There’s an episode of The Simpsons where the Springfield Elementary kids play for a pee-wee football team coached by Ned Flanders. Early in the episode, Flanders has just finished assigning everyone their positions when Lisa Simpson barges onto the field, helmet in hand, demanding to know hers. “That’s right,” she says. “A girl wants to play football! How about that?” But in a delightful bit of subversion, Flanders does not blink. “Well, that's super-duper, Lisa. In fact, we've already got four girls on the team,” he tells her. Lisa, so geared up for a crusade, looks crestfallen. It is then you realize this will not be a Lisa episode, and it is then she realizes it, too. There is no tension to be resolved, nothing interesting left for her to do. She goes home.

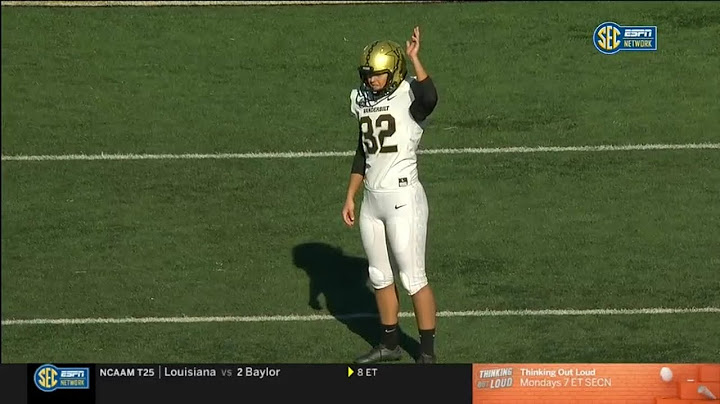

I thought of that tension, of Lisa Simpson, and what is and isn’t considered interesting last weekend, when Sarah Fuller, a goalie for the Vanderbilt women’s soccer team, became the first woman to play in a Power 5 college football game after a COVID-19 case left Vanderbilt’s entire kicking squad ineligible to play. Fuller, who nailed a designed squib kick to start the second half against Missouri on Saturday, will be on the roster again in a game against Georgia this weekend, the team announced yesterday.

One inevitable consequence of this news is that the culture warring that’s followed Fuller for the last week will only drag on. A segment of conservative media has recently taken intense interest in asking easily answerable questions about Fuller, like whether she was taking the job from a man (not evidently), and why Vanderbilt could not have scouted a kicker from its men’s soccer team (because the men’s team doesn’t exist). It says not particularly comforting things about the American psyche that a common response to the news was to imagine Fuller in all sorts of violent on-field situations. Another brand of criticism called her playing a “publicity stunt,” conflating events concocted for publicity and ones that are publicized. (Of course the Vanderbilt Athletics PR department was going to tweet about the only noteworthy thing their 0–7 football team has accomplished this season.) The claim was dismissed, anyway, by Vanderbilt’s special teams coordinator Devin Fitzsimmons, who told The Athletic’s Nicole Auerbach, “This wasn't a PR stunt. It was literally like, 'OK, what gives us the best chance to win?’ We did try out some other guys on the team that allegedly played soccer, like, when they were six. It was brutal.”

There’s a reason Lisa could muster little joy at the prospect of being the fifth woman on the football team, and it’s that she was smart enough to know that history—especially the fashionable sort of women’s history that fills illustrated stocking stuffer books about Joan of Arc and Cleopatra—reserves considerable glory for firsts and "trailblazers," and not much for anyone else. That contributes to an awfully linear understanding of progress, in which there is no stagnation or regression, and momentarily disruptive events are mistaken for catalysts of change. For all the mention of the inspirational nature of Fuller's kick—and I have no doubt young women were inspired by her talent—there was something strange about how detached and decontextualized it felt. The sports media coverage did not place her in any kind of lineage of women in football (and there have been many), nor take the opportunity to examine the barriers that make women kickers common in high school but rare in college. Fuller seemed to be considered as just a feel-good point alone in space, a thread plucked from the fabric, a clip in the highlight reel. It was not clear that Fuller's kick, an opportunity only allowed to her by some fluky circumstances and one still denied to many women who would probably be interested and capable, should be celebrated for representing some kind of dramatic institutional improvement. (Though it certainly flatters the sports world to imagine it does.)

She was a sixth-paragraph parenthetical in stories about Fuller for most of the weekend, but it's worth revisiting the case of Katie Hnida, who became the first woman to score in a Division-I college football game when she kicked for the University of New Mexico Lobos in 2003. Before transferring to New Mexico, Hnida was a walk-on at Colorado, where she was subjected to all kinds of abuse and sexual harassment at the hands of her teammates. When Hnida spoke publicly about these experiences afterward, Colorado coach Gary Barnett's answer to the press was, “It was obvious Katie was not very good. She was awful. Katie was not only a girl, she was terrible. OK? There's no other way to say it.” Have things actually gotten easier for women in football since Hnida played? There is no way of knowing, so long as "novelty" and "historic-ness" are the only frames through which we choose to look at women in sports. But it does feel genuinely encouraging that Fuller's teammates, even if they let her down by sucking so much they could not even get into field goal range, appeared sincerely happy to have her there.