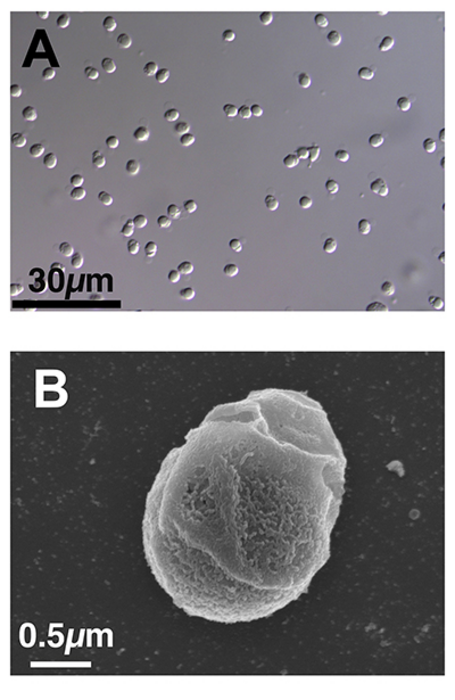

As humans, we think of sperm as swimmers. Unless something has gone wrong, sperm are valiant wrigglers, beating their tails ceaselessly to corkscrew like playful otters through fluid. But across the animal kingdom, sperm does not always have a tail with which to swim, or even move, in pursuit of an egg. What if I told you that sperm could be balls? Smooth, totally tailless balls of sperm? Balls incapable of swimming or moving of their own accord toward an egg or anything else? Balls that are released not like a flock of flapping doves but dropped, humbly inert, like a sack of potatoes?

For elephantfish in the family Mormyridae, some of which have elongated, vaguely trunk-like mouths, sperm is balls. These fish have tailless sperm that is also immotile, meaning incapable of moving on its own. (A close relative, the aba aba knifefish Gymnarchus niloticus has tailless sperm that cannot swim but can crawl like an amoeba.) Ejaculate this slothful may sound like an evolutionary mistake, making successful fertilization an act of chance and dooming a species' long term survival. Yet in their home in the rivers of Gabon, elephantfish have absolutely no problem making more elephantfish. "These fishes are incredibly abundant in their natural habitat," said Jason Gallant, an evolutionary biologist at Michigan State University. "Very often there are hundreds or thousands of them in the rivers."

The elephantfish is not only unique in the shape of its sperm. Gallant's lab studies elephantfish because they are electric. The fish dwell in waters so murky that they have evolved the ability to produce and perceive electric charges to navigate and meet up in the rivers. The elephantfish is considered a weakly electric fish—this is the official term, not a diss!—as its discharges are too weak to use for attack or defense. On the other hand, strongly electric fish like the electric eel can stun prey with their electric discharge.

