It was a sequence that perfectly captured the Pittsburgh Steelers’ desultory first-round playoff loss to the Baltimore Ravens on Saturday night, and also the desultory, mediocre reality that has surrounded the Steelers for a decade now. It happened early in the second quarter, with the Ravens leading 7-0 and the Steelers facing a third-and-2 from their own 28. Russell Wilson flipped a pass toward the right flat to tight end Pat Freiermuth. Just after the 6-foot-5, 258-pound Freiermuth caught the ball, Ravens safety Ar’Darius Washington—who stands all of 5-8, 180—came smashing into him. Washington proved to be no fly on Freiermuth’s windshield. He quickly brought Freiermuth to the ground just short of the sticks.

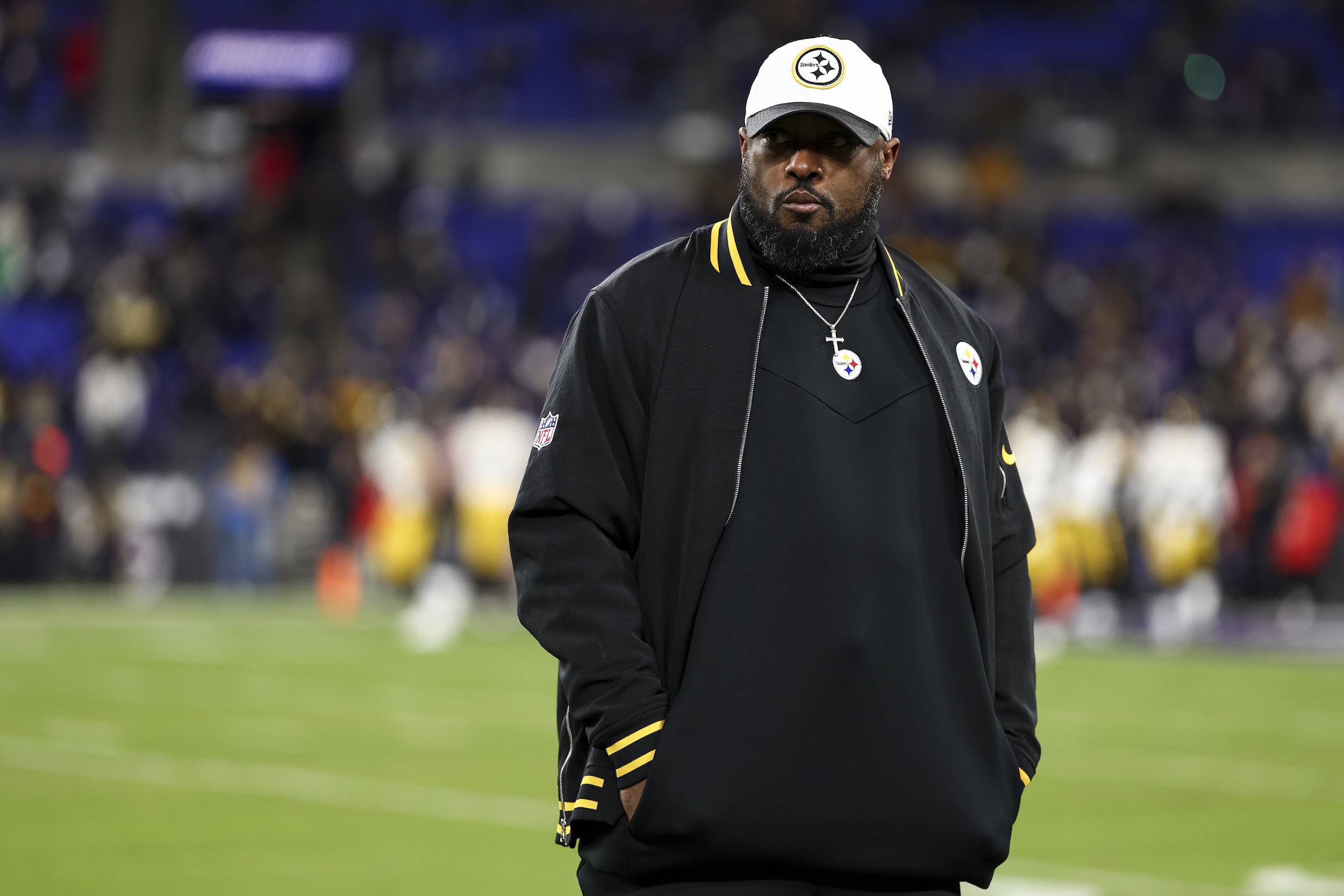

Rather than risk failure on fourth-and-1, Steelers head coach Mike Tomlin decided to punt. It goes without saying that this was cowardice, even though it was the Steelers’ inability to gain one yard on back-to-back plays that contributed to the previous week’s loss to the Bengals. ”We have to be able to make routine plays routinely,” Tomlin would later say.

What happened next completes the scene. After getting the ball back, the Ravens methodically marched 85 yards in 13 plays, devouring 7:56 of the game clock and sapping whatever will the Steelers might have had as they limped toward a fifth consecutive defeat to end a season they had started 10-3. It would prove to be just one of four Ravens touchdown drives on the night that spanned at least 70 yards. Baltimore would finish with 29 first downs and 464 total yards, including 299 on the ground. Only Lamar Jackson taking a knee at the end prevented it from being an even 300.

“You’re in the postseason, you’re getting dominated. I don’t see any fight, I don’t see any pushback,” analyst Kirk Herbstreit said on the game broadcast as the Steelers were about to begin their next offensive possession. “It’s one thing to lose Xs and Os against a really talented offense, but where the hell is the fight? This is the Pittsburgh Steelers! There’s nothing.”

This is the Pittsburgh Steelers! Herbstreit, with genuine surprise in his voice, was expressing the widely understood perception of the Steelers as a model of stability and continuity. They’ve been known for controlling the ball and playing tough defense since the Nixon Administration. Under Chuck Noll, Bill Cowher, and now Tomlin, the Steelers always seem to be in contention—a difficult thing to do consistently in a salary-capped league with a constant shortage of elite players at the sport’s most important position.

