Excerpted from Weird Moments in Cleveland Sports: Bottlegate, Bedbugs, and Burying the Pennant, by Vince Guerrieri. The book is available now; buy it here.

Certain players are closely, even automatically, associated with Cleveland sports. Others were part of Cleveland at one time, although their greatest successes came elsewhere. They were here early in their careers and moved on for greener pastures, or made a stop at or near the end of the line, when their names exceeded their talents.

In the 1990s, as the Indians put together the dynasty that almost was, winning five straight division titles and making two World Series appearances, the team sought that one missing piece that would put them over the top. And that led to some interesting acquisitions.

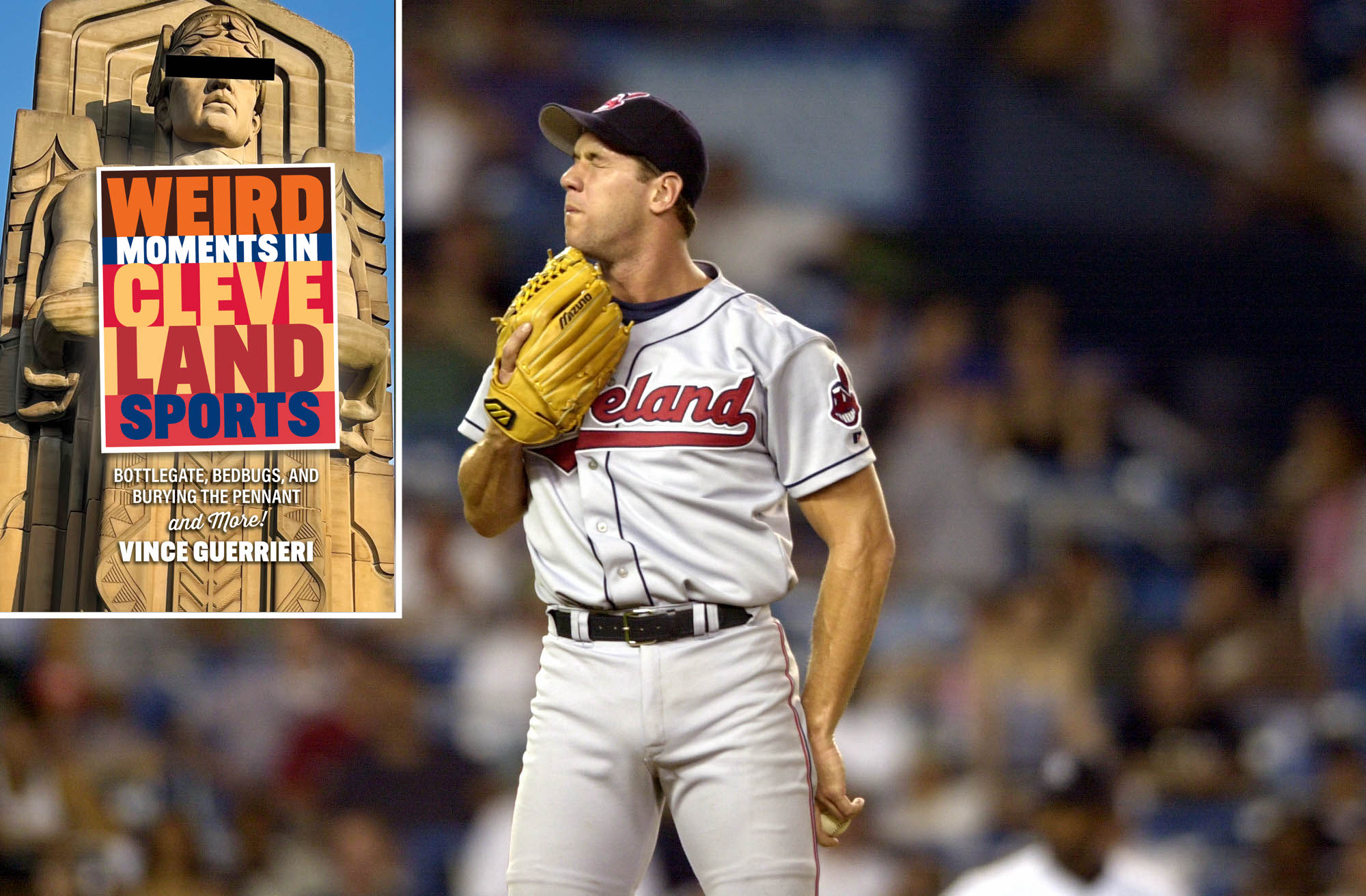

Jack Morris

As the Indians moved into the new baseball-only ballpark at the corner of Carnegie and Ontario, the farm system stocked by Hank Peters and John Hart started to bear fruit. Draft picks Albert Belle, Charles Nagy, Jim Thome, and Manny Ramirez were becoming productive regular players, and the Indians were making shrewd deals, yielding Kenny Lofton, Carlos Baerga, Sandy Alomar Jr. and Omar Vizquel in trades.