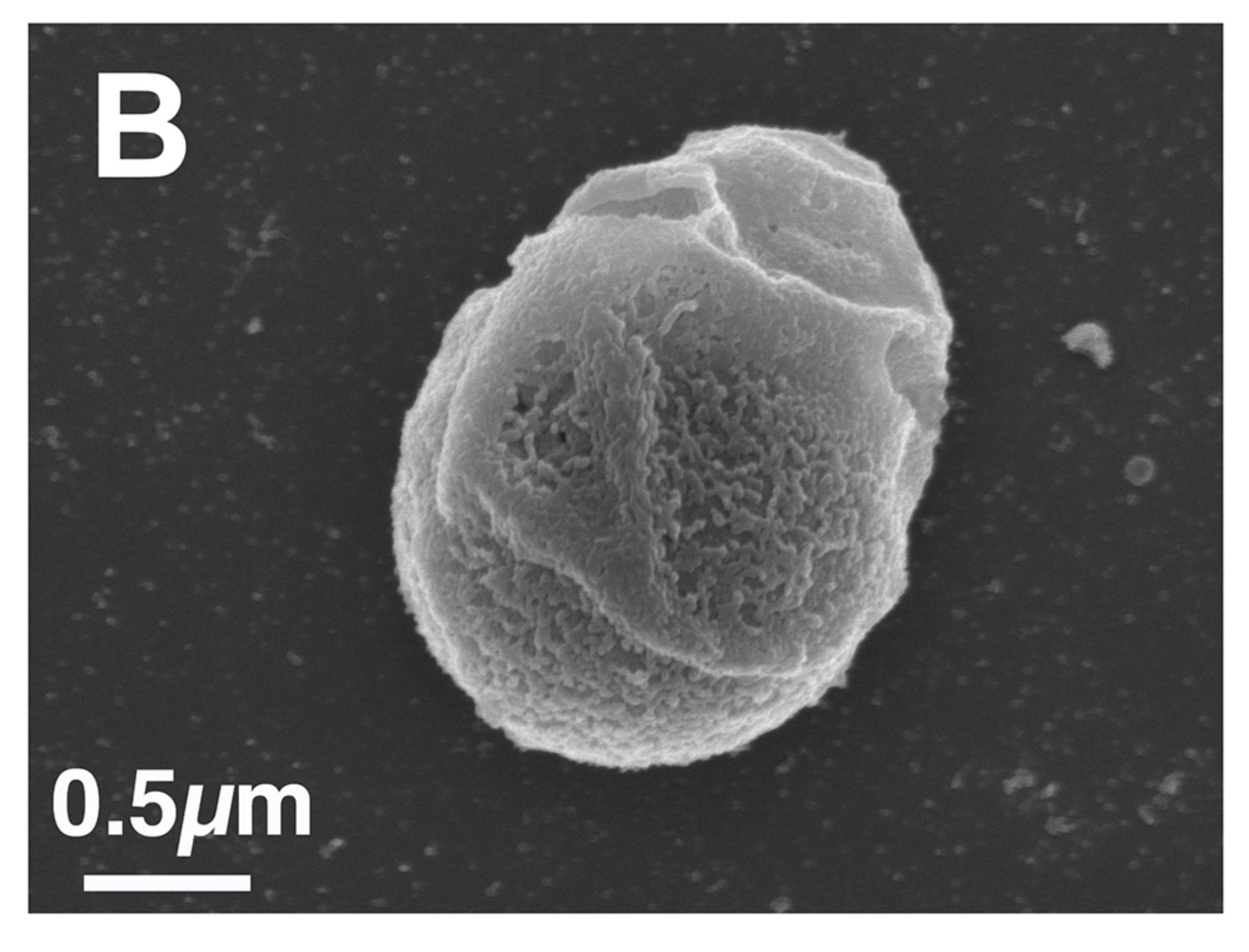

Speaking of discharge, a typical sperm, in our biased human view, is tiny. It has a head full of genetic material, a body powered by mitochondria, and a tail called a flagellum that powers the whole thing. But sperm exists along a spectrum of shape, size, and ability. The fruit fly Drosophila bifurca produces a truly giant 57 millimeter sperm cell that, when uncoiled, is more than 20 times as long as the size of an adult. The sperm of the termite Mastotermes darwiniensis has approximately 100 tails. Tailless sperm has evolved at least 36 times in the animal kingdom, in a whole bunch of worms and other invertebrates and one vertebrate—the elephantfish. It's a dubious honor but certainly a memorable one.

A few years ago, while trying to develop a gene-editing model for electric fishes on a National Science Foundation grant, Gallant was rearing elephantfish and knifefish in his lab. The knifefish were breeding happily; the elephantfish, not so much. Gallant puzzled over why this was happening. "I remember this old paper I came across when I was in grad school, that they had weird sperm or something," he said. His lab began checking the genes that had a role in forming the flagella, or tail, of a sperm, and found a big chunk of one of the responsible genes was missing in elephantfish. At last—a genetic bases for the sperm balls!

Now, Gallant and and biologist Bruce Carlson at Washington University in St. Louis have received another NSF grant to more directly study the elephantfish's tailless sperm. They hope to answer many questions: "How does the fish get away with this? What are the causes? What are the implications for their lives?" Gallant speculates that the species maybe saving energy by forgoing sperm tails. It is very energetically taxing to be electric, so elephantfish have enormous brains to power and analyze all their electric signals. And these electric signals are nearly constant during the breeding season, leaving males at an energetic deficit, Gallant hypothesizes. "It's possible. We're still working on saying for certain," he adds.

For now, researchers know one strategy that elephantfish use to give their sperm a fighting chance. "The male actually has this really cool behavior when he's spawning, akin to an erection," Gallant said. "When you stroke the anal fin of the fish, it curls up." This anal fin reflex helps researchers identify female and male fish in the field. But, like an act of aquatic origami, the fin folding creates a helpful little cup where the male can deposit his sperm and the female can deposit her egg. Researchers believe this jostling helps increase the chances the sperm finds the tiny opening on the egg through which it needs to enter. "It's kind of like shaking dice at a craps table," Gallant said.

If the rise of corgis has taught our society anything, it's that not everything needs a tail. The tailless sperm balls of the elephantfish may not be quite as smooth and spherical as elephantfish eggs, but they are beautiful in their own right. Shake away, little elephantfish! I raise my anal-fin cup to you!