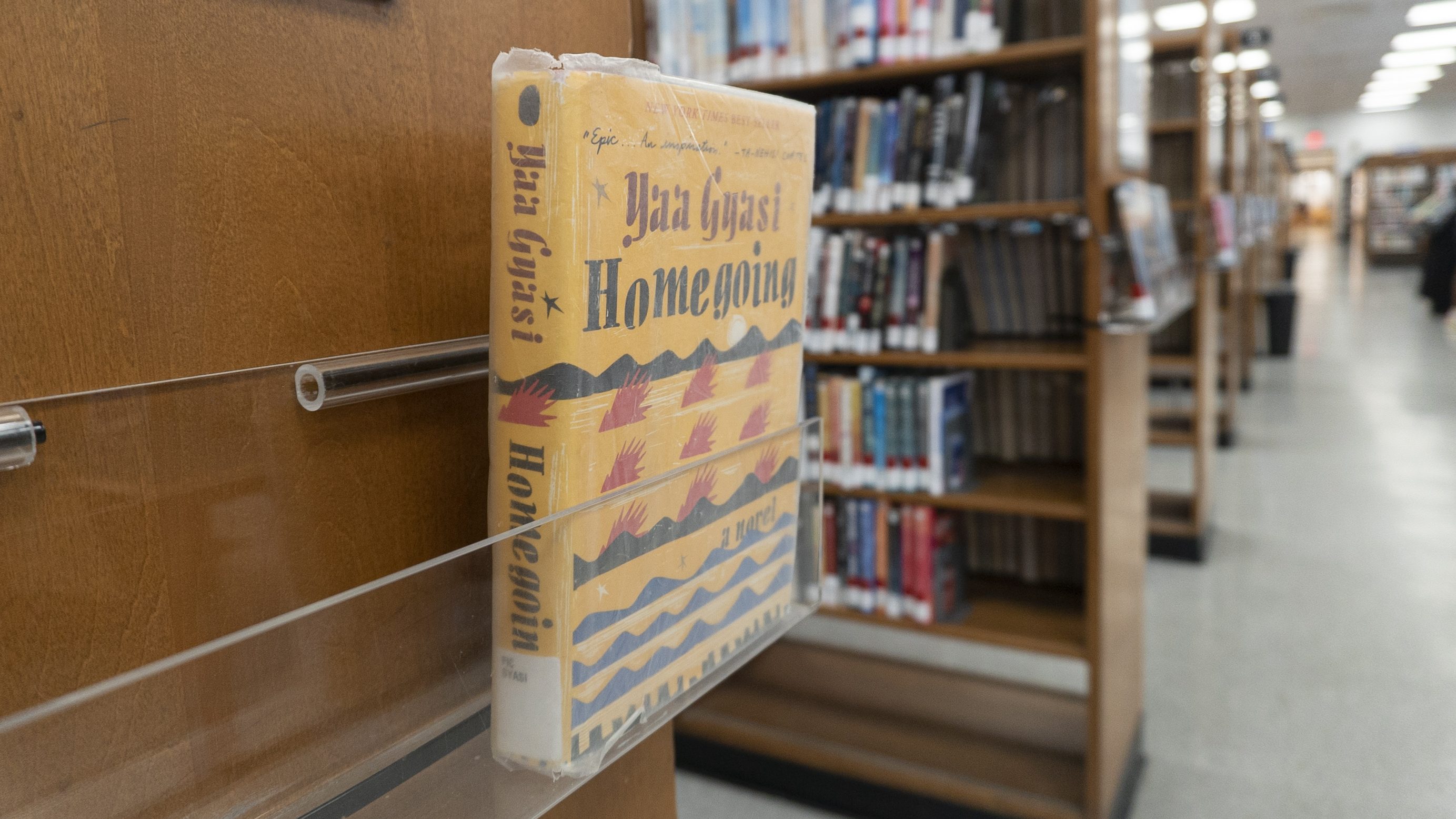

Meghana Nakkanti really loved the book Homegoing. The 18-year-old high school student in Nixa, Mo., loved how author Yaa Gyasi's work of historical fiction, following the descendants of one Ghanaian woman across multiple families and two centuries in both Ghana and the United States, delved into intergenerational trauma.