Since 2007, his first season in Pittsburgh, Tomlin’s .630 winning percentage has been eclipsed only by the Patriots and Packers. He’s reached the postseason 12 times in 18 seasons. He’s won two AFC Championships and one Super Bowl. He’s never had a losing season. Fans of, say, the Jets, Raiders, or Bears would eagerly chew broken glass to have him as their coach. He’s legitimately one of the all-time greats.

But the Steelers have been getting mollywhopped like this in the playoffs for years now! There’s nothing surprising about it at all! Every single Steelers fan on the planet knew this team was pedaling a unicycle backward down an unlit street into a manhole. It’s remarkable that anyone who isn’t a dipshit Yinzer jagoff didn’t see it that way too.

Fans of the Jets, Raiders, and Bears, please stop spitting shards of glass at me. I know that, as a Steelers fan, I’ve been spoiled. But it’s been a long time, and every season keeps ending the same, punchless way. Tomlin’s Steelers have now had three-game losing streaks after Thanksgiving five times in the last seven seasons, and six straight playoff losses over the last nine years.

I want to say this carefully, since there is a sizable number of paste-eating nimrods in Western Pennsylvania who have always seized upon any opportunity to smear Tomlin as some kind of Rooney-branded DEI hire, but here goes: In the 14 years since Tomlin’s Steelers lost Super Bowl 45, they’ve won a lot of games while simultaneously getting humiliated by the NFL’s true title contenders—in the regular season and postseason alike. He’s Mike McCarthy except he looks cool in sunglasses.

In fact, since McCarthy’s Packers beat Tomlin’s Steelers in Super Bowl 45, McCarthy has twice as many playoff wins. Tomlin is 3-9 in the playoffs in that stretch—a run that began with a Tim Tebow walkoff, by the way—but that still hasn’t stopped someone, somewhere from declaring this year “Tomlin’s most impressive job” or his “masterpiece,” or that that year or some other year or maybe that one or hell even that one as Tomlin’s best. “The standard is the standard,” as Tomlin likes to say. Mediocrity is now the standard, I guess.

