As the dog teams competing in the 2014 Yukon Quest rested at the race’s halfway point in Dawson City, I drove my Jeep Grand Cherokee out onto the frozen Yukon River. In Dawson, the main townsite sits on one side of the water, but the teams take their mandatory midpoint layover in a public campground on the other. For many years, an ice bridge has been built to connect the two sides—the main town and its more remote west-side suburbs—robust enough for even heavy vehicle traffic. During my coverage of the 2012 and 2013 Quests, I had always driven onto the ice bridge from the sloping boat ramp where a ferry docks in summer. That night in 2014, I did the same. It was very dark, and very, very cold.

I’d befriended a photographer from New York who was in town to cover the race, and she was in my passenger seat as I rolled us out onto the ice. We were partway across when I spotted an irregularity, a patch of darkness that resisted the light of my headlights. There was, I realized, open water lurking not all that far ahead of me. I tried not to panic, tried not to let on that we were both possibly about to die. Holding my breath, I put the Jeep into reverse, and eased back along my own tire tracks until we were on solid ground again. The next day, I learned that the bridge had been rerouted to cross farther upriver.

More than a decade later, that photographer and I are still friends, and we can laugh about the time I nearly drove us both into a slushy, premature grave. But Dawson City’s ice bridge has only gotten less dependable in the years since. And the Yukon Quest? It’s changed so much that it has hardly anything in common with earlier iterations, except the name. It doesn’t even run along the frozen river. The ice just isn’t reliable enough anymore.

Born in 1984, the Yukon Quest was the Iditarod’s younger, scrappier rival: the only other thousand-miler, with less fame, fewer big-ticket sponsors, and fewer checkpoints along its rugged route.

There are lots of metrics by which to compare them. The Quest takes place in the first half of February, while the Iditarod runs in the first half of March—when mushers enjoy far more daylight and warmer temperatures, if they're lucky. On the other hand, unlike the Iditarod, the Quest doesn’t run across sea ice and through polar bear territory; in theory, the grizzlies along the Quest trail should all be sound asleep. And the Iditarod takes place entirely in Alaska, while the Quest was always a cross-border affair.

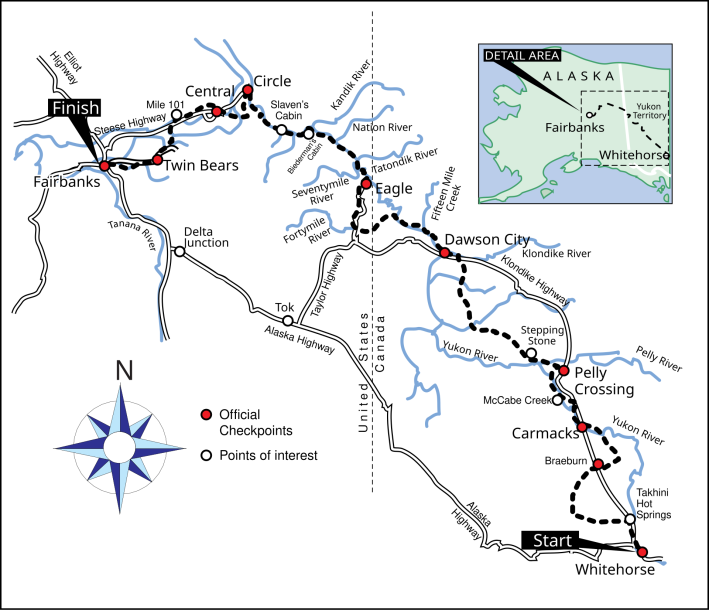

It ran from Fairbanks, Alaska, to Whitehorse, Yukon, in its inaugural year, from Whitehorse to Fairbanks in its second, and so on, the route remaining largely the same but the direction reversing. According to John Firth, a Yukon sports historian and author who covered the first Quest as a journalist before later joining the race’s board, it was named not for the Yukon Territory but for the river that provided much of its route.