But Homegoing was also one of more than a dozen books that parents at Nakkanti’s school wanted to ban. She found this not just odd, but also extremely disconcerting. So, she and her fellow students mobilized.

“We showed up to school board meetings, we spoke at those meetings, we tried to have a presence in school. We discussed it with students, and the overwhelming consensus was that the book should stay in the library,” Nakkanti said. “Because ultimately, it's about choice. And so we all kind of banded together to help make sure that we could at least try to keep books in our library. But you know, it's been kind of a difficult road.”

Students like Nakkanti are part of a generation whose personal lives—from the expression of their gender through their bathroom choices to the literature they want to read—have increasingly become a vehicle for politicians and other hyper-partisan adults to grandstand about their own values. In response, like many teens before her—whether it be the March for our Lives students or the climate change movement started by Greta Thunberg—Nakkanti has been pushing for collective action.

Nakkanti says that she and her peers are uninterested in the larger political dimensions surrounding the book bans, whether it’s identity politics or political agendas. But as the country’s divided views on politics translate into local politics, students like her are finding ways to lend support, both emotional and tactical, to one another.

At the beginning of 2022, book bans started picking up momentum across the country. Even though debates over explicit content in schools are nothing new, The New York Times reported that this year they became increasingly politicized. Missouri’s Senate Bill 775 went into effect in late August, joining a group of five other states—Florida, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, and Utah—that influence what books can be shelved in school libraries. The new Missouri law says that providing “explicit sexual material to a student” is a Class A misdemeanor, which may result in a fine of up to $2,000 or jail time of up to one year. The ACLU is now involved and told the Nixa school district in May that it wanted all evidence preserved while it considered litigation. A spokesperson for ACLU Missouri told Defector that their status remained the same on the issue.

This traps kids like the Nixa students amidst political theater designed to provoke extreme and polarizing views, rather than discussions about what is supposedly at the heart of many of these laws: the well-being of children and teens. In Nixa, this all came to a head during one school board meeting in May.

Typical school board meetings are sparsely attended, Nakkanti said. But the night when she and her fellow students went to make their case to stop the school board from banning several book titles, it was in front of a much larger crowd than usual. It included local journalists, and “all these random people who showed up.”

Thomasina Brown, 16, a junior at Nixa High who was texting with Nakkanti about the bans, also attended the meeting. It was clear to her that the issue was having the freedom to read what you want. But there was much more happening that night.

“At the meeting, a lot of the people going up there would say that Nixa is a conservative town, and we're trying to keep it that way, and things like that,” Brown said. “But I really don't think it should be politicized in that way. Because it's really just about each individual person having their own right to read the content that they choose.”

The students had thoroughly researched the books in question before they came to the meeting. They had spoken to more than 340 Nixa students who were also opposed to the restrictions, studied lawsuits involving similar bans, and put together a petition that garnered hundreds signatures in about a week. They had read and studied several of the books that adults wanted to remove from libraries and noted that in many of the books only a fraction of the pages—13 out of 320 pages in Homegoing, and only four pages in Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home—contained the kind of content that the adults seemed concerned about. When the time came, the students spoke about how they related to the characters in the books and how the themes in these books helped them “find who we are, and can allow us to better understand others’ ideas and perspectives,” one student wrote in a speech, a copy of which they provided to Defector.

Brown said she was disappointed by how many parents said they were intent on protecting children while simultaneously dismissing what the students had to say. She recalled standing in the back of the room, next to the adults who were in favor of the book bans, overhearing every disparaging word.

“It was really difficult to hear all the snide remarks they would make about my classmates getting up and speaking,” Brown said. “Hearing the parents, and the members of the community kind of demean them for that was really disheartening.”

At one meeting, public comment went on for more than two hours. One person suggested that teachers were “peddling radical gender theory and Critical Race Theory," according to the Springfield News-Leader. Some parents bemoaned the need to preserve the innocence of children while others saw the ban as a slippery slope to fascism, the News-Leader reported. Several supporters of the book bans pushed for harsher punishments for distributing books with explicit content, with attendees suggesting jail time for librarians and school officials for exposing children and teens to explicit content. There even were discussions about putting school librarians on national registries.

"If the four Nixa employees on this committee voted to keep these books on the shelves, you belong on a national registry … I'd like to call for the resignation of the Nixa High School librarian," parent Carissa Corson said, per the News-Leader.