Let’s start with the wins. Of Tomlin’s three playoff victories since 2011, one came against a Bengals team quarterbacked by A.J. McCarron, a game decided by Vontaze Burfict and Pacman Jones losing their minds and gifting the Steelers 30 yards of penalties in the waning seconds to set up the game-winning field goal. Another came against the Adam Gase Dolphins in 17-degree weather, with Matt Moore starting at quarterback. The third was against the Alex Smith Chiefs, a game Andy Reid reacted to by trading up to draft Patrick Mahomes the following spring. That’s it. That’s the three.

Saturday’s loss was their sixth in a row in the playoffs. Only Marvin Lewis (seven) has lost more postseason games in succession. As Herbstreit said, there’s no shame in losing, especially to good teams. But Tomlin’s Steelers have shown no fight or pushback in any of these six games. I mean, look at this load of crap:

2016 AFC Championship: Patriots 36, Steelers 17

2017 AFC divisional round: Jaguars 45, Steelers 42

2020 AFC wild card: Browns 48, Steelers 37

2021 AFC wild card: Chiefs 42, Steelers 21

2023 AFC wild card: Bills 31, Steelers 17

2024 AFC wild card: Ravens 28, Steelers 14

Those are losses to Tom Brady, Patrick Mahomes, Josh Allen, and Lamar Jackson, yes, but also to Blake Bortles and Baker Mayfield—and not one of them was remotely close, right from the start. The Steelers trailed the Patriots 33-9. They trailed the Jags 21-0 at home. They trailed the Browns 28-0 in the first quarter at home. They trailed the Chiefs 35-7. They trailed the Bills 21-0. They trailed the Ravens 21-0. In all six games combined, they were outscored 73-0 in the first quarter. Getting to the playoffs is an accomplishment, but it doesn’t amount to much if you don’t bother to show up.

The Steelers' defense in their 6-game playoff losing streak:• 38.3 PPG allowed• 418.2 yards per game allowed• 6.3 yards per play allowed• 155.3 rushing yards per game allowed• 76.9% red zone efficiency• 8 total sacks• 2 total takeaways• 1 interceptionAwful.

— Daniel Valente 🏈 (@statsguydaniel.bsky.social) 2025-01-12T18:35:42.647Z

To go further: The Steelers allowed those six playoff opponents to convert 57.1 percent of their third downs. Since the merger, only this year’s Panthers and the 2020 Titans have allowed opponents to convert more than half of their third downs across an entire season. If you bring up small sample sizes, I’m going to respond with a vigorous wanking motion.

The same largely holds true when it comes to the performance of Tomlin’s defenses against elite quarterbacks, in both the regular season and postseason. Yes, they’ve had their share of successes against Jackson and Joe Burrow, but they’ve mostly been dog-walked by everyone else. Via Stathead:

After the 2016 AFC title game, I wrote a piece for The Old Site about how Brady owned the Steelers. It included clips of Julian Edelman and Chris Hogan galloping freely through a soft zone to combine for 17 catches on 22 targets for 298 yards and three TDs. Against great teams, not much has changed. The Steelers can never seem to stop a slot receiver or tight end who simply turns around, or a quick slant, or anyone streaking across the middle or up the seam. In a nutshell, it’s been a lot of this, and this.

This is why the argument that Tomlin and the Steelers simply need a franchise quarterback to snap out of their predicament rings hollow, even though they certainly need to make an upgrade this offseason. They had a Hall of Fame QB for years in Ben Roethlisberger, and a case can be made that they wasted his best, high-volume seasons. (From the abstract of the 2015 Football Outsiders Almanac: “Can a 33-year-old Ben Roethlisberger continue to carry a defense in transition?” And from the 2019 Almanac: “One way of looking at the 2018 Steelers is to realize that … Roethlisberger was, at age 36, a steady hand that kept the ship pointed towards the playoffs until the final Sunday of the season.”) In fact, from 2011 through 2018—the year after the Steelers’ last Super Bowl appearance through Roethlisberger’s last full season before his elbow fell off, a stretch that largely aligned with the Killer Bs era that included Antonio Brown and Le’Veon Bell— DVOA ranks show that Roethlisberger and the offense consistently outperformed the defense, the pass defense especially.