While the Iditarod honors the serum run to Nome, the Yukon Quest was a homage to the mail runs—postal deliveries by long-distance dogsled, a practice that endured in some places until 1963. “The old trails that they were following were the old dogsled mail routes between the communities,” Firth said. “And a lot of that was on the river, because it was the easiest transit.”

In the time before ubiquitous passenger air service and actual highways, the rivers, whether in their liquid or solid seasons, were the “highways of the North”—and the Yukon River, about 2,000 miles long, was the biggest of them all. It rises on the Yukon’s southern border with British Columbia, and picks up speed and size as it runs from Whitehorse north and west to Dawson City and its Klondike goldfields. The river keeps rolling northwest after it crosses the border into Alaska, running through remote communities like Eagle and Circle City, and reaches its northern apex around Fort Yukon before turning gradually south, cutting down and across the entire width of Alaska before it flows into the Bering Sea.

For its first three and a half decades, the Yukon Quest’s route shadowed the river for much of its distance. The race map was adjusted over time: For instance, according to Firth, Lake Laberge, upon whose marge Sam McGee was cremated in the Robert Service poem, was swapped out in 1995 for a forested overland segment. But the river was always the heart of the route.

When I think of the race, I think of the sight of a distant dog team, looking like nothing more than a low set of shadows running below the tall, sandy cliffs that hem in the river downstream of Whitehorse. Or the steam rising off the frost-covered bodies of the dogs as they trot into a rest stop, pink tongues dangling. As spectators, we mostly saw the mushers coming and going from checkpoints where the trail was relatively smooth, and they’d emerge briefly onto land for a hot meal and a rest. What we couldn’t see as much of were the hardships the river imposed: the mazes of jumble ice that forced them to step off their runners and pick their way through, lifting and hauling their sleds while the dogs pulled. Or the patches of overflow, free-flowing water that can seep on top of solid ice, soaking a team’s feet or even plunging all the dogs and their musher into waist-deep water, or worse. The river was a highway, but it was also the source of many of the race’s hazards.

The first major change came in February 2021, when the race was canceled due to the pandemic. The Quest had always been jointly governed in a sometimes uneasy partnership between two separate organizations, one on each side of the international border, and in 2022, with crossings still complicated by pandemic regulations, the two sides decided to run four shorter races: two in Alaska, and two in the Yukon. But a few months later, the two Quest organizations announced a breakup, apparently due to a disagreement about mandatory rest times for the teams.

Even as separate, shortened events continued to run on either side of the border, fans of the Quest still hoped the two organizations would find a way to reunite, and restore the old thousand-mile race. Instead, after the 2024 races, the Yukon organization announced a radical route change for 2025: one that would take the race off the Yukon River entirely.

Two weeks ago the Yukon Quest (Yukon edition) began, for the first time, in the small community of Teslin, a couple hours southeast of Whitehorse. The racers followed frozen Teslin Lake for a short stretch before crossing the Alaska Highway and turning north up the seasonal South Canol Road, which has been closed to vehicle traffic apart from snowmobiles since the fall. Teams ran up the length of the Canol to the town of Ross River, and added a bit more distance on North Canol, an even more remote seasonal road than South Canol, before reversing direction. The 450-mile race finished back in Teslin.

On the route change, the Yukon-side Yukon Quest was clear: They had abandoned the river route that had always been at the core of their race, the river for which the event was named, because of “Mother Nature and climate change.”

Benoit Turcotte, a researcher at Yukon University, specializes in studying river ice. As he explained it, we’re not in imminent danger of the Yukon River becoming entirely liquid, year-round. “Yukon will keep warming,” he said, but “rivers keep freezing even in a much warmer climate. … You can just expect slight changes in freeze-up patterns and slight changes in weather patterns, [but] that can make a big difference.”

