Marathon running is a brutal, pointlessly painful sport that has no business being as popular as it is. Let’s be honest: 26.2 miles is simply too long. The half-marathon is the better distance in almost every respect, providing all of the benefits of endurance running at a fraction of the suffering. Everyone would be better off if 13.1 miles were called "the marathon" and 26.2 "the double marathon.” Sadly, running culture chose a different path, and as a result, tens of thousands of people put themselves through a mass orgy of misery that is also one of the most inspiring civic events in modern North American life. The label matters, because the marathon serves a single purpose; completing one gives you the ability to tell yourself and others, "I just ran a marathon." This is no small thing.

In 2011, I looked like shit and felt like shit. At the age of 28, I was a pack-a-day smoker, I had never exercised in my life, and my aspiration to be a working comedian appeared to be growing more distant by the day. I worried that I was simply incapable of accomplishing what I wanted to in life. In a fit of desperation, I signed up for the New York City Marathon, simply because I wanted to prove to myself and everyone I knew that I could do something we all thought impossible. I started running from a dead stop. I did Couch to 5K, I woke up at 5:00 a.m. to run the nine New York Road Runners races that are required to guarantee entry, and I went on nearly half a year of grueling training runs through New York City air that was the temperature and consistency of soup.

The day of the race, it took me five hours and 54 minutes to finish, slow enough by marathon standards that I was beaten by multiple 80-year-olds. But I crossed the finish line, and I didn't die. Like tens of thousands of others, I had the experience of transcending myself. In many ways, it was a turning point in my life.

A decade later, in my new home of Los Angeles, I decided to commemorate the anniversary by running the marathon again. This time around, I was 39 and had a demanding job (making a new television show called The G Word, premiering today on Netflix!), so I took a decidedly lazier approach to training, taking it easy during the week and doing progressively longer runs every other weekend. I was just trying to finish and have a good time; my only goal, insofar as I had one, was that if I could come close to my time from a decade ago, that would be pretty neat.

On the day itself, I spent the first half of the race enjoying myself: taking photos, standing in extremely long Porta Potty lines while other runners streamed past me, and hugging friends on the sidelines. But around the 16th mile, I did the math in my head and realized: If I kept up my pace, I could actually beat my time from a decade ago. Kick age in the ass and leave a size 11 Saucony Kinvara-print on Father Time's face! For the first time in my life, I started paying attention to my splits and calculating what pace I needed to maintain to stay ahead of my 28-year-old ghost runner. This meant running (or, let's be honest, run-walking) at a strenuous pace for the next two hours—but I was doing it. I was chewing up the miles. Age was just a number, etc.!

Then I reached Mile 18, and I discovered what the Los Angeles Marathon had done to its course.

Until last year, the LA Marathon famously ran from the "Stadium to the Sea," starting at Dodger Stadium, passing through downtown, Chinatown, Silver Lake, Hollywood, and Beverly Hills, before ending at the Santa Monica beach. Designing a course that truly goes from one end of Los Angeles to the other is impossible in such an immeasurably sprawling city but, if you had to choose one, this route has as good a claim as any. It also had the advantage that you were running toward, you know, the beach. What could be a better reward for your toil than the Pacific breeze on your salt-chapped face?

In 2020, the ultra-affluent enclave of Santa Monica demanded the organizers of the marathon pony up an additional fee to stage the marathon's finish line in their absurdly wealthy city. The exact amount isn't known—a city spokesperson did not reply to a request for details, and a press release from the race’s owners only vaguely mentioned “dramatically increased costs”—but it was apparently enough to spur the LA Marathon to pull out from Santa Monica entirely. Instead, they rerouted the race to end in Century City, on the Avenue of the Stars, presumably so-named because it's flanked by the talent agencies that suck cash from the Stars’ pockets.

I didn't pay much attention to all of this before the race, so it wasn't until I was actually running the marathon that I realized what they had done. Around Mile 18, I passed what appeared to be a large celebration on my left. What the fuck—is that the finish line, I thought. Soon I began passing by hundreds, then thousands of runners heading in the opposite direction, and a chilling understanding crept through me: They turned the course into an out-and-back.

I can only speak to my own experience, but compared to unidirectional or looped routes, out-and-back courses are approximately 3,000 percent more difficult to run. The reason is psychological: If you're running toward a finish line somewhere off in the distance, progress is always ahead of you, and every step is in the right direction. All you have to do is keep your legs pumping while you watch the ever-changing scenery roll by. The curse of the out-and-back, though, is that, until you reach the turnaround, you're not getting closer to the finish line: You're actually running away from it. Your mental game becomes an endless Zeno's Fucking Paradox: Every mile marker reminds you that you are only halfway to the halfway point; the next, that you are now halfway to three-quarters of the way to being halfway done. Instead of enjoying your progress, you spend the race mentally subdividing infinity. It's torture.

