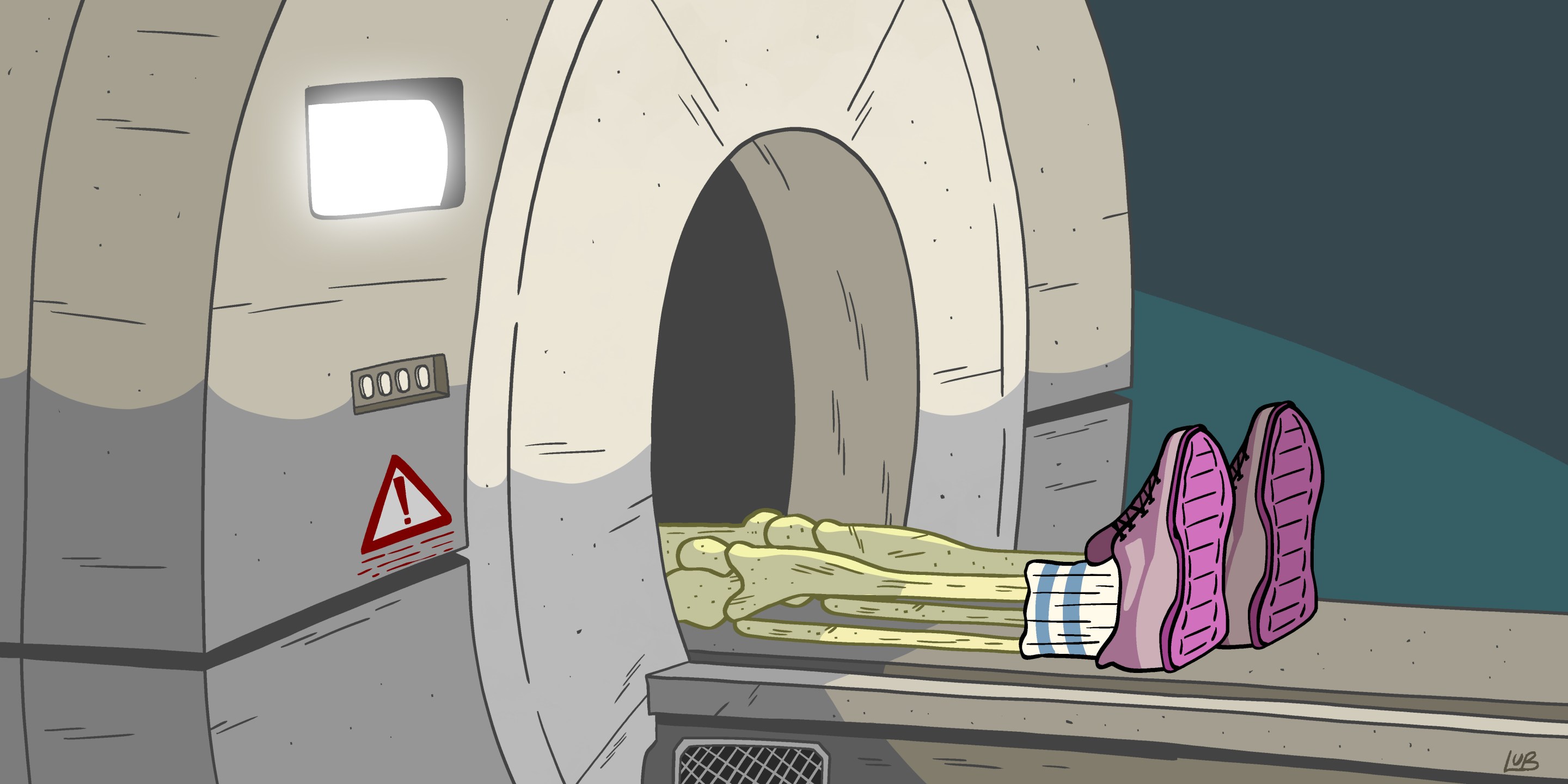

The ideal outcome of telling these stories is not simply to entertain people with a great yarn or a scandal. The goal has to be bigger than that: to open up someone’s mind to receive a more nuanced understanding of athletics and biology, so that the next time they hear about an athlete like Christine Mboma or Imane Khelif or Caster Semenya, it isn’t seen as surprising or “controversial” that their bodies exist as they do. Learning about history should be in service of providing context, of telling people that we’ve actually been here before, and ultimately of shaping a better future—one in which women can simply compete, without questions about their internal anatomy.