The 2017 team was Tomlin’s best since 2010, and losing triple-threat linebacker Ryan Shazier to a career-ending injury late in that season was a huge blow. The Steelers missed the playoffs in 2018 (the year Bell pointlessly held out) after starting the season 7-2-1 because their defense blew fourth-quarter leads that Roethlisberger and the offense had given them three times in a span of four December games. (No, I’m still not over it.) In 2019, the year Tomlin won eight games with Mason Rudolph and Duck Hodges, he still managed to lose to the Patriots 33-3 with a fully healthy Roethlisberger. It’s worth noting that the Steelers used first-round picks on defensive players nine times in the 10 drafts between 2011 and 2020, if you count the trade for safety Minkah Fitzpatrick that essentially swapped their 2020 first-rounder to acquire him.

The conventional wisdom that Tomlin is an exceptional defensive coach mirrors Tomlin’s approach to defense in recent seasons: It’s heavily reliant on the splash plays that generate turnovers that make for thrilling clips on highlight shows or social media. But it’s also an unsustainable approach that largely requires TJ Watt, Alex Highsmith, or Nick Herbig to play heroball by getting to the quarterback out of a conventional four-man rush. Toward the end of this season, as the Steelers played better teams that cooked up ways to chip or double Watt, Tomlin never adjusted. No moving Watt around, no varied fronts, no exotic blitzes. (Watt is a four-time All-Pro who’s led the league in sacks three times. He literally registered nothing on the stat sheet in the Steelers’ last two games.) Just a risk-averse effort to prevent big plays even though he’s had the highest-paid defense in the league for three years in a row.

Tomlin’s biggest weakness may be in his selection of assistant coaches, particularly his offensive and defensive coordinators. When he took over, he wisely kept Bruce Arians (whom he promoted to OC) and Dick LeBeau as holdovers from Cowher’s staff. Arians was run off after the 2011 season (reportedly at management’s insistence) because his “no-risk it, no biscuit” style was going to get Roethlisberger killed. Arians’s replacement, Todd Haley, coordinated some terrific offenses that kept Roethlisberger upright through 2017 by incorporating more quick throws, but Haley was an asshole. LeBeau stepped aside after 2014, which (as the defensive DVOA numbers indicate) coincided with Troy Polamalu’s retirement and the general aging out of the defensive core that had once upon a time reached three Super Bowl in six seasons.

Since then? A motley collection of jabronis who might as well have been Tomlin’s drinking buddies or bowling friends: Keith Butler and now Teryl Austin to run the defense. On offense, it’s been Randy Fichtner, Matt Canada, and now Arthur Smith. For a while this season, Smith seemed like a breath of fresh air after the lingering fart cloud of Canada’s offenses, which mainly involved having receivers sprint a few yards past the line of scrimmage before turning around, punctuated by useless jet sweeps. After getting Justin Fields to use his mobility but otherwise play it safe before wringing several weeks of solid, play-action–heavy games from Russ, Smith’s playbook included lots of “Let’s keep running into loaded boxes on early downs” and “We’re moving the ball, let’s pitch it to Cordarrelle Patterson here” and “Let’s have George Pickens only run routes up the sideline and pray for a flag” and “What is the middle of the field and this sorcery people keep calling ‘a crossing route?’” After a Week 15 loss at the Eagles that proved to be the beginning of the Steelers’ season-ending freefall, Smith likened his offense to “an old pickup truck,” joking, “We’ve got to get some jumper cables or whatever we got to do. I’m not a mechanic; maybe somebody around here is.” It never seemed to occur to him that he’s supposed to be the mechanic in that analogy.

I don’t want this to be pure pile-on, but a realistic appraisal of Tomlin’s strengths and weaknesses. And he clearly has a lot of strengths. He belongs in the Hall of Fame just for wringing nine incredibly productive years out of Brown; Brown’s last game as a Steeler, literally days before Tomlin finally iced him out for good, might have been the finest performance of his career. Tomlin is a master motivator and straight-talker who sets clear expectations. He is beloved by his players in no small part because he can straddle that line of being demanding while treating people with dignity and respect. He says all the right things and can be disarmingly funny. He’s decisive, as his switch to Wilson this season proved. And, yeah, he’s won a lot of games.