To compound the pain, the out-and-back portion of the course is in Century City, an ugly, treeless strip of asphalt that just so happens to be on a hill that you have to climb not once, but twice, the second climb taking place in the last goddamn mile of the race. And in a final crime against course construction, when you finally cross the finish line, instead of being greeted by the great Pacific Ocean—that vast ineffably deep primal body that humans have stared across in longing for millennia—you instead find yourself in the Westfield Mall, next to the Panda Express. As you flop down on the hostile concrete architecture and massage your aching legs, even the most ardent civic booster is forced to agree: This sucks.

Why would the LA Marathon do this? Why would it put a gun against its own thigh and pull the trigger, making the event objectively worse for 15,000-odd participants just to save a little bit of money? The answer might be found in the name splattered across every sign and singlet on race day: The McCourt Foundation.

The LA Marathon is run by the family foundation of Frank McCourt, a billionaire most famous for previously owning the Los Angeles Dodgers. The phrase "used the Dodgers as a piggybank" is such a famous cliché that it's likely to one day appear in the man's obituary. McCourt took out massive loans against the franchise to finance his lifestyle, turned the team into a bargaining chip in his multi-billion dollar divorce settlement, and generally behaved with such flagrant self-interest that Major League Baseball itself had to wrest control of it away from him. If a cabal of monopolists has to kick you out for being too greedy, it's safe to say you're a fucker.

You can kick a billionaire out of the VIP room, but that doesn't mean you can make him leave the party. Despite McCourt's pariah status in Los Angeles, his family foundation continues to control the city's single-largest sporting event. The McCourt Foundation claims to operate the marathon as a non-profit. But: Even if we were to forget the fact that family foundations are generally used by the ultra-wealthy as tax shelters to permanently hoard money and power, that the foundation's mission statement gestures vaguely in the direction of medical research without stating what it actually does, and that the only information under the "Medical Research Partnerships” section of its own website are the words "Coming Soon," the idea that the LA Marathon, as an organization, serves any purpose other than profit is rather hard to swallow.

Even the process of getting a bib for the LA Marathon requires facing a consumerist gauntlet. To get it, every participant must make a mandatory visit to the pre-race festival at Dodger Stadium, where you’re then funneled through a half-mile long tunnel full of apparel hawkers, sweaty energy-drink entrepreneurs, and predatory cell phone and cable TV reps, before finally being allowed to return to your car. It's the ultimate "Exit Through the Gift Shop,” except you haven't even entered the event yet. Being subjected to an endless series of scams is merely the price of admission.