“It was, of course, horrifying to hear these things," Nakkanti said. "But we had to remember to kind of ground ourselves and realize that not only is it not the most prevalent opinion [...]. And we were just going to ignore those ridiculous arguments. We were going to focus on the core of the issue, which is student access to books and that we should always have that access.”

At the end of September, Nixa High School announced in an email to parents that it had restricted access to a total of 10 books, including Homegoing and Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye. In addition, two books were taken off the shelves entirely: Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home and George Matthew Johnson’s All Boys Aren't Blue: A Memoir-Manifesto.

“I'm terrified of the number [of banned books] increasing,” 17-year-old student Alex Rapp told Defector. “There's just so many when you think of like classics [that] can be threatened by the umbrella term 'sexually explicit content.'”

Incensed by that May school board meeting, Rapp has begun mobilizing more students. Alongside Nakkanti and Brown, Rapp keeps an eye on upcoming school board meetings and is trying to rally the student body to attend, though he has noticed many of his peers are discouraged by the latest announcement restricting access to more books. One promising sign, though: Rapp, now a senior, was heartened by the number of freshmen joining the protest against the book ban.

They’re not alone. Students at Nixa High are now increasingly informed by a national network of teen activists. Nakkanti joined the Intellectual Freedom Teen Council, a group of teenagers from across the country who are working to protect access to books in their home states. The program is run through the Brooklyn Public Library’s Books Unbanned program, which allows children and young adults from the ages of 13 to 21 to register for a digital Brooklyn Library card and check out ebooks. In the first five months after Books Unbanned was launched, the Brooklyn Library issued roughly 5,500 library cards to young folks across the country.

Nick Higgins, chief librarian at the Brooklyn Public Library, said the program began after he heard from a colleague in early 2022 about a list of 850 books that a Texas lawmaker was looking to remove from the state's schools. Higgins said that the response to the program was overwhelming. The library received “thousands and thousands” of requests for digital library cards, with most folks signing up from all 50 states and teens checking out roughly 8,900 books every month.

“We got inundated with all these requests," Higgins said. “It's great that we can provide this service for people and the support team, but also really heartbreaking that there are a lot of kids out there who don't have the community support around them to make sure that the books that they want to read are on the shelves.”

The demand also meant the initiative morphed from its simple beginnings into a platform for young people to organize with their peers across the country, in states where books are disappearing from the shelves of local libraries. According to Higgins, the teens who were working with the library on the Books Unbanned program started meeting with other teens whom they found through the program. Those conversations about the impact of book bans led to the creation of the Intellectual Freedom Teen Council, which meets monthly over Zoom.

Teens from Oklahoma to New York and back to Missouri have joined the council to exchange stories about successfully reinstating books, as well as the struggle to win back banned titles. And as Nakkanti’s network grew, she reached out to other teens across the country, including the Vandegrift High School Banned Book Club (or VHS Banned Book Club) in Austin, Texas, which has been running a book club around banned books since last fall and has provided information for others looking to organize their own book club.

“Hearing how other students are fighting this issue has been a great opportunity for us to share what we've learned, and also learn from other people,” Ella Scott, one of the cofounders of the VHS Banned Book Club, said in an email to Defector. “As students, it can be challenging to fight for change in a conversation that seems to revolve around adults. Through connecting with other students we've been able to empower each [other] through our fight for our right to read.”

The teens are now trying to find ways to distill their knowledge into tangible lessons to help others. One thing that seems to have worked in several districts is to see whether the parents have actually followed all the proper steps to get a book banned in accordance with local policies. Several students were able to reinstate access to specific books when they noted that adults had “messed up” during the submission process, Nakkanti said.

They are also trying to galvanize the information about local bans into a centralized place to give other students a leg up on this kind of research. Nakkanti hopes that these kinds of materials will help other students not feel “as alone or as confused or as lost [...] in this process.”

When many of the teens involved in these networks first heard of the book bans, they were often caught off guard and unaware that many efforts to bar access from books had been underway for months. Organizing has been a way of reclaiming agency in a conversation around book bans from which they have been largely excluded and they hope to keep growing their networks and sharing their knowledge. They want other teens to replicate their efforts and feel less isolated as they take on the challenge of keeping access to library books.

“That's been really cool," Nakkanti said, "to see how small change can ripple into something much larger."