The obvious comparison to make is to Andy Reid and the final years of Reid’s tenure with the Eagles, which similarly was a futile effort to plug holes on a sinking ship. But Reid was always a tinkerer and an innovator who could see where the game was headed. He understood the greater efficiencies of the passing game long before it was something Mina Kimes could explain to a general audience. He won a playoff game with Jeff Garcia and got back to the NFC title game with late-stage Donovan McNabb. The rule changes of the early 2010s and widespread embrace of quantitative approaches eventually vindicated Reid’s thinking. His ability to see Patrick Mahomes as the ideal vessel for his vision now speaks for itself. Tomlin, however, has no schematic hallmark to leave as his legacy.

The better coaching comp is either McCarthy, Seahawks-era Pete Carroll, or Marty Schottenheimer. McCarthy and Carroll, like Tomlin, won a Super Bowl early in their tenures with a terrific QB and an outstanding defense. Carroll and Tomlin each got back there again and came up short. Carroll then went 3-6 in the playoffs in his last nine seasons, with just one postseason victory in his last seven campaigns.

Schottenheimer never got to a Super Bowl, let alone won one, but he stubbornly never wavered from wanting to establish a ball-control style that defeated teams defensively, even though it was always a difficult way to succeed in the postseason. Tomlin has openly said in recent years he wants to win the same way, like it or not. Schottenheimer last coached in the NFL in 2006, long before the modern NFL passing revolution really took flight. He also lost his last six playoff games.

The continuity that the Steelers prize so highly has given way to complacency. A team built to regularly beat the Titans 16-13 and win nine or 10 games, then wilt in the postseason, is apparently good enough in Pittsburgh.

The Steelers don’t need to tank to find their next quarterback. Even Tomlin pointed out during his season-ending press conference this week that two of the teams still alive this weekend—the Eagles and Ravens—didn’t get there by recklessly tumbling to the top of the draft. Neither did the Chiefs or the Bills, for that matter; they both made aggressive trades to move up from the bottom-third of the order to grab their man.

As correct as Tomlin was, his comments inadvertently revealed a blind spot in the Steelers’ organizational thinking. The Eagles, Ravens, Bills, and Chiefs are all enjoying sustained success because they had a vision and pursued it. Reid-Mahomes is obvious, but the Eagles drafted Jalen Hurts when Carson Wentz was still a capable QB, even as there were internal indications that something wasn’t right. After losing both coordinators and collapsing at the end of last season, the Eagles pivoted and immediately brought in two of the best coordinators in the game, plus Saquon Barkley. The Bills quickly elevated their baseline in Sean McDermott’s first season and took a chance that they could fix Josh Allen’s accuracy issues by providing him with every bit of support imaginable. The Ravens didn’t wait for Joe Flacco to go away before drafting Jackson; they then quickly recalibrated the offense to suit Jackson’s skillset, and then changed coordinators when they realized Jackson had even more potential waiting to be tapped. Also, Derrick Henry.

The Steelers let Roethlisberger hang around until his throws needed a ride to reach the line of scrimmage, then looked next door to draft Kenny Pickett when no one else thought that highly of him, then doubled down on the Pickett-Canada pairing after winning seven of their last nine to close out Pickett’s rookie year. Never mind that the only team they beat in that stretch to finish with a winning record was the Ravens—in a game Jackson didn’t play.

A year ago, after another lackluster playoff showing, this was owner Art Rooney II on the state of the Steelers:

“I think there's an urgency. Everybody. Myself, Mike, guys who have been on the team for a while, T.J. [Watt], Cam [Heyward], everybody. We've had enough of this. It's time to get some wins. It's time to take these next steps. So, yeah, I think there's some urgency here, for sure … There's a resolve there and a determination there … Getting a little impatient. We need to see the kind of improvement we all want to see. Mike believes that as firmly as anybody else in the building.”

The franchise now heads into 2025 with no obvious path forward at quarterback, a defense that’s getting old, and Mike Tomlin saying things like this on Tuesday, once it was clear he’d be back: “I have a feeling a lot of things are going to change around here.” When is too early to make changes? Three days before, with the Steelers trailing by just two scores, the Ravens were in the midst of running off more than 12 minutes of the fourth quarter across two possessions. Until after the two-minute warning, Tomlin didn’t bother to use a timeout. He was content to let everything play itself out.