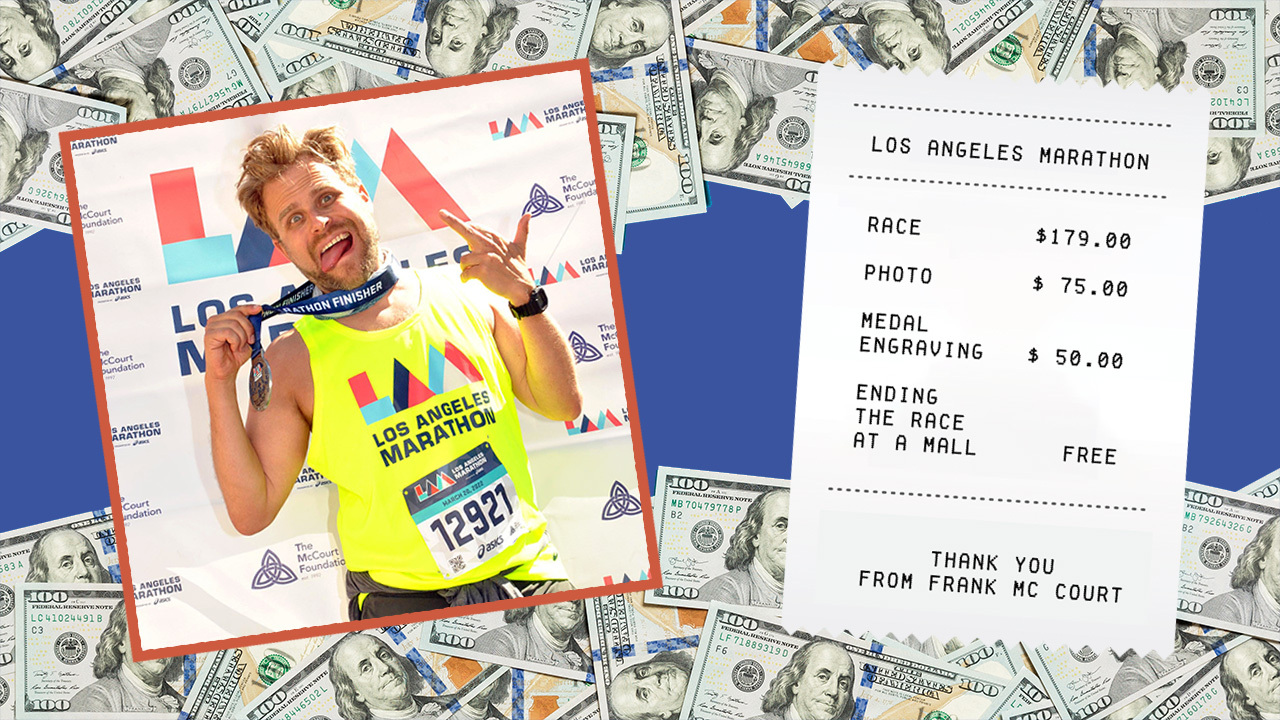

The race course itself isn't much better. It's lined with sales reps, shoving packets of gel in your face and threatening to roll out your calves with proprietary devices. The singlets worn by the thousands of public school students who run with the "Students Run LA" program are shellacked with the logos of Honda, Nike, and the McCourt Foundation itself. And when you finally cross the finish line, you find yourself in the aforementioned mall, where you can pay $50 to get your name engraved on the medal that you were just handed, and a photographer takes your photo, a copy of which will cost you $75, according to an email you receive the next day.

All of this communicates clearly that, whatever the foundation's protests to the contrary, this event exists because a lot of people are making money from it. The LA Marathon didn't miss a year because of COVID-19. The March 2020 edition of the race was held as scheduled, about a week before shutdowns began, despite the evidence pointing to global travel as the prime driver of infection and the certainty that there were positive cases already in Los Angeles. The 2021 race was pushed to November, just before a devastating surge swept through the county. The 2022 edition was held as scheduled, five months later. Quick quiz: Do you think the McCourt Foundation, the city of Los Angeles, and their corporate sponsors refused to cancel the marathon in the face of a deadly pandemic because A) It's an inspiring charity event that teaches kids the importance of blah blah blah, or B) because a hell of a lot of money was at stake? I'll let you score your own test.

So why on Earth would the LA Marathon opt to dismember its own course, turning what could be a world-class civic event into a revolting slog through a hilly office park, when all they saved was a few extra bucks? I propose that it’s the same reason a baseball owner cuts payroll instead of investing in players who could bring his team a winning record, making it beloved in the minds of its fans, and lifting the spirits of an entire city. And it’s the same reason the politicians who control the LA Metro system voted to cut bus service, when expanding public transportation for the working class would be the single most cost-effective way to expand the city's economy and achieve its climate goals. The billionaires and elected officials who run our vital institutions don't care that investments, maintenance, and improvements would benefit everyone, themselves included. Instead, they'd rather cut costs and maximize short-term profit at our expense. Why would they do anything else? They're making money, and that means they're right.

All of this ran through my mind as I trudged through the final miles of the race. At one point, I had been on pace to beat my old time by almost 15 goddamn minutes, but I was starting to feel myself slow down. I checked my watch. I was falling behind. The mile markers seemed further and further apart. Every song on my playlist felt like sawdust in my ears. By this time, I was long past running; it was a grueling effort simply to keep walking at a decent pace. After hours of sustained effort, it felt like I would be trapped on that out-and-back forever.

As any marathon runner knows, Mile 26 is the worst of them all. You should be happy! You are near the end! But you forget that this mile, unlike all others that came before it, is one-point-two miles long, and that extra distance makes it stretch on into infinity. In fact, once I passed the mile marker, I couldn't even see the finish line ahead of me. Had I miscalculated? Had the marker actually said "24," or was I hallucinating? I kept my legs moving; that was all I was capable of.

Suddenly, the entire mass of runners turned to the right. The finish line had been hiding, just out of sight around a 90-degree turn, so that it could serve no motivational value whatsoever—a final "fuck you" from the McCourt Foundation’s race constructors. I broke into a sprint across the finish line, grabbed my medal, and flopped down on the six-foot grassy median outside of a Chipotle. I checked my watch. I had beaten my previous time by four minutes. A decade older, yet a little bit faster. Self-transcendence, once again.

Around me, people were smiling, hugging, and toddling off to the Post-Race Zero-Alcohol Beer Tent Sponsored by Heineken, or crawling to the free massage station, which was inexplicably and cruelly placed at the top of two flights of stairs. I texted a friend: "How was your race?" "Awful," she replied. "The course was bullshit! I can't wait to do it again next year."

I stared at the sky, and took a selfie in the grass with my medal. Then I went to get my much deserved free Heineken Zero. Sorry, the talent-agency intern manning the booth told me: They were all out.