Among the new faces on the Indians’ roster when they took the field for the first time at Jacobs Field in 1994 was an old hand skilled at winning, with four World Series rings.

Jack Morris was one of the most dominant pitchers in Major League Baseball—and a noted Tribe-killer, going 31-12 against mostly moribund Indians teams. In the 1980s, Morris led all MLB pitchers with 162 wins. He was the ace of the Detroit Tigers’ staff when they led wire to wire on the way to winning the 1984 World Series.

In 1991, he signed with his hometown Minnesota Twins, and was a vital part of their world championship that year, starting—and finishing—a 10-inning Game 7. From there, he signed a massive free-agent contract in Toronto, using some of the proceeds to buy 7,000 acres in Great Falls, Montana, and leasing another 3,000 for a wheat farm. It would turn out to be a fateful move.

Morris led the majors with 21 wins in 1992, as the Blue Jays won the first of what turned out to be back-to-back World Series. His postseason was less than stellar, going 0-3. After going 7-12 in 1993, Morris wasn’t part of the postseason roster, and following the season, the Blue Jays bought out his contract. “In my heart and mind I wasn’t content walking away under those conditions,” he told the Los Angeles Times the following year, while he was in spring training with the Indians after signing a low-risk, incentive-laden one-year “prove it” deal.

“I think they can win the World Series,” Morris said after the Indians signed him. “When I left Detroit after 1990, I knew Minnesota was going to win the World Series in 1991. When I left Minnesota, I knew Toronto would win the World Series and they’ve won two straight. So when I say that, you should listen.”

Recovering from elbow problems, Morris made $350,000 just for making the Indians’ Opening Day roster. He was scheduled to start the second regular-season game at Jacobs Field—but it got snowed out, postponing his Indians debut to the next day. He got the win, then struggled for the next month, going 0-3 in his ensuing four starts. The skid inspired him to shave his trademark mustache, noting that his fortunes had reversed after doing so in 1991.

And it seemed to work, as Morris won four straight starts, including his 250th career win. Then, it started to appear that his mind was elsewhere—specifically, Great Falls, Montana, where his farm was. He would make his scheduled start and then leave for Montana to attend to matters there. He was also dealing with personal issues. An engagement was called off, and teammates claimed to have seen him in tears in the Indians dugout.

The last straw came Aug. 7, when the Indians played the Red Sox in a doubleheader at Fenway Park. The Tribe desperately needed to keep pace with the White Sox, who were leading the American League Central. They lost the first game. Morris started the second game (which was also Albert Belle’s first game back following his suspension for the corked bat incident in Chicago) and let a 5-0 lead slip away. He was lifted in the fourth with a 5-4 lead and the bases loaded. “It’s crunch time on the farm,” he told manager Mike Hargrove, according to the Plain Dealer postmortem on Morris’s time in Cleveland. “It’s crunch time here, too!” Grover retorted.

The next batter, Tim Naehring, tied the game with a chopper over Jim Thome’s head at third base.

Ultimately, the Indians rallied in 12 innings for the win, 15-10. By the time they did, Morris was gone from the clubhouse, on a plane to Montana. “That’s when we decided to cut the cord,” Hargrove said. Two days later—with a players’ strike looming—the team announced Morris’ release. He’d gone 10-6 for the Indians, who were the American League wild card team, just a game out of first in the Central, when the season ended just as abruptly as Morris’ time in Cleveland earlier that week.

Morris attended spring training the following year for the Reds, but never made it to the big-league roster. His career—which was enough to eventually take him to the Hall of Fame—was over. It wasn’t as ignominious an end as it would have been if he’d hung it up after the Blue Jays bought him out, but it ended on a sour note. Indians General Manager John Hart said after his release, “He can go back to doing whatever one does on a ranch.”