A lot of different elements play into it, and ambient air temperature is just one piece of the puzzle. Wind can be a factor, or early snowfall that blankets the ground and insulates it from the cold. Small changes in every little tributary can contribute to larger changes on the main body of a river, not just in terms of the volume of water moving through the system, but in the ways and places sediments settle, which in turn can alter where the first ice tends to snag and collect, eventually forming a pileup that becomes solid. In Dawson City, where Turcotte works to understand the patterns that forge or undermine the ice bridge in any given year, the merging of the Klondike River into the larger Yukon River seems to play a key role.

Lakes can play spoiler for river ice, too. “In a river, if you stick a thermometer in the water, in winter, the water temperature will essentially be at 0.0 [degrees Celsius],” or just on the cusp of the freezing point of water, said Turcotte. That’s because the churn of the river keeps the temperature fairly even throughout. “But in a lake, where there’s no mixing, the bottom of the lake is at 4 degrees Celsius. That’s a physical property of water, and you cannot change it.”

That means that while on the lake’s surface ice might form sooner and more easily than on a tumbling river, lakes are also heat sinks. Take Lake Laberge (or Tàa'an Män, to use its Southern Tutchone name, in use long before Sam McGee came along) as an example. The lake, 30 miles long and 20-odd miles downstream from Whitehorse, “is sending warmer water, all winter, downstream. And that slows the process of freeze-up quite a bit.”

Turcotte likened freeze-up to a race between the Earth’s store of heat and the air’s icy potential: ice formation wins more easily when temperatures drop further, faster, and for longer. “So it’s a constant battle.” A deep cold snap early on in a season can help the ice form quickly, but a milder winter, like the one we’ve had this year—and in more years than not, recently, it seems—means the heat sometimes wins the race.

“If you have a patch of open water, it doesn’t matter if it’s one kilometer long or 10 kilometers long,” Turcotte said. “Small changes do create those barriers.”

As I write this, large stretches of the Yukon River are still covered in navigable ice. But the patterns that have been known for generations here—for centuries among Yukon First Nations people—are shifting and becoming less predictable. And when you’re traveling over ice in temperatures that routinely reach minus-40, uncertainty is something you want less of.

This year, as the Yukon Quest unfurled along its new route, I’ve been grieving the river’s absence. It’s not just about the changes to the Quest itself, though it seems to me like a heavy omen to have a wilderness race relocated to a closed highway because of climate change. The local unit of the Canadian Rangers army reservists has always built and marked the trail on the Canadian side of the race, and the result was a piece of winter infrastructure that anyone in the region could enjoy.

The opening mile of the Quest trail was where I test-drove my brand-new fat bike, a 35th birthday present to myself, pedaling along the bare river ice and marveling at the tires’ grip. The next year, in 2018, I attempted the Yukon Arctic Ultra, a foot/bike/ski race that uses the Quest trail, its racers generally following a day after the dogs depart. I spent a gloriously cold, sunny afternoon trekking downriver, pulling a 40-pound sled loaded with survival gear, and thinking about how delightful it was to be walking on the surface of a river I had paddled down so many times.

Other memories are less firmly tied to a specific year or location. How many times, during the half-dozen years that I covered the Quest and the Ultra as a reporter, did I walk out onto a stretch of frozen river on a dark night and look up at the stars, or see the Aurora Borealis swirling? How many times did I hear the absolute silence of the river broken by the panting of a dog team, harnesses jingling, their musher’s headlamp slowly growing brighter as they drew near?

It's not that the new race route isn’t hard. South Canol Road is rippling with hills, although the new trail is certainly less technical than the old one. And it’s not that there aren’t other ways to find challenge and beauty and stillness in the Yukon winter; there are plenty. But there was something special about that frozen river, and knowing that traveling along it is becoming less viable every year feels like a real loss to me.

These little losses aren’t anything like the big ones: the wildfires and floods sweeping through entire towns and cities, the air becoming unbreathable, the ocean choking with microplastics. But we lose something nonetheless. It’s been said that climate change is almost too big a problem to wrap our little plastic-riddled brains around. Maybe, then, it’s the small losses that can make it comprehensible. Maybe it’s the small griefs that will help us change.