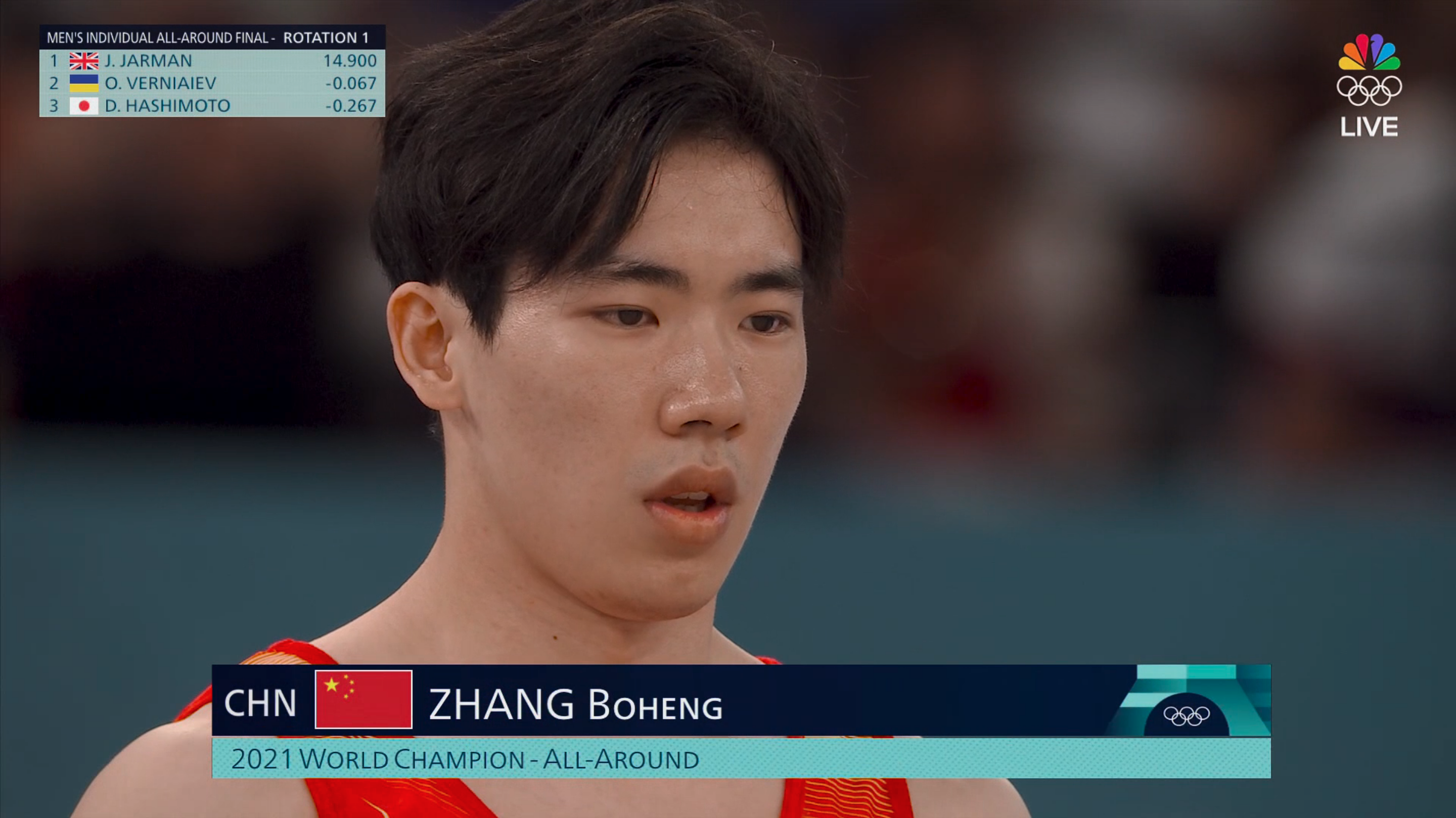

The Olympic nameplates have a style guide. Though the TV broadcasts favor small caps over lowercase letters, the general rules of capitalization are the same—the given name of the athlete is written out with standard capitalization, and the family name is in all caps. To borrow some relevant gymnastics examples: Simone BILES. Suni LEE. Stephen NEDOROSCIK. Daiki HASHIMOTO. And, of course, ZHANG Boheng.

Like any other style choice, the family name capitalization is a decision made for a reason. Viewers, unfamiliar with most athletes gracing their screen, want to know what the family name of an athlete is. What the capitalization implies is that the family name is not automatically discernible. Perhaps this is unnecessary simplification—the standard of East Asian name structure has become more common knowledge, if just because Wikipedia has a little reminder on top of most East Asian celebrities' pages: family name first, then given name. Still, there was a small press cycle when Zhou Guanyu (Olympic style: ZHOU Guanyu) came into Formula 1 in 2022, both to cover how to pronounce his name to acceptable standards, and to make sure everyone understood that Zhou was his family name, not his given name.