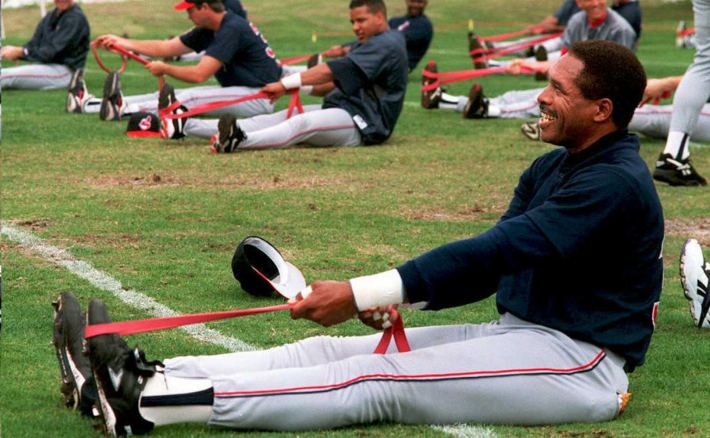

Dave Winfield

As the 1994 season wore on, the Indians felt they needed reinforcements and turned to another aging star who felt like he still had a little left.

Dave Winfield was one of the preeminent athletes of the 1970s. He’d been drafted as a high schooler by the Orioles, but opted to attend the University of Minnesota, where he played baseball and basketball. He was drafted by the Atlanta Hawks of the NBA and the Utah Stars of the ABA, and although he’d never played football in high school or college, the Minnesota Vikings saw fit to spend a 17th round pick on Winfield. But the Padres picked him fourth overall, and Winfield signed with them—going to the major leagues without a day in the minors.

For all Winfield’s accomplishments, the postseason had eluded him for most of his career. He played for the Padres, who were so bad that owner Ray Kroc once screamed at them over the public address system at Jack Murphy Stadium. Following the 1980 season, Winfield signed a 10-year deal with the Yankees. He saw the playoffs in 1981, as the Yankees lost the World Series to the Dodgers, but a fallow period in the Bronx soon followed. Owner George Steinbrenner blamed Winfield, whom he called “Mr. May” for his early-season performance that would fade as the year went on. Ultimately, the desire to dig up dirt on Winfield led to Steinbrenner’s ban from baseball, and Winfield was only too happy to accept a trade to the Angels.

Southern California was good to him, as he earned AL Comeback Player of the Year in 1990. He finished out the 10-year contract in Anaheim and signed as a free agent with the Blue Jays, where he got what turned out to be his only World Series ring, in 1992. He then joined his hometown Twins, not far removed from a World Series win themselves.

Winfield was still with the Twins when play stopped on Aug. 12, 1994, for what turned out to be a lengthy players’ strike. But as long as there was a chance that there would be baseball that year, Indians GM John Hart continued to make moves, and he acquired Winfield—while he was technically on strike—just before midnight on Aug. 31, the deadline for rosters to be set for whatever postseason might be played.

“I don’t have any inside information that the strike is going to end,” Hart told the Plain Dealer the time, “but I couldn’t live with myself if we had a chance to improve and didn’t do something.”

Winfield waived a no-trade clause for the deal. Hart told the Plain Dealer that Winfield said, “I love your club and I think I can help.”

Because it was during the strike, there was some confusion about terms for a guy who would be a free agent at the end of the 1994 season (an end that nobody yet realized had already happened: baseball wouldn’t resume until 1995). The deal between the Indians and Twins was Winfield for “future considerations,” a broader term than the cliched “player to be named later.” It has entered popular lore that Hart bought Twins general manager Andy MacPhail dinner to call it square, but the truth seems to be more nebulous than that.

At any rate, Winfield was re-signed as a free agent by the Indians for the 1995 season. His biggest moment with the Indians came on Memorial Day that year, when he hit a three-run home run in a game that saw the Tribe rally from six runs down to beat the White Sox and cement their claim as the new titans of the American League Central Division.

Winfield made two trips to the disabled list that year with a rotator cuff injury. To his chagrin, he was left off the postseason roster (the Indians instead added Ruben Amaro), but he remained a bench presence, rooting on his teammates. Following the season, he hung it up. He was diplomatic as he rode off into the sunset, with nothing but warm feelings of his time in Cleveland.

“I couldn’t think of a better group of guys to go out with,” he told the Plain Dealer’s Tony Grossi the following spring. “And a better city.”

Jack McDowell

Following the loss to the Braves in 1995 World Series, the Indians identified pitching as a priority for off-season acquisitions. Their rotation was led by Orel Hershiser and Dennis Martinez, both crafty veterans, but both with more of their career behind them than ahead of them. Charlie Nagy and Mark Clark were solid starters. Ken Hill was leaving via free agency.

A premium pitcher was needed. And the Indians went out and got one, signing Jack McDowell shortly before Christmas 1995—a present, owner Dick Jacobs said, for fans.

McDowell started his major league career with the White Sox, and was a mainstay of their rotation, winning the 1993 American League Cy Young Award. But after a strike-shortened 1994 season, he was dealt to the Yankees in a cost-cutting move.

He went 15-10 in his lone season in the Bronx, leading the league for the third time in complete games, with eight. But he earned the enmity of the Bleacher Creatures for giving fans a one-fingered salute after being pulled from the second game of a doubleheader in the fourth inning as he was being shelled. McDowell apologized after the game, saying he’d lost his composure, but the damage was done. The city’s tabloids called him “Jack the Flipper.” The Yankees made the playoffs for the first time in 14 years, but didn’t advance past the Division Series, as McDowell took the loss in Game 3 and gave up the tying and winning runs in the 11th inning of the deciding Game 5.

The Yankees didn’t offer McDowell arbitration, and the Indians signed him to a two-year, $10 million deal, with a club option for a third year. It was a major coup for the Indians. McDowell had 98 wins to that point in the 1990s, more than any other pitcher that decade. Known as “Black Jack,” a nickname bestowed on him by White Sox broadcaster (and former Indians player) Ken Harrelson, he brought an almost villainous intensity.

“When he was on the other team, you just didn’t like Jack on general principle,” Manager Mike Hargrove told the Plain Dealer in spring training. “It was nothing specific. It was because he beat the hell out of you. If you get your brains beat out by a guy enough, it gets personal.”

The one black mark against Black Jack was his postseason record: 0-4 in two series, in 1993 with the White Sox and 1995 with the Yankees.

McDowell went a respectable 13-9 in 1996, but he called it the most disappointing year of his career to that point. The normally durable pitcher went on the disabled list for the first time in his career with a strained right forearm, and he wasn’t the same pitcher when he returned.

Burdened by high expectations, the Indians won 99 games that year for their second straight division title, but it wasn’t the same. The clubhouse was more tense. The nucleus that had guided the team to the best record in the majors the year before was starting to peel off. Mark Clark was traded to the Mets before the season started. Carlos Baerga was also dealt to Queens. Eddie Murray was losing at-bats and was traded to his former team, the Orioles. Albert Belle had one foot out the door as his free agency loomed.

The Indians dropped two straight to start the American League Division Series, and McDowell suddenly found himself pitching to save the team’s season. It was the game they’d signed him for. He let the lead slip away thanks to a monstrous home run by B. J. Surhoff, and left a tie game in the sixth. The Indians rallied to win, but it only postponed the inevitable. They lost Game 4 to end the series and head off into a long, cold winter. (At least this time McDowell got a no-decision, instead of losses like he did in Chicago and New York.)

The following year, McDowell was moved to the bullpen early in the season—which didn’t sit well with him. Then, in May, he underwent arthroscopic surgery for bits of cartilage in his elbow. He was rehabbing his way back when he was found to have a bone bruise in his arm. The Indians, who appeared to be spinning their wheels in August, shut him down for the season. The team wouldn’t pick up his third-year option, bringing a quiet end to McDowell’s time in Cleveland. He didn’t lead the Indians to the Promised Land. He only got one postseason start, and went 16-12 in two underachieving, injury-plagued years in Cleveland. He hung on for two more years in Anaheim, but his time in Cleveland was really the beginning of the end for Black Jack McDowell.

“When you get a guy with Jack’s ability,” first baseman Jim Thome said in the Plain Dealer, “you naturally think that he could be the guy to take us over the top. It is sad and unfortunate that this had to happen.”

John Rocker

After Jose Mesa’s immolation in Game 7 of the 1997 World Series, the Indians cycled through several closers. Mike Jackson filled the role before leaving via free agency after the 1999 season. Then it was Steve Karsay, until at the trade deadline in 2000 the Indians dealt for Bob Wickman, a burly right-hander who attributed his sinker to the loss of a tip of his index finger in a childhood accident on the family farm.

In 2001, which was already slated to be his last year at the helm in Cleveland, General Manager John Hart had one more trick up his sleeve, trading Karsay—an impending free agent who was unhappy that he was no longer the closer—and Steve Reed to the Braves for controversial reliever John Rocker.

“With John Rocker we’re bringing in a devastating left-handed late reliever,” Hart said. “He’s 26. A dominant closer. A workhorse who has never been on the disabled list and he has great numbers in the regular season and the postseason.”

Rocker had 38 saves in 1999, and 24 more in 2000. Before the Indians acquired him, he was leading the National League in saves, with 19 in 23 opportunities for the Atlanta Braves. In more than 19 postseason innings, he had a 0.00 ERA.