Which is all easy enough to internalize, except within the same sport, Yuki Tsunoda would write his name in Olympic style as Yuki TSUNODA, not TSUNODA Yuki. So here's an exception to the rule. Anecdotally speaking, it is more common for Japanese athletes to have their names written out in the Western arrangement than for Chinese athletes. There's Daiki Hashimoto above. Ichiro Suzuki was Ichiro SUZUKI—though he complicated the matter by using his first name on the back of his jersey in a league where that's very uncommon—while the whole time Yao Ming was in the NBA, he was YAO Ming. But while this is true for Daiki Hashimoto, Yuki Tsunoda, and Ichiro Suzuki, it is not true for the Japanese men's street skateboarders at the Olympics, though only in reading. Their Olympic name plates read HORIGOME Yuto and SHIRAI Sora, but if you were listening along to the commentators, you would say their names as Yuto Horigome and Sora Shirai.

This is the beautiful simplicity of the Olympic nameplate style. Even with such discrepancies, there isn't any confusion about what the family name is. You read where the caps lay, and you can make the according adjustments to what the commentators are saying, which you often need to do, jumping from event to event. The Olympics are a rare case study in the inconsistencies of translating names—how often do you get so many athletes from so many different backgrounds and disciplines listed in one competitive environment?

Even athletes competing in the same event, under the same flag can differ in how they present their names. You've probably seen the photos of Kim Ye-ji competing in the 10m air pistol event at the Olympics (the viral clips come from a different competition), but she lost that event final to her teammate, who was not using cool cyborg-looking glasses, Oh Ye-jin. While Kim's name is written on the official Olympic schedule as KIM Yeji, her teammate's is written as OH Ye Jin, splitting the given name into two words rather than one. Most Korean shooting athletes follow Kim's stylization. The only other exceptions are Lee Bo-na, who is LEE Bo Na, and Song Jong-ho, who is SONG Jong-ho.

From an external perspective, it's impossible to tell where these inconsistencies stem from. It could either be from the participating nations—is there some form of manual entry for all of the names?—the Olympic event organizers, the broadcasters, or even from the participants themselves. And then you have the media. Even though AP style, which I am beholden to, dictates a standard for handling South Korean names (family name first, given name hyphenated), various publications write Kim's name in a different style than Oh's. Why did The Athletic and the Guardian both pick Kim Yeji, but Oh Ye-jin? There is no reason in Korean, where Kim and Oh's names are 김예지 and 오예진, respectively, to favor one over the other; it could be a matter of declared personal preference, or maybe the spellings were intuited from the official Olympic spellings. No spelling or style is necessarily wrong—it's just a fault in translation.

Look at diaspora athletes. Table tennis player Dang Qiu, who was born in Germany to Chinese parents, is a simple example. His name is stylized as Dang QIU, with the family name at the end. All Chinese national athletes who have two-character given names have their given names romanized into one word in Olympic style—WANG Chuqin—except for the badminton players and only the badminton players, who style their given names in two separate words—CHEN Yu Fei. (This does imply that there is some level of event-by-event factor for name stylings; as you may imagine, the state of being a badminton player is not some base characteristic of Chinese name romanization.)

But Luxembourgish athlete Ni Xialian, who was born in China and competed for the Chinese national team 40 years ago, has her name displayed as Xia Lian NI: two words, given name first. In their article about the 61-year-old's Olympic run, the Guardian maintains the standard Chinese name ordering, but still splits Ni's given name into two words, writing her name as Ni Xia Lian. Again, it's unclear where the directive for the spelling came from; in the same article, Chinese table tennis player Sun Yingsha has her given name written as one word. Just like Ni, French table tennis athlete Yuan Jianan's name is written in Olympic style as Jia Nan YUAN, but in a sort of inverse to the skateboarding commentary, the announcer continually referred to her as Yuan Jianan.

Americans are much more accustomed to seeing the translation into English, but it goes the other way, too. Surfer Connor O'Leary recently made the transition from representing to Australia to representing Japan—his mother, Akemi Karasawa, is a former Japanese surfing champion—and in the Olympics, this transition has come with a change to the representation of his name: on both broadcasts and the official Olympic schedule, his name is written as O'LEARY Connor. The American broadcast still referred to him as Connor O'Leary, which is also how official English-language Olympics press refers to him. On Australian television, there was a conscious effort to making a switch: One Australian commentator opened with saying "Connor O'Leary" before immediately correcting himself with "O'Leary Connor." And on Connor O'Leary's own Instagram, his name is displayed as "Connor Oleary."

Non-English names are charged objects in an English-speaking world. You switch it out at a coffeeshop to something easier, but maybe you shouldn't; you make compromises on pronunciation, but maybe you shouldn't. These are all discourses that have been repeatedly rehashed, and they all tend to operate from a sense that there is a correct way of going about these things, both as people selecting how they want to be referred to, and for the people learning how to refer to someone. Without knowing why the various Olympic inconsistencies exist, maybe both the lack of a universal standard—not enough consistency!—and the presence of smaller patterns—what if the Chinese badminton players don't want their given names to be spelled out in two words?—are due to organizational oversight rather than general ambivalence.

But take the names as they're given to you, and the concoction of inconsistencies that has resulted from these Olympic processes has its own beauty. Translate any name, and you wind up with at least two. The keepers of the Olympic style guide seem to understand that knowing all the rules won't save you. Which is the family name? How is the given name spelled? How is it punctuated? In the end, there is only one best practice: Ask, and give someone the opportunity to reveal something about themselves. Is that not, at its core, what a name does to begin with?