But numbers tell only part of Rocker’s story. His intensity (which he later admitted was steroid-aided) bordered on being unhinged. At 6 feet, 4 inches tall and 225 pounds, he looked like “10 pounds of malevolence in a five-pound bag,” according to Plain Dealer columnist Bill Livingston. Rocker sprinted in from the bullpen for relief appearances. When fans heckled, he’d give it right back. And he had become notorious for a 1999 Sports Illustrated interview that had given full voice to racist, sexist, homophobic beliefs, famously denigrating riders of the New York City subway, talking about “some kid with purple hair next to some queer with AIDS right next to some dude who just got out of jail for the fourth time right next to some 20-year-old mom with kids.”

As a result, Rocker was suspended and fined by Major League Baseball, an unprecedented punishment for the high crime of giving an interview to one of the most prominent and popular outlets in sports journalism.

Rocker had rubbed some teammates the wrong way too. The Sports Illustrated interview included him referring to teammate Randall Simon as a “fat monkey.” When Chipper Jones expressed relief at Rocker’s trade from Atlanta, the reliever called him “white trash.” But his new Indians teammates, who were trying to get back on top of the American League Central Division after finishing second to the White Sox the year before, were willing to give him a chance—with one glaring exception.

Bob Wickman, on the verge of signing a long-term deal with the Indians, halted talks immediately. He would be OK with staying on the team for the remainder of the season as the playoffs loomed, but he, like Karsay, expected to be a closer, if not in Cleveland, then somewhere else.

It was a fraught marriage from the very start. Rocker joined the team in Kansas City, after enough flight delays and detours that he said, “I took the direct route through Oklahoma” in his introductory news conference. The Indians’ next stop on their road trip was the Bronx. A reporter asked about the possible reaction he might get from Yankees fans.

“Why is reaction such a big deal to you people?” he snapped. “Who cares about reaction? The mound is still 60 feet, 6 inches away from home plate. There’ll be a guy standing there with a 32-ounce bat. Who cares about reaction?”

Almost instantly, Rocker’s appearance turned into a distraction. A fan in Oakland threw a beer at him while he was in the bullpen. Another, in Seattle, was wearing all white and said, “Hey, John, we’ve got a KKK meeting tonight and we’d like you to attend.”

Rocker’s time with the Indians was brief but terrible. He went 3-7 with four saves—although he was the winning pitcher for the Indians on Aug. 5, in which they came back from 12 runs down to beat the Mariners 15-14 on Sunday Night Baseball. Soon enough, Wickman found himself the closer again.

The Indians won their division, but were fated to play the Mariners, who’d tied a major league record with 116 wins. (The Indians were by far the weakest of the division winners, winning 91 games. Even the wild card Athletics—who couldn’t play the Mariners in the first round, by rules in place at the time—had 102 wins.) Rocker made the postseason roster, but he was a non-factor on the field. In the clubhouse, on the other hand . . .

During Game 1, an Indians win, Rocker threw cups of water at heckling fans. Following Game 2, which was won by the Mariners to even the series, Rocker said, “There’s a certain guy on this team who has a lawsuit filed against him for gay bashing. Why doesn’t that make the papers?” The reference was to Wickman, who was being sued by a former clubhouse attendant at Yankee Stadium, who alleged that he was fired for being gay and HIV positive, and that Wickman, a Yankees pitcher at the time, had called him homophobic slurs and sexually harassed him. (The Yankees said the attendant was fired for stealing team equipment, and the lawsuit, which also named pitchers Mariano Rivera and Jeff Nelson, was eventually thrown out of court.)

After the season, Wickman was given a three-year contract—a sign of buyer’s remorse by the Indians, as well as the fact that they’d move on from Rocker as soon as they could. New Indians General Manager Mark Shapiro went to the winter meetings with the intention of unloading Rocker. He didn’t expect much back—he was what real estate agents would call a motivated seller—and nobody was sure he’d even find someone willing to take a chance on Rocker.

But there was one person: The same one who took a chance on him six months earlier. The Indians’ succession plan had been for Hart to serve as an advisor to Shapiro after stepping down as GM, but Rangers owner Tom Hicks, no doubt impressed with the Indians of the 1990s, hired Hart, making him the highest-paid general manager in the major leagues.

“It all goes back to second chances,” Hart said about his second trade for Rocker.

The Indians were going into rebuilding mode, and wouldn’t win the division again for six years. Rocker made 30 appearances for the Rangers in 2002 before being released at the end of the season. He made two more appearances for Tampa the following year, and that was the end of his major league career. He’s since written for far-right website WorldNetDaily and appeared on the TV show Survivor.

From Weird Moments in Cleveland Sports: Bottlegate, Bedbugs, and Burying the Pennant by Vince Guerrieri. Reprinted by permission of Gray & Company. The book is available now; buy it here.